| Internet |

|---|

|

|

|

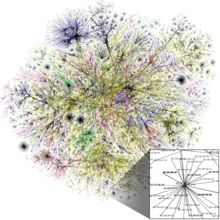

Internet culture is a quasi-underground culture developed and maintained among frequent and active users of the Internet (netizens or digital citizens) who primarily communicate with one another online as members of online communities; that is, a culture whose influence is "mediated by computer screens" and information communication technology,[1]: 63 specifically the Internet.

Internet culture arises from the frequent interactions between members within various online communities and the use of these communities for communication, entertainment, business, and recreation. The earliest online communities of this kind were centered around the interests and hobbies of anonymous and pseudonymous users who were early adopters of the Internet, typically those with academic, technological, highly niche, or even subversive interests. .

The encompassing nature of the Internet culture has led to the study of its many different elements, such as anonymity/pseudonymity, social media, gaming and specific communities, and has also raised questions about online identity and Internet privacy.[2]

Overview

Internet culture is a culture mostly endemic to anonymous or pseudonymous online communities and spaces. Due to the widespread adoption and growing use of the Internet, the impact of Internet culture on predominately offline societies and cultures has been extensive, and elements of Internet culture are increasingly impacting everyday life. Likewise, increasingly widespread adoption of the Internet has influenced Internet culture; frequently provoking fundamental shifts in Internet culture through shaming, censuring and censorship while pressuring other cultural expressions to go underground.[3]

Elements

While Internet subcultures differ, subcultures which emerged in the environment of the early Internet maintain a number of noticeably similar values, which manifest in similar ways.

Macroculture values

Enlightenment principles are prominent values of Internet culture, from which many other elements of the culture are derived.. These principles can be attributed to the Internet's origins as technology developed in a Western, and specifically American, cultural context and the significant influence of academic culture, the hacker ethic and gamer culture, which to varying degrees embrace and amplify cultural values such as curious playfulness, competitiveness and collaborative self-actualization commonly pursued through community application of empirical rationalism via debate, competition and creative expression.

Privacy is another discernable value of Internet culture. Privacy serves to preserve freedom of expression, personal liberty and social equality[4] among peers, thus making anonymity or pseudonymity a valued feature of online services for netizens. This is especially the case for freethinkers, social deviants, political dissidents, journalists, hacktivists/activists and members of hacker, (cyber)punk or other underground subcultures, where an absence of privacy may put an individual in danger. Originally the result of technical limitations of early online systems, the prevalence of anonymity or pseudonymity within online communities such as gaming communities, messageboard/imageboard communities, as well as forum sites and social media has been, and continues to be, an integral part of Internet culture.

Playful curiosity is an additional marker of Internet culture derived from its roots in both creative hacker culture and gamer culture, where a desire to understand complex problems and systems for their own sake, or to exploit for trivial, fun or practically meaningless ends, flourishes.

Learning, technical/mental prowess and disregard of authority are other principles that make their way into Internet culture from its parent subcultures. A value of competence, and thus learning, is introduced through cyberhacker culture, where competence is critical for the successful attainment of objectives; hacker culture, where technical prowess is required to make novel and interesting things; as well as Otaku and gaming cultures, where obsessive commitment and sometimes technical/mental skills are required or encouraged in order to fully engage with, and excel in, deep and time-consuming hobbies. As exemplified in the hacker ethic, social status is largely nonexistent and corresponds only directly with perceived technical competence. For this reason, Internet culture is unconcerned with authority that is not enforced with technical prowess and therefore has a blatant disregard for appeals to authority.

Freedom of information (i.e. sharing and radical transparency) has been argued to be an important quality of the Internet culture.[5]: 7

Manifestations

| "The favorite beverage of the civilised world." |

| —Thomas Jefferson', (February 14, 1824)[6] |

Coffee is more culturally represented than tea in Internet culture, especially within hacking subculture and technical communities.[7] This relates in part to the American origins of the early Internet and its association with enlightenment principles. Coffee's higher caffeine content relative to tea is especially useful for those in technical hacking and technical and creative communities who spend long hours on high-focus tasks. A coffee pot was the subject of the first webcam stream on the Internet and the stream was used to monitor when it was time to make more coffee for the computer science lab that hosted the stream. Automating office coffee production was the subject of an April Fools Internet standard called the Hyper Text Coffee Pot Control Protocol.

