| Ischium of pelvis | |

|---|---|

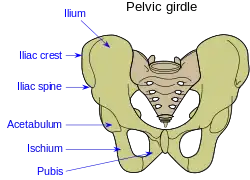

Pelvic girdle | |

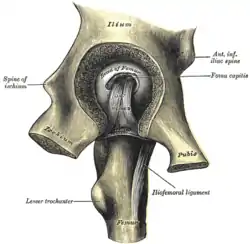

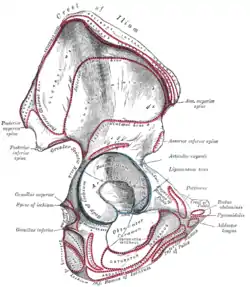

Left hip-joint, opened by removing the floor of the acetabulum from within the pelvis. (Ischium labeled at bottom left.) | |

| Details | |

| Origins | Superior gemellus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os ischii |

| MeSH | D007512 |

| TA98 | A02.5.01.201 |

| TA2 | 1339 |

| FMA | 16592 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The ischium (/ˈɪski.əm/;[1] pl.: ischia) forms the lower and back region of the hip bone (os coxae).

Situated below the ilium and behind the pubis, it is one of three regions whose fusion creates the coxal bone. The superior portion of this region forms approximately one-third of the acetabulum.

Structure

The ischium is made up of three parts–the body, the superior ramus and the inferior ramus. The body contains a prominent spine, which serves as the origin for the superior gemellus muscle. The indentation inferior to the spine is the lesser sciatic notch. Continuing down the posterior side, the ischial tuberosity is a thick, rough-surfaced prominence below the lesser sciatic notch. This is the portion that supports weight while sitting (especially noticeable on a hard surface) and can be felt simply by sitting on the fingers. It serves as the origin for the inferior gemellus muscle and the hamstrings. The superior ramus is a partial origin for the internal obturator and the external obturator muscles. The inferior ramus serves partially as origin for part of the adductor magnus muscle and the gracilis muscle. The inferior ischial ramus joins the inferior ramus of the pubis anteriorly and is the strongest of the hip (coxal) bones.

Body

The body enters into and constitutes a little more than two-fifths of the acetabulum. Its external surface forms part of the lunate surface of the acetabulum and a portion of the acetabular fossa. Its internal surface is part of the wall of the lesser pelvis; it gives origin to some fibers of the internal obturator. No muscles insert on the body.

Its anterior border projects as the posterior obturator tubercle. From its posterior border there extends backward a thin and pointed triangular eminence, more or less elongated in different subjects, the ischial spine, origin of the gemellus superior muscle.

Above the spine is a large notch, the greater sciatic notch; Below the spine is a smaller notch, the lesser sciatic notch.

Superior ramus

The superior ramus of the ischium (descending ramus) projects downward and backward from the body and presents for examination three surfaces: external, internal, and posterior.

The external surface is quadrilateral in shape. It is bounded above by a groove that lodges the tendon of the external obturator; below, it is continuous with the inferior ramus; in front it is limited by the posterior margin of the obturator foramen; behind, a prominent margin separates it from the posterior surface. In front of this margin the surface gives origin to the quadratus femoris, and anterior to this to some of the fibers of origin of the external obturator; the lower part of the surface gives origin to part of the adductor magnus.

The internal surface forms part of the bony wall of the lesser pelvis. In front it is limited by the posterior margin of the obturator foramen. Below, it is bounded by a sharp ridge that provides attachment to a falciform prolongation of the sacrotuberous ligament, and, more anteriorly, gives origin to the transverse perineal and ischiocavernosus muscles.

Posteriorly the ramus forms a large swelling, the tuberosity of the ischium, where the hamstrings originate.

Inferior ramus

The inferior ramus of the ischium (ascending ramus) is the thin, flattened part of the ischium, which ascends from the superior ramus, and joins the inferior ramus of the pubis—the junction being indicated in the adult by a raised line.

The outer surface is uneven for the origin of the obturator externus and some of the fibers of the adductor magnus; its inner surface forms part of the anterior wall of the pelvis.

Its medial border is thick, rough, slightly everted, forms part of the outlet of the pelvis, and presents two ridges and an intervening space.

The ridges are continuous with similar ones on the inferior ramus of the pubis: to the outer is attached the deep layer of the superficial perineal fascia (fascia of Colles), and to the inner the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm.

Tracing these two ridges downward, they join with each other just behind the point of origin of the transverse perineal muscles. Here the two layers of fascia are continuous behind the posterior border of the muscle.

To the intervening space, just in front of the point of junction of the ridges, the transverse perineal attaches, and in front of this is a portion of the ischiocavernosus, and the crus penis in the male, or the crus clitoridis in the female.

Its lateral border is thin and sharp, and forms part of the medial margin of the obturator foramen.

