Susa is one of the most important archaeological sites in Iran, on the border between the Mesopotamian world and the Persian world. Inhabited since very ancient times (4500 BC), it remained occupied until the middle of the 15th century. Excavations carried out by French teams, allowed the discovery of many objects, including a large production of ceramics dating from the Islamic period, currently kept for a large part (more than 2000 objects listed) at the Louvre (their number of inventory consists of the letters MAO S. and a number).[1]

Problems related to the study of the Susa site

Several problems arise when studying the ceramics of Susa.

Some are linked to the conditions of the excavations: Islamic archeology is now completely devastated. In the 19th century and early 20th century, excavators practiced biblical archeology, seeking information on ancient cities, which led them to destroy most of the Islamic levels, saving some pieces but wiping out stratigraphies and archaeological contexts. . Susa, whose excavations began in 1897, was no exception. A French mission in the 1970s nevertheless enabled Monique Kervran to establish a very complete stratigraphic table for each type of ceramic.[2]

Other problems are linked to the objects themselves: indeed, the development of ceramic production is not very fast. The relatively easy conquest of the Muslim armies in the first half of the 7th century allowed production to continue without too much trouble, and the models of production seem to pass from one generation to the next without undergoing major changes. It is therefore difficult, for certain pieces, to determine whether or not they are Islamic, or to suggest a reduced dating.without too much trouble, and the models of production seem to pass from one generation to the next without undergoing major changes. It is therefore difficult, for certain pieces, to determine whether or not they are Islamic, or to suggest a reduced dating.[3]

Status of ceramics at the Susa site

The production of terracotta in the city seems quite probable, given the abundance of material and the discovery of pottery material such as baking sticks and molds.[4]

Stratigraphy of the site for the Islamic period

In the most recent excavations, where a stratigraphy was established, five periods could be distinguished:

- Level IIIa: dated from the end of the 6th to the middle of the 7th century

- level IIIb: dated from the middle of the 7th to the end of the 8th century

- level IIa: dated from the end of the 8th to the first half of the 9th century, this layer contains the so-called “pre-Samarra” pottery.

- level IIb: dated from the middle of the 9th century to the end of it, this level is contemporary with level II of the site of Al-Hirah and the occupation of that of Samarra.

- level I: dated from the first half of the 10th century at the end of the site.

Materials and techniques

All the Susa ceramics are made of clay paste, a fairly plastic material, which can sometimes lead to extremely sophisticated productions, such as that of egg-shell, the thickness of the walls of which is reduced to a few millimeters. The color of the clay varies according to its impurities and the degreaser (material which facilitates the work, such as pieces of straw, chamotte, grains) which is added to it. Nevertheless, it is most often very clear, a little pinkish or buff.[5]

The different types of ceramic

Ceramics are classified according to their decoration technique and their shape.

Islamic Unglazed ceramics

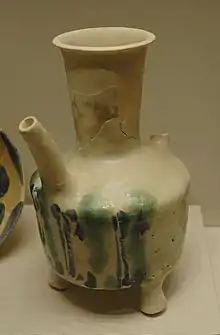

Numerous production, varied from the point of view of forms, decorations and quality, unglazed ceramic was produced throughout the period. There are jugs, pitchers (the first not having a spout, unlike the second), jars, their supports and lids, open shapes (pots, bowls, vases), lamps.[6]

The shapes sometimes make it possible to distinguish the periods. This is the case for the jugs and pitchers, the most important group preserved: the first are placed in the lineage of the Sassanid forms (pear-shaped, slender body, narrow neck marked at the base by a projection, etc.); they disappeared in the 8th century in favor of a type of pear-shaped pitcher, the surface of which was treated in a new way, with veins made by applying a wet cloth or hands before cooking.[7]

A jug, inspired by Sassanid models, appeared at the same time - late 7th-early 8th century. Its decoration is gouged (hollowed out with a gouge) and incised, its high quality paste reflects the refinement of these series, which disappeared at the beginning of the 9th century.[8]

Another jug, whose origins date back to Mediterranean metal, was made during this period, in two parts molded separately and put together with mud. Like other Abbasid pieces, it has an updated profile. In the middle of the 8th century, egg-shell pieces, with an extremely fine paste, began to be produced.Inspired by metallic samples, they are of two types, with a double casing profile or with a globular body decorated with fine incisions. Egg-shells were produced until the middle of the tenth century, but the shapes gradually became heavier.[9]

On top of that, establish a typology of each type of object: pots and jars, which serve to protect the food from insects and dust.Some of the objects, In the Parthian tradition, were made in the shape of cups or decorations (mid-8th - 10th century), some others in a circular and flat shape, with a button in strong relief and an incised or combed decoration, (from the middle of the 8th century).[10]