Provocative humor that is witty, dry, dark, macabre, self-deprecating, misanthropic and/or politically incorrect is arguably the most recognizable manifestation of Internet culture and its subcultures.[8][9][3] Copypasta, Dank Memes, and Shitposting showcases the culture's emphasis on This humor often includes heavy satire and/or parody of mainstream culture, and the "playful, irreverent attitude" which it inherits from its parent subcultures.

Trolling is another manifestation of Internet culture. With the cultural understanding that absolutely nothing online should be taken seriously, a person's response to Trolling (and not the act of Trolling itself) functions as a shibboleth.[10] [9]

Otaku (sometimes Weeaboo) sensibilities are also found in Internet culture. Much of Internet culture was developed on anonymous imageboards modelled after japanese imageboards that originally hosted, if not featured, anime, manga and other Japanese popular culture materials..

Dissemination and spread

Internet culture and cyberculture spreads through various human interactions; usually mediated by computer networks. These can be activities, pursuits, games, places, and metaphors, and include a diverse base of applications. Some are supported by specialized software and others work on commonly accepted Internet protocols. Examples include but are not limited to:

Internet subcultures

As with other cultures, every element of Internet culture is not exhibited in all individuals exposed to it, and there are many Internet subcultures to which individuals may be exposed.

Due to the use of amplifying curation algorithms on social media platforms, there is growing concern that some emerging Internet subcultures are becoming increasingly radical. It is important to note that not every culture represented on the Internet is an "Internet subculture"; an Internet subculture refers to a culture of users who communicate primarily online.

Early Internet subcultures

Newer Internet subcultures

History

The cultural history of the Internet is a story of rapid change. The Internet developed in parallel with rapid and sustained technological advances in computing and data communication. Widespread access to the Internet emerged as the cost of infrastructure dropped by several orders of magnitude with consecutive technological improvements.

Though Internet culture originated during the creation and development of early online communities – such as those found on bulletin board systems before the Internet reached mainstream adoption in developed countries – many cultural elements have roots in other previously existing offline cultures and subcultures which predate the Internet. Specifically, Internet culture includes many elements of telegraphy culture (especially amateur radio culture), gaming culture and hacker culture.

Initially, digital culture tilted toward the Anglosphere. As a consequence of computer technology's early reliance on textual coding systems that were mainly adapted to the English language, Anglophone societies—followed by other societies with languages based on Latin script—enjoyed privileged access to digital culture. However, other languages have gradually increased in prominence. In specific, the proportion of content on the Internet that is in English has dropped from roughly 80% in the 1990s to around 52.9% in 2018.[11][12]

As technology advances, Internet Culture continues to change. The introduction of smartphones and tablet computers and the growing computer network infrastructure around the world have increased the number of Internet users and have likewise resulted in the proliferation and expansion of online communities. While Internet culture continues to evolve among active and frequent Internet users, it remains distinct from other previously offline cultures and subcultures which now have a presence online, even those cultures and subcultures from which Internet Culture borrows many elements.

One cultural antecedent of Internet culture was amateur radio (commonly known as ham radio). By connecting over great distances, ham operators were able to form a distinct cultural community with a strong technocratic foundation, as the radio gear involved was finicky and prone to failure. The area that later became Silicon Valley, where much of modern Internet technology originates, had been an early locus of radio engineering.[13] Alongside the original mandate for robustness and resiliency, the renegade spirit of the early ham radio community later infused the cultural value of decentralization and near-total rejection of regulation and political control that characterized the Internet's original growth era, with strong undercurrents of the Wild West spirit of the American frontier.

At its inception in the early 1970s as part of ARPANET, digital networks were small, institutional, arcane, and slow, which confined the majority of use to the exchange of textual information, such as interpersonal messages and source code. Access to these networks was largely limited to a technological elite based at a small number of prestigious universities; the original American network connected one computer in Utah with three in California.[14]

Text on these digital networks usually encoded in the ASCII character set, which was minimalistic even for established English typography, barely suited to other European languages sharing a Latin script (but with an additional requirement to support accented characters), and entirely unsuitable to any language not based on a Latin script, such as Mandarin, Arabic, or Hindi.

Interactive use was discouraged except for high value activities. Hence a store and forward architecture was employed for many message systems, functioning more like a post office than modern instant messaging; however, by the standards of postal mail, the system (when it worked) was stunningly fast and cheap. Among the heaviest users were those actively involved in advancing the technology, most of whom implicitly shared much the same base of arcane knowledge, effectively forming a technological priesthood.

