_Logo.png.webp) | |

| Country/ies of origin | |

|---|---|

| Operator(s) | ISRO |

| Type | Military, Commercial |

| Status | Operational |

| Coverage | Regional (up to 1,500 km or 930 mi from borders) |

| Accuracy | 3 m or 9.8 ft (public) 2 m or 6 ft 7 in (encrypted) |

| Constellation size | |

| Nominal satellites | 5 |

| Current usable satellites | |

| First launch | 1 July 2013 |

| Last launch | 29 May 2023 |

| Total launches | 10 |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Regime(s) | geostationary orbit (GEO), inclined geosynchronous orbit (IGSO) |

| Orbital height | 35,786 km (22,236 mi) |

| Other details | |

| Cost | ₹2,246 crore (US$281 million) as of March 2017[1] |

| Geodesy |

|---|

|

The Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System (IRNSS), with an operational name of NavIC (acronym for Navigation with Indian Constellation; also, nāvik 'sailor' or 'navigator' in Indian languages),[2] is an autonomous regional satellite navigation system that provides accurate real-time positioning and timing services.[3] It covers India and a region extending 1,500 km (930 mi) around it, with plans for further extension. An extended service area lies between the primary service area and a rectangle area enclosed by the 30th parallel south to the 50th parallel north and the 30th meridian east to the 130th meridian east, 1,500–6,000 km (930–3,730 mi) beyond borders where some of the NavIC satellites are visible but the position is not always computable with assured accuracy.[4] The system currently consists of a constellation of eight [5] satellites,[6][7] with two additional satellites on ground as stand-by.[8]

The constellation is in orbit as of 2018.[9][10][11][12] NavIC will provide two levels of service, the "standard positioning service", which will be open for civilian use, and a "restricted service" (an encrypted one) for authorised users (including the military).

NavIC-based trackers are compulsory on commercial vehicles in India[13][14] and some consumer mobile phones with support for it have been available since the first half of 2020.[15][16][17][18][19]

There are plans to expand the NavIC system by increasing its constellation size from 7 to 11.[20]

Background

The system was developed partly because access to foreign government-controlled global navigation satellite systems is not guaranteed in hostile situations, as happened to the Indian military in 1999 when the United States denied an Indian request for Global Positioning System (GPS) data for the Kargil region, which would have provided vital information.[21] The Indian government approved the project in May 2006.[22]

Development

Description

As part of the project, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) opened a new satellite navigation centre within the campus of ISRO Deep Space Network (DSN) at Byalalu, in Karnataka on 28 May 2013.[23] A network of 21 ranging stations located across the country will provide data for the orbital determination of the satellites and monitoring of the navigation signal.

A goal of complete Indian control has been stated, with the space segment, ground segment and user receivers all being built in India. Its location in low latitudes facilitates coverage with low-inclination satellites. Three satellites will be in geostationary orbit over the Indian Ocean. Missile targeting could be an important military application for the constellation.[24]

The total cost of the project was expected to be ₹14.2 billion (US$178 million), with the cost of the ground segment being ₹3 billion (US$38 million), each satellite costing ₹1.5 billion (US$19 million) and the PSLV-XL version rocket costing around ₹1.3 billion (US$16 million). The planned seven rockets would have involved an outlay of around ₹9.1 billion (US$114 million).[8][25][26]

The necessity for two replacement satellites, and PSLV-XL launches, has altered the original budget, with the Comptroller and Auditor General of India reporting costs (as of March 2017) of ₹22.46 billion (US$281 million).[1]

The NavIC Signal in Space ICD was released for evaluation in September 2014.[27]

From 1 April 2019, use of AIS 140 compliant NavIC-based vehicle tracking systems were made compulsory for all commercial vehicles in India.[13][14]

In 2020, Qualcomm launched four Snapdragon 4G chipsets and one 5G chipset with support for NavIC.[28][29] NavIC is planned to be available for civilian use in mobile devices, after Qualcomm and ISRO signed an agreement.[15][30] To increase compatibility with existing hardware, ISRO will add L1 band support. For strategic application, Long Code support is also coming.[31][32]

As per National Defense Authorization Act 2020, United States Secretary of Defense in consultation with Director of National Intelligence designated NavIC, Galileo and QZSS as allied navigational satellite systems.[33]

