| Horny cone-bush | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Isopogon |

| Species: | I. ceratophyllus |

| Binomial name | |

| Isopogon ceratophyllus | |

| |

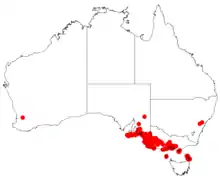

| Occurrence data from Australasian Virtual Herbarium | |

| Synonyms | |

Isopogon ceratophyllus, commonly known as the horny cone-bush or wild Irishman, is a plant of the family Proteaceae that is endemic to the coast in Victoria, South Australia and on the Furneaux Group of islands in Tasmania. It is a small woody shrub that grows to 100 cm high with prickly foliage. It is extremely sensitive to dieback from the pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi

Description

Isopogon ceratophyllus is a prickly shrub, growing to 15–100 cm (6–40 in) tall and to 120 cm (4 ft) across. The oval to round flower heads, known as inflorescences, appear between July and January, and are around 3 cm in diameter.[2]

Taxonomy

Isopogon ceratophyllus was first described by Robert Brown in his 1810 work Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae et Insulae Van Diemen.[1][3] The specific epithet is derived from the Ancient Greek words cerat- "horn" and phyllon "leaf", relating to the leaves' resemblance to antlers.[4] In 1891, German botanist Otto Kuntze published Revisio generum plantarum, his response to what he perceived as a lack of method in existing nomenclatural practice.[5] Because Isopogon was based on Isopogon anemonifolius,[6] and that species had already been placed by Richard Salisbury in the segregate genus Atylus in 1807,[7] Kuntze revived the latter genus on the grounds of priority, and made the new combination Atylus ceratophyllus for this species.[8] However, Kuntze's revisionary program was not accepted by the majority of botanists.[5] Ultimately, the genus Isopogon was nomenclaturally conserved over Atylus by the International Botanical Congress of 1905.[9]

Common names include horny cone bush and, from Kangaroo Island, wild Irishman.[4]

Distribution and habitat

The species ranges from south-western Victoria into the south-eastern corner of South Australia[2] and in the Furneaux Group of Bass Strait islands, principally Flinders, Cape Barren and Clarke Islands. A King Island record has not been reconfirmed and is unlikely.[10] It is the only Isopogon species found in South Australia.[4] It grows on sandy soils in open eucalyptus forest or woodland. or heathland.[2]

Ecology

Isopogon ceratophyllus is extremely sensitive to dieback (infection by the pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi). Fieldwork in the Brisbane Ranges in 1994 showed that I. ceratophyllus, which had been common in areas before dieback and had vanished along with other sensitive species, had yet to return after 30 years. This was despite other sensitive species, such as grasstree (Xanthorrhoea australis), smooth parrot-pea (Dillwynia glaberrima), erect guinea flower (Hibbertia stricta) and prickly broom heath (Monotoca scoparia), eventually regenerating around 10 years post-infection.[11] All Tasmanian populations are at risk of eradication by P. cinnamomi. Plants are perishing at Wingaroo Nature Reserve on Flinders Island from exposure to the pathogen.[12]

Cultivation

Rarely cultivated, it is slow growing and requires well-drained yet moist sandy soils.[13] It would suit a rockery garden.[4]

References

- 1 2 "Isopogon ceratophyllus". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- 1 2 3 "Isopogon ceratophyllus R.Br". Flora of Australia Online. Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government.

- ↑ Brown, Robert (1810). "On the Proteaceae of Jussieu". Transactions of the Linnean Society. 10: 72.

- 1 2 3 4 Wrigley, John; Fagg, Murray (1991). Banksias, Waratahs and Grevilleas. Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. p. 430. ISBN 0-207-17277-3.

- 1 2 Erickson, Robert F. "Kuntze, Otto (1843–1907)". Botanicus.org. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Knight, Joseph (1809). On the Cultivation of the Plants Belonging to the Natural Order of Proteeae. London, United Kingdom: W. Savage. p. 94.

- ↑ Hooker, William (1805). The Paradisus Londinensis. Vol. 1. London, United Kingdom: D. N. Shury.

- ↑ Kuntze, Otto (1891). Revisio generum plantarum:vascularium omnium atque cellularium multarum secundum leges nomenclaturae internationales cum enumeratione plantarum exoticarum in itinere mundi collectarum. Leipzig, Germany: A. Felix. p. 578. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- ↑ "Congrès international de Botanique de Vienne". Bulletin de la Société botanique de France. 52: LIII. 1905.

- ↑ Natural and Cultural Heritage Division (3 September 2003). "Isopogon ceratophyllus" (PDF). Threatened Flora of Tasmania. Hobart: Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ↑ Weste, Gretna; Ashton, David H. (1994). "Regeneration and Survival of Indigenous Dry Sclerophyll Species in the Brisbane Ranges, Victoria, After a Phytophthora cinnamomi Epidemic". Australian Journal of Botany. 42 (2): 239–53. doi:10.1071/BT9940239.

- ↑ Natural and Cultural Heritage Division (2014). Flinders Island Natural Values Survey 2012 (PDF). Hobart: Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-9922694-3-2.

- ↑ Walters, Brian (November 2007). "Isopogon ceratophyllus". ANPSA website. Australian Native Plants Society (Australia). Retrieved 25 December 2015.