Several aviators have been claimed to be the first to fly a powered aeroplane. Much controversy surrounds these claims. It is generally accepted today that the Wright brothers were the first to achieve sustained and controlled powered manned flight, in 1903. It is popularly held in Brazil that their native citizen Alberto Santos-Dumont was the first successful aviator, discounting the Wright brothers' claim because their Flyer took off from a rail, and in later flights would sometimes employ a catapult. An editorial in the 2013 edition of Jane's All the World's Aircraft supported the claim of Gustave Whitehead. Claims by, or on behalf of, other pioneers such as Clement Ader have also been put forward from time to time.

Significant claims

Several aviators or their supporters have laid claim to the first manned flight in a powered aeroplane. Claims that have received significant attention include:

- Clément Ader in the Avion III (1897)

- Gustave Whitehead in his No's. 21 and 22 aeroplanes (1901–1903)

- Richard Pearse in his monoplane (1903–1904)

- Samuel Pierpont Langley's Aerodrome A (1903)

- Karl Jatho in Jatho biplane (1903)

- The Wright brothers in the Wright Flyer (1903)

- Alberto Santos-Dumont in the 14-bis (1906)

In judging these claims, the generally accepted requirements are for sustained powered and controlled flight. In 1890 Ader had made a brief uncontrolled and unsustained "hop" in his Éole, but such a hop is not regarded as true flight. The ability to take off unaided is also sometimes regarded as necessary, while the minimum necessary distance flown to qualify has been the subject of contention. Air historian Charles Gibbs-Smith has said that, "The criteria of powered flight must remain to some extent a matter of opinion."[1] Mythical or entirely fictional claims are not considered here.

History

Antecedents

Some notable powered hops were made before the problem of powered flight was finally solved.

In 1874 Félix du Temple built a steam-powered aeroplane which took off from a ramp with a sailor on board and remained airborne for a short distance. This has sometimes been claimed as the first powered flight in history but the claim is generally rejected because takeoff was gravity-assisted and flight was not sustained. It is however credited as the first powered takeoff in history.[2][3]

Ten years later in 1884 the Russian Alexander Mozhaysky achieved similar success, launching his craft from a ramp and remaining airborne for 30 m (98 ft). The claim that this was a sustained flight has not been taken seriously outside Russia.[2]

Clément Ader's Éole of 1890 was a bat-winged tractor monoplane which achieved a brief, uncontrolled hop, becoming the first heavier-than-air machine in history to take off from level ground under its own power.[2] However his hop is not regarded as true flight because it was neither sustained nor controlled. Ader would later make a controversial claim of a more extended flight.[2]

The 1901 Drachenflieger of Wilhelm Kress was a triple-tandem winged floatplane. It had been inspired by Samuel Pierpoint Langley's experiments and, like his later designs, was powered by an internal combustion engine. It demonstrated good control when taxiing, but was too underpowered and failed to take off.[2]

The period of claimed flights

.jpg.webp)

Few of the claims to powered flight were widely accepted, or even made, at the time the events took place. Both the Wrights and Whitehead suffered in their early years from a lack of general recognition, while neither Ader nor Langley made any claim in the years immediately following their work. Indeed, Langley died in 1906 without ever making any claim of success.

The pioneer Octave Chanute promoted the Wrights' work, some of which he witnessed, in the United States and Europe. The brothers began to gain recognition in Britain, where Colonel John Edward Capper was taking charge of Army aeronautical work. On a visit to the U.S. in 1904 Capper befriended the Wrights and subsequently helped foster their early recognition. He also visited Langley, who openly discussed his failure with Capper.[5]

In 1906 the U.S. Army rejected a proposal from the Wrights on the basis that their machine's ability to fly had not been demonstrated. Thus, when Alberto Santos-Dumont made a brief flight that year in his 14-bis aeroplane, there was no acknowledged antecedent and he was acclaimed in France and elsewhere as the first to fly. Ader responded by claiming that he had flown in his Avion III back in 1897.[2]

Claims and recognition

Santos-Dumont's 1906 claim to flight has never been seriously disputed, although few authorities credit his as the first, while some have questioned the effectiveness of his controls.[6]

In 1908 the Wrights embarked on a series of demonstrations with their by now much improved Flyers, Orville in America and Wilbur in Europe.

