In computer science, an interchangeability algorithm is a technique used to more efficiently solve constraint satisfaction problems (CSP). A CSP is a mathematical problem in which objects, represented by variables, are subject to constraints on the values of those variables; the goal in a CSP is to assign values to the variables that are consistent with the constraints. If two variables A and B in a CSP may be swapped for each other (that is, A is replaced by B and B is replaced by A) without changing the nature of the problem or its solutions, then A and B are interchangeable variables. Interchangeable variables represent a symmetry of the CSP and by exploiting that symmetry, the search space for solutions to a CSP problem may be reduced. For example, if solutions with A=1 and B=2 have been tried, then by interchange symmetry, solutions with B=1 and A=2 need not be investigated.

The concept of interchangeability and the interchangeability algorithm in constraint satisfaction problems was first introduced by Eugene Freuder in 1991.[1][2] The interchangeability algorithm reduces the search space of backtracking search algorithms, thereby improving the efficiency of NP-complete CSP problems.[3]

Definitions

- Fully Interchangeable

- A value a for variable v is fully interchangeable with value b if and only if every solution in which v = a remains a solution when b is substituted for a and vice versa.[2]

- Neighbourhood Interchangeable

- A value a for variable v is neighbourhood interchangeable with value b if and only if for every constraint on v, the values compatible with v = a are exactly those compatible with v = b.[2]

- Fully Substitutable

- A value a for variable v is fully substitutable with value b if and only if every solution in which v = a remains a solution when b is substituted for a (but not necessarily vice versa).[2]

- Dynamically Interchangeable

- A value a for variable v is dynamically interchangeable for b with respect to a set A of variable assignments if and only if they are fully interchangeable in the subproblem induced by A.[2]

Pseudocode

Neighborhood Interchangeability Algorithm

Finds neighborhood interchangeable values in a CSP. Repeat for each variable:

- Build a discrimination tree by:

- Repeat for each value, v:

- Repeat for each neighboring variable W:

- Repeat for each value w consistent with v:

- Move to if present, construct if not, a node of the discrimination tree corresponding to w|W[2]

- Repeat for each value w consistent with v:

- Repeat for each neighboring variable W:

K-interchangeability algorithm

The algorithm can be used to explicitly find solutions to a constraint satisfaction problem. The algorithm can also be run for k steps as a preprocessor to simplify the subsequent backtrack search.

Finds k-interchangeable values in a CSP. Repeat for each variable:

- Build a discrimination tree by:

- Repeat for each value, v:

- Repeat for each (k − 1)-tuple of variables

- Repeat for each (k − 1)-tuple of values w, which together with v constitute a solution to the subproblem induced by W:

- Move to if present, construct if not, a node of the discrimination tree corresponding to w|W[2]

- Repeat for each (k − 1)-tuple of values w, which together with v constitute a solution to the subproblem induced by W:

- Repeat for each (k − 1)-tuple of variables

Complexity analysis

In the case of neighborhood interchangeable algorithm, if we assign the worst case bound to each loop. Then for n variables, which have at most d values for a variable, then we have a bound of : .

Similarly, the complexity analysis of the k-interchangeability algorithm for a worst case , with -tuples of variables and , for -tuples of values, then the bound is : .

Example

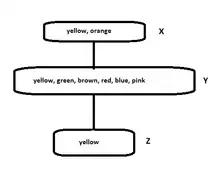

The figure shows a simple graph coloring example with colors as vertices, such that no two vertices which are joined by an edge have the same color. The available colors at each vertex are shown. The colors yellow, green, brown, red, blue, pink represent vertex Y and are fully interchangeable by definition. For example, substituting maroon for green in the solution orange|X (orange for X), green|Y will yield another solution.

Applications

In Computer Science, the interchangeability algorithm has been extensively used in the fields of artificial intelligence, graph coloring problems, abstraction frame-works and solution adaptation.[2][4][5][6] [7][8][9]

References

- ↑ Belaid Benhamou and Mohamed Reda Saidi "Reasoning by dominance in Not-Equals binary constraint networks", Laboratoire des Sciences de l'Information et des Systmes (LSIS),Centre de Mathématiques et d'Informatique, France.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Freuder, E.C.: Eliminating Interchangeable Values in Constraint Satisfaction Problems. In: In Proc. of AAAI-91, Anaheim, CA (1991) 227–233

- ↑ Assef Chmeiss and Lakhdar Sais "About Neighborhood Substitutability in CSP's", University of Artrois, Franc In the meantime, you ce.

- ↑ Haselbock, A.: Exploiting Interchangeabilities in Constraint Satisfaction Problems. In Proc. of the 13 th IJCAI (1993) 282–287

- ↑ Weigel, R., Faltings, B.: Compiling constraint satisfaction problems. Artificial Intelligence 115 (1999) 257–289

- ↑ Choueiry, B.Y.: Abstraction Methods for Resource Allocation. PhD thesis, EPFL PhD Thesis no 1292 (1994)

- ↑ Weigel, R., Faltings, B.: Interchangeability for Case Adaptation in Configura- tion Problems. In Proceedings of the AAAI98 Spring Symposium on Multimodal Reasoning, Stanford, CA, TR SS-98-04. (1998)

- ↑ Neagu, N., Faltings, B.: Exploiting Interchangeabilities for Case Adaptation. In Proc. of the 4th ICCBR01 (2001)

- ↑ Full Dynamic Substitutability by SAT Encoding by Steven Prestwich, Cork Constraint Computation Centre, Department of Computer Science, University College, Cork, Ireland