| Indo-Pakistani Naval War of 1971 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bangladesh Liberation War and Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Supported by: | Supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

1 light cruiser 5 destroyers 2 frigates 4 submarines (3 Daphné class and 1 Tench class) 6 midget submarines 8 minesweeper 1 tanker Two ex Royal Saudi Navy fast Jaguar class patrol craft[20] At least 1 Indonesian naval vessel[21] US 7th Fleet |

1 aircraft carrier 2 light cruisers 3 destroyers 14 frigates 5 ASW frigates 6 missile ships 2 tankers 1 repair ship 2 landing ships (Polnocny class) 2 groups of Soviet cruisers and destroyers 1 Soviet submarine[2] 1 Soviet nuclear submarine[22][23] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

1,900 killed in action †

18 cargo, supply and communication ships

|

194 killed in action † | ||||||||

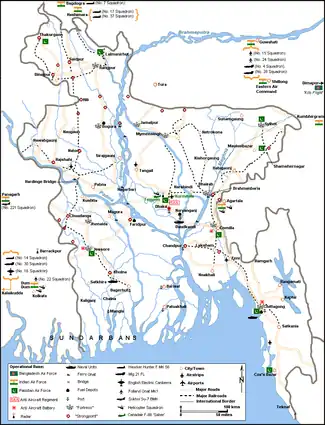

The Indo-Pakistani Naval War of 1971 refers to the maritime military engagements between the Indian Navy and the Pakistan Navy during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. The series of naval operations began with the Indian Navy's exertion of pressure on Pakistan from the Indian Ocean, while the Indian Army and Indian Air Force moved in to choke Pakistani forces operating in East Pakistan on land. Indian naval operations comprised naval interdiction, air defence, ground support, and logistics missions.

With the success of Indian naval operations in East Pakistan, the Indian Navy subsequently commenced two large-scale operations: Operation Trident and Operation Python. These operations were focused on West Pakistan, and preceded the start of formal hostilities between India and Pakistan.

Background

The Indian Navy did not play a major role during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 as the war focused on land-based conflict. On 7 September, a flotilla of the Pakistan Navy under the command of Commodore S.M. Anwar carried out a bombardment, Operation Dwarka, of the Indian Navy's radar station of Dwarka, 200 miles (320 km) south of the Pakistani port of Karachi. While there was no damage to the radar station,[1] this operation caused the Indian Navy to undergo a rapid modernization and expansion. Consequently, the Indian Navy budget grew from ₹ 350 million to ₹ 1.15 billion. The Indian Navy added a squadron to its combatant fleet by acquiring six Osa-class missile boats from the Soviet Union. The Indian Naval Air Arm was also strengthened.

Pakistani Navy in East Pakistan

The Eastern Command was established in 1969 and Rear-Admiral Mohammad Shariff (later four-star Admiral) was made naval commander in that region. Admiral Shariff administratively ran the Navy, and was credited for leading the administrative operations. Under his command, SSG(N), Pakistan Marines and SEAL teams were established, running both covert and overt operations in the Eastern Command.

The Pakistan Naval Forces had inadequate ships to challenge the Indian Navy on both fronts, and the PAF was unable to protect these ships from the Indian Air Force and Indian Naval Air Arm. Furthermore, Chief of Naval Staff of Pakistan Navy, Vice-Admiral Muzaffar Hassan, had ordered the navy to deploy all naval power on the Western Front. Most of the Pakistan Navy's combatant vessels were deployed in West Pakistan and only one destroyer, PNS Sylhet, was assigned in East Pakistan, on the personal request of Admiral Shariff.

