A young Italian exile on the run carries, along with her personal effects, a flag of Italy (1945). | |

| Date | 1943–1960 |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Cause | The Treaty of Peace with Italy, signed after the Second World War, assigned the former Italian territories of Istria, Kvarner, the Julian March, and Dalmatia to the nation of Yugoslavia |

| Participants | Local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), as well as ethnic Slovenes and Croats who chose to maintain Italian citizenship. |

| Outcome | Between 230,000 and 350,000 people emigrated from Yugoslavia to Italy and, in a smaller number, towards the Americas, Australia and South Africa.[1][2] |

| Part of a series on |

| Aftermath of World War II in Yugoslavia |

|---|

| Main events |

| Massacres |

| Camps |

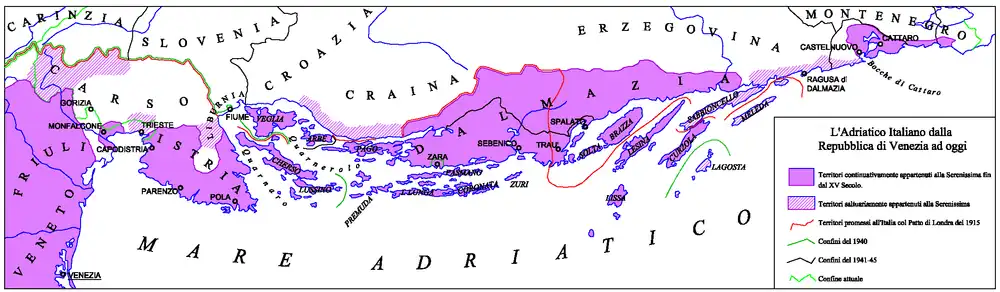

The Istrian–Dalmatian exodus (Italian: esodo giuliano dalmata; Slovene: istrsko-dalmatinski eksodus; Croatian: istarsko-dalmatinski egzodus) was the post-World War II exodus and departure of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) as well as ethnic Slovenes and Croats from Yugoslavia. The emigrants, who had lived in the now Yugoslav territories of the Julian March (Karst Region and Istria), Kvarner and Dalmatia, largely went to Italy, but some joined the Italian diaspora in the Americas, Australia and South Africa.[1][2] These regions were ethnically mixed, with long-established historic Croatian, Italian, and Slovene communities. After World War I, the Kingdom of Italy annexed Istria, Kvarner, the Julian March and parts of Dalmatia including the city of Zadar. At the end of World War II, under the Allies' Treaty of Peace with Italy, the former Italian territories in Istria, Kvarner, the Julian March and Dalmatia were assigned to the nation of Yugoslavia, except for the Province of Trieste. The former territories absorbed into Yugoslavia are part of present-day Croatia and Slovenia.

According to various sources, the exodus is estimated to have amounted to between 230,000 and 350,000 Italians (the others being ethnic Slovenes and Croats who chose to maintain Italian citizenship)[3] leaving the areas in the aftermath of the conflict.[4][5] The exodus started in 1943 and ended completely only in 1960. According to the census organized in Croatia in 2001 and that organized in Slovenia in 2002, the Italians who remained in the former Yugoslavia amounted to 21,894 people (2,258 in Slovenia and 19,636 in Croatia).[6][7]

Hundreds up to tens of thousands of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) were killed or summarily executed during World War II by Yugoslav Partisans and OZNA during the first years of the exodus, in what became known as the foibe massacres.[8][9] From 1947, after the war, Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians were subject by Yugoslav authorities to less violent forms of intimidation, such as nationalization, expropriation, and discriminatory taxation,[10] which gave them little option other than emigration.[11][12][13]

Overview of the exodus

A Romance-speaking population has existed in Istria since the fall of the Roman Empire, when Istria was fully Latinised. The coastal cities especially had Italian populations, connected to other areas through trade, but the interior was mostly Slavic, especially Croatian.[14]

Istrian Italians were more than 50% of the total population for centuries,[15] while making up about a third of the population in 1900.[16] According to the 1910 Austrian census, out of 404,309 inhabitants in Istria, 168,116 (41.6%) spoke Croatian, 147,416 (36.5%) spoke Italian, 55,365 (13.7%) spoke Slovene, 13,279 (3.3%) spoke German, 882 (0.2%) spoke Romanian (actually Istro-Romanian), 2,116 (0.5%) spoke other languages and 17,135 (4.2%) were non-citizens, who had not been asked for their language of communication. (Istria at the time included parts of the Karst and Liburnia). So, in the peninsula of Istria before World War I, local ethnic Italians accounted for about a third (36.5%) of the local inhabitants.[17] Furthermore, the nearly complete disappearance of the Dalmatian Italians (there were 92,500 or nearly 33% of the total Dalmatian population in 1803,[18][19] while now there are only 300) has been related to democide and ethnic cleansing by scholars like R. J. Rummel.