The origins of social media predate the Internet proper. The first bulletin board system was created in 1978,[15] GEnie was created by General Electric in 1985[16], the mailing list Listserv appeared in 1986[16], and Internet Relay Chat was created in 1988.[16] The first official social media site, SixDegrees launched in 1997.[16]

In the 1980s, the network grew to encompass most universities and many corporations, especially those involved with technology, including heavy but segregated participation within the American military–industrial complex. Use of interactivity grew, and the user base became less dominated by programmers, computer scientists and hawkish industrialists, but it remained largely an academic culture centered around institutions of higher learning. It was observed that each September, with an intake of new students, standards of productive discourse would plummet until the established user base brought the influx up to speed on cultural etiquette.

Commercial Internet service providers (ISPs) emerged in 1989 in the United States and Australia, opening the door for public participation. Soon the network was no longer dominated by academic culture, and the term eternal September, initially referring to September 1993, was coined as Internet slang for the endless intake of cultural newbies.

Commercial use became established alongside academic and professional use, beginning with a sharp rise in unsolicited commercial e-mail commonly called spam. Around this same time, the network transitioned to support the burgeoning World Wide Web. Multimedia formats such as audio, graphics, and video become commonplace and began to displace plain text, but multimedia remained painfully slow for dial-up users. Also around this time the Internet also began to internationalize, supporting most of the world's major languages, but support for many languages remained patchy and incomplete into the 2010s.

On the arrival of broadband access, file sharing services grew rapidly, especially of digital audio (with a prevalence of bootlegged commercial music) with the arrival of Napster in 1999 and similar projects which effectively catered to music enthusiasts, especially teenagers and young adults, soon becoming established as a prototype for rapid evolution into modern social media. Alongside ongoing challenges to traditional norms of intellectual property, business models of many of the largest Internet corporations evolved into what Shoshana Zuboff terms surveillance capitalism. Not only is social media a novel form of social culture, but also a novel form of economic culture where sharing is frictionless, but personal privacy has become a scarce good.

In 1998, there was Hampster Dance, the first successful Internet meme.[17]

In 1999, Aaron Peckham created Urban Dictionary, an online, crowdsourced dictionary of slang.[17] He had kept the server for Urban Dictionary under his bed.[17]

In 2000, there was great demand for images of a dress that Jennifer Lopez wore. As a result, Google's co-founders created Google Images.[17][18]

In 2001, Wikipedia was created.[17]

In 2004, Encyclopedia Dramatica, a wiki archive of Internet culture, was founded.[19]

In 2005, YouTube was created because people wanted to find videos of Janet Jackson's wardrobe malfunction at the Super Bowl in 2004. YouTube was later acquired by Google in 2006.[17]

In 2009, Bitcoin was created.[17]

Since 2020, Internet culture has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.[20]

Since 2021, there has been an unprecedented surge of interest in the concept of the metaverse.[21][22] In particular, Facebook Inc. renamed itself to Meta Platforms in October 2021, amid the crisis of the Facebook Papers.[23]

Benefits

Social benefits

The creation of the Internet has impacted society greatly, providing the ability to communicate with others online, store information such as files and pictures online, and help expand and maintain government. As the Internet progressed, digital and audio files could be created and shared on the Internet, and became one of the main sources of information, business, and entertainment, leading to the creation of different social media platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and Snapchat.[24] Communicating with others has become easier in the modern day and age, allowing people to connect and interact with each other. The Internet helps people maintain our relationships with others by acting as a supplement to physical interactions with friends and family.[25] People are also able to make forums and talk about different topics with each other which can help form and build relationships. This gives people the ability to express their own views freely. Social groups created on the Internet have also been connected to improving and maintaining health in general. Interacting with social groups online can help prevent and possibly treat depression.[25] In response to the rising prevalence of mental health disorders, including anxiety and depression, a 2019 study by Christo El Morr and others demonstrated that York University students in Toronto were extremely interested in participating in an online mental health support community. The study mentions that many students prefer an anonymous online mental health community to a traditional in person service, due to the social stigmatization of mental health disorders.[26] Overall, online communication with others gives people the sense that they are wanted and are welcomed into social groups.