During the conflict, East Pakistan's naval ports were left defenceless as the Eastern Command of Pakistan had decided to fight the war without the navy. Faced with overwhelming opposition, the navy planned to remain in the ports when war broke out.[34]

In the eastern wing, the Pakistan Navy heavily depended on her gun boat squadron.[35] The Pakistan's Eastern Naval Command was in direct command of Flag Officer Commanding (FOC) Rear-Admiral Mohammad Shariff who also served as the right-hand of Lieutenant-General Niazi. The Pakistan Navy had 4 gun boats (PNS Jessore, Rajshahi, Comilla, and Sylhet). The boats were capable of attaining maximum speed of 20 knots (37 km/h), were crewed by 29 sailors. Known as Pakistan Navy's brown water navy, the gun boats were equipped with various weapons, including heavy machine guns. The boats were adequate for patrolling and anti-insurgency operations but they were hopelessly out of place in conventional warfare.[36]

In the early part of April, the Pakistan Navy began naval operations around East Pakistan to support the Army's execution of Operation Searchlight. Rear-Admiral Mohammad Shariff had coordinated all of these missions. On 26 April, the Pakistan Navy successfully completed Operation Barisal, but it resulted in the temporary occupation of city of Barisal.

Bloody urban guerrilla warfare ensued and Operation Jackpot severely damaged the operational capability of Pakistan Navy. Before the start of the hostilities, all naval gun boats were stationed at the Chittagong.[37] As the air operations began, the IAF aircraft damaged the Rajshahi, while the Comilla was sunk on 4 December. On 5 December, the IAF sank two patrol boats in Khulna. The PNS Sylhet was destroyed on 6 December and the Balaghat on 9 December by Indian aircraft. On 11 December, the PNS Jessore was destroyed, while Rajshahi was repaired. The Rajashahi under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Sikandar Hayat managed to evade the Indian blockade and reach Malaysia before the surrender on 16 December.

Naval operations in the Eastern theatre

_with_a_Sea_King_helicopter_during_Indo-Pakistani_war_of_1971.jpg.webp)

The Indian Navy started covert naval operations, which were part of a larger operation named Operation Sea Sight which were executed successfully. In the end months of 1971, the Indian Navy's Eastern Naval Command had effectively applied a naval blockade that completely isolated East Pakistan's Bay of Bengal, trapping the Eastern Pakistan Navy and eight foreign merchant ships in their ports. The Pakistan Army's Combatant High Command, The GHQ, insisted and pressured the Pakistan Navy to deploy PNS Ghazi and to extend its sphere of naval operations into East Pakistan shores. The Officer in Command of Submarine Service Branch of Pakistan Navy opposed the idea of deploying an aging submarine, PNS Ghazi, in the Bay of Bengal. It was difficult to sustain prolonged operations in a distant area in the total absence of repair, logistics, and recreational facilities in the vicinity. At this time, submarine repair facilities were absent at Chittagong, the only sea port in the east during this period. Her commander and other officers objected the plan as when it was proposed by the senior Army and Naval officers.

In the Eastern wing of Pakistan, the Pakistan Navy had never maintained a squadron of warships, despite the calls made by Rear-Admiral Mohammad Shariff. Instead, a brown water navy was formed consisting a gun boats riverine craft on a permanent basis. Consequently, in eastern wing, repair and logistic facilities were not developed at Chittagong. The Indian Navy's Eastern Naval Command virtually faced no opposition from Eastern theatre. The aircraft carrier INS Vikrant, along with her escort LST ships INS Guldar, INS Gharial, INS Magar, and the submarine INS Khanderi, executed their operations independently.

On 4 December 1971, the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant was also deployed and its Hawker Sea Hawk attack aircraft contributed to Air Operations in East Pakistan. The aircraft successfully attacked many coastal towns in East Pakistan including Chittagong and Cox's Bazar. The continuous attacks later destroyed the PAF's capability to retaliate.[38]

The Pakistan Navy responded by deploying her ageing long-range submarine, PNS Ghazi, to counter the threat as the Naval Command had overruled the objections by her officers. The PNS Ghazi, under the command of Commander Zafar Muhammad Khan, was assigned to locate the INS Vikrant, but when it was not able to locate, decided to mine the port of Visakhapatnam – the headquarters of Eastern Naval Command.[39] The Indian Navy's Naval Intelligence laid a trap to sink the submarine by giving fake reports about the aircraft carrier. At around midnight of 3–4 December, the PNS Ghazi began its operation of laying mines. The Indian Navy dispatched INS Rajput to counter the threat.