A new wave of Italians, who were not part of the indigenous Venetian-speaking Istrians, arrived between 1918 and 1943. At the time, Primorska and Istria, Rijeka, part of Dalmatia, and the islands of Cres, Lastovo, and Palagruža (and, from 1941 to 1943, Krk) were considered part of Italy. The Kingdom of Italy's 1936 census[20] indicated approximately 230,000 people who listed Italian as their language of communication in what is now the territory of Slovenia and Croatia, then part of the Italian state (ca. 194,000 in today's Croatia and ca. 36,000 in today's Slovenia).

From the end of World War II until 1953, according to various data, between 250,000 and 350,000 people emigrated from these regions. Since the Italian population before World War II numbered 225,000 (150,000 in Istria and the rest in Fiume/Rijeka and Dalmatia), the remainder must have been Slovenes and Croats, if the total was 350,000. According to Matjaž Klemenčič, one-third were Slovenes and Croats who opposed the Communist government in Yugoslavia,[21] but this is disputed. Two-thirds were local ethnic Italians, emigrants who were living permanently in this region on 10 June 1940 and who expressed their wish to obtain Italian citizenship and emigrate to Italy. In Yugoslavia they were called optanti (opting ones) and in Italy were known as esuli (exiles). The emigration of Italians reduced the total population of the region and altered its historical ethnic structure.[22]

In 1953, there were 36,000 declared Italians in Yugoslavia, just 16% of the 225,000 Italians before World War II.[21]

History

Early history

Via conquests, the Republic of Venice, between the 9th century and 1797, extended its dominion to coastal parts of Istria and Dalmatia.[23] Thus Venice invaded and attacked Zadar multiple times, especially devastating the city in 1202 when Venice used the crusaders, on their Fourth Crusade, to lay siege, then ransack, demolish and rob the city,[24] the population fleeing into countryside. Pope Innocent III excommunicated the Venetians and crusaders for attacking a Catholic city.[24] The Venetians used the same Crusade to attack the Dubrovnik Republic, and force it to pay tribute, then continued to sack Christian Orthodox Constantinople where they looted, terrorized, and vandalized the city, killing 2.000 civilians, raping nuns and destroying Christian Churches, with Venice receiving a big portion of the plundered treasures.

The coastal areas and cities of Istria came under Venetian Influence in the 9th century. In 1145, the cities of Pula, Koper and Izola rose against the Republic of Venice but were defeated, and were since further controlled by Venice.[25] On 15 February 1267, Poreč was formally incorporated with the Venetian state.[26] Other coastal towns followed shortly thereafter. The Republic of Venice gradually dominated the whole coastal area of western Istria and the area to Plomin on the eastern part of the peninsula.[25] Dalmatia was first and finally sold to the Republic of Venice in 1409 but Venetian Dalmatia wasn't fully consolidated from 1420.[27]

From the Middle Ages onwards numbers of Slavic people near and on the Adriatic coast were ever increasing, due to their expanding population and due to pressure from the Ottomans pushing them from the south and east.[28][29] This led to Italic people becoming ever more confined to urban areas, while the countryside was populated by Slavs, with certain isolated exceptions.[14] In particular, the population was divided into urban-coastal communities (mainly Romance-speakers) and rural communities (mainly Slavic-speakers), with small minorities of Morlachs and Istro-Romanians.[30]

Republic of Venice influenced the neolatins of Istria and Dalmatia until 1797, when it was conquered by Napoleon: Capodistria and Pola were important centers of art and culture during the Italian Renaissance.[31] From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, Italian and Slavic communities in Istria and Dalmatia had lived peacefully side by side because they did not know the national identification, given that they generically defined themselves as "Istrians" and "Dalmatians", of "Romance" or "Slavic" culture.[32]

Austrian Empire

After the fall of Napoleon (1814), Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia were annexed to the Austrian Empire.[33] Many Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy.[34] However, after the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria and Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic. This triggered the gradual rise of Italian irredentism among many Italians in Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia, who demanded the unification of the Julian March, Kvarner and Dalmatia with Italy. The Italians in Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia supported the Italian Risorgimento: as a consequence, the Austrians saw the Italians as enemies and favored the Slav communities of Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia.[35]

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[36]

His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard. His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.

Istrian Italians were more than 50% of the total population of Istria for centuries,[15] while making up about a third of the population in 1900.[16] Dalmatia, especially its maritime cities, once had a substantial local ethnic Italian population (Dalmatian Italians), making up 33% of the total population of Dalmatia in 1803,[18][19] but this was reduced to 20% in 1816.[38] According to Austrian census, the Dalmatian Italians formed 12.5% of the population in 1865.[39] In the 1910 Austro-Hungarian census, Istria had a population of 57.8% Slavic-speakers (Croat and Slovene), and 38.1% Italian speakers.[40] For the Austrian Kingdom of Dalmatia, (i.e. Dalmatia), the 1910 numbers were 96.2% Slavic speakers and 2.8% Italian speakers.[41] In 1909 the Italian language lost its status as the official language of Dalmatia in favor of Croatian only (previously both languages were recognized): thus Italian could no longer be used in the public and administrative sphere.[42]