Criticism

Negative social impacts

From a psychological perspective, electronic and digital culture is highly engrossing. Excessive neglect of the traditional physical and social world in favor of Internet culture became codified as a medical condition under the diagnosis of Internet addiction disorder. With access to the Internet becoming easier for people, it has led to a substantial number of disadvantages. Addiction is a notable issue, as the Internet is becoming increasingly relied on for various everyday tasks.[27] There are a range of different symptoms connected to addiction such as withdrawal, anxiety, and mood swings. Addiction to social media is very prevalent with adolescents, but the interaction they have with one another can be detrimental to their health. This issue requires attention as over 59% of the global population presently utilizes social media, with an average daily usage of 2 hours and 31 minutes, exclusive of other Internet activities.[28] As people spend more time on social media, this could lead to acting excessively and neglecting behaviors. This action may result in the perpetration of cyberbullying, social anxiety, depression, and exposure to inappropriate content that is not suitable for one's age.[29] Rude comments on posts can lower an individual's self-esteem, making them feel unworthy and may lead to depression. Social interaction online may also substitute face-to-face interactions for some people instead of acting as a supplement. This can negatively impact people's social skills and cause one to have feelings of loneliness. People may also face the chance of being cyberbullied when using online applications. Cyberbullying may include harassment, video shaming, impersonating, and much more. A concept described as "cyberbullying theory" is now being used to suggest that children who use social networking more frequently are more likely to become victims of cyberbullying.[30] Additionally, some evidence shows that too much Internet use can stunt memory and attention development in children. The ease of access to information which the Internet provides discourages information retention. However, the cognitive consequences are not yet fully known.[31] The staggering amount of available information online can lead to feelings of information overload. Some effects of this phenomenon include reduced comprehension, decision making, and behavior control.[31]

Identity – "architectures of credibility"

Cyberculture, like culture in general, relies on establishing identity and credibility. However, in the absence of direct physical interaction, it could be argued that the process for such establishment is more difficult.

One early study, conducted from 1998–1999, found that the participants view information obtained online as being slightly more credible than information from magazines, radio, and television. However, the same study found that the participants viewed information obtained from newspapers as the most credible, on average. Finally, this study found that an individual's rate of verification of information obtained online was low, and perhaps over reported depending on the type of information.[32]

How does cyberculture rely on and establish identity and credibility? This relationship is two-way, with identity and credibility being both used to define the community in cyberspace and to be created within and by online communities.

In some senses, online credibility is established in much the same way that it is established in the offline world; however, since these are two separate worlds, it is not surprising that there are differences in their mechanisms and interactions of the markers found in each.

Following the model put forth by Lawrence Lessig in Code: Version 2.0,[33] the architecture of a given online community may be the single most important factor regulating the establishment of credibility within online communities. Some factors may be:

- Anonymous versus Known

- Linked to Physical Identity versus Internet-based Identity Only

- Unrated Commentary System versus Rated Commentary System

- Positive Feedback-oriented versus Mixed Feedback (positive and negative) oriented

- Moderated versus Unmoderated

Anonymous versus known

Many sites allow anonymous commentary, where the user-id attached to the comment is something like "guest" or "anonymous user". In an architecture that allows anonymous posting about other works, the credibility being impacted is only that of the product for sale, the original opinion expressed, the code written, the video, or other entity about which comments are made (e.g., a Slashdot post). Sites that require "known" postings can vary widely from simply requiring some kind of name to be associated with the comment to requiring registration, wherein the identity of the registrant is visible to other readers of the comment. These "known" identities allow and even require commentators to be aware of their own credibility, based on the fact that other users will associate particular content and styles with their identity. By definition, then, all blog postings are "known" in that the blog exists in a consistently defined virtual location, which helps to establish an identity, around which credibility can gather. Conversely, anonymous postings are inherently incredible. Note that a "known" identity need have nothing to do with a given identity in the physical world.

Linked to physical identity versus Internet-based identity only

Architectures can require that physical identity be associated with commentary, as in Lessig's example of Counsel Connect.[33]: 94–97 However, to require linkage to physical identity, many more steps must be taken (collecting and storing sensitive information about a user) and safeguards for that collected information must be established-the users must have more trust of the sites collecting the information (yet another form of credibility). Irrespective of safeguards, as with Counsel Connect,[33]: 94–97 using physical identities links credibility across the frames of the Internet and real space, influencing the behaviors of those who contribute in those spaces. However, even purely Internet-based identities have credibility. Just as Lessig describes linkage to a character or a particular online gaming environment, nothing inherently links a person or group to their Internet-based persona, but credibility (similar to "characters") is "earned rather than bought, and because this takes time and (credibility is) not fungible, it becomes increasingly hard" to create a new persona.[33]: 113

Unrated commentary system versus rated commentary system

In some architectures, those who review or offer comments can, in turn, be rated by other users. This technique offers the ability to regulate the credibility of given authors by subjecting their comments to direct "quantifiable" approval ratings.