The INS Rajput's sonar radar reported the disturbance underwater and two depth charges were released.[40] The deadly game ended when the submarine sank mysteriously while laying a mine with all 92 hands on board around midnight on 3 December 1971 off the Visakhapatnam coast.[41][42]

The sinking of Ghazi turned out to be a major blow and setback for Pakistani naval operations in East Pakistan.[43] It diminished the possibility of Pakistan carrying out large scale of naval operations in the Bay of Bengal. It also eliminated the threat posed by the Pakistan Navy to Indian Eastern Naval Command. On reconnaissance mission, the Ghazi was ordered to report back to her garrison on 26 November, and admitted a report Naval Combatant Headquarter, NHQ. However, it was failed to return to her garrison. Anxiety grew day by day at the NHQ and NHQ had pressed frantic efforts to establish communications with the submarine failed to produce results. By 3 December prior to starting of the war, the doubts about the fate of submarine had already begun to agitate the commanders at the Naval Headquarter (NHQ).

On 5/6 December 1971, naval air operations were carried out Chittagong, Khulna, and Mangla harbours, and at ships in the Pussur river. The oil installations were destroyed at Chittagong, and the Greek merchant ship Thetic Charlie was sunk at the outer anchorage. On 7/8 December, the airfields of PAF were destroyed, and the campaign continued until 9 December. On 12 December, Pakistan Navy laid mines on amphibious landing approaches to Chittagong. This proved a useful trap for some time, and it had denied any direct access to Chittagong port for a long time, even after the instrument of surrender had been signed. The Indian Navy therefore decided to carry out an amphibious landing at Cox's Bazar with the aim cutting off the line of retreat for Pakistan Army troops. On 12 December, additional amphibious battalion was aboard on INS Vishwa Vijaya was sailed from Calcutta port. On the night of 15/16 December, the amphibious landing was carried out, immediately after IAF bombardment of the beach a day earlier. After fighting for days, the human cost was very high for Pakistani forces, and no opposition or resistance was offered by Pakistani forces to Indian forces. During this episode Eastern theatre Indian forces suffered only 2 deaths in the operation. Meanwhile, Pakistani forces were reported to have suffered hundreds of deaths. By the dawn of 17 December, the Indian Navy was free to operate at will in the Bay of Bengal.

Furthermore, the successful Indian Air Operations and Operation Jackpot, led by the Bengali units with the support of Indian Army, undermined the operational capability of Pakistan Navy. Many naval officers (mostly Bengalis) had defected from the Navy and fought against the Pakistan Navy.[44] By the time Pakistan Defence Forces surrendered, the Navy had suffered heavy damage as almost all of the gun boats, destroyer (PNS Sylhet), and the long-range submarine, PNS Ghazi, were lost in the conflict, including their officers.

On 16 December, at 16:13hrs, Rear-Admiral Mohammad Shariff surrendered his Naval Command to Vice-Admiral Nilakanta Krishnan Commander-in-Chief of the Eastern Naval Command.[45] His TT Pistol is still placed in "cover glass" where his name is printed in big golden letters at the Indian Military Academy's Museum.[45] In 1972, U.S. Navy's Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and Indian Navy's Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Sardarilal Mathradas Nanda also paid him a visit with basket of fruits and cakes which initially surprised him, and was concern of his health.[45] While meeting with them, Admiral Shariff summed up that:

At the end of conflict.... We [Navy] had no intelligence and hence, were both deaf and blind with the Indian Navy and Indian Air Force pounding us day and night....

Sinking of INS Khukri

.jpg.webp)

As the Indian military offensive in East Pakistan increased, the Pakistan Navy had dispatched her entire submarine squadron on both fronts. Codename Operation Falcon, the Pakistan Navy began their reconnaissance submarine operations by deploying PNS Hangor, a Daphné class submarine, near the coastal water of West-Pakistan, and PNS Ghazi, Tench class long range submarine, near the coastal areas of East-Pakistan.

According to the Lieutenant R. Qadri, an electrical engineer officer at Hangor during the time, the assigned mission was considered quite difficult and highly dangerous, with the submarine squadron sailing under the assumption that the dangerous nature of this mission meant a great mortal risk to the submarine and her crew.