World War I and post-War period

In 1915, Italy abrogated its alliance and declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire,[43] leading to bloody conflict mainly on the Isonzo and Piave fronts. Britain, France and Russia had been "keen to bring neutral Italy into World War I on their side. However, Italy drove a hard bargain, demanding extensive territorial concessions once the war had been won".[44] In a deal to bring Italy into the war, under the London Pact, Italy would be allowed to annex not only Italian-speaking Trentino and Trieste, but also German-speaking South Tyrol, Istria (which included large non-Italian communities), and the northern part of Dalmatia including the areas of Zadar (Zara) and Šibenik (Sebenico). Mainly Italian Fiume (present-day Rijeka) was excluded.[44]

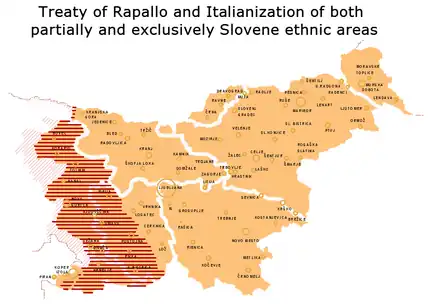

After the war, the Treaty of Rapallo between the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) and the Kingdom of Italy (12 November 1920), Italy annexed Zadar in Dalmatia and some minor islands, almost all of Istria along with Trieste, excluding the island of Krk, and part of Kastav commune, which mostly went to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. By the Treaty of Rome (27 January 1924), the Free State of Fiume (Rijeka) was divided between Italy and Yugoslavia.[45]

Between 31 December 1910, and 1 December 1921, Istria lost 15.1% of its population. The last survey under the Austrian empire recorded 404,309 inhabitants, which dropped to 343,401 by the first Italian census after the war.[46] While the decrease was certainly related to World War I and the changes in political administration, emigration also was a major factor. In the immediate post World War I period, Istria saw an intense migration outflow. Pula, for example, was badly affected by the drastic dismantling of its massive Austrian military and bureaucratic apparatus of more than 20,000 soldiers and security forces, as well as the dismissal of the employees from its naval shipyard. A serious economic crisis in the rest of Italy forced thousands of Croat peasants to move to Yugoslavia, which became the main destination of the Istrian exodus.[46]

Due to a lack of reliable statistics, the true magnitude of Istrian emigration during that period cannot be assessed accurately. Estimates provided by varying sources with different research methods show that about 30,000 Istrians migrated between 1918 and 1921.[46] Most of them were Austrians, Hungarians and Slavic citizens who used to work for the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[47]

Slavs under Italian Fascist rule

After World War I, under the Treaty of Rapallo between the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Kingdom of Yugoslavia) and the Kingdom of Italy (12 November 1920), Italy obtained almost all of Istria with Trieste, the exception being the island of Krk and part of Kastav commune, which went to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. By the Treaty of Rome (27 January 1924) Italy took Rijeka as well, which had been planned to become an independent state.

In these areas, there was a forced policy of Italianization of the population in the 1920s and 1930s.[48] In addition, there were acts of fascist violence not hampered by the authorities, such as the torching of the Narodni dom (National House) in Pula and Trieste carried out at night by Fascists with the connivance of the police (13 July 1920). The situation deteriorated further after the annexation of the Julian March, especially after Benito Mussolini came to power (1922). In March 1923 the prefect of the Julian March prohibited the use of Croatian and Slovene in the administration, whilst their use in law courts was forbidden by Royal decree on 15 October 1925.

The activities of Croatian and Slovenian societies and associations (Sokol, reading rooms, etc.) had already been forbidden during the occupation, but specifically so later with the Law on Associations (1925), the Law on Public Demonstrations (1926) and the Law on Public Order (1926). All Slovenian and Croatian societies and sporting and cultural associations had to cease every activity in line with a decision of provincial fascist secretaries dated 12 June 1927. On a specific order from the prefect of Trieste on 19 November 1928 the Edinost political society was also dissolved. Croatian and Slovenian co-operatives in Istria, which at first were absorbed by the Pula or Trieste Savings Banks, were gradually liquidated.[49]

At the same time, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia attempted a policy of forced Croatisation against the Italian minority in Dalmatia.[50] The majority of the Italian Dalmatian minority decided to transfer in the Kingdom of Italy.[51]

World War II

Following the Wehrmacht invasion of Yugoslavia (6 April 1941), the Italian zone of occupation was further expanded.[53] Italy annexed large areas of Croatia (including most of coastal Dalmatia) and Slovenia (including its capital Ljubljana).[54]

Helped by the Ustaše, a Croatian fascist movement animated by Catholicism and ultranationalism, the Italian occupation continued its repression of Partisan activities and the killing and imprisonment of thousands of Yugoslav civilians in concentration camps (such as the Rab concentration camp) in the newly annexed provinces. This increased the anti-Italian sentiments of the Slovenian and Croatian subjects of Fascist Italy.