Ader's claim was debunked in 1910, when the official report on his work was finally published.[2]

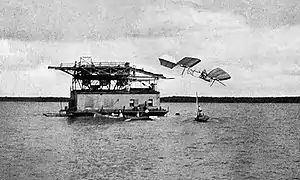

In the United States, the Smithsonian Institution, and primarily its then-Secretary Charles Walcott, refused to give credit to the Wright Brothers for the first powered, controlled flight of an aircraft. Instead, they honored the former Smithsonian Secretary Samuel Pierpont Langley, whose 1903 tests of his Aerodrome on the Potomac were not successful. In 1914, Glenn Curtiss had recently exhausted the appeal process in a patent infringement legal battle with the Wrights. Curtiss sought to prove Langley's machine, which failed piloted tests nine days before the Wrights' successful flight in 1903, capable of controlled, piloted flight in an attempt to invalidate the Wrights' wide-sweeping patents.

The Aerodrome was removed from exhibit at the Smithsonian and prepared for flight at Keuka Lake, New York. Curtiss called the preparations "restoration" claiming that the only addition to the design was pontoons to support testing on the lake but critics including patent attorney Griffith Brewer called them alterations of the original design. Curtiss flew the modified Aerodrome, hopping a few feet off the surface of the lake for 5 seconds at a time.[7]

They used this as the basis for a claim that the Aerodrome was the first aeroplane "capable of flight". Orville, the surviving Wright brother, began a long and bitter public relations battle to force it to recognize their claim to primacy, his disgust reaching such a peak that in 1928 he sent the historic Flyer for display in the British Science Museum in London. He eventually succeeded in his battle, in 1942, when the Smithsonian, under a new Secretary Charles Abbot, admitted to Curtiss' modifications and withdrew its claim.[8][9]

Meanwhile, with the publication of a co-authored article and a book by the journalist Stella Randolph, Whitehead had also begun to gain vocal advocates. In 1945 Orville Wright issued a critique of the evidence for Whitehead.[10]

Orville died on January 30, 1948. As part of the Smithsonian's final deal with his executors, the Flyer was returned to the United States and put on display. A clause in the contract required the Smithsonian to claim primacy for the Wrights, on pain of losing the prize exhibit.[11]

Whitehead's advocates have fought an equally bitter battle with the Smithsonian in an attempt to gain recognition, in which the Smithsonian's contract with the Wright estate has been subject to heavy criticism. Although Whitehead's advocates have gained some following, they remain in the minority.[12] [13]

It is generally accepted today that the Wright brothers were the first to make sustained and controlled heavier-than-air powered flights. Many in Brazil regard Santos-Dumont as the first successful aviator because his craft did not use an external launch system.[14] [15]

Ader

.jpg.webp)

Following his hop in the Éole, Clément Ader obtained funding from the French Ministry for War. He built two more machines; the 'Avion II and in 1897 the similar but larger Avion III. Neither was able to leave the ground at all.[2]

Several years later in 1906, following Blériot's first successful flights Ader claimed publicly that his Éole had flown for 330 ft (100 m) in 1891, and that the Avion III had flown for 1,000 ft on the second day of its trials.[2]

Ader's claim for the Avion III was refuted four years later in 1910, when the French Ministry for War finally published its report on his work.[2] His claim for the Éole also collapsed through lack of credibility.[2]

Whitehead

When Gustav Weisskopf immigrated to the United States he changed his name to Gustave Whitehead. There he began an extensive series of experiments with gliders, aero engines and motorized flying machines. Whitehead and other sources have claimed he made successful powered aeroplane flights.

