| |||||||||||||||||

1585 provincial seats contested | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

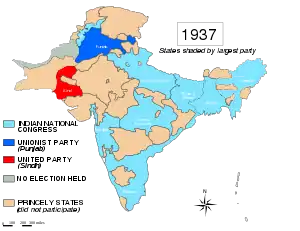

Provincial elections were held in British India in the winter of 1936-37 as mandated by the Government of India Act 1935. Elections were held in eleven provinces - Madras, Central Provinces, Bihar, Orissa, the United Provinces, the Bombay Presidency, Assam, the North-West Frontier Province, Bengal, Punjab and Sind.

The final results of the elections were declared in February 1937. The Indian National Congress emerged in power in seven of the provinces, Bombay, Madras, the Central Provinces, the United Provinces, the North-West Frontier Province, Bihar, and Orissa. The exceptions were Bengal, where the Congress was nevertheless the largest party, Punjab, Sindh, and Assam. The All-India Muslim League failed to form the government in any province.

The Congress ministries resigned in October and November 1939, in protest against Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's action of declaring India to be a belligerent in the Second World War without consulting the elected representatives of the Indian peoples.

Electorate

The Government of India Act 1935 increased the number of enfranchised people.[1][2] Approximately 30 million people, among them some women, gained voting rights. This number constituted one-sixth of Indian adults. The Act provided for a limited adult franchise based on property qualifications such as land ownership and rent, and therefore favored landholders and richer farmers in rural areas.[2]

Election Campaign

At its 1936 session held in the city of Lucknow, the Congress party, despite opposition from the newly elected Nehru as the party president, agreed to contest the provincial elections to be held in 1937.[3][4] The released Congress leaders anticipated the restoration of elections. They now had a stronger standing with their reputation enhanced by the civil disobedience movement under Gandhi's leadership.[5] Through the elections the Congress sought to convert its popular movement into a political organisation. The Congress won 758 out of around 1500 seats in a resounding victory, and went on to form seven provincial governments. The Congress formed governments in United provinces, Bihar, the Central Provinces, Bombay and Madras.[6]

The party's election platform had downplayed communalism and Nehru continued this attitude with the initiation of the March 1937 Muslim mass contact program. But the elections demonstrated that of the 482 Muslim seats the Congress had contested just 58 of them and won only 26 of those. In spite of this poor showing the Congress persisted in its claim that the party was representative of all communities.[1] The Congress ministries did not succeed in attracting their Muslim countrymen. This was largely unintentional.[7]

Results

The 1937 elections demonstrated that neither the Muslim League nor the Congress represented Muslims. It also demonstrated the provincial moorings of Muslim politics.[8] The Muslim League captured around 25 percent of the seats reserved for Muslims. The Congress Muslims achieved 6 percent of them. Most of the Muslim seats were won by regional Muslim parties.[9] No Congress Muslim won in Sindh, Punjab, Bengal, Orissa, United Provinces, Central Provinces, Bombay and Assam.[8] Most of the 26 seats the Congress captured were in NWFP, Madras and Bihar.[10]

Legislative Assemblies

| Province | Congress | Muslim League | Other parties | Independents | Muslim seats | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assam | 33 | 10 | 24 (Assam Valley Party) 14 (Non-Congress) | 27 | 34 | 108 |

| Bengal | 54 | 43[11] | 36 (Krishak Praja Party) 10 (Independent Muslims) | 113 | 119 | 250 |

| Bihar | 98 | 0 | 20 (Muslim Independent Party) 05 (Muslim United Party) 03 (Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam) | 32 | 34 | 152 |

| Bombay | 86 | 18 | 14 (Ambedkarites) 9 (Non-Brahmin) 4 (Other) 2 (Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam) | 42 | 30 | 175 |

| Central Provinces | 70 | 5 | 8 (Muslim Parliamentary Board) 8 (Other) | 21 | 112 | |

| Madras | 159 | 9 | 21 (Justice Party) | 26 | 29 | 215 |

| North West Frontier Province | 19 | 0 | 7 (Hindu-Sikh Nationalists) | 24 | 36 | 50 |

| Orissa | 36 | 0 | 14 | 10 | 60 | |

| Punjab | 18 | 2 | 95 (Unionist Party) 14 (Khalsa National Board) 11 (Hindu Election Board) 10 (Akalis) 4 (Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam) | 22 | 86 | 175 |

| Sind | 7 | 0 | 17 (United Party) 16 (Party of Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah) 12 (Hindu) 3 (Europeans) | 5 | 34 | 60 |

| United Provinces | 133 | 29[12] | 22 (National Agriculturists) | 47 | 66 | 228 |

| Total | 707 | 116 | 397 | 385 | 1585 |

Legislative Councils

| Province | Congress | Muslim League | Other parties | Independents | Europeans | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assam | 10 (Non-Congress) 6 (Assam Valley Muslim Party) | 2 | 3 | 21 | ||