During the Italian occupation until its capitulation in September 1943, the population was subjected to atrocities described by Italian historian Claudio Pavone as "aggressive and violent. Not so much an eye for an eye as a head for an eye"; atrocities were often carried out with the help of the Ustaše.[55]

After World War II, there were large-scale movements of people choosing Italy rather than continuing to live in communist Yugoslavia. In Yugoslavia, the people who left were called optanti, which translates as 'choosers'; they call themselves esuli or exiles. Their motives included fear of reprisals, as well as economic and ethnic persecution.[56]

Events of 1943

When the Fascist regime collapsed in 1943 reprisals against Italian fascists took place. Several hundred Italians were killed by Josip Broz Tito's resistance movement in September 1943; some had been connected to the fascist regime, while others were victims of personal hatred or the attempt of the Partisan resistance to get rid of its real or supposed enemies.[57]

The Foibe massacres

Between 1943 and 1947, the exodus was bolstered by a wave of violence, known as the "Foibe massacres", mainly committed by OZNA and Yugoslav Partisans in Julian March (Karst Region and Istria), Kvarner and Dalmatia, against the local ethnic Italian population (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), as well against anti-communists in general (even Croats and Slovenes), usually associated with Fascism, Nazism and collaboration with Axis,[8][58] and against real, potential or presumed opponents of Tito communism.[59] The type of attack was state terrorism,[8][60] reprisal killings,[8][61] and ethnic cleansing against Italians.[8][9][62][63][64]

The mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission, established in 1995 by the two governments to investigate these matters, described the circumstances of the 1945 killings:

14. These events were triggered by the atmosphere of settling accounts with the fascists; but, as it seems, they mostly proceeded from a preliminary plan which included several tendencies: endeavors to remove persons and structures who were in one way or another (regardless of their personal responsibility) linked with Fascism, with the Nazi supremacy, with collaboration and with the Italian state, and endeavors to carry out preventive cleansing of real, potential or only alleged opponents of the communist regime, and the annexation of the Julian March to the new SFR Yugoslavia. The initial impulse was instigated by the revolutionary movement, which was changed into a political regime and transformed the charge of national and ideological intolerance between the partisans into violence at the national level.

The Yugoslav partisans intended to kill whoever could oppose or compromise the future annexation of Italian territories: as a preventive purge of real, potential or presumed opponents of Tito communism[59] (Italian, Slovenian and Croatian anti-communists, collaborators and radical nationalists), the Yugoslav partisans also exterminated the native anti-fascist autonomists — including the leadership of Italian anti-fascist partisan organizations and the leaders of Fiume's Autonomist Party, like Mario Blasich and Nevio Skull, who supported local independence from both Italy and Yugoslavia — for example in the city of Fiume, where at least 650 were killed after the entry of the Yugoslav units, without any due trial.[65][66]

The term refers to the victims who were often thrown alive into foibas[67] (deep natural sinkholes; by extension, it also was applied to the use of mine shafts, etc., to hide the bodies). In a wider or symbolic sense, some authors used the term to apply to all disappearances or killings of Italian people in the territories occupied by Yugoslav forces. They excluded possible 'foibe' killings by other parties or forces. Others included deaths resulting from the forced deportation of Italians, or those who died while trying to flee from these contested lands.

The estimated number of people killed in the foibe is disputed, varying from hundreds to thousands,[68] according to some sources 11,000[58][69] or 20,000.[8] The Italian historian, Raoul Pupo estimates 3,000 to 4,000 total victims, across all areas of former Yugoslavia and Italy from 1943 to 1945,[70] with the primary target being military and repressive forces of the Fascist regime, and civilians associated with the regime, including Slavic collaborators.[71] He places the events in the broader context of "the collapse of a structure of power and oppression: that of the fascist state in 1943, that of the Nazi-fascist state of the Adriatic coast in 1945".[71] The foibe massacres were followed by the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus.[72]

The exodus

Economic insecurity, ethnic hatred and the international political context that eventually led to the Iron Curtain resulted in up to 350,000 people, mostly Italians, choosing to leave Istria (and even Dalmatia and northern Julian March).[5][73]

The exiles were to be given compensation for their loss of property and other indemnity by the Italian state under the terms of the peace treaties, but in the end did not receive anything. The exiles having fled intolerable conditions in their homeland on the promise of aid in the Italian homeland, were herded together in former concentration camps and prisons. Exiles also encountered hostility from those Italians who viewed them as taking away scarce food and jobs.[74] Following the exodus, the areas were settled with Yugoslav people.