- Louis Darvarich, a friend of Whitehead, said they flew together in a steam-powered machine in 1899 and crashed into the side of a building in their path.[10]

- The Bridgeport Herald newspaper reported that on August 14, 1901, Whitehead flew his No. 21 monoplane to a height of 50 ft (15 m) and could steer it a little by shifting his weight to the left or right.[10]

- Whitehead wrote letters to a magazine, saying that in 1902 he made two flights in his No. 22 machine, including a circle, steering with a combination of the rudder and variable speeds of the two propellers.[10]

Controversy ignites

Stanley Beach was a friend of Whitehead, sharing a patent application with him in 1905. Beach's father was editor of Scientific American, which was initially sympathetic to Whitehead and included a number of reports of short flights by Whitehead.[16][17][18][19][20] Later, Beach and Whitehead fell out and, now editor of the Scientific American in his turn, Beach denied that Whitehead ever flew.[21]

Whitehead's claims were not taken seriously until two journalists, Stella Randolph and Harvey Phillips, wrote an article in a 1935 edition of Popular Aviation journal. Harvard University economics professor John B. Crane responded with a rebuttal, published in National Aeronautic Magazine in December 1936. The next year Randolph expanded the article, together with additional research, into a book titled Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead. Crane changed his mind in 1938 and suggested that a Congressional investigation should consider the claims. By 1945 Orville Wright was sufficiently concerned about the Whitehead claims that he issued his own rebuttal in US Air Services.[10] Then in 1949 Crane published a new article in Air Affairs magazine that supported Whitehead.

O'Dwyer and Randolph claims

Following a chance discovery in 1963, reserve U.S. Air Force major William O'Dwyer was asked to research Whitehead's claims. He became convinced that Whitehead did fly and contributed research material to a second book by Stella Randolph, The Story of Gustave Whitehead, Before the Wrights Flew, published in 1966.[22][23]

O'Dwyer and Randolph co-authored another book, History by Contract, published in 1978. The book criticised the Smithsonian Institution for its contracted obligation to credit only the 1903 Wright Flyer for the first powered controlled flight, claiming that it created a conflict of interest and had been kept secret. The Smithsonian defended itself vigorously.

Jane's renews controversy

On March 8, 2013, the aviation annual Jane's All the World's Aircraft published an editorial by Paul Jackson endorsing the Whitehead claim.[24] Jackson's editorial drew heavily upon information provided by aviation researcher John Brown, whom he complimented for his work. Brown had begun researching Whitehead's aircraft while working as a contractor for the Smithsonian. Jane's corporate owner later distanced itself from the editorial, stating it contained the views of the editor, not the publisher.[25][26]

Brown analysed a vintage photograph of an early indoor aeronautical exhibition, claiming that an even earlier photograph visible on the wall showed the Whitehead No. 21 aircraft in powered flight. Jackson's editorial did not mention the claim, and two weeks after its publication he stated to the press that the image was not significant to the claim of Whitehead's flight, remarking, "And that entirely spurious 'Where's the photograph?' argument." Aviation historian Carroll Gray subsequently identified the photo seen on the wall "beyond any reasonable doubt" as a glider built and displayed in California by aviation pioneer John J. Montgomery.[27]

Responding to the renewed controversy, Tom Crouch, a senior curator at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, formally acknowledged the Wright contract, saying that it had never been a secret.[11] He also stated;

I can only hope that, should persuasive evidence for a prior flight be presented, my colleagues and I would have the courage and the honesty to admit the new evidence and risk the loss of the Wright Flyer.