For the jars, it is from the decoration that is classified as the pieces, the Sassanid form being perpetuated until the 13th century. Thus, the bands molded and applied with the slip, with friezes of lions passing, derived from the Sassanid model, are typical of the beginning of the period (7th - 8th century) and of the region of the site, Khuzistan.The relief decorations, plant or animal, are applied with slip and finely incised, although they were created before the Islamic period, they were s mainly made at the beginning of the Abbasid period. As for the molded and applied decoration, it may have appeared at the end of the 8th century (palmettes, stylized florets, incised ribbons). In the 11th century, we find interwoven ribbons and animal motifs applied to jars of very coarse yellow paste.[11]

Glazed ceramics

Transition pieces and pieces with simple glaze decoration

The glaze works already existed before the Islamic period, especially in the Iranian provinces. They then used an alkaline fluid.[12]

The production of glazed ceramics did not stop abruptly with the arrival of Islam, but on the contrary continued for some time. Thus, we know of jars and amphorae probably produced after the conquest, but which retain the old models.

From a decorative point of view, these pieces are covered with a monochrome glaze, most often yellow or green. The small palm tree pitcher, meanwhile, is quite unique since it is decorated with yellow and green glazes enclosed in black lines that prevent it from melting, which foreshadows the cuerda seca technique. Pieces with molded underglaze decoration, in particular shuttles, a form which reflects the Sassanid example, have also been found. Sometimes, the molding creates a partition between the glazes, which thus do not melt. A final technique used with the glaze is the use of it to create patterns, such as pseudo-epigraphies in particular.[13]

Earthenware

Earthenware is one of the two great innovations developed in the Islamic world. These are clay pieces, covered with a tin glaze (white and opaque), which, after being cooked in fire, are decorated at a higher temperature on the glaze and are strengthened. The colors that resist these high temperatures and remain on the coins of Susa are blue (cobalt oxide), green (copper oxide), brown (manganese oxide) and yellow (antimony oxide), these last two colors are much less frequent than the first ones.The decor in blue on a white background is also very popular; the blue, penetrating into the glaze, slightly blurs the outlines of the design, which then appears a little cloudy.[14]

Some pieces imitate earthenware, by painting a decoration on a white slipware. Others use cassiterite instead of tin in the glaze, which causes alterations, which the Susa soil, quite acidic, favors: the glazes turn gray after prolonged burial.

Several earthenware substances exist. One of them, called "splashware", or "marbled decoration", consists in running glazes of various colors in order to obtain marbling. It is believed that this technique derives from an influence of Chinese sensai pieces (3 colors), of which some examples are found on the site of Susa itself, together with green and white Stoneware. Although the quantity of these samples found is so small, it seems that it is these ceramics that gave the impetus to earthenware.[15]

The shapes of the pieces vary a lot, torn between Chinese, Sassanid and Mediterranean influences. Metal from the near-eastern region is often used as a model, as shown by the keeled shapes, which take up these samples.

Metallic chandeliers

The second great technique developed by Islamic potters, metallic, polychrome or monochrome luster, constitutes an important set of ceramics found in Susa. As with earthenware, the piece is cooked in two stages, the first for the paste and the clouded Ethane, the second for the decoration.

This second cooking is carried out partly in a reducing manner. That is to say without supply of oxygen which makes it possible to convert the paste of silver and copper oxides, placed on the piece, into a shiny decoration. The decorations vary a lot over time, which makes it possible to classify the parts quite easily.

From the 10th century, the chandelier, at Susa as in other sites, seems to change direction, passing from polychromy to monochromy. The exact date of this change, fundamental for the whole history of Islamic ceramics, remains very vague, for lack of a precise chronological marker.We can nevertheless make several remarks concerning the stylistic evolution of the decorations.We are thus witnessing the appearance of a figurative, animal and anthropomorphic decoration, very stylized, geometric and without re-engraving.

References

- ↑ Susa

- ↑ Publié dans les cahiers de la DAFI

- ↑ Europe & the Islamic Mediterranean AD 700–1600

- ↑ The Organization of Ceramic Production during the Susa I Period

- ↑ Persian pottery: A masterpiece of pottery art

- ↑ CERAMICS xiii. The Early Islamic Period, 7th-11th Centuries

- ↑ studies in ancient technology, Volume

- ↑ Islamic archaeology at Susa

- ↑ The Art of the Abbasid Period (750–1258)

- ↑ BISOTUN ii. Archeology

- ↑ CERAMICS xiii. The Early Islamic Period, 7th-11th Centuries

- ↑ Early Islamic Ceramics and Glazes

- ↑ Iranian Ceramics Assemblages Represented in the Milwaukee Public Museum

- ↑ BETWEEN THE COLORATION AND THE FIRING TECHNOLOGY USED TO PRODUCE SUSA GLAZED CERAMICS OF THE END OF THE NEOLITHIC PERIOD

- ↑ CERAMICS xiii. The Early Islamic Period, 7th-11th Centuries