Time-frame

In April 2010, it was reported that India plans to start launching satellites by the end of 2011, at a rate of one satellite every six months. This would have made NavIC functional by 2015. But the program was delayed,[34] and India also launched 3 new satellites to supplement this.[35]

Seven satellites with the prefix "IRNSS-1" will constitute the space segment of the IRNSS. IRNSS-1A, the first of the seven satellites, was launched on 1 July 2013.[36][37] IRNSS-1B was launched on 4 April 2014 on-board PSLV-C24 rocket. The satellite has been placed in geosynchronous orbit.[38] IRNSS-1C was launched on 16 October 2014,[39] IRNSS-1D on 28 March 2015,[40] IRNSS-1E on 20 January 2016,[41] IRNSS-1F on 10 March 2016 and IRNSS-1G was launched on 28 April 2016.[42]

The eighth satellite, IRNSS-1H, which was meant to replace IRNSS-1A, failed to deploy on 31 August 2017 as the heat shields failed to separate from the 4th stage of the rocket.[43] IRNSS-1I was launched on 12 April 2018 to replace it.[44][45]

System description

The IRNSS system comprises a space segment and a support ground segment.

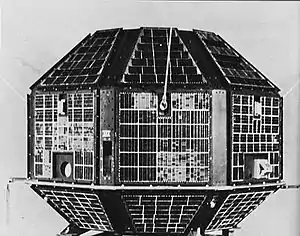

Space segment

The constellation consists of 7 satellites. Three of the seven satellites are located in geostationary orbit (GEO) at longitudes 32.5° E, 83° E, and 131.5° E, approximately 36,000 km (22,000 mi) above Earth's surface. The remaining four satellites are in inclined geosynchronous orbit (GSO). Two of them cross the equator at 55° E and two at 111.75° E.[46][47][48]

Ground segment

The ground segment is responsible for the maintenance and operation of the IRNSS constellation. The ground segment comprises:[46]

- IRNSS Spacecraft Control Facility (IRSCF)

- ISRO Navigation Centre (INC)

- IRNSS Range and Integrity Monitoring Stations (IRIMS)

- IRNSS Network Timing Centre (IRNWT)

- IRNSS CDMA Ranging Stations (IRCDR)

- Laser Ranging Stations

- IRNSS Data Communication Network (IRDCN)

The IRSCF is operational at Master Control Facility (MCF), Hassan and Bhopal. The MCF uplinks navigation data and is used for tracking, telemetry and command functions.[49] Seven 7.2-metre (24 ft) FCA and two 11-metre (36 ft) FMA of IRSCF are currently operational for LEOP and on-orbit phases of IRNSS satellites.[46][50]

The INC established at Byalalu performs remote operations and data collection with all the ground stations. The ISRO Navigation Centers (INC) are operational at Byalalu, Bengaluru and Lucknow. INC1 (Byalalu) and INC2 (Lucknow) together provide seamless operations with redundancy.[51]

16 IRIMS are currently operational and are supporting IRNSS operations[52] few more are planned in Brunei, Indonesia, Australia, Russia, France and Japan.[53] CDMA ranging is being carried out by the four IRCDR stations on regular basis for all the IRNSS satellites. The IRNWT has been established and is providing IRNSS system time with an accuracy of 2 ns (2.0×10−9 s) (2 sigma) with respect to UTC. Laser ranging is being carried out with the support of ILRS stations around the world. Navigation software is operational at INC since 1 Aug 2013. All the navigation parameters, such as satellite ephemeris, clock corrections, integrity parameters, and secondary parameters, such as iono-delay corrections, time offsets with respect to UTC and other GNSSes, almanac, text message, and earth orientation parameters, are generated and uploaded to the spacecraft automatically. The IRDCN has established terrestrial and VSAT links between the ground stations. As of March 2021, ISRO and JAXA are performing calibration and validation experiments for NavIC ground reference station in Japan.[54] ISRO is also under discussion with CNES for a NavIC ground reference station in France.[55] ISRO is planning a NavIC ground station at Cocos (Keeling) Islands and is in talks with the Australian Space Agency.[56]

Signal

NavIC signals will consist of a Standard Positioning Service and a Restricted Service. Both will be carried on L5 (1176.45 MHz) and S band (2492.028 MHz).[57] The SPS signal will be modulated by a 1 MHz BPSK signal. The Restricted Service will use BOC(5,2). The navigation signals themselves would be transmitted in the L5 (1176.45 MHz) & S band (2492.028 MHz) frequencies and broadcast through a phased array antenna to maintain required coverage and signal strength. The satellites would weigh approximately 1,330 kg (2,930 lb) and their solar panels generate 1,400 W.

A messaging interface is embedded in the NavIC system. This feature allows the command center to send warnings to a specific geographic area. For example, fishermen using the system can be warned about a cyclone.[58]

Accuracy

The Standard Positioning Service system is intended to provide an absolute position accuracy of about 5 to 10 metres throughout the Indian landmass and an accuracy of about 20 metres (66 ft) in the Indian Ocean as well as a region extending approximately 1,500 km (930 mi) around India.[59][60] GPS, for comparison, has a position accuracy of 5 m under ideal conditions.[61] However, unlike GPS, which is dependent only on L-band, NavIC has dual frequencies (S and L bands). When a low-frequency signal travels through atmosphere, its velocity changes due to atmospheric disturbances. GPS depends on an atmospheric model to assess frequency error, and it has to update this model from time to time to assess the exact error. In NavIC, the actual delay is assessed by measuring the difference in delay of the two frequencies (S and L bands). Therefore, NavIC is not dependent on any model to find the frequency error and can be more accurate than GPS.[62]

List of satellites

The constellation consists of 7 active satellites. Three of the seven satellites in constellation are located in geostationary orbit (GEO) and four are in inclined geosynchronous orbit (IGSO). All satellites launched or proposed for the system are as follows:

IRNSS series satellites

| Satellite | SVN | PRN | Int. Sat. ID | NORAD ID | Launch Date | Launch Vehicle | Orbit | Status | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRNSS-1A | I001 | I01 | 2013-034A | 39199 | 1 July 2013 | PSLV-XL-C22 | Geosynchronous (IGSO) / 55°E, 29° inclined orbit | Partial Failure | Atomic clocks failed.The satellite is being used for NavIC's short message broadcast service.[51][64][65] |

| IRNSS-1B | I002 | I02 | 2014-017A | 39635 | 4 April 2014 | PSLV-XL-C24 | Geosynchronous (IGSO) / 55°E, 29° inclined orbit | Operational | |

| IRNSS-1C | I003 | I03 | 2014-061A | 40269 | 16 October 2014 | PSLV-XL-C26 | Geostationary (GEO) / 83°E, 5° inclined orbit | Operational | |

| IRNSS-1D | I004 | I04 | 2015-018A | 40547 | 28 March 2015 | PSLV-XL-C27 | Geosynchronous (IGSO) / 111.75°E, 31° inclined orbit | Operational | |

| IRNSS-1E | I005 | I05 | 2016-003A | 41241 | 20 January 2016 | PSLV-XL-C31 | Geosynchronous (IGSO) / 111.75°E, 29° inclined orbit | Partial Failure | The satellite is being used for NavIC's short message broadcast service.[66][67] |

| IRNSS-1F | I006 | I06 | 2016-015A | 41384 | 10 March 2016 | PSLV-XL-C32 | Geostationary (GEO) / 32.5°E, 5° inclined orbit | Operational | |

| IRNSS-1G | I007 | I07 | 2016-027A | 41469 | 28 April 2016 | PSLV-XL-C33 | Geostationary (GEO) / 129.5°E, 5.1° inclined orbit | Partial Failure | The satellite is being used for NavIC's short message broadcast service.[49] |

| IRNSS-1H | 31 August 2017 | PSLV-XL-C39 | Launch Failed | The payload fairing failed to separate and satellite could not reach the desired orbit.[43][68] It was meant to replace defunct IRNSS-1A.[64][20] | |||||

| IRNSS-1I | I009 | I09 | 2018-035A | 43286 | 12 April 2018 | PSLV-XL-C41 | Geosynchronous (IGSO) / 55°E, 29° inclined orbit | Operational | [69] |