— Tom Crouch, The Wright-Smithsonian Contract, [11]

Scientific American published a rebuttal of the Whitehead claims written by its senior copy editor Daniel C. Schlenoff, who asserted, regarding the Bridgeport Herald report, that "The consensus on the article is that it was an interesting work of fiction."[28]

Thirty-eight air historians and journalists also responded to the revived controversy with a "Statement Regarding The Gustave Whitehead Claims of Flight", rejecting the evidence supporting the claims and noting that, "When it comes to the case of Gustave Whitehead, the decision must remain, not proven."[29]

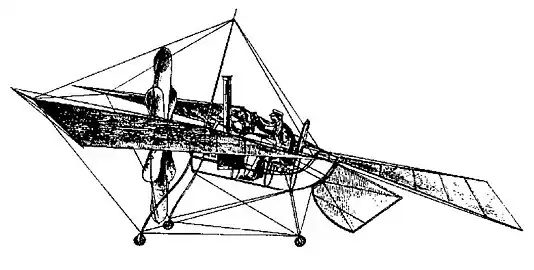

Langley

Samuel Pierpont Langley was secretary to the Smithsonian Institution from 1887 until the year of his death in 1906. During this period, and in due course supported by the United States War Department, he conducted aeronautical experiments, culminating in his manned Aerodrome A. Under Langley's instruction Charles M. Manly attempted to fly the craft from a catapult on the roof of a houseboat in 1903. Two attempts, on October 7 and December 8, both failed with Manly receiving a soaking each time.[2]

Glenn Curtiss and the Smithsonian

Some ten years later in 1914 Glenn Curtiss modified the Aerodrome and flew it a few hundred feet, as part of his attempt to fight a patent owned by the Wright brothers, and as an effort by the Smithsonian to rescue Langley's aeronautical reputation. The Curtiss flights emboldened the Smithsonian to display the Aerodrome in its museum as "the first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight". Fred Howard, extensively documenting the controversy, wrote: "It was a lie pure and simple, but it bore the imprimatur of the venerable Smithsonian and over the years would find its way into magazines, history books, and encyclopedias, much to the annoyance of those familiar with the facts."[30]

The Smithsonian's action triggered a decades-long feud with the surviving Wright brother, Orville. It was not until 1942 that the Smithsonian finally relented, publishing the Aerodrome modifications made by Curtiss and recanting misleading statements it had made about the 1914 tests.[9]

Wrights

On December 17, 1903, a few miles south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the Wright brothers launched their aeroplane from a dolly running along a short rail, which was laid on level ground. Taking turns, Orville and Wilbur made four brief flights at an altitude of about ten feet each time. The flight paths were all essentially straight; turns were not attempted. Each flight ended in a bumpy and unintended "landing" on the undercarriage skids or runners, as the craft did not have wheels. The last flight, by Wilbur, was 852 feet (260 m) in 59 seconds, much longer than each of the three previous flights of 120, 175 and 200 feet. The Flyer moved forward under its own engine power and was not assisted by catapult, a device the brothers did use during flight tests in the next two years and at public demonstrations in the U.S. and Europe in 1908–1909. A headwind averaging about 20 mph gave the machine sufficient airspeed to become airborne; its speed over the ground was less than 10 mph. Photographs were taken of the machine in flight.

The Wrights kept detailed logs and diaries about their work.[31][32][33][34] Their correspondence with Octave Chanute provides a virtual history of their efforts to invent a flying machine. They also documented their work in photographs, although they did not make public any photos of their powered flights until 1908. Their written records also were not made available to the public at the time, though they were published in 1953 after the Wright estate donated them to the U.S. Library of Congress.[35]

The Wrights' claim to a historic first flight was largely accepted by U.S. newspapers but inaccurately reported initially. In January 1904 they issued a statement to newspapers accurately describing the flights. After an announced public demonstration in May 1904 in Dayton, the Wrights made no further effort to publicize their work, and were advised by their patent attorney to keep details of their machine confidential. In 1905 a few dozen people witnessed flights by the Wright Flyer III. Pioneers such as Octave Chanute and the British Army officer Lt. Col. John Capper were among those who believed the Wrights' public and private statements about their flights.[5]

In 1906, almost three years after the first flights, the U.S. Army rejected an approach from the Wrights on the basis that their proposed machine's ability to fly had not been demonstrated.[5]

