The Indian harmonium, hand harmonium, samvadini, peti ("box"), or vaja, often just called a harmonium, is a small and portable hand-pumped reed organ which is very popular in the Indian subcontinent.[1] The sound resembles an accordion or other bellows driven free-reed aerophones.[1]

Reed-organs arrived in India during the mid-19th century, possibly with missionaries or traders.[2] Over time they were modified by Indian craftsmen to be played on the floor (since most traditional Indian music is done in this fashion), and to be smaller and more portable.[1]

This smaller Indian harmonium quickly became very popular in the Indian music of the 19th and 20th century. It also became widely used for Indian devotional music played in temples and in public. The Indian harmonium is still widely used today by Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims and Buddhists for devotional genres like qawwali, ghazal, kirtan and bhajan. In South Asia, the harmonium is most widely used to accompany vocalists.[1]

The Indian harmonium has also recently become popular in the Western yoga subculture. It was popularized by American kirtan singers like Krishna Das and Jai Uttal.

A related instrument is the Shruti box, a keyless harmonium, used only to produce drones to support other soloists.

History

Development during the 19th century

The European harmonium developed in the 18th century, inspired by the Chinese Sheng, a gourd mouth organ.[3] Various types of European harmoniums and reed-organs arrived in India in the 19th century, some were brought by missionaries.[2][1]

The Indian harmonium is derived from reed organ (pump organ) designs developed in France. Originally, these were large instruments, designed to be played sitting on a chair, which allowed one to pump the instrument using foot pedals.[4] Over time, Europeans designed smaller harmoniums, like the Guide-chant, which included manually pumped bellows.[5]

Indian craftsmen soon created a much smaller instrument based on the European designs, which was made to rest on the floor with bellows that were pumped with the left hand. Other elements were added, like the addition of drone stops (the use of drones is important in Indian music). This instrument quickly became popular: it was lightweight and thus portable, reliable, easy to learn and produced a rich sound.[6] Dwarkanath Ghose of the Dwarkin company is often considered to be one of the first inventors of the Indian style harmonium.[4]

Dwijendranath Tagore is credited with having used the imported instrument in 1860 in his private theatre, but it was probably a pedal-pumped instrument that was cumbersome or possibly some variation of the reed organ. Initially, it aroused curiosity, but gradually people started playing it,[7] and Ghose took the initiative to modify it.[4] It was in response to Indian needs that the new harmonium was introduced. All Indian musical instruments are played with the musician sitting on the floor or a stage, behind the instrument or holding it in his hands. In that era, Indian homes did not use tables and chairs.[4]

Furthermore, in Western music, which is harmonically based, both a player's hands were needed to play the chords, thus assigning the bellows to the feet was the best solution; in Indian music, which is melodically based, only one hand was necessary to play the melody, and the other hand was free for the bellows.

Controversy in the 20th century

The harmonium was widely accepted throughout Indian music in the late 19th century. By the early 20th century, however, in the context of Indian nationalist movements that sought to depict India as separate from the West, the harmonium was portrayed as an unwanted foreign interloper.

From the point of view of Indian classical music, there were also technical concerns with the harmonium, including its inability to produce slurs, gamaka (playing semi-tone between notes) and meend (slides between notes) which can be done in instruments like Sitar and Sarod,[2] and the fact that, as a keyboard instrument, it is set to specific pitches.[2][6] Unlike a stringed instrument, its pitches cannot be adjusted in the course of performance.

The inability to slide between notes prevents it from articulating the subtle inflections (such as andolan, gentle oscillation) so crucial to many of the ragas of Indian classical music. The fact that the instrument is set to specific pitches also makes it less compatible to the classical Indian concept of svara, which doesn't focus on specific pitches, but a range of pitches.[2] The fixed pitches prevent it from articulating the subtle differences in intonational color between a given svara in two different ragas.[2] For these reasons, it was banned from All India Radio from 1940 to 1971.[2]