NVS series satellite

| Satellite | SVN | PRN | Int. Sat. ID | NORAD ID | Launch Date | Launch Vehicle | Orbit | Status | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVS-01 | I010 | I10 | 2023-076A | 56759 | 29 May 2023[70][71] | GSLV Mk II - F12[72] | Geostationary (GEO) / 129.5°E, 5.1° inclined orbit | Operational | Planned replacement of IRNSS-1G. Features extended lifespan, indigenous clock and new civilian band L1 for low power devices.[49][73][74] |

| NVS-02 | 2024-2025 | GSLV Mk II | Geosynchronous (IGSO), 32.5°E or 129.5°E, 29° inclined orbit | Planned | [49][75][76] | ||||

| NVS-03 | TBD | GSLV Mk II | Geosynchronous (IGSO), 32.5°E or 129.5°E, 29° inclined orbit | Planned | [49][75][76] | ||||

| NVS-04 | TBD | GSLV Mk II | Geosynchronous (IGSO), 32.5°E or 129.5°E, 29° inclined orbit | Planned | [49][75][76] | ||||

| NVS-05 | TBD | GSLV Mk II | Geosynchronous (IGSO), 32.5°E or 129.5°E, 29° inclined orbit | Planned | [49][75][76] |

Clock failure

In 2017, it was announced that all three SpectraTime supplied rubidium atomic clocks on board IRNSS-1A had failed, mirroring similar failures in the European Union's Galileo constellation.[77][78] The first failure occurred in July 2016, followed soon after by the two other clocks on IRNSS-1A. This rendered the satellite non-functional and required replacement.[79] ISRO reported it had replaced the atomic clocks in the two standby satellites, IRNSS-1H and IRNSS-1I in June 2017.[20] The subsequent launch of IRNSS-1H, as a replacement for IRNSS-1A, was unsuccessful when PSLV-C39 mission failed on 31 August 2017.[20][80] The second standby satellite, IRNSS-1I, was successfully placed into orbit on 12 April 2018.[69]

In July 2017, it was reported that two more clocks in the navigational system had also started showing signs of abnormality, thereby taking the total number of failed clocks to five,[20] in May 2018 a failure of a further 4 clocks was reported, taking the count to 9 of the 24 in orbit.[81]

As a precaution to extend the operational life of navigation satellite, ISRO is running only one rubidium atomic clock instead of two in the remaining satellites.[20]

As of May 2023 only four satellites are capable of providing navigation services[82] which is the minimum number required for service to remain operational.[83]

Indian Atomic clock

In order to reduce the dependency on imported frequency standards ISRO's Space Applications Centre (SAC), Ahmedabad had been working on domestically designed and developed Rubidium based atomic clocks.[3][84][85][86] To overcome the clock failures on first generation navigation satellites and its subsequent impact on NavIC's position, navigation, and timing services, these new clocks would supplement the imported atomic clocks in next generation of navigation satellites.[87][88][89][90]

On 5 July 2017, ISRO and Israel Space Agency (ISA) signed an Memorandum of Understanding to collaborate on space qualifying a Rubidium Standard based on AccuBeat model AR133A and to test it on an ISRO satellite.[5]

Future developments

India's Department of Space in their 12th Five Year Plan (FYP) (2012–17) stated increasing the number of satellites in the constellation from 7 to 11 to extend coverage.[86] These additional four satellites will be made during 12th FYP and will be launched in the beginning of 13th FYP in geosynchronous orbit of 42° inclination.[91][92] Also, the development of space-qualified Indian made atomic clocks was initiated,[85] along with a study and development initiative for an all optical atomic clock (ultra stable for IRNSS and deep space communication).[84][86]

ISRO will be launching five next generation satellite featuring new payloads and extended lifespan of 12 years. Five new satellites viz. NVS-01, NVS-02, NVS-03, NVS-04 and NVS-05 will supplement and augment the current constellation of satellites. The new satellites will feature the L5 and S band and introduces a new interoperable civil signal in the L1 band in the navigation payload and will use Indian Rubidium Atomic Frequency Standard (iRAFS.)[90][93][73][94] This introduction of the new L1 band will help facilitate NavIC proliferation in wearable smart and IoT devices featuring a low power navigation system. NVS-01 is a replacement for IRNSS-1G satellite and will launch on GSLV in 2023.[95][49]