Clinical significance

Clinically, an avulsion fracture of the ischial tuberosity may occur.[2]

Avulsion fractures of the hip bone (avulsion or tearing away of the ischial tuberosity) may occur in adolescents and young adults during sports that require sudden acceleration or deceleration forces, such as sprinting or kicking in football, soccer, jumping hurdles, basketball, and martial arts. These fractures occur at tubercles (bony projections that lack secondary ossification centers). Avulsion fractures occur where muscles are attached: anterior superior and inferior iliac spines, ischial tuberosities, and ischiopubic rami. A small part of bone with a piece of a tendon or ligament attached is avulsed (torn away).[3]

Ischial bursitis (also known as weaver's bottom) is inflammation of the synovial bursa located between the gluteus maximus muscle and the ischial tuberosity,[4] and is usually caused by prolonged sitting on a hard surface.

History

Adoption of ischium into English-language medical literature dates back to c. 1640; the Latin term derives from Greek ἰσχίον iskhion meaning "hip joint". The division of the acetabulum into ischium (ἰσχίον) and ilium (λαγών, os lagonicum) is due to Galen, De ossibus. Galen, however, omits mention of the pubis as a separate bone.[5]

Other animals

Dinosaurs

The clade Dinosauria is divided into the Saurischia and Ornithischia based on hip structure, including importantly that of the ischium.[6] In the majority of dinosaurs, the ischium extends down from the ilium and towards the tail of the animal. The acetabulum, which can be thought of as a "hip-socket", is a cup-shaped opening on each side of the pelvic girdle formed where the ischium, ilium, and pubis all meet, and into which the head of the femur inserts. The orientation and position of the acetabulum is one of the main morphological traits that caused dinosaurs to walk in an upright posture with their legs directly underneath their bodies.[7]

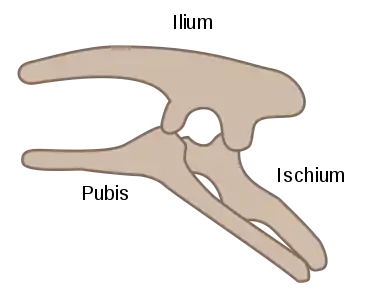

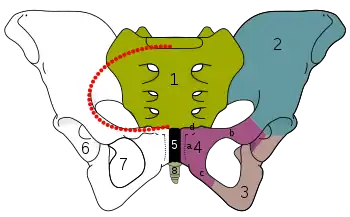

Ornithischian pelvic structure (left side)

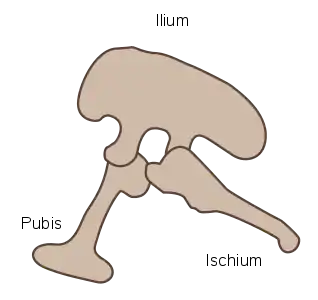

Ornithischian pelvic structure (left side) Saurischian pelvic structure (left side).

Saurischian pelvic structure (left side).

Additional images

Right hip bone. External surface.

Right hip bone. External surface. Right hip bone. Internal surface.

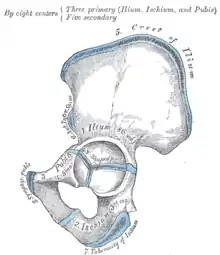

Right hip bone. Internal surface. Plan of ossification of the hip bone.

Plan of ossification of the hip bone.

The Obturator externus.

The Obturator externus. Pelvis

Pelvis

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 234 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 234 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ "ischium". The Free Dictionary.

- ↑ Wootton, JR; Cross, MJ; Holt, KW (July 1990). "Avulsion of the ischial apophysis. The case for open reduction and internal fixation". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 72 (4): 625–7. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.72B4.2380217. PMID 2380217.

- ↑ Dalley, Keith L. Moore, Anne M.R. Agur, Arthur F. (2010). Clinically oriented anatomy (6th ed., [International ed.]. ed.). Philadelphia [etc.]: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1605476520.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Fauci, Anthony (2010). Harrison's Rheumatology, Second Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing; Digital Edition. p. 271. ISBN 9780071741460.

- ↑ De ossibus chapter 20, ed. Kühn, vol. 2, p. 772, cited after Charles Singer, C. Rabin, A Prelude to Modern Science: Being a Discussion of the History, Sources and Circumstances of the 'Tabulae Anatomicae Sex' of Vesalius, Cambridge University Press, 1946 (reprinted 2012), p. 35.

- ↑ Seeley, H.G. (1888). "On the classification of the fossil animals commonly named Dinosauria." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 43: 165-171.

- ↑ Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. pg. 299-300. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5.

- Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy and Physiology The Unity of Form and Function. 5th ed. McGraw-Hill Science Engineering, 2009. Print.

External links

- Anatomy photo:44:st-0722 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Peniel: Hip Bone"

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-15—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna