| Heptanese School |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Regions |

| Eras |

The Heptanese School of painting (Greek: Επτανησιακή Σχολή, lit. 'The School of the Seven Islands', also known as the Ionian Islands School) succeeded the Cretan School as the leading school of Greek post-Byzantine painting after Crete fell to the Ottomans in 1669. Like the Cretan school, it combined Byzantine traditions with an increasing Western European artistic influence and also saw the first significant depiction of secular subjects. The school was based in the Ionian Islands, which were not part of Ottoman Greece, from the middle of the 17th century until the middle of the 19th century. The center of Greek art migrated urgently to the Ionian islands but countless Greek artists were influenced by the school including the ones living throughout the Greek communities in the Ottoman Empire and elsewhere in the world.

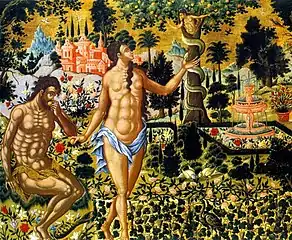

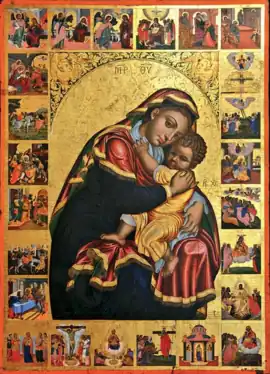

The early Heptanese school was influenced by Flemish, French, Italian and German engravings. Artists representative of that era were Theodore Poulakis, Elias Moskos and Emmanuel Tzanes. Notable works include The Fall of Man and Jacob’s Ladder and Noah's Ark. The early 1700s were influenced by Greek painters Nikolaos Kallergis and Panagiotis Doxaras. Greek art was no longer limited to the traditional maniera greca dominant in the Cretan School but the style evolved into the Stile di pittura Ionico or stile Ionico in English Ionian style. The movement featured a mixture of brilliant artists. They took risks in creating art that escaped tradition. Some examples of paintings include: Virgin Glykofilousa The Deposition from the Cross and Assumption of Mary. In the 1800s the Heptanese school featured prominent portrait painters Nikolaos Kantounis, Nikolaos Koutouzis and Gerasimos Pitsamanos. Other artists of the school included Spyridon Ventouras, Efstathios Karousos, Stephanos Tzangarolas and Spyridon Sperantzas.[1][2][3]

History

_cropped.jpg.webp)

The Ionian Islands or Heptanese from the 17th to the 19th century were under successive Venetian, French and English occupation. The relative freedom that the Heptanesian people enjoyed compared with the Ottoman-ruled mainland Greece, and the vicinity and the cultural relationships with neighboring Italy, resulted in the creation of the first modern art movement in Greece. Another reason for the regional blossoming of arts is the migration of artists from the rest of the Greek world, and especially Crete, to the Heptanese to escape Ottoman rule. From the Fall of Constantinople in the mid-15th century until its conquest by the Ottomans in the 17th century, Crete, also ruled by Venice, had been the main cultural center of Greece, giving rise to the Cretan School. The main representatives of the fusion of Heptanese and Cretan Schools are Michael Damaskinos, Spyridon Ventouras, Dimitrios and George Moschos, Manolis Tzanes, Konstantinos Tzanes and Stephanos Tzangarolas.[3]

Artistic styles

Art in the Heptanese shifted towards Western styles by the end of the 17th century with the gradual abandonment of strict Byzantine conventions and techniques. Artists were now increasingly influenced by the Italian Baroque and Flemish painters rather than from their Byzantine heritage. Paintings began to have a three-dimensional perspective and the compositions became more flexible using Western realism, departing from the traditional representations that embodied Byzantine spirituality. Such changes were also reflected on the technique of oil painting on canvas which replaced the Byzantine technique of egg tempera on panel. Subjects included secular portraits of the bourgeoisie, which became more common than religious scenes.[4] Bourgeois portraiture had an emblematic character which emphasised the class, profession and position of the individual in society. Frequently, however, these works also constitute penetrating psychological studies. The mature phase of the School of the Ionian Islands echoes the social developments as well as the changes that had occurred in the visual arts. Portraits began to lose their emblematic character. The early rigid poses were then succeeded by more relaxed attitudes. Other subjects from the School of the Ionian Islands included genre scenes, landscapes, and still lifes.[4]

Heptanese School

.jpg.webp)

The Heptanese was characterized by the influx of countless artists to the Ionian Islands. The early school shared characteristics with the late Cretan School. The Greek community continued to prefer the Greek style over traditional Renaissance Baroque-influenced oil paintings. Theodore Poulakis, Elias Moskos, and Emmanuel Tzanes were the early proponents of the Heptanese school.[5] Heptanese art was characterized by art modeled after Italian, Dutch, and Flemish engravings. Some of the engravers were Cornelis Cort, Adriaen Collaert, Hieronymus Wierix, Jan Wierix, Hendrick Goltzius, and Francesco Villamena.[6] For example, Poulaki's Noah's Ark was influenced by an engraving created by Jan Sadeler. Zakynthian painter Demetrios Stavrakis also adopted Sadeler's work in The Prophet Jonah. Two other notable engravers from the Sadeler family were Raphael Sadeler I, and Aegidius Sadeler II. By the 1700s, Greek art continued to evolve but Tintoretto and Damaskinos influenced Greek art far less. The art of Greece included influences from all over the world Belgium, France, Germany, and Spain. Some Greek art also exhibited Ottoman characteristics. Several of Panagiotis Doxaras's Greek-style paintings heavily influenced the new image of the Heptanese school.[7]

His oil paintings modeled after Leonardo da Vinci were not the major driving force of the new Greek art movement. Some of the proponents of the school included Efstathios Karousos, Nikolaos Kallergis, Spyridon Ventouras, Stylianos Stavrakis and Konstantinos Kontarinis.

The early Heptanese school was heavily characterized by paintings modeled after engravings such as The Fall of Man and Jacob’s Ladder. Both painters belong to the late Cretan School and early Heptanese School. By the 1700s, artists were making bold changes to their artwork. This is visible in the Virgin Glykofilousa with the Akathist Hymn .[8] Corfu artist Stephanos Tzangarolas introduced a more refined technique. He influenced the Virgin Glykofilousa painted by Kephalonian artist Andreas Karantinos. Around the same period Panagiotis Doxaras was experimenting with his Greek style.[7] One notable painting of Christ is part of the iconostasis at Saint Demetrios Church. Zakynthos painter Nikolaos Kallergis also began to influence the evolution of the Greek style. His work Angel Holding Symbols of the Passion defines the new movement.[9]

The Greeks grew out of the term maniera greca. The terminology solely lies with the Cretan School. Stile di pittura Ionico or stile Ionico. The Ionian style defines the art of the Heptanese school which would be traditionally viewed as the maniera greca. By the middle of the 1700s Zakynthos painter Stylianos Stavrakis created his own version of the Vision of Constantine (Stavarkis). It exhibited characteristics of the Late Cretan School but is representative of the stile Ionico.

Artists from Lefkada began to paint a shared theme relating to the life of John Chrysostom. Spyridon Ventouras created a notable painting called A Scene from the Life of John Chrysostom in 1797.[10][11]

Three artists carried the art of the Heptanese school outside of the Greek world. Spyridon Sperantzas traveled to Trieste where he had a successful active workshop. Efstathios Karousos finished major works in Naples. and Spiridione Roma traveled to Sicily than England. The art of the Heptanese School also influenced other Greek painters living outside of the Greek artistic epicenter. Athenian fresco painter Georgios Markou traveled to Venice and the Ionian islands. Countless works were sold throughout the Greek community and Heptanese painting was the prevalent style in Greek communities. Many works were sent to the two major Greek monasteries Mount Athos and Mount Sinai. By the 1800s the school evolved and could sustain portrait painters. Some of the painters included Gerasimos Pitsamanos, Nikolaos Kantounis, and Nikolaos Koutouzis. Nikolaos Kantounis and Nikolaos Koutouzis each feature artistic catalogs with over 100 paintings.