| Bengal | 9 | 7 | 9 (Krishak Praja Party) | 32 | 6 | 63 |

| Bihar | 8 | 2 (United) | 16 | 3 | 29 | |

| Bombay | 13 | 2 | 2 (Democratic Swaraj) 1 (Majlis-e-Ahrar) | 8 | 4 | 30 |

| Madras | 26 | 3 | 5 (Justice Party) | 12 | 8 | 54 |

| United Provinces | 8 | 4 (National Agriculturists) 1 (Majlis-e-Ahrar) | 39 | 8 | 60 | |

| Total | 64 | 12 | 38 | 111 | 32 | 257 |

Madras Presidency

In Madras, the Congress won 74% of all seats, eclipsing the incumbent Justice Party (21 seats).[13]

Sindh

The Sind Legislative Assembly had 60 members. The Sind United Party emerged the leader with 22 seats, and the Congress secured 8 seats. Mohammad Ali Jinnah had tried to set up a League Parliamentary Board in Sindh in 1936, but he failed, though 72% of the population was Muslim.[14] Though 34 seats were reserved for Muslims, the Muslim League could secure none of them.[15]

United Provinces

The UP legislature consisted of a Legislative Council of 52 elected and 6 or 8 nominated members and a Legislative Assembly of 228 elected members: some from exclusive Muslim constituencies, some from "General" constituencies, and some "Special" constituencies.[16] The Congress won a clear majority in the United Provinces, with 133 seats,[17] while the Muslim League won only 27 out of the 64 seats reserved for Muslims.[18]

The Congress refused to form coalition with the League, even though two parties had a verbal understanding to do so.[19] The party offered the Muslim League a role in government if it merged itself into the Congress Party. While this position had a good basis it proved to be a mistake.[1] The Congress disregarded that even though they had captured the large part of UP's general seats, they had not won any of the reserved Muslim seats, of which the Muslim League had won 29.[20]

Assam

In Assam, the Congress won 33 seats out of a total of 108 making it the single largest party, though it was not in a position to form a ministry. The Governor called upon Sir Muhammad Sadulla, ex-Judicial Member of Assam and Leader of the Assam Valley Muslim Party to form the ministry.[21] The Congress was a part of the ruling coalition.

Bombay

In Bombay, the Congress fell just short of gaining half the seats. However, it was able to draw on the support of some small pro-Congress groups to form a working majority. B.G. Kher became the first Chief Minister of Bombay.

Punjab

After result Unionist Party under the leadership of Sikandar Hayat Khan formed the Government. Khalsa National Board and Hindu Election Board also gave their support to Unionist Party.

Sikandar Hayat Khan led a coalition government till his death. After his death he was succeeded by Malik Khizar Hayat Tiwana on 12 December 1942.

Bengal

In Bengal, although the Congress was the single largest party, with 54 seats, it was unable to form a government. The Krishak Praja Party of Prime Minister A. K. Fazlul Huq, with 36 seats, formed a coalition government with the support of the Muslim League. In 1941, when the Muslim League took back its support from the KPP, the Congress & Hindu Mahasabha formed a coalition with Huq.[22]

Other provinces

In three additional provinces, Central Provinces, Bihar, and Orissa, the Congress won clear majorities. In the overwhelmingly Muslim North-West Frontier Province, Congress won 19 out of 50 seats and was able, with minor party support, to form a ministry.[23]

Muslim League

Jinnah took a nationalist stance and emulated the Congress' electoral campaign and appointed Muslim League Parliamentary Boards for the 1937 elections. Through this he expected to advance the party as a coalition partner for the Congress which they might need to form provincial governments. He miscalculated that the separate electorates system, with a larger electorate, would produce good results for the Muslim League.[24] Of the 482 seats reserved for Muslims the League won just 109. The League won 29 seats in the United Provinces where it had competed for 35 out of the 66 seats for Muslims.[8] The League's top performance was in provinces where Muslims were minorities; there it cast itself as a protector of the community.[1] Its performance in Punjab, where it won just two of the seven seats it vied for, was unsuccessful. It performed a little better in Bengal, capturing 39 of the 117 seats for Muslims, but could not form a government.[8]

Muslim preference was to be represented by regional parties which were allied with those non-Muslims who were not supportive of the Congress.[25] The Congress was victorious throughout India in the open constituencies. Muslim league was confronted with the fact that Hindu majority provinces would be ruled by Hindus but Muslim league would not rule the largest provinces with Muslim majorities: Bengal and Punjab. The Congress domination over the government made the prospects of federal Muslim politicians appear dismal.[25] Regional parties kept the League out of power in those provinces with Muslim majorities while in the Hindu majority provinces it was unwanted by the Congress.[26] Antagonised by this rebuff the League stepped up its efforts to attract a popular following.[27]

Resignation of Congress ministries

On 3 September 1939, Viceroy of India Lord Linlithgow declared India to be at war with Germany alongside Britain.[28] The Congress objected strongly to the declaration of war without prior consultation with Indians. The Congress Working Committee suggested that it would cooperate if a central Indian national government were formed and a commitment were made to India's independence after the war.[29] The Muslim League promised its support to the British,[30] with Jinnah calling on Muslims to help the Empire by "honourable co-operation" at the "critical and difficult juncture," while asking the Viceroy for increased protection for Muslims.[31]

The government did not come up with any satisfactory response. Viceroy Linlithgow could only offer to form a 'consultative committee' for advisory functions. Thus, Linlithgow refused the demands of the Congress. On 22 October 1939, all Congress ministries were called upon to tender their resignations. Both Viceroy Linlithgow and Muhammad Ali Jinnah were pleased with the resignations.[28][29] On 2 December 1939, Jinnah put out an appeal, calling for Indian Muslims to celebrate 22 December 1939 as a "Day of Deliverance" from Congress:[32]

I wish the Musalmans all over India to observe Friday 22 December as the "Day of Deliverance" and thanksgiving as a mark of relief that the Congress regime has at last ceased to function. I hope that the provincial, district and primary Muslim Leagues all over India will hold public meetings and pass the resolution with such modification as they may be advised, and after Jumma prayers offer prayers by way of thanksgiving for being delivered from the unjust Congress regime.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Ian Talbot; Gurharpal Singh (23 July 2009). The Partition of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-521-85661-4.

- 1 2 Low, David Anthony (1993). Eclipse of empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-521-45754-8.

- ↑ B. R. Tomlinson (18 June 1976). The Indian National Congress and the Raj, 1929–1942: The Penultimate Phase. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 57–60. ISBN 978-1-349-02873-3.

- ↑ Thakur, Pradeep. The Most Important People of the 20th Century (Part-I): Leaders & Revolutionaries. Lulu.com. ISBN 9780557778867.

- ↑ Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 195.

- ↑ Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 196.

- ↑ Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 196.

- 1 2 3 4 Hardy; Thomas Hardy (7 December 1972). The Muslims of British India. CUP Archive. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-521-09783-3.

- ↑ Hermanne Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund. A History of India (PDF) (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Hardy; Thomas Hardy (7 December 1972). The Muslims of British India. CUP Archive. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-0-521-09783-3.

- ↑ Jalal, Ayesha (18 April 1985). The Sole Spokesman. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511558856. ISBN 978-0-521-24462-6.

- ↑ Dhulipala Venkat (28 July 2016). Creating a new Medina : state power, Islam, and the quest for Pakistan in late colonial North India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-61537-9. OCLC 968341808.

- ↑ Joseph E. Schwartzberg. "Schwartzberg Atlas". A Historical Atlas of South Asia. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ Jalal, Ayesha (1994). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- ↑ Afzal, Nasreen. Role of Sir Abdullah Haroon in Politics of Sindh (1872–1942) Archived 4 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine pp. 185

- ↑ Reeves, P. D. (1971). "Changing Patterns of Political Alignment in the General Elections to the United Provinces Legislative Assembly, 1937 and 1946". Modern Asian Studies. 5 (2): 111–142. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00002973. JSTOR 312028. S2CID 145663295.

- ↑ Visalakshi Menon. "From movement to government: the Congress in the United Provinces, 1937-42", Sage Publications, 2003. pp 60

- ↑ Abida Shakoor. "Congress-Muslim League tussle 1937-40: a critical analysis", Aakar Books, 2003, pp 90

- ↑ Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 196.

- ↑ Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 196–197.

- ↑ "Ministry-making in Assam". The Indian Express. 13 March 1937.

- ↑ Jalal, Ayesha (1994). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- ↑ Schwartzberg Atlas - Digital South Asia Library. Dsal.uchicago.edu. Retrieved on 2013-12-06.

- ↑ Hermanne Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund. A History of India (PDF) (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2015.

- 1 2 Hardy; Thomas Hardy (7 December 1972). The Muslims of British India. CUP Archive. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-521-09783-3.

- ↑ Hermanne Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund. A History of India (PDF) (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 197.

- 1 2 Anderson, Ken. "Gandhi - The Great Soul". The British Empire: Fall of the Empire. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- 1 2 Bandyopadhyay, Sekhara (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. India: Orient Longman. p. 412. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

- ↑ Schofield, Victoria (2003). Afghan Frontier: Feuding and Fighting in Central Asia. London, New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 232–233. ISBN 1860648959. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ↑ Wolpert, Stanley (22 March 1998). "Lecture by Prof. Stanley Wolpert: Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah's Legacy to Pakistan". Jinnah of Pakistan. Humsafar.info. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ↑ Nazaria-e-Pakistan Foundation. "Appeal for the observance of Deliverance Day, issued from Bombay, on 2nd December, 1939". Quaid-i-Azam’s Speeches & Messages to Muslim Students. Archived from the original on 29 July 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2007.