In a 1991 interview with the Italian magazine Panorama, prominent Yugoslav political dissident Milovan Đilas claimed to have been dispatched to Istria alongside Edvard Kardelj in 1946, to organize anti-Italian propaganda. He stated it was seen as "necessary to employ all kinds of pressure to persuade Italians to leave", due to their constituting a majority in urban areas.[75] Although he was stripped of his offices in 1954, in 1946 Đilas was a high-ranking Yugoslav politician: a member of the Yugoslav Communist Party's Central Committee, in charge of its department of propaganda.

During the years 1946 and 1947 there was also a counter-exodus. In a gesture of comradeship hundreds of Italians Communists workers from the city of Monfalcone and Trieste, moved to Yugoslavia and more precisely to the shipyards of Rijeka taking the place of the departed Italians. They viewed the new Yugoslavia of Tito as the only place where the building of socialism was possible. They were soon bitterly disappointed. They were accused of deviationism by the Yugoslav Regime and some were deported to concentration camps.[76]

The Italian bishop of the Catholic diocese of Poreč and Pula Raffaele Radossi was replaced by Slovene Mihovil Toroš on 2 July 1947.[77] In September 1946 while Bishop Radossi was in Žbandaj officiating a confirmation local activists surrounded him in a Partisan kolo dance.[78]

Bishop Radossi subsequently moved from the bishop's residence in Poreč to Pula, which was under a joint United Kingdom-United States Allied Administration at the time. He officiated his last confirmation in October 1946 in Filipana where he narrowly avoided an attack by a group of thugs.[78] The Bishop of Rijeka, Ugo Camozzo, also left for Italy on 3 August 1947.[79]

Periods of the exodus

The exodus took place between 1943 and 1960, with the main movements of population having place in the following years:

- 1943

- 1945

- 1947

- 1954

The first period took place after the surrender of the Italian army and the beginning of the first wave of anti-fascist violence. The Wehrmacht was engaged in a front-wide retreat from the Yugoslav Partisans, along with the local collaborationist forces (the Ustaše, the Domobranci, the Chetniks, and units of Mussolini's Italian Social Republic). The first city to see a massive departure of local ethnic Italians was Zadar. Between November 1943 and Zadar was bombed by the Allies, with serious civilian casualties (fatalities recorded range from under 1,000 to as many as 4,000 of over 20,000 city's inhabitants). Many died in carpet bombings. Many landmarks and centuries old works of art were destroyed. A significant number of civilians fled the city.[80]

In late October 1944 the German army and most of the Italian civilian administration abandoned the city.[81] On 31 October 1944, the Partisans seized the city, until then a part of Mussolini's Italian Social Republic. At the start of World War II, Zadar had a population of 24,000 and, by the end of 1944, this had decreased to 6,000.[81] Formally, the city remained under Italian sovereignty until 15 September 1947 but by that date the exodus from the city had been already almost total (Paris Peace Treaties).[82]

A second wave left at the end of the war with the beginning of killings, expropriation and other forms of pressure from the Yugoslavs authorities to establish control.[11][83]

On 2–3 May 1945, Rijeka was occupied by vanguards of the Yugoslav Army. Here more than 500 collaborators, Italian military and public servants were summarily executed; the leaders of the local Autonomist Party, including Mario Blasich and Nevio Skull, were also murdered. By January 1946, more than 20,000 people had left the province.[84]

After 1945, the departure of the local ethnic Italians was bolstered by events of less violent nature. According to the American historian Pamela Ballinger:[10]

After 1945 physical threats generally gave way to subtler forms of intimidation such as the nationalization and confiscation of properties, the interruption of transport services (by both land and sea) to the city of Trieste, the heavy taxation of salaries of those who worked in Zone A and lived in Zone B, the persecution of clergy and teachers, and economic hardship caused by the creation of a special border currency, the Jugolira.

The third part of the exodus took place after the Paris peace treaty, when Istria was assigned to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, except for a small area in the northwest part that formed the independent Free Territory of Trieste. The coastal city of Pula was the site of the large-scale exodus of its Italian population. Between December 1946 and September 1947, Pula almost completely emptied as its residents left all their possessions and "opted" for Italian citizenship. 28,000 of the city's population of 32,000 left. The evacuation of the residents has been organized by Italian civil and Allied military authorities in March 1947, in anticipation of the city's passage from the control of the Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories to the Yugoslav rule, scheduled for September 1947.[85][86]

The fourth period took place after the Memorandum of Understanding in London. It gave provisional civil administration of Zone A (with Trieste), to Italy, and Zone B to Yugoslavia. Finally, in 1975 the Treaty of Osimo officially divided the former Free Territory of Trieste between Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Italian Republic.[87]

Estimates of the exodus

Several estimates of the exodus by historians:

- Vladimir Žerjavić (Croat), 191,421 Italian exiles from Croatian territory.

- Nevenka Troha (Slovene), 40,000 Italian and 3,000 Slovene exiles from Slovenian territory.