On the midnight of 21 November 1971, PNS Hangor, under the command of Commander Ahmed Tasnim, began her reconnaissance operations. Both PNS Ghazi and PNS Hangor maintained coordination and communication throughout patrol operations.

On 2 and 3 December, Hangor had detected a large formation of ships from Indian Navy's Western fleet which included cruiser INS Mysore. Hangor had passed an intelligence to Pakistan naval forces of a possible attack by the observed Indian Armada near Karachi. The Indian Naval Intelligence intercepted these transmissions, and dispatched two anti-submarine warfare frigates, INS Khukri and the INS Kirpan of 14th Squadron – Western Naval Command.

On 9 December 1971, at 1957 hours, Hangor sunk Khukri with two homing torpedoes. According to her commander, the frigate sank within the matter of two minutes.[47] The frigate sank with 192 hands on board. Hangor also attacked the INS Kirpan on two separate occasions, but the torpedoes had missed their target. Kirpan quickly disengaged and successfully evaded the fired torpedoes.

Attack on Karachi

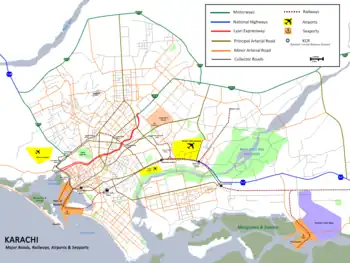

On 4 December, the Indian Navy, equipped with P-15 Termit anti-ship missiles, launched Operation Trident against the port of Karachi. In 1971, Karachi not only housed the headquarters of the Pakistan Navy[48] but was also the backbone of Pakistan's economy, as it served as the hub of Pakistan's maritime trade, meaning that any potential blockade of Karachi would be disastrous for Pakistan's economy. The defence of Karachi harbour was therefore paramount to the Pakistani High Command and it was heavily defended against any airstrikes or naval strikes. Karachi received some of the best defences Pakistan had to offer as well as cover from strike aircraft based at two airfields in the area.[49] The Indian fleet lay 250 miles from Karachi during the day, outside the range of Pakistani aircraft, and most of these aircraft did not possess night-bombing capability.[50] The Pakistani Navy had launched submarine operations to gather intelligence on Indian naval efforts. Even so, with multiple intelligence reports by the submarines, the Navy had failed to divert the naval attacks, due to misleading intelligence and communications.

The Indian Navy's preemptive strike resulted in an ultimate success. The Indian missile vessels, of the 25th missile boat squadron, successfully sunk the minesweeper PNS Muhafiz,[24][27][51][52] the destroyer PNS Khaibar[24][27][51][52][53] and the MV Venus Challenger[51][54][55] which, according to Indian sources, was carrying ammunition for Pakistan from the United States forces in Saigon.[52][55][56] The destroyer PNS Shah Jahan was damaged beyond repair.[24][51][52][53][54] The missile ships also bombed the Kemari oil storage tanks of the port which were burnt and destroyed causing massive loss to the Karachi Harbour.[24] Operation Trident was an enormous success with no physical damage to any of the ships in the Indian task group, which returned safely to their garrison.[24]

Pakistan's Airforce retaliated by bombing Okha harbour, scoring direct hits on fuelling facilities for missile boats, ammunition dump and the missile boats jetty.[57][58] Though India had anticipated this assault and moved their missile boats to other locations prior thus preventing any losses,[55] the destruction of the special fuel tank prevented any further incursions until Operation Python.[55] On the way back from the bombing the PAF aircraft encountered an Alizé 203 Indian aircraft and shot it down.[29][30]

_launches_an_Alize_aircraft_during_Indo-Pakistani_War_of_1971.jpg.webp)

On 6 December, a false alarm by a Pakistani Fokker aircraft carrying naval observers caused a friendly fire confrontation between Pakistan's Navy and Air Force. A PAF jet mistakenly strafed the frigate PNS Zulfikar, breaking off shortly after the ship got itself recognised by frantic efforts. The crew suffered some casualties besides the damage to ship. The ship was taken back to port for repair.[59]