On the other hand, many of the harmonium's qualities suited it very well for the newly reformed classical music of the early 20th century: it is easy for amateurs to learn; it supports group singing and large voice classes; it provides a template for standardized raga grammar; it is loud enough to provide a drone in a concert hall. For these reasons, it has become the instrument of choice for accompanying most North Indian classical vocal genres, with top vocalists (e.g., Bhimsen Joshi) routinely using harmonium accompaniment in their concerts. Furthermore, some Indian musicians also made use of the harmonium as a solo instrument, including Pandit Bhishmadev Vedi, Pandit Muneshwar Dayal, Pandit Montu Banerjee, and Pamabhusan JnanPrakash Ghosh.[6]

The harmonium is still disliked by some connoisseurs of Indian music, who prefer the sarangi as an accompanying instrument for khyal singing.[6]

The musical concerns regarding the limitations of the harmonium also led to new technical innovations which attempted to craft a harmonium that was more suited to classical Indian music. One of these attempts is the work of Bhishmadev Vedi who is said to have been the first to contemplate improving the harmonium by augmenting it with a swarmandal (harp-like string box) attached to the top of the instrument. His disciple, Manohar Chimote, later implemented this concept, also making the instrument more responsive to key pressure, and called the instrument a samvadini—a name now widely accepted.[8][6] Bhishmadev Vedi is also said to have been among the first to contemplate and design compositions specifically for the harmonium, styled along the lines of "tantakari"—performance of music on stringed instruments. These compositions tend to have a lot of cut notes and high-speed passages, creating an effect similar to that of a string being plucked.

In 1954, Late Jogesh Chandra Biswas first modified the then-existing harmoniums, so it folds down into a much thinner space for easier maneuverability. Before that, if the instrument was boxed, it used to need two people to carry it, holding it from either side. This improvisation became a generic design in most harmoniums since then and was coined with the term "Folding Harmoniums".

Another modification of the instrument is that by musicologist Vidyadhar Oke, who developed a 22-microtone harmonium, which can play 22 microtones as required in Indian classical music. The fundamental tone (Shadja) and the fifth (Pancham) are fixed, but the other ten notes have two microtones each, one higher and one lower. The higher microtone is selected by pulling out a knob below the key. In this way, the 22-shruti harmonium can be tuned for any particular raga by simply pulling out knobs wherever a higher shruti is required.

Construction and components

The basic components of an Indian harmonium include: a wooden body with two metal handles for carrying, banks of brass reeds (often 1, 2, or 3) set on a wooden reed board, a pumping apparatus (bellows), air stops (including stops for drones), and a keyboard (which is similar to a piano keyboard but with a smaller number of keys).[9] Some models include an octave coupler, a mechanism which links one reed valve with another note (usually the same note an octave above or below).[9]

The sound is produced by the air, which is pumped by the bellows into an internal reservoir bellows inside the harmonium. Air from this inner reservoir escapes to vibrate the reeds. This allows for a continuously sustained sound.[9]

Types

There are two main styles of standard Indian Harmoniums (i.e. equi-tempered harmoniums) built in India: Delhi style and Kolkata style. Each style traditionally uses different types of wood, construction methods and designs, resulting in a different sound and feel.

Delhi style harmoniums are typically less expensive than Kolkata style harmoniums, which tend to be more high end. Kolkata style harmoniums often have three or four banks of reeds (while Delhi style usually comes with just two banks). They also are commonly made of hardwood, like teak (Delhi style is more often made of softwoods). These differences makes Kolkata style harmoniums more expensive, but their sound is significantly fuller and their range is larger. Kolkata style harmoniums are also commonly designed with scale changers which allows one to slide the keyboard to change scale without changing chord positions. This further adds to the cost.

Regarding Harmoniums made in Pakistan, Lahore style (sometimes called Qawwali style or Pakistani) harmoniums are also unique in their construction. Lahore style harmoniums typically lack the numerous stop and drone knobs found in harmoniums built in India. Higher end models also commonly feature the rare German Jubilate Harmonium reeds. They may also come with a right upper action octave coupler that is permanently engaged.

Some harmoniums (sometimes named "portable" or "travel" models) also come with a built in wooden suitcase. The top of the suitcase is detachable, and the keyboard is then raised for playing.[10]

Aside from the main construction styles, harmoniums also come in several different sizes, and as such, their sound varies depending on its construction. Smaller builds may also have a smaller number of keys. The standard number is a 42 key keyboard, but smaller versions may have 39 or 32 keys. Smaller models may be built in slightly different designs as well, or they may be simple smaller versions of the classic design. Small models generally have less sustain and a sound which is less full, since the sound box is significantly smaller.