Oil painters

Some examples of the new western influenced art can be seen on the frescoed ceilings of churches which were known as ourania or sofita. A pioneer in the change was Panagiotis Doxaras (1662–1729), a Maniot who was taught Byzantine iconography from the Cretan Leos Moskos. Later Doxaras traveled to Venice to study painting. He abandoned Byzantine iconography to dedicate himself to western art. He used the works of Paolo Veronese as his guide. He later frescoed the ceiling of the church of Saint Spyridon in Corfu.[12]

In 1726, he wrote the famous although controversial and much-debated theoretical text On painting (Περί ζωγραφίας) in which he addressed the need for Greek art to depart from the Byzantine art towards western European art. His article even today is the subject of much discussion in Greece.[13]

Nikolaos Doxaras (1700/1706–1775), son of Panagiotis Doxaras continued the artistic legacy of his father. Between 1753 and 1754, he frescoed the ceiling of Saint Faneromeni Church, in Zakynthos. Regrettably, it was destroyed by an earthquake in 1953. Only a part of it was saved. It is exhibited today at the local museum. Other contemporary artists of Doxaras were Ieronymos Stratis Plakotos (c.1662-1728), also from Zakynthos, and the Corfiot Stefanos Pazigetis.

The Zakynthos priests and painters Nikolaos Koutouzis (1741–1813) and his pupil Nikolaos Kantounis (1767–1834) continued to paint according to western European standards and were particularly known for their realistic portraiture that emphasizes the emotional background of the subject. Dionysios Kallivokas (1806–1877) and Dionysios Tsokos (1820–1862) are generally considered to be the last painters of the Heptanese School.[3]

Later Heptanese artists

The sculptor and painter Pavlos Prosalentis is the first neoclassical sculptor of modern Greece. Ioannis Kalosgouros, a sculptor, architect and painter produced the marble bust of Countess Helen Mocenigo, a portrait of Nikolaos Mantzaros and a portrait of Ioannis Romanos. Ioannis Chronis was another exponent of the prevailing neoclassical architectural trend. Some of his most important works are the Capodistria Mansion, the Ionian Bank, the former Ionian Parliament, the churches of St. Sophia and All Saints and the little church of Mandrakina. Dionysios Vegias was born in Cephalonia in 1819, considered to be one of the first to practice the art of engraving in Greece. Charalambos Pachis founded in 1870 a private school of painting in Corfu and is considered as the most important landscape painter of the Heptanese School along with Angelos Giallinas that specialised in watercolours. Another well-known painter is Georgios Samartzis, who was almost restricted to portraiture. Spyridon Skarvellis is best known for his watercolours and Markos Zavitsianos excelled in portrait painting and is considered an outstanding exponent of pictorial art in Greece.[14]

End of the Heptanese School period

Later Heptanese painters such as Nikolaos Xydias Typaldos (1826/1828–1909), Spyridon Prosalentis (1830–1895), Charalambos Pachis (1844–1891), and many others seem to distance themselves from the Heptanese school principles and are influenced by more modern Western European artistic movements. The liberation of Greece has transferred the Greek cultural centre from the Heptanese to Athens. Particularly important for that was the foundation in 1837 of the Athens Polytechnic that preceded the Athens School of Fine Arts. In the new school many artists were invited to teach such as the Italian Raffaello Ceccoli (fl.1839-1852), the French Pierre Bonirote, the German Ludwig Thiersch and the Greeks Stefanos Lantsas and his father, Vikentios. Among the first students of the school was Theodoros Vryzakis.

Research

The Heptanese School features countless works of art and artists. Manolis Hatzidakis conducted massive research in the field. He is considered the 20th century Giorgio Vasari and Bernardo de' Dominici. He helped shape the Institute of Neohellenic Research. Three important Encyclopedias were published within the last thirty years cataloging painters and artists. The books feature records of countless artists from the Fall of the Byzantine Empire until the onset of modern Greece. It is the first time in history Greek painters were listed on this magnitude and scale. The work is similar to Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects and Bernardo de' Dominici's Vite dei Pittori, Scultori, ed Architetti Napolitani.

The encyclopedias feature thousands of frescos, paintings, and other artistic works. The books illustrate hundreds of painters. Regrettably, the three volumes are currently available in Greek and are entitled Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450-1830) or Greek painters after the fall (1450-1830). Eugenia Drakopoulou and Manolis Hatzidakis were the predominant contributors. The three volumes were published in 1987, 1997, and 2010. The books feature many artists from the Heptanese School during the Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassicism, and Romanticism periods in Greek art. The books feature artists and artwork up until the Modern Greek art period. Drakopoulou continues research for the institute until today.[15]

Greece and the European Union have digitally archived hi-resolution paintings, frescoes, and other works of art after the fall of Constantinople (1450-1830). The government also features biographical details and an index of artistic works. The Institute of Neohellenic Research cataloged portable icons, church frescoes, and or any other artistic works. It is the first time in history a systematic record was accumulated in Greece representing the period.[15]

Gallery

"Archangel Michael" by Panagiotis Doxaras

"Archangel Michael" by Panagiotis Doxaras Virgin with Child by Charalambos Pachis

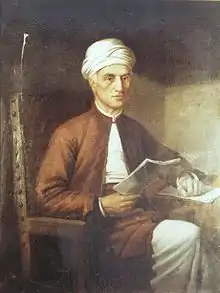

Virgin with Child by Charalambos Pachis Portrait of Dimitrios Galanos by Spyridon Prosalentis

Portrait of Dimitrios Galanos by Spyridon Prosalentis Murder of Ioannis Kapodistrias by Charalambos Pachis

Murder of Ioannis Kapodistrias by Charalambos Pachis Portrait of a man by Nikolaos Xydias Typaldos

Portrait of a man by Nikolaos Xydias Typaldos Chemist Nikopoulos by Nikolaos Kantounis

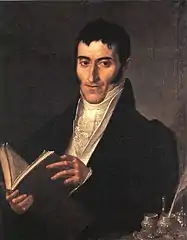

Chemist Nikopoulos by Nikolaos Kantounis Portrait of an erudite by Nikolaos Koutouzis

Portrait of an erudite by Nikolaos Koutouzis Carnival in Kerkyra by Charalambos Pachis

Carnival in Kerkyra by Charalambos Pachis Dance in Corfu by Dionysios Vegias

Dance in Corfu by Dionysios Vegias_by_Tsokos.jpg.webp) Dame by Dionysios Tsokos

Dame by Dionysios Tsokos

See also

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Greek art |

|---|

|

References

- ↑ Hatzidakis 1987, pp. 96–132.

- ↑ Thomopoulos 2021, pp. 250, 258.

- 1 2 3 archive.gr – Διαδρομές στην Νεοελληνική Τέχνη Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 "New Page 1". Archived from the original on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ↑ Hatzidakis & Drakopoulou 1997, pp. 198–203, 304–317, 408–423.

- ↑ Alevizou 2018, p. 10.

- 1 2 Drakopoulou 2010, pp. 272–274.

- ↑ Katselakì 1999, pp. 375–384.

- ↑ Hatzidakis & Drakopoulou 1997, pp. 53–56.

- ↑ Hatzidakis & Drakopoulou 1997, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Hatzidakis 1987, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Λάμπρου, Σπ.: Συμπληρωματικαί ειδήσεις περί του ζωγράφου Παναγιώτου Δοξαρά Ν. *Ελληνομνήμων ή Σύμμικτα Ελληνικά, τ. 1, 1843

- ↑ Δοξαράς, Παναγιώτης: Περί ζωγραφίας, εκδ. Σπ. Π. Λάμπρου, εν Αθήναις, 1871; Αθήνα (Εκάτη 1996)

- ↑ "Culture: Fine Arts". Archived from the original on 2008-12-29. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- 1 2 Hatzidakis 1987, pp. 73–132.

