Some Italian immigrants in the Casa Italia of San José, in the first half of the 20th century. | |

| Total population | |

| c. 2,300 (by birth)[1] c. 380,000 (by ancestry, 7.5% of Costa Rica's population)[2][3] | |

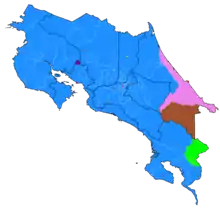

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Coto Brus Canton · San José | |

| Languages | |

| Costa Rican Spanish · Italian and Italian dialects | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Italians, Italian Americans, Italian Argentines, Italian Bolivians, Italian Brazilians, Italian Canadians, Italian Chileans, Italian Colombians, Italian Cubans, Italian Dominicans, Italian Ecuadorians, Italian Guatemalans, Italian Haitians, Italian Hondurans, Italian Mexicans, Italian Panamanians, Italian Paraguayans, Italian Peruvians, Italian Puerto Ricans, Italian Salvadorans, Italian Uruguayans, Italian Venezuelans |

Italian Costa Ricans (Italian: italo-costaricani; Spanish: ítalo-costarricenses) are Costa Rican-born citizens who are fully or partially of Italian descent, whose ancestors were Italians who emigrated to Costa Rica during the Italian diaspora, or Italian-born people in Costa Rica. Most of them reside in San Vito, the capital city of the Coto Brus Canton. Both Italians and their descendants are referred to in the country as tútiles.[4][5] There were over 380,000 Costa Ricans of Italian descent,[2][3] corresponding to about 7.5% of Costa Rica's population, while there were around 2,300 Italian citizens.[1]

History

After Christopher Columbus's discovery of Costa Rica in 1502, only a few Italians—initially mostly from the Republic of Genoa—moved to live in the Costa Rica region. The italo-costarican historian Rita Bariatti named Girolamo Benzomi, Stefano Corti, Antonio Chapui, Jose Lombardo,[6] Francesco Granado, and Benito Valerino are between those who created important families in colonial Costa Rica.[7] In the 1883 census of Costa Rica there were only 63 Italian citizens and most of them lived in the San José area, but soon in 1888 there were 1,433 Italians working mainly in the creation of new railways.

In 1888, the railroad brought in laborers from Italy as an alternative workforce.[8] The harsh work conditions prompted them to leave the railroad project although many remained in Costa Rica, settling in a government-sponsored colony known as San Vito in the Southern Pacific region.

However, one third of those Italian workers of the railways remained in Costa Rica and created a small but important community.[9]

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Italian community grew in importance, even because some Italo-costaricans reached top levels in the political arena. Julio Acosta García, a descendant from a Genoese family in San Jose since colonial times, served as President of Costa Rica from 1920 to 1924. In 1939 there were nearly 15,000 Italians resident in Costa Rica and many suffered persecutions during World War II[10]

In 1952, there was an influx of Italian immigrants, mainly farmers, who arrived in San Vito armed with tractors and other farm machinery, and began to farm the land intensively and to raise cattle. An Italian organization for agricultural colonization purchased 10,000 hectares of land from the government of Costa Rica.[11]

Indeed in the 1950s a group of 500 Italian colonists settled in the area of San Vito (that received this name as an homage to San Vito, an Italian saint).[12]

In 1952, in the midst of the post-war socio-economic crisis in Europe, the two brothers Ugo and Vito Sansonetti organised a group of Italian pioneers from 40 different places, from Trieste to Taranto, and including a handful from Istria (Istrian Italians) and Dalmatia (Dalmatian Italians), with the latter arriving during the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus.

This Italian immigration is a typical example of directed agricultural colonisation, similar in many ways to the process in other places in Latin America. The European immigrants were helped by the Comité Intergubernamental para las Migraciones Europeas (CIME), (Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration).

Vito Sansonetti, a seaman by profession, was the founder of the colonising company which he named Sociedad Italiana de Colonización Agricola (SICA), (Italian Agricultural Colonisation Society), and was in charge of negotiations with the Costa Rican authorities represented by the Instituto de Tierras y Colonización (ITCO) (Institute of Land and Colonisation).

San Vito is the only place in Costa Rica (other than some small communities) in which the teaching of the Italian language is compulsory in the educational system, and promoted by the Ministerio de Educación Pública (Ministry of Public Education) in order to preserve Italian customs and traditions. Additionally there is an Italian cultural center in San Vito, as well as several Italian restaurants. The Italian language is still usually spoken only by the older citizens of San Vito, even if many young people have some superficial knowledge.

Culture

There are many Italian related institutions and cultural associations in Costa Rica. The historical core of the Italian community in Costa Rica is the city of San José, which received the largest number of Italian immigrants in all of Central America. Nowadays, the capital still has this centralized role for the local Italians, since it shelters the majority of the Italian citizens (and their descendants) residing in the country, although other communities also gather a considerable number of immigrants, such as San Vito.

In 1890, the Italian Philanthropic Society (Italian: Società Filantropica Italiana) was created only two years after the first mass immigration from Lombardy and Northern Italy. It would then evolve in several Italian Organizations of Mutual Aid until 1902, when the massive immigration from Southern Italy began. Shortly thereafter, the Italian Society of Mutual Help (Italian: Associazione Italiana di Mutuo Soccorso, Spanish: Asociación italiana de mutuo socorro) was created.

In addition, the capital saw the inauguration of cultural centers such as the Italian Club in 1904, the Italian Center in 1905, and later the "Casa d'Italia" in the second half of the 20th century. In 1897, Italian engineer Cristoforo Molinari created the Teatro Nacional de Costa Rica, that is considered the finest historic building in the capital, also known for its exquisite interior, which includes lavish Italian furnishings.[13]

Many Italian cultural and educational institutions were established in the country. Among them, many schools, the main one being the Dante Alighieri Society, established in 1932, which has four venues in the country.[14] Also, the Bologna Institute and the Italy-Costa Rica Cultural Center are important in the capital.

Furthermore, in the small city of San Vito, where 3,000 of the 5,000 inhabitants are descendants of Italian colonists, the "Centro Cultural Dante Alighieri" (Dante Alighieri Cultural Centre) offers historical information on the Italian immigration. There is an Italian "meeting" center in San Vito's Catholic church, as well as several Italian restaurants.

In San Vito, the Liceo Bilingüe Ítalo-Costarricense teaches the Italian language as an official compulsory subject.[15] The Italian language is usually spoken by some of the older citizens of San Vito who moved from Italy in the 1950s.

Italian language in Costa Rica

Costa Rica is the Central American country with the largest Italian-speaking community. Apart from San Jose, the area with the greatest presence of speakers is the Southern Zone, especially in the cantons of Coto Brus and Corredores, where there are communities like San Vito that were colonized by Italian immigrants and where the language is still spoken actively, with a majority of Sardinian, Calabrian and Sicilian varieties. Furthermore, in these communities of Coto Brus,[16] the Italian language is taught in regional public education, and throughout the country there are many schools that also teach the language as an optional subject.[17]

Also noteworthy is the lasting southern influence in certain phonetic and lexical aspects of Costa Rican Spanish. Among the Italian linguistic inheritances, the best known is the pronunciation of the "r" and "rr", which the majority of the population pronounces as a deaf alveolar rhithic fricative, as do the Sicilians. In modern Costa Rican slang, a multitude of Italianisms also exist such as acois (from the echo: here), birra (from the beer: beer), bochinche (fight, disorder), capo (someone outstanding), bell (from it: bell jergal: spy, means to watch), canear (from the "canne: police baton, means to be in jail"), "chao" (from the "ciao: goodbye"), facha (from "faccia": "face, used when someone is badly dressed"), used when someone is poorly arranged) and sound (from the suonare: sound, means to fail or hit), among many others.

Cuisine

Due to the influence of immigrants, Costa Rican cuisine has received notable contributions from Italian cuisine, which is still highly regarded and is mainly presented in the Costa Rican Central Valley and San Vito. Likewise, Creole dishes typical of the Italians in Costa Rica were created, adapting to the local food availability.[18]

Within the Italian-Costa Rican cuisine, pastas stand out as an integral part of their eating habits. Pastas have been known in the country since colonial times, but it was only with the massive wave of immigrants that their popularity increased in the Creole diet, as with the arrival of the Italians numerous recipes for preparing them, and in turn the number of varieties available for sale has increased significantly.

Today, many of the pasta recipes have become favorite Costa Rican Creole dishes, with Costa Rica being one of the largest pasta consumers on the planet.[19] Macaroni is overwhelmingly the most popular, mainly those eaten with achiote, tomato, and diced pork. Other favorite dishes of Italian origin are spaghetti soup, fettuccine, gnocchi, tagliatelle, calzone, cannelloni and lasagna. Many of these pastas would achieve such a strong cohesion that they are now an integral part of casado, the country's most traditional dish.[20]

Pizza also exists in Costa Rica in countless varieties; the traditional Italian, American Creole, with different types of pasta, by the meter and filled, among many others. These are sold in another huge variety of establishments; from large commercial franchises to village pizzerias. Costa Rican pizza is made with Creole cheese and tomatoes; minced meat, ham, onion, olives and sweet pepper. In Costa Rica, focaccia is also commonly eaten.

There is also a varied production of Italian-type Creole cheeses. The centerpiece is the palmito cheese, which is basically mozzarella-style, made with whole milk in the form of a stringy paste. Its taste is slightly salty and has some acidity due to the maturation.[21]

As for the consumption of desserts, they are quite common: gelato, Neapolitan ice cream, tiramisu, cannoli, biscotti and, during the Christmas period, panettone. Additionally, a multitude of Italian wines and spirits are consumed.

Notable people

- Julio Acosta García - Costa Rican President (1920–1924)

- Jorge Rossi Chavarria - Costa Rican politician

- Carlos Gagini - Costa Rican intellectual, philologist writer and linguist

- Bruno Stagno Ugarte - Costa Rican Minister of Foreign Affairs and ambassador

- Lola Castegnaro - Costa Rican conductor, composer and music educator

- Erick Cabalceta - Costa Rican footballer

- Anacristina Rossi - Costa Rican writer

- Giannina Facio - Costa Rican actress

- Eunice Odio - Costa Rican poet

- Francisco Amighetti - Costa Rican painter

- Maria Eugenia Bozzoli - Costa Rican anthropologist, sociologist and human rights activist

- Margarita Bertheau - Costa Rican painter and cultural promoter

- Daniel Zovatto - Costa Rican actor

- Rodrigo Carazo Odio - Costa Rican President (1978–1982)

- Bruno Stagno Ugarte - Costa Rican politician

- Francisco Dall'Anese - Costa Rican politician

- Alfio Piva - Costa Rican scientist and politician

- Brandon Poltronieri - Costa Rican footballer

- Marvin Loría - Costa Rican footballer

- Geovanny Jara - Costa Rican footballer

- José Miguel Cubero - Costa Rican footballer

References

- 1 2 Inec — Sección de Estadística Archived 27 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. INEC.

- 1 2 "Costa Rica e Italia: Países unidos por la historia y la cultura". Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- 1 2 "La inmigración italiana en Costa Rica. Primera Parte: Prologo". Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ↑ Agüero Chaves, Arturo (1996). Diccionario de costarriqueñismos (PDF). San José, Costa Rica: Legislative Assembly of Costa Rica. p. 322. ISBN 9977-916-55-1. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ↑ Mejía Mejía, Francisco (2019). Francisco Mejía Mejía: La autobiografía de un campesino costarricense, 1923-1981 (PDF). San José: University of Costa Rica. p. 264. ISBN 978-9930-9585-1-3. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ↑ Carmela Velazquez: Chapui-Corti-Lombardo

- ↑ "Rita Bariatti: La immigacion esporadica durante la epoca colonial (La inmigracion italiana en Costa Rica, segunda parte)". Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ "Costa Rica's Culture & People - The Italians". itravel-costarica.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2010.

- ↑ "Rita Bariatti: El flujo migratorio masivo (La inmigracion italiana en Costa Rica, cuarta parte)". Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ Italians in Costa Rica internment camps

- ↑ "San Vito, Costa Rica Vacations". travelwizard.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008.

- ↑ Italians of San Vito (in Italian)

- ↑ Baker, C.P. (2005). Costa Rica. Dorling Kindersley Eye Witness Travel Guides. p. 60.

- ↑ History: Dante Alighieri Society "Our-history". Editor Dante Alighieri Cultural Association in Costa Rica (http://www.dantecostarica.org)

- ↑ Colegio Italo-Costarricense

- ↑ Sansonetti V. (1995) Quemé mis naves en esta montaña: La colonización de la altiplanicie de Coto Brus y la fundación de San Vito de Java. Jiménez y Tanzi. San José, Costa Rica

- ↑ San Vito, un pueblo de Italianos emigrados (in Spanish)

- ↑ "Esta semana en 'Revista Dominical': Los 65 años de San Vito, un pueblo de migrantes". Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ↑ "Consumo de la pasta en el mundo - Consumo national de la pasta 2011 (tonnes)". Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "El Sabor de Italia en Costa Rica". 24 June 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ↑ "Queso palmito: originalmente costarricense". Retrieved 19 September 2018.

Bibliography

- Bariatti, Rita. La inmigración italiana en Costa Rica. Revista Acta Académica. Universidad de Centro América. San José, 1997 ISSN 1017-7507

- Cappelli, Vittorio. "Nelle altre Americhe", in Storia dell'emigrazione italiana. Arrivi, a cura di P. Bevilacqua, A. De Clementi, E. Franzina. Donzelli. Roma, 2002.

- Cappelli, Vittorio. Nelle altre Americhe. Calabresi in Colombia, Panamà, Costa Rica e Guatemala. La Mongolfiera. Doria di Cassano Jonio, 2004.

- Liano, Dante. Dizionario biografico degli Italiani in Centroamerica. Editore Vita e Pensiero. Milano, 2003 ISBN 8834309790 ()