Positive feedback-oriented versus mixed feedback (positive and negative) oriented

Architectures can be oriented around positive feedback or a mix of both positive and negative feedback. While a particular user may be able to equate fewer stars with a "negative" rating, the semantic difference is potentially important. The ability to actively rate an entity negatively may violate laws or norms that are important in the jurisdiction in which the Internet property is important. The more public a site, the more important this concern may be, as noted by Goldsmith & Wu regarding eBay.[34]

Moderated versus unmoderated

Architectures can also be oriented to give editorial control to a group or individual. Many email lists are worked in this fashion (e.g., Freecycle). In these situations, the architecture usually allows, but does not require that contributions be moderated. Further, moderation may take two different forms: reactive or proactive. In the reactive mode, an editor removes posts, reviews, or content that is deemed offensive after it has been placed on the site or list. In the proactive mode, an editor must review all contributions before they are made public.

In a moderated setting, credibility is often given to the moderator. However, that credibility can be damaged by appearing to edit in a heavy-handed way, whether reactive or proactive (as experienced by digg.com). In an unmoderated setting, credibility lies with the contributors alone. The very existence of an architecture allowing moderation may lend credibility to the forum being used (as in Howard Rheingold's examples from the WELL),[1] or it may take away credibility (as in corporate web sites that post feedback, but edit it highly).

Digital culture

Memes and viral phenomena

Internet culture is characterized by the prevalence of memes, viral videos, challenges, and trends that rapidly spread across online platforms. Memes, which are humorous or satirical images, videos, or text, often undergo slight variations as they are shared and replicated. Notable examples of memes include the "Distracted Boyfriend" meme and the "Harlem Shake" viral videos. These memes reflect the cultural references and humor prevalent in online communities.

Online communities and subcultures

Internet culture thrives on various online communities and subcultures that foster shared interests and interactions. These communities can be found on platforms like Reddit, forums, or dedicated social media groups. They cater to specific hobbies, fandoms, or professions, creating spaces where individuals with similar interests can connect. Examples of such communities include the passionate "K-pop fandom" or the enthusiastic "tech enthusiast groups."

Internet slang and jargon

Online communication within internet culture has given rise to a distinct set of slang, acronyms, and jargon. These terms often evolve rapidly and serve as concise and recognizable ways to convey ideas or foster a sense of belonging within online communities. Common examples of internet slang and jargon include "LOL" (laugh out loud), "FTW" (for the win), and "AFK" (away from keyboard).

Online gaming culture

Online gaming has become an integral part of internet culture, with dedicated communities, esports, and streaming platforms like Twitch. Competitive gaming has seen significant growth, and live streaming has revolutionized the way viewers engage with gaming content. Online gaming culture encompasses various subcultures shaped by influential games, events, and players, contributing to the vibrant landscape of internet culture.

Social media and influencers

The rise of social media platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok has had a profound impact on internet culture. These platforms have given rise to influencers, content creators, and online celebrities. Influencers play a crucial role in shaping trends, promoting products, and engaging with their audiences. However, the influencer culture is not without challenges and controversies.

Internet activism and online movements

Internet culture has become an instrumental platform for activism and social movements. Hashtags, online petitions, and digital organizing have facilitated the rapid spread of awareness, advocacy, and mobilization. Significant movements like #BlackLivesMatter or #MeToo have originated online and have had a substantial impact on offline activism, demonstrating the power of internet culture in driving societal change.

Relationship with "cyberculture"

Internet culture as a cyberculture

First and foremost, cyberculture derives from traditional notions of culture, as the roots of the word imply. In non-cyberculture, it would be odd to speak of a single, monolithic culture. In cyberculture, by extension, searching for a single thing that is cyberculture would likely be problematic. The notion that there is a single, definable cyberculture is likely the complete dominance of early cyber territory by affluent North Americans. Writing by early proponents of cyberspace tends to reflect this assumption (see Howard Rheingold).[1]

The ethnography of cyberspace is an important aspect of cyberculture that does not reflect a single unified culture. It "is not a monolithic or placeless 'cyberspace'; rather, it is numerous new technologies and capabilities, used by diverse people, in diverse real-world locations." It is malleable, perishable, and can be shaped by the vagaries of external forces on its users. For example, the laws of physical world governments, social norms, the architecture of cyberspace, and market forces shape the way cybercultures form and evolve. As with physical world cultures, cybercultures lend themselves to identification and study.