By 1907 the Wrights' claims were accepted widely enough for them to be in negotiations with Britain, France and Germany as well as their own government, and early in 1908 they concluded contracts with both the US War Department and a French syndicate. In May Wilbur sailed for Europe in order to carry out acceptance trials for the French contract. On 4 July 1908 Glenn Curtiss gave the first widely publicised public demonstration of flight in the USA. As a result, the Wright brothers' prestige fell. Subsequent flights of both brothers that year went on to astonish the world and their early claims gained almost universal public recognition as legitimate.[5]

Subsequent criticisms of the Wrights have included accusations of secrecy before coming to Europe in 1908, the use of a catapult-assisted launch,[36] and such a lack of aerodynamic stability as to make the machine almost unflyable.

The Smithsonian feud

Following the Curtiss experiments with the Langley Aerodrome in 1914, surviving Wright brother Orville began a long and bitter campaign against the Smithsonian to gain recognition. His disgust reached such a peak in 1928 that he sent the historic Flyer for display in the British Science Museum in London.[37] It was not until 1942 that the Smithsonian finally relented, at last retracting its claims for Langley and acknowledging the Wrights' place in history.[9]

Orville died on January 30, 1948. The Flyer – delayed by the war and an arrangement for a copy to be made – was returned to its native America and put on display in the Smithsonian. A clause in the contract required the Smithsonian to claim primacy for the Wrights, at risk of losing their newly acquired prize exhibit. The Smithsonian has honoured its contract ever since and continues to support the Wrights' claim.[11]

Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont was a Brazilian aviation pioneer of French ancestry. Having immigrated to France for studies, he made his aeronautical name in that country with airships before turning to heavier-than-air flight. On 23 October 1906 he flew his 14-bis biplane for a distance of 60 metres (200 feet) at a height of about five meters or less (15 ft).[1] The flight was officially observed and verified by the Aéro-Club (later renamed the Aéro-Club de France). This won Santos-Dumont the Deutsch-Archdeacon Prize for the first officially-observed flight of more than 25 meters. Aviation historians generally recognise it as the first powered flight in Europe. Then on 12 November a flight of 22.2 seconds carried the 14-bis some 220 m (720 ft), earning the Aéro-Club prize of 1,500 francs for the first flight of more than 100 m.[38] This flight was also observed by the newly formed Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) and became the first record in their log book.

The lateral control system comprised ailerons mounted between the wings and attached to a harness worn by the pilot, who was intended to correct any rolling movement by leaning in the opposite direction.[38] Both flights ended when the craft began to roll and Santos-Dumont landed because he was unable to correct it. This has led some critics to question the lateral control capability of the 14-bis, however it has not prevented the flight from being recognised.[6] At that time the Wrights' claim had not yet been accepted in Europe and was questioned in America by the authoritative Scientific American. Thus, Santos-Dumont was credited by many with the first powered flight.[39]

Other claims

In 1894 Hiram Maxim tested a flying machine running on a track and held down by safety rails because it lacked adequate flight control. The machine lifted off the track and met the safety rails and this is sometimes claimed as a flight. Maxim himself never made such a claim.[1]

John Hall, of Springfield, Massachusetts was credited, alongside Whitehead, with flights prior to the Wrights by Crane in his 1947 Air Affairs magazine article.

Preston A. Watson was subject of a claim made in 1953 by his brother J.Y. Watson, that he had flown before the Wrights in 1903. J.Y. Watson later admitted that this was in an unpowered glider.[1]

Pearse

Richard Pearse of New Zealand is credited by some in his country with making the first powered airplane flight on 31 March 1903.[40] He did not claim the feat himself and gave ambiguous information about the chronology of his work.[40][41] Biographer Geoffrey Rodliffe wrote, "no responsible researcher has ever claimed that he achieved fully controlled flight before the Wright brothers, or indeed at any time".[42]