The Indian Navy launched a second large-scale operation on the midnight of 8 and 9 December 1971. The operation, codenamed Operation Python, was commenced under the command of Chief of Naval Staff of the Indian Navy Admiral S.M. Nanda.[60] The INS Vinash, a missile boat, and two multipurpose frigates, INS Talwar and INS Trishul participated in the operation. The attack squadron approached Karachi and fired four missiles. During the raid, the Panamanian vessel Gulf Star and the British ship SS Harmattan were sunk and Pakistan Navy's Fleet Tanker PNS Dacca received heavy damage.[24][27][52][61] More than 50% of Karachi's total fuel reserves were destroyed in the attack.[24][59] More than $3 billion[59] worth of economic and social sector damage was inflicted by the Indian Navy. Most of Karachi's oil reserves were lost and warehouses and naval workshops destroyed.[59] The operation damaged the Pakistani economy and hindered the Pakistan Navy's operations along the western coast.[62][63]

Ending

After the successful operations by Indian Navy, India controlled the Persian Gulf and Pakistani oil route.[64] The Pakistani Navy's main ships were either destroyed or forced to remain in port. A partial naval blockade was imposed by the Indian Navy on the port of Karachi and no merchant ship could approach Karachi.[62][65][66] Shipping traffic to and from Karachi, Pakistan's only major port at that time, ceased. Within a few days after the attacks on Karachi, the Eastern fleet of Indian Navy had success over the Pakistani forces in East Pakistan. By the end of the war, the Indian Navy controlled the seas around both the wings of Pakistan.[63]

The War ended for both the fronts after the Instrument of Surrender of Pakistani forces stationed in East Pakistan was signed at Ramna Race Course in Dhaka at 16.31 IST on 16 December 1971, by Lieutenant General A. A. K. Niazi, Commander of Pakistani forces in East Pakistan and accepted by Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, General Officer Commanding-in-chief of Eastern Command of the Indian Army.

The Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Navy's Eastern Naval Command Vice Admiral Nilakanta Krishnan also received the Naval surrender from the Flag Officer East Pakistan Navy, Rear Admiral Mohammad Shariff.[67] Sharif surrendered his TT pistol to Krishnan at 1631 hrs saying "Admiral Krishnan, Sir, soon I will be disarmed. Your Navy fought magnificently and had us cornered everywhere. There is no one I would like to surrender my arms to other than the Commander-in-Chief of the Eastern Fleet."[68] The TT Pistol is still placed in a covered glass display at the Indian Military Academy's Museum.[67]

The damage inflicted on the Pakistani Navy stood at 7 gunboats, 1 minesweeper, 1 submarine, 2 destroyers, 3 patrol craft belonging to the coast guard, 18 cargo, supply and communication vessels, and large scale damage inflicted on the naval base and docks in the coastal town of Karachi. Three merchant navy ships – Anwar Baksh, Pasni and Madhumathi –[26] and ten smaller vessels were captured.[27] Around 1900 personnel were lost, while 1413 servicemen were captured by Indian forces in Dhaka.[69] According to one Pakistan scholar, Tariq Ali, the Pakistan Navy lost a third of its force in the war.[70]

Admiral Shariff wrote in a 2010 thesis that "the generals in Air Force and Army, were blaming each other for their failure whilst each of them projected them as hero of the war who fought well and inflicted heavy casualties on the advancing Indians".[71] At the end, each general officers in the Air Force and Army placed General Niazi's incompetency and failure as responsible for causing the war, Sharif concluded.[71] Sharif also noted that:

The initial military success (Searchlight and Barisal) in regaining the law and order situation in East-Pakistan in March of 1971 was misunderstood as a complete success.... In actuality, the law and order situation deteriorated with time, particularly after September of the same year when the population turned increasingly against the [Pakistan] Armed Forces as well as the [Yahya's military] government. The rapid increase in the number of troops though bloated the overall strength, however, [it] did not add to our fighting strength to the extent that was required. A sizeable proportion of the new additions were too old, inexperienced or unwilling....