There are several qualities that cybercultures share that make them warrant the prefix "cyber-". Some of those qualities are that cyberculture:

- Is a community mediated by Information Communication Technologies.

- Is culture "mediated by computer screens".[1]: 63

- Relies heavily on the notion of information and knowledge exchange.

- Depends on the ability to manipulate tools to a degree not present in other forms of culture (even artisan culture, e.g., a glass-blowing culture).

- Allows vastly expanded weak ties and has been criticized for overly emphasizing the same (see Bowling Alone and other works).

- Multiplies the number of eyeballs on a given problem, beyond that which would be possible using traditional means, given physical, geographic, and temporal constraints.

- Is a "cognitive and social culture, not a geographic one".[1]: 61

- Is "the product of like-minded people finding a common 'place' to interact."[35]: 58

- Is inherently more "fragile" than traditional forms of community and culture (John C. Dvorak).

Thus, cyberculture can be generally defined as the set of technologies (material and intellectual), practices, attitudes, modes of thought, and values that developed with cyberspace.[36]

| The Internet is one gigantic well-stocked fridge ready for raiding; for some strange reason, people go up there and just give stuff away. |

| —Mega 'Zines, Macworld (1995)[37] |

Since the boundaries of cyberculture are difficult to define, the term is used flexibly, and its application to specific circumstances can be controversial. It generally refers at least to the cultures of virtual communities, but can also extend to a wide range of cultural issues relating to "cyber-topics", e.g. cybernetics, and the perceived or predicted cyborgization of the human body and human society itself. It can also embrace associated intellectual and cultural movements, such as cyborg theory and cyberpunk. The term often incorporates an implicit anticipation of the future.

The Oxford English Dictionary lists the earliest usage of the term "cyberculture" in 1963, when Alice Mary Hilton wrote the following, "In the era of cyberculture, all the plows pull themselves and the fried chickens fly right onto our plates."[38] This example, and all others, up through 1995 are used to support the definition of cyberculture as "the social conditions brought about by automation and computerization."[38] The American Heritage Dictionary broadens the sense in which "cyberculture" is used by defining it as, "The culture arising from the use of computer networks, as for communication, entertainment, work, and business".[39] However, both OED and the American Heritage Dictionary fail to describe cyberculture as a culture within and among users of computer networks. This cyberculture may be purely an online culture or it may span both virtual and physical worlds. This is to say, that cyberculture is a culture endemic to online communities; it is not just the culture that results from computer use, but culture that is directly mediated by the computer. Another way to envision cyberculture is as the electronically enabled linkage of like-minded, but potentially geographically disparate (or physically disabled and hence less mobile) persons. Cyberculture is a wide social and cultural movement closely linked to advanced information science and information technology, their emergence, development and rise to social and cultural prominence between the 1960s and the 1990s. Cyberculture was influenced by those early users of the Internet, frequently including the architects of the original project. These individuals were often guided in their actions by the hacker ethic. While early cyberculture was based on a small cultural sample, and its ideals, the modern cyberculture is a much more diverse group of users and the ideals that they espouse.

Numerous specific concepts of cyberculture have been formulated by such authors as Lev Manovich,[40][41] Arturo Escobar and Fred Forest.[42] However, most of these concepts given by these authors focus only on certain aspects, and they do not cover these in great detail. Some authors aim to achieve a more comprehensive understanding distinguished between early and contemporary cyberculture (Jakub Macek),[43] or between cyberculture as the cultural context of information technology and cyberculture (more specifically cyberculture studies) as "a particular approach to the study of the 'culture + technology' complex" (David Lister et al.).[44]

Cyberculture studies

The field of cyberculture studies examines the topics explained above, including the communities emerging within the networked spaces sustained by the use of modern technology. Students of cyberculture engage with political, philosophical, sociological, and psychological issues that arise from the networked interactions of human beings by humans who act in various relations to information science and technology.