- Raoul Pupo (Italian), about 250,000 Italian exiles

- Flaminio Rocchi (Italian), about 350,000 Italian exiles

The mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission verified 27,000 Italian and 3,000 Slovene migrants from Slovenian territory. After decades of silence from the Yugoslav authorities (the history of the Istrian Exodus remained a tabooed topic in Yugoslav public discourse), Tito himself would declare in 1972 during a speech in Montenegro that three hundred thousands Istrians had left the peninsula after the war.[88]

Famous exiles

Those whose families left Istria or Dalmatia in the post-World War II period include:

- Alida Valli, film actress

- Mario Andretti, racing driver

- Lidia Bastianich, chef

- Nino Benvenuti, boxer: three times professional world's champion and Olympic gold medalist[89]

- Enzo Bettiza, novelist, journalist and politician

- Oretta Fiume, actress

- Valentino Zeichen, poet and writer

- Laura Antonelli, film actress, active 1965 to 1991

- Sergio Endrigo, singer and songwriter

- Antonio Blasevich, soccer player

- Silvio Ballarin, scientist

- Dino Ciani, pianist

- Giovanni Cucelli, tennis player

- Renzo de' Vidovich, politician and journalist

- Aldo Duro, lexicographer

- Wilma Goich, singer

- Irma Gramatica, actress

- Ezio Loik, soccer player

- Ottavio Missoni, stylist

- Anna Maria Mori, writer

- Abdon Pamich, walker

- Pier Antonio Quarantotti Gambini, writer

- Nicolò Rode, sailor

- Orlando Sirola, tennis player

- Agostino Straulino, sailor

- Leo Valiani, politician

- Rodolfo Volk, soccer player

Legacy

Property reparation

On 18 February 1983 Yugoslavia and Italy signed a treaty in Rome where Yugoslavia agreed to pay US$110 million for the compensation of the exiles' property which was confiscated after the war in the Zone B of Free Territory of Trieste.[90][91]

However, the issue of the property reparation is enormously complex and remains unresolved: as of 2022, the exiles have not yet received compensation. Indeed, there is very little probability that exiles out of the Zone B of the Free Territory of Trieste will ever be compensated. The matter of property compensation is included in the program of the Istrian Democratic Assembly, the regional party currently administrating the Istria County.

Minority rights in Yugoslavia

In connection with exodus and during the period of communist Yugoslavia (1945–1991), the equality of ethno-nations and national minorities and how to handle inter-ethnic relations was one of the key questions of Yugoslav internal politics. In November 1943, the federation of Yugoslavia was proclaimed by the second assembly of the Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ). The fourth paragraph of the proclamation stated that "Ethnic minorities in Yugoslavia shall be granted all national rights". These principles were codified in the 1946 and 1963 constitutions and reaffirmed again, in great detail, by the last federal constitution of 1974.[92]

It declared that the nations and nationalities should have equal rights (Article 245). It further stated that "… each nationality has the sovereign right freely to use its own language and script, to foster its own culture, to set up organizations for this purpose, and to enjoy other constitutionally guaranteed rights…" (Article 274).[93]

Day of Remembrance

In Italy, Law 92 of 30 March 2004[94] declared February 10 as a Day of Remembrance dedicated to the memory of the victims of Foibe and the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus. The same law created a special medal to be awarded to relatives of the victims:

Medal of Day of Remembrance to relatives of victims of foibe killings

Medal of Day of Remembrance to relatives of victims of foibe killings

Historical debate

There is not yet complete agreement amongst historians about the causes and the events triggering the Istrian exodus. According to the historian Pertti Ahonen:[95]

Motivations behind the emigration are complex. Fear caused by the initial post-war violence (summary killings, confiscations, pressure from the governmental authorities) was a factor. On the Yugoslav side, it does not appear that an official decision for expulsion of Italians in Yugoslavia was ever taken. The actions of the Yugoslav authorities were contradictory: on the one hand, there were efforts to stem the flow of emigrants, such as placement of bureaucratic hurdles for emigration and suppression of its local proponents. On the other hand, Italians were pressured to leave quickly and en masse.

Slovenian historian Darko Darovec[96] writes:

It is clear, however, that at the peace conferences the new State borders were not being drawn using ideological criteria, but on the basis of national considerations. The ideological criteria were then used to convince the national minorities to line up with one or the other side. To this end socio-political organisations with high-sounding names were created, The most important of them being SIAU, the Slavic-Italian Anti-Fascist Union, which by the necessities of the political struggle mobilised the masses in the name of 'democracy'. Anyone who thought differently, or was nationally 'inconsistent', would be subjected to the so-called 'commissions of purification'. The first great success of such a policy in the national field was the massive exodus from Pula, following the coming into effect of the peace treaty with Italy (15 September 1947). Great ideological pressure was exerted also at the time of the clash with the Kominform which caused the emigration of numerous sympathisers of the CP, Italians and others, from Istra and from Zone B of the FTT (Free Territory of Trieste)

For the mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission:[97]