— Rear Admiral Mohammad Sharif, Flag Officer Commanding, Eastern Naval Command (Pakistan), [71]

See also

- PNS Muhafiz

- INS Khukri

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

- Timeline of the Bangladesh Liberation War

- Military plans of the Bangladesh Liberation War

- Mitro Bahini order of battle

- Pakistan Army order of battle, December 1971

- Evolution of Pakistan Eastern Command plan

- 1971 Bangladesh genocide

- Operation Searchlight

- Indo-Pakistani wars and conflicts

- Military history of India

- List of military disasters

- List of wars involving India

References

- 1 2 "The Shelling of Dwarka". bharat-rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- 1 2 "1971 India Pakistan War: Role of Russia, China, America and Britain". The World Reporter. 30 October 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ↑ "British aircraft carrier 'HMS Eagle' tried to intervene in 1971 India – Pakistan war – Frontier India – News, Analysis, Opinion – Frontier India – News, Analysis, Opinion". Frontier India. 18 December 2010. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ Patranobis, Sutirtho (10 June 2011). "Pak thanks Lanka for help in 1971 war". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Hariharan, R. (28 July 2012). "A tale of two interventions". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Maclaren, James (19 December 2018). "Last secret of the 1971 India-Pakistan War". Daily News. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Qureshi, Ammar Ali (2 December 2016). "Neighbours of many surprises". The Friday Times. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Hoodbhoy, Pervez (22 January 2012). "The Bomb: Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Vatanka, Alex (29 January 2016). "Why Pakistan Is the Biggest Winner in the Iranian-Saudi Dispute". Middle East Institute. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Rakesh Krishnan Simha (20 December 2011). "1971 War: How Russia sank Nixon's gunboat diplomacy". In.rbth.com. Russia & India Report. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ Archived 11 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "India – Pakistan War, 1971; Introduction". Acig.org. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ India's Foreign Policy. Pearson Education India. 2009. pp. 317–. ISBN 978-81-317-1025-8. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ Richard Edmund Ward (1 January 1992). India's Pro-Arab Policy: A Study in Continuity. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-0-275-94086-7. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ "Document 172". 2001-2009.state.gov. 10 December 1971. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Singh, Bhopinder (28 February 2020). "Turkey & Subcontinent". The Statesman. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Ramani, Samuel (4 July 2016). "Can Bangladesh and Turkey Mend Frayed Ties?". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Gandhi, Sajit (16 December 2002). "The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971". National Security Archive. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Ahmed, Zahid Shahab; Bhatnagar, Stuti. "Gulf States and the Conflict between India and Pakistan" (PDF). Journal of Asia Pacific Studies (2010). 1 (2): 259–291 – via dev.humanitarianlibrary.org.

- ↑ GM Hiranandani (2000). Transition to Triumph: History of the Indian Navy, 1965–1975. Lancer Publishers. p. 130. ISBN 9781897829721.

- ↑ Rakesh Krishnan Simha (20 December 2011). "1971 War: How Russia sank Nixon's gunboat diplomacy | Russia & India Report". In.rbth.com. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Cold war games". Bharat Rakshak. Archived from the original on 15 September 2006. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- ↑ Birth of a nation. Indianexpress.com (11 December 2009). Retrieved on 14 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Bangladeshi War of Independence and Indo-Pakistani War of 1971". GlobalSecurity.org. 2000. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "The Sinking of the Ghazi". Bharat Rakshak Monitor, 4(2). Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- 1 2 "Utilisation of Pakistan merchant ships seized during the 1971 war". Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Damage Assesment [sic] – 1971 Indo-Pak Naval War" (PDF). B. Harry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2005. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ "How west was won...on the waterfront". Tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- 1 2 "Damage Assessment – 1971 Indo-Pak Naval War". Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ↑ "Pakistan Air Force Combat Expirence". GlobalSecurity.org. 9 July 2011.

Pakistan retaliated by causing extensive damage through a single B-57 attack on Indian naval base Okha. The bombs scored direct hits on fuel dumps, ammunition dump and the missile boats jetty.

- ↑ Dr. He Hemant Kumar Pandey & Manish Raj Singh (1 August 2017). INDIA'S MAJOR MILITARY & RESCUE OPERATIONS. Horizon Books ( A Division of Ignited Minds Edutech P Ltd), 2017. p. 117.