Bibliography

- Thomopoulos, Elaine (2021). Modern Greece. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440854927.

- Hatzidakis, Manolis (1987). Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450-1830). Τόμος 1: Αβέρκιος - Ιωσήφ [Greek Painters after the Fall of Constantinople (1450-1830). Volume 1: Averkios - Iosif]. Athens: Center for Modern Greek Studies, National Research Foundation. hdl:10442/14844. ISBN 960-7916-01-8.

- Hatzidakis, Manolis; Drakopoulou, Evgenia (1997). Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450-1830). Τόμος 2: Καβαλλάρος - Ψαθόπουλος [Greek Painters after the Fall of Constantinople (1450-1830). Volume 2: Kavallaros - Psathopoulos]. Athens: Center for Modern Greek Studies, National Research Foundation. hdl:10442/14088. ISBN 960-7916-00-X.

- Drakopoulou, Evgenia (2010). Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450–1830). Τόμος 3: Αβέρκιος - Ιωσήφ [Greek Painters after the Fall of Constantinople (1450–1830). Volume 3: Averkios - Joseph]. Athens, Greece: Center for Modern Greek Studies, National Research Foundation. ISBN 978-960-7916-94-5.

- Vassilaki, Maria (2012). Οι Εικόνες του Αρχοντικού Τοσίτσα Η Συλλογή του Ευαγγέλου Αβέρωφ [The Icons of the Tositsa Mansion The Collection of Evangelou Averoff]. Athens, GR: The Foundation of the Baron Michael Tositsa. p. 150. ISBN 978-960-93-3497-6.

- Komini-Dialeti, Dora (1997). Λεξικό Ελλήνων Καλλιτεχνών Ζωγράφοι, Γλύπτες, Χαράκτες, 16ος-20ός Αιώνας [Dictionary of Greek artists Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, 16th-20th century]. Athens, Greece: Melissa. ISBN 9789602040355.

- Vassilaki, Maria (2015). Working Drawings of Icon Painters after the Fall of Constantinople The Andreas Xyngopoulos Portfolio at the Benaki Museum. Athens, Greece: Leventis Gallery & Benaki Museum.

- Hatzidakis, Nano M. (1998). Icons, the Velimezis Collection: Catalogue Raisonné. Athens, Greece: Museum Benaki.

- Acheimastou Potamianou, Myrtalē (1998). Icons of the Byzantine Museum of Athens. Athens, Greece: Ministry of Culture. ISBN 9789602149119.

- Alevizou, Denise C (2018). Il Danese Paladino in a Late Seventeenth-century Icon by Elias Moskos. Crete, Greece: Cretica Chronica. ISSN 0454-5206.

- Katselakì, Andromache (1999). Εικόνα Παναγίας Γλυκοφιλούσας από την Κεφαλονιά στο Βυζαντινό Μουσείο [An Icon of the Panagia Glykophilousa from Kephalonia in the Byzantine Museum]. Athens: Journal of the Christian Archaeological Society ChAE 20 Period Delta.

- Kakavas, George (2002). Post-Byzantium The Greek Renaissance : 15th-18th Century Treasures from the Byzantine & Christian Museum, Athens. Athens, Greece: Hellenic Ministry of Culture Onassis Cultural Center.

- Speake, Graham (2021). Encyclopedia of Greece and the Hellenic Tradition. London And New York: Rutledge Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 9781135942069.

- Tselenti-Papadopoulou, Niki G. (2002). Οι Εικονες της Ελληνικης Αδελφοτητας της Βενετιας απο το 16ο εως το Πρωτο Μισο του 20ου Αιωνα: Αρχειακη Τεκμηριωση [The Icons of the Greek Brotherhood of Venice from 1600 to First Half of the 20th Century] (PDF). Athens: Ministry of Culture Publication of the Archaeological Bulletin No. 81. ISBN 960-214-221-9.

- Eugenia Drakopoulou (June 11, 2022). "Digital Thesaurus of Primary Sources for Greek history and Culture". Institute for Neohellenic Research. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

External links