Global Indian Navigation System

Study and analysis for the Global Indian Navigation System (GINS) was initiated as part of the technology and policy initiatives in the 12th FYP (2012–17).[84] The system is supposed to have a constellation of 24 satellites, positioned 24,000 km (14,913 mi) above Earth. As of 2013, the statutory filing for frequency spectrum of GINS satellite orbits in international space, has been completed.[96] As per new 2021 draft policy,[97] ISRO and Department of Space (DoS) is working on expanding the coverage of NavIC from regional to global that will be independent of other such system currently operational namely GPS, GLONASS, BeiDou and Galileo while remain interoperable and free for global public use.[98] ISRO has proposed to Government of India to expand the constellation for global coverage by initially placing twelve satellites in Medium Earth Orbit (MEO).[31]

See also

References

- 1 2 Datta, Anusuya (14 March 2018). "CAG pulls up ISRO on NavIC delays, cost overruns". Geospatial World.

- ↑ "IRNSS-1G exemplifies 'Make in India', says PM". The Statesman. 28 April 2016. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Satellites are in the sky, but long way to go before average Indians get Desi GPS | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. 8 June 2018.

- ↑ "IRNSS Programme - ISRO". isro.gov.in. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- 1 2 "NavIC: How is India's very own navigation service different from US-owned GPS?". Firstpost. 27 September 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ↑ "Orbit height and info". Archived from the original on 30 December 2015.

- ↑ "IRNSS details". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Isro to launch 5th navigation satellite on Jan 20, first in 2016". Hindustan Times. 18 January 2016.

- ↑ Rohit KVN (28 May 2017). "India's own GPS IRNSS NavIC made by ISRO to go live in early 2018". International Business Times.

- ↑ "Isro's PSLV-C32 places India's sixth navigation satellite IRNSS-1F in orbit". The Times of India.

- ↑ "ISRO puts seventh and final IRNSS navigation satellite into orbit". The Times of India.

- ↑ "IRNSS-1I up in space, completes first phase of Indian regional navigation constellation". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- 1 2 "Government of India, Ministry of Space, Lok Sabha - Unstarred Question number: 483 on Progress of IRNSS". 20 November 2019. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Government of India, Ministry of Space, Lok Sabha, Unstarred Question No: 675 on Indigenous GPS". 26 June 2019. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- 1 2 "After Isro-Qualcomm pact, NavIC-compatible mobiles, navigation devices to hit market next year". The Times of India. 16 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ↑ "NavIC: List of Supported Phones and Difference between NavIC and GPS". Get Droid Tips. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ↑ "Qualcomm Clears Confusion Over NavIC Support on Snapdragon Devices". NDTV Gadgets 360. 2 March 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ↑ "NavIC: Supported Phones & How is it Better than GPS?". DealNTech. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ↑ Sha, Arjun (4 March 2020). "List of Smartphones with NavIC Support (Regularly Updated)". Beebom. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Navigation satellite clocks ticking; system to be expanded: ISRO". The Economic Times. 10 June 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Srivastava, Ishan (5 April 2014). "How Kargil spurred India to design own GPS". The Times of India. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ↑ Raj, N. Gopal (26 June 2013). "India prepares to establish navigation satellite system". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

The project to establish the IRNSS at a cost of Rs. 1,420 crores was approved by the Union Government in June 2006.

- ↑ "ISRO opens navigation centre for satellite system". Zeenews.com. 28 May 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ "India Making Strides in Satellite Technology". Defence News. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ "India's first ever dedicated navigation satellite launched". DNA India. 2 July 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ "India's first dedicated navigation satellite placed in orbit". NDTV. 2 July 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ "IRNSS Signal in Space ICD Released". GPS World. 25 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ Sarkar, Debashis (21 January 2020). "Qualcomm launches three chipsets with Isro's Navic GPS for Android smartphones". The Times of India.

- ↑ "Launch of mobile chipset compatible to NavIC - ISRO". Department of Space, Indian Space Research Organisation. Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ "NavIC support in upcoming Mobile, Automotive and IoT Platforms is poised to deliver superior Location-Based services to India's Industries and Technology Ecosystem Through Qualcomm". Indian Space Research Organisation. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- 1 2 Koshy, Jacob (26 October 2022). "ISRO to boost NavIC, widen user base of location system". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ↑ Bordoloi, Pritam (3 October 2022). "India's Indigenous Navigation System Can Make Your Phones Expensive". Analytics India Magazine. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ↑ "US Congress consents to designate India's NavIC as allied system". The Economic Times. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ↑ S. Anandan (10 April 2010). "Launch of first satellite for Indian Regional Navigation Satellite system next year". The Hindu. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ↑ H. Pathak. "3 Satellites To Be Launched By ISRO". Archived from the original on 17 April 2011.