Another rarer and more expensive type of harmonium is the 22 shruti (22 microtone) harmonium. These are used specifically for Indian classical music since they can replicate the 22 microtones used in Indian classical music, a feat that other models cannot accomplish.

Usage

.jpg.webp)

The harmonium is an important instrument in many genres of Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi music. It is used in many South Asian musical genres including North Indian classical music forms like Dhrupad and Kheyal, Sufi Muslim Qawwali music, Hindu and Sikh devotional (bhakti) music (Bhajan and Kirtan), as well as Folk music, Filmi Sangeet (Indian Film Music), Ghazal, Geet, Dhamar, Thumri, and Shabad.[11][12]

In most genres, the Indian harmonium is commonly accompanied by some percussion instrument which provides the tala to the music, such as the tabla, dholak, taal, or mridangam.

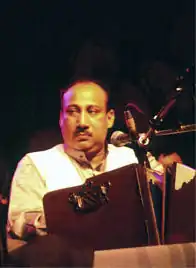

Almost all Qawwals use the harmonium as musical accompaniment.[13] It has received international exposure as the genre of Qawwali music has been popularized by renowned Pakistani musicians, including Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (1948–1997) and Aziz Mian (1942–2000).[13]

Harmoniums are commonly found in gurdwaras (Sikh temples) around the world, where is it commonly used for Shabad kirtan devotional chanting. To Sikhs, the harmonium is known as the vaja or baja (ਵਾਜਾ; Vājā). It was widely adopted by Sikhs during the 19th and 20th century, often replacing native instruments.[14] It is also referred to as a peti (literally, box) in some parts of North India and Maharashtra (where it is widely used in Marathi kirtan).

The Indian harmonium came to the western world during the spread of Indian religions to the west in the 20th century. Indian religious movements like the International Society for Krishna Consciousness's (ISKCON) and Yogi Bhajan's 3HO brought Indian devotional kirtan to the West, which included the use of the harmonium.[15] Western kirtan singers like Krishna Das, Jai Uttal, and Snatam Kaur have become well known harmonium players, especially in the new age and yoga subcultures.[16][17]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brahaspati, S.V. (2023). How to Play Harmonium, p. 3. Abhishek Publications.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Small encyclopedia with Indian instruments". india-instruments.com.

excerpt of Suneera Kasliwal, Classical Musical Instruments, Delhi 2001

- ↑ Brahaspati, S.V. (2023). How to Play Harmonium, p. 5. Abhishek Publications.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Invention of Hand Harmonium". Dwarkin & Sons (P) Ltd. Archived from the original on 2007-04-09. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ "guide-chant". Dictionnaires et Encyclopédies sur 'Academic' (in French). Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brahaspati, S.V. (2023). How to Play Harmonium, p. 7. Abhishek Publications.

- ↑ Khan, Mobarak Hossain (2012). "Harmonium". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ "About Samvadini". Sydney: Samvad (music centre). Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Brahaspati, S.V. (2023). How to Play Harmonium, p. 6. Abhishek Publications.

- ↑ Brahaspati, S.V. (2023). How to Play Harmonium, p. 9. Abhishek Publications.

- ↑ Jones, L. JaFran (1990). "Review of Sufi Music of India and Pakistan.: Sound, Context and Meaning in Qawwali". Asian Music. 21 (2): 151–155. doi:10.2307/834116. ISSN 0044-9202. JSTOR 834116.

- ↑ Brahaspati, S.V. (2023). How to Play Harmonium, p. 7-26. Abhishek Publications.

- 1 2 Brahaspati, S.V. (2023). How to Play Harmonium, p. 8. Abhishek Publications.

- ↑ "Sikh Saaj | Other | Tabla – Discover Sikhism". www.discoversikhism.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ↑ Jackson, Carl T. (1994). Vedanta for the West. Indiana University Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-253-33098-X.

- ↑ Goodman, Frank (January 2006). "Interview with Krishna Das" (PDF). Puremusic (61). Retrieved 2014-01-15.

- ↑ Eckel, Sara (2009-03-05). "Chanting Is an Exercise in Body and Spirit". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

.jpg.webp)