Donna Haraway, Sadie Plant, Manuel De Landa, Bruce Sterling, Kevin Kelly, Wolfgang Schirmacher, Pierre Levy, David Gunkel, Victor J.Vitanza, Gregory Ulmer, Charles D. Laughlin, and Jean Baudrillard are among the key theorists and critics who have produced relevant work that speaks to, or has influenced studies in, cyberculture. Following the lead of Rob Kitchin, in his work Cyberspace: The World in the Wires, cyberculture might be viewed from different critical perspectives. These perspectives include futurism or techno-utopianism, technological determinism, social constructionism, postmodernism, poststructuralism, and feminist theory.[35]: 56–72

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rheingold, Howard (1993). "Daily Life in Cyberspace". The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-097641-1.

- ↑ Silver, David (February 2004). "Internet/Cyberculture/ Digital Culture/New Media/ Fill-in-the-Blank Studies". New Media & Society. 6 (1): 55–64. doi:10.1177/1461444804039915. ISSN 1461-4448. S2CID 32041186. Archived from the original on 2020-09-03. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- 1 2 Phillips, Whitney (2019). "It Wasn't Just the Trolls: Early Internet Culture, "Fun," and the Fires of Exclusionary Laughter". Social Media + Society. 5 (3). doi:10.1177/2056305119849493. S2CID 199164695.

- ↑ "Pool's Closed". www.knowyourmeme.com. 11 April 2009. Archived from the original on 2020-07-20. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ↑ Dariusz Jemielniak; Aleksandra Przegalinska (18 February 2020). Collaborative Society. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-35645-9. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ↑ Coffee https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thomas-jefferson-encyclopedia/coffee/#fn-1 Archived 2023-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "418 – I'm a teapot". www.slate.com. Archived from the original on 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ↑ Giselinde Kuipers, "Good Humor, Bad Taste: A Sociology of the Joke", ISBN 1501510894, 2015, pp.41, 42

- 1 2 Phillips, Whitney (21 May 2015). "RIP Trolling – How the internet has transformed dark humor". Slate. Archived from the original on 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ↑ "Consider the Troll". www.popmatters.com. 26 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ↑ "The digital language divide". labs.theguardian.com. Archived from the original on 2022-05-27. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ↑ "Chart of the day: The Internet has a language diversity problem". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 2022-05-11. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ↑ Abate, Tom (29 September 2007). "High-tech culture of Silicon Valley originally formed around radio". SF Gate. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ↑ Markoff, John (1999-12-20). "An Internet Pioneer Ponders the Next Revolution". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2008-09-22. Retrieved 2023-03-08.https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/tech/99/12/biztech/articles/122099outlook-bobb.html Archived 2008-09-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Edwards, Benj (2016-11-04). "The Lost Civilization of Dial-Up Bulletin Board Systems". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2021-12-06. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- 1 2 3 4 Allebach, Nathan (2020-07-31). "A Brief History of Internet Culture and How Everything Became Absurd". The Startup. Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Friedman, Linda Weiser; Friedman, Hershey H. (2015-07-09). "Connectivity and Convergence: A Whimsical History of Internet Culture". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2628901.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Google It! Jennifer Lopez Wears That Grammys Dress—The One That Broke the Internet—20 Years Later at Versace". Vogue. 2019-09-20. Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia Dramatica – Know Your Meme". Know Your Meme. 2022-02-01. Archived from the original on 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ↑ "COVID-19 changed global Internet culture, says app maker". Punch Newspapers. 2022-02-01. Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- ↑ "Google Trends". Google Trends. Archived from the original on 2022-02-03. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- ↑ "Framework for the Metaverse". MatthewBall.vc. Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- ↑ "In the middle of a crisis, Facebook Inc. renames itself Meta". AP NEWS. 2021-10-28. Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- ↑ Kompare, Derek (2019-10-31). "Media Studies and the Internet". Journal of Cinema and Media Studies. 59 (1): 134–141. doi:10.1353/cj.2019.0072. ISSN 2578-4919. S2CID 211774929. Archived from the original on 2020-10-01. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- 1 2 Pendry, Louise F.; Salvatore, Jessica (2015-09-01). "Individual and social benefits of online discussion forums". Computers in Human Behavior. 50: 211–220. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.067. hdl:10871/16948. ISSN 0747-5632.

- ↑ El Morr, Christo; Maule, Catherine; Ashfaq, Iqra; Ritvo, Paul; Ahmad, Farah (September 2020). "Design of a Mindfulness Virtual Community: A focus-group analysis". Health Informatics Journal. 26 (3): 1560–1576. doi:10.1177/1460458219884840. ISSN 1460-4582. PMID 31709878. S2CID 207944912.