- ↑ "ISRO's Future programme". ISRO. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ↑ "Countdown begins for PSLV-C22 launch". Business Line. 29 June 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ↑ "Isro successfully launches navigation satellite IRNSS-1B". The Times of India. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ↑ "ISRO puts India's Navigation satellite IRNSS 1B into orbit". news.biharprabha.com. Indo-Asian News Service. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ↑ "India successfully launches IRNSS-1D, fourth of seven navigation satellites". The Times of India. 28 March 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ "India launches 5th navigation satellite IRNSS-1E powered by PSLV rocket". Hindustan Times. 20 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Narasimhan, T. E. (29 April 2016). "India gets its own GPS with successful launch of 7th navigation satellite". Business Standard. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- 1 2 "ISRO says launch of navigation satellite IRNSS-1H unsuccessful". The Economic Times. 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ↑ "IRNSS-1I". isro.gov.in. Indian Space Research Organisation. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ↑ "PSLV-C41/IRNSS-1I". isro.gov.in. Indian Space Research Organisation. 12 April 2018. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "IRNSS". isac.gov.in. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ↑ "First IRNSS satellite by December". Magazine article. Asian Surveying and Mapping. 5 May 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ↑ "How Kargil spurred India to design own GPS". The Times of India. 5 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "ANNUAL REPORT 2020-2021" (PDF). ISRO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ K. Radhakrishnan (29 December 2013). "Mars and more, final frontier". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Annual Report 2019-20". Department of Space. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ↑ "75 Major Activities of ISRO" (PDF). 3 February 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2022.

ISTRAC has established a network of stations to support IRNSS satellites consisting of four IRCDR stations (Hassan, Bhopal, Jodhpur and Shillong), 16 IRIMS stations (Bengaluru, Hassan, Bhopal, Jodhpur, Shillong, Dehradun, Port Blair, Mahendragiri, Lucknow, Kolkata, Udaipur, Shadnagar, Pune and Mauritius). ISTRAC has also established ISRO Navigation Centre-1, including an IRNWT facility at Bengaluru and ISRO Navigation Centre-2, including an IRNWT facility at Lucknow.

- ↑ Kunhikrishnan, P (20 June 2019). "Update on ISRO's International Cooperation" (PDF). p. 5.

Brunei, Indonesia, Australia, Russia, France, Japan (IRIMS)

- ↑ "Quad push: ISRO taking space ties with US, Japan and Australia to a higher orbit". The Economic Times. 16 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ↑ "India, France Working On 3rd Joint Space Mission, Says ISRO Chairman". NDTV. 20 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ↑ "Gaganyaan, India's human space mission, will use 'green propulsion': ISRO". Hindustan Times. 26 March 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ "Navigation Indian Constellation (NAVIC)". ESA. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ↑ "Indian 'GPS' for public use by year-end". The Times of India. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ↑ "Indian 'GPS' for public use by year-end". The Times of India. 5 March 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ↑ A. Bhaskaranarayana Director SCP/FMO & Scientific Secretary Indian Space Research Organisation – Indian IRNSS and GAGAN Archived 5 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "GPS.gov: GPS Accuracy". www.gps.gov. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ↑ "Get ready! India's own GPS set to hit the market early next year - Times of India". The Times of India. 28 May 2017.

- 1 2 "IGS MGEX NavIC". mgex.igs.org. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- 1 2 Mukunth, Vasudevan. "3 Atomic Clocks Fail Onboard India's 'Regional GPS' Constellation". thewire.in. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ↑ D.S., Madhumathi. "Atomic clocks on indigenous navigation satellite develop snag". The Hindu. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ↑ "NavIC and GAGAN System Updates" (PDF). Retrieved 1 June 2023.

NavIC is offering short messaging service for users in Indian region through IRNSS-1A and 1E satellites.

- ↑ "IRNSS-1H launch unsuccessful, says ISRO". The Indian Express. 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- 1 2 "India completes NavIC constellation with 7th satellite - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ↑ "Isro to launch navigation satellite NVS-01 on May 29". Hindustan Times. 14 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ↑ "Isro to launch new navigation satellite on May 29". The Times of India. 16 May 2023. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ↑ "Monthly Summary of Department of Space for February 2023" (PDF). 10 March 2023.