Since the first post-war days, some local activists, who wreaked their anger over the acts of the Istrian Fascists upon the Italian population, had made their intention clear to rid themselves of the Italians who revolted against the new authorities. However, expert findings to-date do not confirm the testimonies of some – although influential – Yugoslav personalities about the intentional expulsion of Italians. Such a plan can be deduced – on the basis of the conduct of the Yugoslav leadership – only after the break with the Informbiro in 1948, when the great majority of the Italian Communists in Zone B – despite the initial cooperation with the Yugoslav authorities, against which more and more reservations were expressed – declared themselves against Tito's Party. Therefore, the people's government abandoned the political orientation towards the "brotherhood of the Slavs and Italians", which within the framework of the Yugoslav socialist state allowed for the existence of the politically and socially purified Italian population that would respect the ideological orientation and the national policy of the regime. The Yugoslav side perceived the departure of Italians from their native land with growing satisfaction, and in its relation to the Italian national community the wavering in the negotiations on the fate of the FTT was more and more clearly reflected. Violence, which flared up again after the 1950 elections and the 1953 Trieste crisis, and the forceful expulsion of unwanted persons were accompanied by measures to close the borders between the two zones. The national composition of Zone B was also altered by the immigration of Yugoslavs to the previously more or less exclusively Italian cities.

The remaining Italians

According to the census organized in Croatia in 2001 and that organized in Slovenia in 2002, the Italians who remained in the former Yugoslavia amounted to 21,894 people (2,258 in Slovenia and 19,636 in Croatia).[6][7] The number of speakers of Italian is larger if taking into account non-Italians who speak it as a second language.

In addition, since the dissolution of Yugoslavia, a significant portion of the population of Istria opted for a regional declaration in the census instead of a national one. As such, more people have Italian as a first language than those having declared Italian.

The number of people resident in Croatia declaring themselves Italian almost doubled between 1981 and 1991 censuses (i.e. before and after the dissolution of Yugoslavia).[98] The daily newspaper La Voce del Popolo, the main newspaper for Italians of Croatia, is published in Rijeka/Fiume.

Official bilingualism

_bilingual.jpg.webp)

Italian is co-official with Slovene in four municipalities in the Slovenian portion of Istria: Piran (Italian: Pirano), Koper (Italian: Capodistria), Izola (Italian: Isola d'Istria) and Ankaran (Italian: Ancarano). In many municipalities in the Croatian portion of Istria there are bilingual statutes, and the Italian language is considered to be a co-official language. The proposal to raise Italian to a co-official language, as in the Croatian portion of Istria, has been under discussion for years.

By recognizing and respecting its cultural and historical legacy, the City of Rijeka ensures the use of its language and writing to the Italian indigenous national minority in public affairs relating to the sphere of self-government of the City of Rijeka. The City of Fiume, within the scope of its possibilities, ensures and supports the educational and cultural activity of the members of the indigenous Italian minority and its institutions.[99]

In various municipalities of Croatian Istria, census data shows that significant numbers of Italians still live in Istria, such as 51% of the population of Grožnjan/Grisignana, 37% at Brtonigla/Verteneglio, and nearly 30% in Buje/Buie.[100] In the village there, it is an important section of the "Comunità degli Italiani" in Croatia.[101] Italian is co-official with Croatian in nineteen municipalities in the Croatian portion of Istria: Buje (Italian: Buie), Novigrad (Italian: Cittanova), Izola (Italian: Isola d'Istria), Vodnjan (Italian: Dignano), Poreč (Italian: Parenzo), Pula (Italian: Pola), Rovinj (Italian: Rovigno), Umag (Italian: Umago), Bale (Italian: Valle d'Istria), Brtonigla (Italian: Verteneglio), Fažana (Italian: Fasana), Grožnjan (Italian: Grisignana), Kaštelir-Labinci (Italian: Castellier-Santa Domenica), Ližnjan (Italian: Lisignano), Motovun (Italian: Montona), Oprtalj (Italian: Portole), Višnjan (Italian: Visignano), Vižinada (Italian: Visinada) and Vrsar (Italian: Orsera).[102]

Education and Italian language

Slovenia

Beside Slovene language schools, there are also kindergartens, primary schools, lower secondary schools and upper secondary schools with Italian as the language of instruction in Koper/Capodistria, Izola/Isola and Piran/Pirano. At the state-owned University of Primorska, however, which is also established in the bilingual area, Slovene is the only language of instruction (although the official name of the university includes the Italian version, too).

Croatia

Beside Croat language schools, in Istria there are also kindergartens in Buje/Buie, Brtonigla/Verteneglio, Novigrad/Cittanova, Umag/Umago, Poreč/Parenzo, Vrsar/Orsera, Rovinj/Rovigno, Bale/Valle, Vodnjan/Dignano, Pula/Pola and Labin/Albona, as well as primary schools in Buje/Buie, Brtonigla/Verteneglio, Novigrad/Cittanova, Umag/Umago, Poreč/Parenzo, Vodnjan/Dignano, Rovinj/Rovigno, Bale/Valle and Pula/Pola, as well as lower secondary schools and upper secondary schools in Buje/Buie, Rovinj/Rovigno and Pula/Pola, all with Italian as the language of instruction.