- ↑ Chen, Leida; Nath, Ravi (2016-05-01). "Understanding the underlying factors of Internet addiction across cultures: A comparison study". Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 17: 38–48. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2016.02.003. ISSN 1567-4223.

- ↑ Chaffey, Dave (2023-01-30). "Global social media statistics research summary 2022 [June 2022]". Smart Insights. Archived from the original on 2022-09-27. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- ↑ "Pros and Cons of Social Media". Lifespan. Archived from the original on 2023-05-04. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- ↑ McDool, Emily; Powell, Philip; Roberts, Jennifer; Taylor, Karl (2020-01-01). "The internet and children's psychological wellbeing". Journal of Health Economics. 69: 102274. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.102274. ISSN 0167-6296. PMID 31887480.

- 1 2 Union, Publications Office of the European (2020-08-13). Potential negative effects of internet use : in-depth analysis. European Parliament. ISBN 9789284664610. Archived from the original on 2021-01-02. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Flanagin, Andrew J.; Metzger, Miriam J. (September 2000). "Perceptions of Internet Information Credibility". Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 77 (3): 515–540. doi:10.1177/107769900007700304. ISSN 1077-6990. S2CID 15996706. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- 1 2 3 4 Lessig, Lawrence (2006). Code 2.0: Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03914-2.

- ↑ Goldsmith, Jack; Wu, Tim (2006). Who Controls the Internet? Illusions of a Borderless World. Oxford University Press (US). p. 143. ISBN 0-19-515266-2.

- 1 2 Kitchin, Rob (1998). "Theoretical Perspective: Approaching Cyberspace". Cyberspace: The World in the Wires. New York: Wiley.

- ↑ Lévy, Pierre (2001). Cyberculture (Electronic Mediations). University of Minnesota Press.

- ↑ Pogue, David (May 1995). "Mega 'Zines: Electronic Mac Mags make modems meaningful". Macworld: 143–144.

The internet is one gigantic well-stocked fridge ready for raiding; for some strange reason, people go up there and just give stuff away.

- 1 2 "cyberculture, n". OED online. Oxford University Press. December 2001.

- ↑ "cyberculture, n". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2000.

- ↑ Manovich, Lev (2003). "New Media from Borges to HTML" (PDF). In Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Nick Montfort (ed.). The New Media Reader. MIT Press. pp. 13–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ↑ Manovich, Lev (2001). The Language of a New Media. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-63255-1.

- ↑ Forest, Fred, Pour un art actuel, l'art à l'heure d'Internet, archived from the original on 2013-07-02, retrieved 2008-02-15

- ↑ Macek, Jakub (2005), Defining Cyberculture (v. 2), translated by Metyková, Monika; Macek, Jakub, archived from the original on 2012-02-25, retrieved 2007-02-15

- ↑ Lister, David; Jon Dovey; Seth Giddings; Iain Grant; Kieran Kelly (2003). New Media: A Critical Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22378-4.

Further reading

- David Gunkel (2001) Hacking Cyberspace, Westview Press, ISBN 0-8133-3669-4

- Clemens Apprich (2017) Technotopia: A Media Genealogy of Net Cultures, Rowman & Littlefield International, London ISBN 978-1786603142

- Sandrine Baranski (2010) La musique en réseau, une musique de la complexité ?, Éditions universitaires européennes La musique en réseau

- David J. Bell, Brian D Loader, Nicholas Pleace, Douglas Schuler (2004) Cyberculture: The Key Concepts, Routledge: London.

- Donna Haraway (1991) Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, Routledge, New York, NY

- Donna Haraway (1997) Modest Witness Second Millennium FemaleMan Meets OncoMouse, Routledge, New York, NY

- N. Katherine Hayles (1999) How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics, Chicago University Press, Chicago, IL

- Jarzombek, Mark (2016) Digital Stockholm Syndrome in the Post-Ontological Age, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN

- Paasonen, Susanna (2005). Figures of fantasy: Internet, women, and cyberdiscourse. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-7607-0.

- Sherry Turkle (1997) Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet, Simon & Schuster Inc, New York, NY

- Marwick, Alice E. (2008). "Becoming Elite: Social Status in Web 2.0 Cultures" (PDF). Dissertation. Department of Media, Culture, and Communication New York University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- Haraway, Donna (1991). "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century". Archived from the original on 2012-02-14. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hayles, N. Katherine (Fall 1993). "Virtual Bodies and Flickering Signifiers". Archived from the original on 2009-03-17. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)