- ↑ Col Y Udaya Chandar (Retd) (2 January 2018). Independent India's All the Seven Wars. Notion Press, 2018.

- ↑ Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, p 135

- ↑ Salik, Siddiq, Witness To Surrender, p134

- ↑ Salik, Siddiq, Witness To Surrender, p135

- ↑ Bangladesh at War, Shafiullah, Maj. Gen. K.M. Bir Uttam, p 211

- ↑ IAF claim of PAF Losses

- ↑ Mihir K. Roy (1995) War in the Indian Ocean, Spantech & Lancer. ISBN 978-1-897829-11-0

- ↑ "End of an era: INS Vikrant's final farewell". 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Till, Geoffrey (2004). Seapower: a guide for the twenty-first century. Great Britain: Frank Cass Publishers. p. 179. ISBN 0-7146-8436-8. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ↑ Harry, B. (2001). "The Sinking of PNS Ghazi: The bait is taken". Bharat Rakhsak. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Shariff, Admiral (retired) Mohammad, Admiral's Diary, pp140

- ↑ Operation Jackpot, Mahmud, Sezan, p 14

- 1 2 3 4 Roy, Admiral Mihir K. (1995). War in the Indian Ocean. United States: Lancer's Publishers and Distributions. pp. 218–230. ISBN 1-897829-11-6.

- ↑ Geoffrey Till (21 February 2013). Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-136-25555-7.

- ↑ Till, Geoffry (2004). Sea Power: The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. Frank Class Publishers. p. 179. ISBN 0-7146-5542-2.

- ↑ Karim, Afsir (1996). Indo-Pak Relations: Viewpoints, 1989–1996. New Delhi: Lancer Publishers. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-897829-23-3.

- ↑ "How west was won…on the waterfront". Tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "The Sunday Tribune – Books". www.tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Hiranandani, G. M. (1965–1975). Transition to triumph: history of the Indian Navy. Barnes&Noble. ISBN 9781897829721.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harry, B. "Trident, Grandslam and Python: Attacks on Karachi". Pages from History. Bharat Rakshak. Archived from the original on 7 December 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- 1 2 Petrie, John N. (December 1996). American Neutrality in the 20th Century: The Impossible Dream. DIANE Publishing. p. 110. ISBN 9780788136825.

- 1 2 Kopp, Carlo (5 July 2005). "Anti-Shipping Strike Combat Losses – Post 1966". Warship Vulnerability: 1. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ "1971 War: The First Missile Attack on Karachi". Indian Defence Review. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ "PAF Falcons – Picture Gallery – Aviation Art by Group Captain Syed Masood Akhtar Hussaini". Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ↑ John Pike. "Pakistan Air Force Combat Experience". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Harry, B. (7 July 2004). "Operation Trident, Grandslam and Python: Attacks on Karachi". History 1971 India-Pakistan War. Bharat Rakhsak. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009.

- ↑ Nadkarni, Admiral (retd) J. G. "Our superiority will prevail". In.rediff.com. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Trident, Grandslam and Python: Attacks on Karachi". History 1971 India-Pakistan War. Bharat-Rakshak. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- 1 2 "China's pearl in Pakistan's waters". Asia Times. 4 March 2005. Archived from the original on 5 March 2005. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 "Blockade From the Seas". Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ "Spectrum". The Tribune. 11 January 2004. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ↑ Singh, Sukhwant (2009). India's Wars Since Independence. Lancer Publishers. p. 480. ISBN 978-1-935501-13-8.

- 1 2 Roy, Mihir K. (1995). War in the Indian Ocean. United States: Lancer Publishers. pp. 218–230. ISBN 978-1-897829-11-0.

- ↑ "Touching Naval Surrender" (PDF). pibarchive.nic.in. 18 December 1971.

- ↑ "Military Losses in the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War". Venik. Archived from the original on 25 February 2002. Retrieved 30 May 2005.

- ↑ Tariq Ali (1983). Can Pakistan Survive? The Death of a State. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-14-022401-6.

- 1 2 3 Staff Report. "Excerpt: How the East was lost: Excerpted with permission from". Dawn Newspapers (Admira's Diary). Dawn Newspapers and Admiral's Diary. Retrieved 21 December 2011.