- 1 2 "Isro aims for 7 more launches from India in 2021". Times of India. 12 March 2021.

- ↑ "2nd-gen ISRO navigation satellite launches today". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "Overview of New NavIC L1 SPS Signal Structure & SBOC Modulation and Modified-CEMIC Multiplexing Scheme" (PDF). 29 September 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "NavIC and GAGAN System Update" (PDF). 28 September 2021.

- ↑ "SpectraTime to Supply Atomic Clocks to IRNSS | Inside GNSS". www.insidegnss.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ "Spectratime Awarded Contract To Supply Rubidium Space Clocks To IRNSS". spacedaily.com. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ D.S., Madhumathi. "Atomic clocks on indigenous navigation satellite develop snag". The Hindu. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ↑ Vasudevan Mukund (2 September 2017). "India's 'GPS' Remains Unfinished". The Wire. Wayback Machine. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ D.S., Madhumathi (5 May 2018). "ISRO's clock to prop up India's own GPS". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ↑ "New NavIC satellite launching today: why a regional navigation system matters to India". The Indian Express. 29 May 2023. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

Currently, only four IRNSS satellites are able to provide location services, according to ISRO officials. The other satellites can only be used for messaging services such as providing disaster warnings or potential fishing zone messages for fishermen.

- ↑ "FAQ Navigation". www.isro.gov.in. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

For determining position and time, a minimum of four satellites are required.

- 1 2 3 "Report of Working Group (WG-14)" (PDF). Department of Space, Government of India. October 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- 1 2 "ISRO to test space robustness of indigenous atomic clocks this December". The Indian Express. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Five Year Plan" (PDF). Department of Space. 12th FYP: 96. October 2011.

- ↑ Bandi, Thejesh N.; Kaintura, Jaydeep; Saiyed, Azhar R.; Ghosal, Bikash; Jain, Pratik; Sharma, Richa; Priya, Priyanka; Shukla, Keya; Mandal, Sarathi; Reddy, Niranjan; Soni, Ashish; Somani, Sandip; Patel, Arvind; Attri, Deepak; Mishra, Deepak (March 2019). "Indian Rubidium Atomic Frequency Standard (IRAFS) Development for Satellite Navigation". 2019 URSI Asia-Pacific Radio Science Conference (AP-RASC). p. 1. doi:10.23919/URSIAP-RASC.2019.8738208. ISBN 978-908-25987-5-9. S2CID 195225382.

- ↑ "India developing atomic clocks for use on satellites". The Hindu. 20 May 2015. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ↑ "A desi atomic clock". India Today. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- 1 2 "Five new advanced navigation satellites for strategic needs – The New Indian Express". www.newindianexpress.com. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ↑ "The Interoperable Global Navigation Satellite Systems Space Service Volume" (PDF). pp. 62, 95. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ↑ "12th Five Year Plan report, Department of Space, DST" (PDF). dst.gov.in. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ "Indigenous Atomic Clock and Monitoring Unit for NavIC" (PDF). 10 December 2019.

- ↑ Bandi, Thejesh N.; Kaintura, Jaydeep; Saiyed, Azhar R.; Ghosal, Bikash; Jain, Pratik; Sharma, Richa; Priya, Priyanka; Shukla, Keya; Mandal, Sarathi; Reddy, Niranjan; Soni, Ashish (2019). "Indian Rubidium Atomic Frequency Standard (IRAFS) Development for Satellite Navigation". 2019 URSI Asia-Pacific Radio Science Conference (AP-RASC). p. 1. doi:10.23919/URSIAP-RASC.2019.8738208. ISBN 978-908-25987-5-9. S2CID 195225382.

- ↑ "Annual Report of Department of Space 2018-19" (PDF). 28 May 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ↑ "Global Indian Navigation system on cards". Business Line. 14 May 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ↑ "Indian Satellite Navigation Policy-2021 (SATNAV Policy-2021)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ↑ Dutt, Anonna (3 August 2021). "ISRO to expand reach of navigation system globally: New draft policy". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

Footnotes

- ^ SATNAV Industry Meet 2006. ISRO Space India Newsletter. April – September 2006 Issue.

External links

- IRNNS programme Archived 2 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Official Website

- IRNSS Programme at ISRO