Jatho

Karl Jatho of Germany is generally credited with making powered airborne hops in Hanover between August and November 1903.[43] He claimed a hop of 18 m (59 ft) about 1 m (3 ft) high on August 18, 1903, and several more hops or short flights by November 1903 for distances up to 60 m (197 ft) at 3 m (10 ft) height.[44] His aircraft made takeoffs from level ground. In Germany some enthusiasts credit him with making the first airplane flight.[44] Sources differ whether his aircraft was controlled.[43][45]

Vuia

Traian Vuia is credited with a powered hop of 11 m (36 ft) on March 18, 1906, and he claimed additional powered takeoffs in August.[46][47] His design—a monoplane with a tractor propeller—is recognized as first to show that a heavier-than-air machine could take off on wheels.[48] Romanian sources give him credit as first to take off and fly using his machine's "own self provided energy" and no "external support"—references to not using a rail or catapult, as the Wright brothers had done.[49][50] Santos-Dumont was part of the audience at the March 1906 event.[51]

Ellehammer

Jacob Ellehammer made a tethered powered hop of about 138 ft (42 m) on 12 September 1906. This has been claimed as a flight. Ellehammer's attempt was not officially observed, whereas Santos-Dumont's, only a few weeks later, was observed and has been given primacy.[1]

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gibbs-Smith (1959)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Wragg (1974)

- ↑ Angelucci & Marticardi (1977), Pages 16, 21.

- ↑ "Local inventor beat Wright brothers, Texas townsfolk say". CNN.com. December 17, 2002. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Walker (1974)

- 1 2 Who Was First?, wright-brothers.org (retrieved 6 October 2014): "Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont flew his 14-Bis near Paris, France in the fall of 1906. In October, his best flight covered 196 feet (60 meters); in November, he stretched that to 721 feet (220 meters). Both flights ended when his aircraft entered a roll that Santos-Dumont could not stop and he decided to land, so there is some controversy whether or not these were completely controlled flights. Nonetheless, they are counted as the first "official" flights in Europe."

- ↑ "Chapter 19: Why The Wright Plane Was Exiled". The Wright Brothers. Dayton History Books Online.

- ↑ Crouch, T.; The Bishop's Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Norton 2003.

- 1 2 3 Honious, Ann (2003). ""What Dreams We Have, Appendix C – Tests of the Langley Aerodrome."". National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Weissenborn, G.K.; "Did Whitehead fly?", Air Enthusiast 35, Pilot Press (1988), Pages 19-21 and 74-75.

- 1 2 3 4 Crouch, T.; The Wright-Smithsonian Contract Archived 2016-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, Smithsonian Institution, 2013.

- ↑ "Wright or wrong?". Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt. December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ↑ Hussey, Kristin (April 17, 2015). "First in Flight? Connecticut Stakes a Claim". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ↑ Claudio Ferriera, Luiz (October 23, 2021). "Primeiro voo há 115 anos: Santos Dumont aliou invenções à ciência". Agência Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ↑ "CNN.com - Was the airplane's inventor Brazilian? - Dec. 10, 2003". www.cnn.com. December 10, 2003. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ↑ Scientific American, September 19, 1903, p. 204

- ↑ Sci. American, January 27, 1906

- ↑ "Santos Dumont's Latest Flight", Scientific American, November 24, 1906, p. 378

- ↑ "The Second Annual Exhibition of the Aero Club of America", Scientific American, December 15, 1906, p. 448-449

- ↑ Scientific American, January 25, 1908

- ↑ Malan, Douglas (September 13, 2005), "The Man Who Would Be King: Gustave Whitehead and the battle with the Smithsonian", Connecticut Life, Flying Machines, retrieved May 28, 2011

- ↑ Stella Randolph (1966). Before the Wrights Flew: The Story of Gustave Whitehead. Putnam.

- ↑ Roy Bongartz Jr. (December 1981), "Was Whitehead first?", Popular Mechanics, Hearst Magazines, p. 73, ISSN 0032-4558

- ↑ Jackson, Paul (2013). Jackson, Paul (ed.). "Executive Overview: Justice delayed is justice denied". Jane's All the World's Aircraft 2013. Washington, DC: Macdonald and Jane's: 8–10.

- ↑ "Jane's backs off Gustave Whitehead claim," Archived October 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine 17 April 2015, NAHA News, National Aviation Heritage Alliance

- ↑ Gray, Caroll F., Jane's Points Finger at Editor Huffington Post. Retrieved 14 February 2016

- ↑ Carroll F. Gray (Ed.); "Update # 5: The Photographs - Whitehead Aloft They Are Not" Flying Machines (flyingmachines.org)

- ↑ Schlenoff, Daniel C., Scientific American, June 13, 2013, "Connecticut Proclaims Gustave Whitehead Flew before the Wright Brothers" Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ↑ Gustave Whitehead, flyingmachines.org

- ↑ Howard, F.; Wilbur and Orville: A Biography of the Wright Brothers, Dover 1987.

- ↑ "About this Collection - Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers at the Library of Congress". Library of Congress.

- ↑ "Wright Brothers Negatives - About this Collection". Library of Congress. January 1, 1897.

- ↑ "Wright Brothers Collection (MS-1) - Wright State University Research - CORE Scholar".

- ↑ Dayton Metro Library

- ↑ Gardner, Lester D. (1954). "Book Reviews The Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright". Isis. 45 (3): 316–318. doi:10.1086/348353.

- ↑ "The Wright Catapult". www.wright-brothers.org. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Back to the Beginning", Flight: 505, October 28, 1948

- 1 2 Angelucci & Marticardi (1977)

- ↑ "Primeiro avião do mundo", Rank Brasil: 0, July 20, 2012

- 1 2 "Richard Pearse First Flyer" Archived 2014-10-17 at the Wayback Machine NZEdge.com. Retrieved Oct. 13, 2014

- ↑ "Fact Sheet Richard Pearse" Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT). Retrieved Oct. 13, 2014

- ↑ "Research" Archived 2010-03-06 at the Wayback Machine Avstop.com. Retrieved Oct. 13, 2014

- 1 2 "Karl Jatho". FlyingMachines.org. Carroll Gray. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- 1 2 "First powered flight in the history of aviation". The Karl-Jatho-Project. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Pigs Might Fly: The Gliders & Hoppers". Early Aviation Pioneers. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ↑ Mola, Roger A (August 2009), "The Birthplaces of Aviation. It didn't all happen at Kitty Hawk", Air & Space Magazine

- ↑ "L'Aéroplane à Moteur de M. Vuia". L'Aérophile (in French). September 1906. pp. 195–6.

- ↑ Chanute, Octave (October 1907). "Pending European Experiments in Flying". The American Aeronaut and Aerostatist. 1 (1): 13.

- ↑ "TRAIAN VUIA - in a Century of Aviation -". Romanian Academy Library. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ↑ "About Traian Vuia and his plane". Romanian Coins. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Traian Vuia". earlyaviators.com. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

Bibliography

- Angelucci, E. and Marticardi, P.; World Aircraft: Origins-World War 1, Sampson Low 1977.

- Gibbs-Smith, C.; "Hops and Flights: A Roll Call of Early Powered Take-offs", Flight, Volume 75, Issue 2619, 3 April 1959, Pages 468,469,470.

- Walker, P.; Early Aviation at Farnborough Volume II: The First Aeroplanes, Macdonald 1974.

- Wragg, D.; Flight Before Flying, Osprey 1974.

External links

- O'Dwyer, W.; "The “Who Flew First” Debate," Flight Journal, Oct 1998, pp 22–23, 50–55.

- FlightJournal blog: Who was first the Wrights or Whitehead?. Includes links to other related resources.

- Time The Unlikely Fight Over First in Flight.

- National Geographic Wright Brothers Flight Legacy Hits New Turbulence: Aviation periodical proclaims Gustave Whitehead flew the first airplane.