The city of Rijeka/Fiume in the Kvarner/Carnaro region has Italian kindergartens and elementary schools, and there is an Italian Secondary School in Rijeka.[103] The town of Mali Lošinj/Lussinpiccolo in the Kvarner/Carnaro region has an Italian kindergarten.

In Zadar, in Dalmatia/Dalmazia region, the local Community of Italians has requested the creation of an Italian asylum since 2009. After considerable government opposition,[104][105] with the imposition of a national filter that imposed the obligation to possess Italian citizenship for registration, in the end in 2013 it was opened hosting the first 25 children.[106] This kindergarten is the first Italian educational institution opened in Dalmatia after the closure of the last Italian school, which operated there until 1953.

Since 2017, a Croatian primary school has been offering the study of the Italian language as a foreign language. Italian courses have also been activated in a secondary school and at the faculty of literature and philosophy.[107]

See also

- Foibe massacres

- National Memorial Day of the Exiles and Foibe

- Free Territory of Trieste

- World War II in Yugoslavia

- Italian Social Republic

- Istria

- Italian language in Croatia

- Italian language in Slovenia

- Dalmatia

- Italianization

- Croatisation

- Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–50)

- Ethnic cleansing in the Bosnian War

- Niçard exodus

References

- 1 2 "Il Giorno del Ricordo" (in Italian). Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- 1 2 "L'esodo giuliano-dalmata e quegli italiani in fuga che nacquero due volte" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ↑ Tobagi, Benedetta. "La Repubblica italiana | Treccani, il portale del sapere". Treccani.it. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ Thammy Evans & Rudolf Abraham (2013). Istria. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 11. ISBN 9781841624457.

- 1 2 James M. Markham (6 June 1987). "Election Opens Old Wounds in Trieste". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Državni Zavod za Statistiku" (in Croatian). Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- 1 2 "Popis 2002". Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ota Konrád; Boris Barth; Jaromír Mrňka, eds. (2021). Collective Identities and Post-War Violence in Europe, 1944–48. Springer International Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 9783030783860.

- 1 2 Bloxham, Donald; Dirk Moses, Anthony (2011). "Genocide and ethnic cleansing". In Bloxham, Donald; Gerwarth, Robert (eds.). Political Violence in Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 125. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511793271.004. ISBN 9781107005037.

- 1 2 Pamela Ballinger (7 April 2009). Genocide: Truth, Memory, and Representation. Duke University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0822392361. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- 1 2 Tesser, L. (14 May 2013). Ethnic Cleansing and the European Union – Page 136, Lynn Tesser. Springer. ISBN 9781137308771.

- ↑ Ballinger, Pamela (2003). History in Exile: Memory and Identity at the Borders of the Balkans. Princeton University Press. p. 103. ISBN 0691086974.

- ↑ Anna C. Bramwell, University of Oxford, UK (1988). Refugees in the Age of Total War. Unwin Hyman. pp. 139, 143. ISBN 9780044451945.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Jaka Bartolj. "The Olive Grove Revolution". Transdiffusion. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010.

While most of the population in the towns, especially those on or near the coast, was Italian, Istria's interior was overwhelmingly Slavic – mostly Croatian, but with a sizeable Slovenian area as well.

- 1 2 "Istrian Spring". Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- 1 2 . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 886–887.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 Bartoli, Matteo (1919). Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia (in Italian). Tipografia italo-orientale. p. 16.[ISBN unspecified]

- 1 2 Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967). Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, 1870–1925. Methuen. p. 107. ISBN 9780416189407.

- ↑ VIII. Censimento della popolazione 21. aprile 1936. Vol II, Fasc. 24: Provincia del Friuli; Fasc. 31: Provincia del Carnero; Fasc. 32: Provincia di Gorizia, Fasc. 22: Provincia dell'Istria, Fasc. 34: Provincia di Trieste; Fasc. 35: Provincia di Zara, Rome 1936. Cited at "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 Matjaž Klemenčič, The Effects of the Dissolution of Yugoslavia on Minority Rights: the Italian Minority in Post-Yugoslav Slovenia and Croatia. See "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "A est: Istria" (in Italian). 5 May 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ↑ Alvise Zorzi, La Repubblica del Leone. Storia di Venezia, Milano, Bompiani, 2001, ISBN 978-88-452-9136-4., pp. 53-55 (in italian)

- 1 2 Sethre, Janet (2003). The Souls of Venice. McFarland. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-7864-1573-8.

- 1 2 "Historic overview-more details". Istra-Istria.hr. Istria County. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ↑ John Mason Neale, Notes Ecclesiological & Picturesque on Dalmatia, Croatia, Istria, Styria, with a visit to Montenegro, pg. 76, J.T. Hayes - London (1861)

- ↑ "Dalmatia history". Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Region of Istria: Historic overview-more details". Istra-istria.hr. Archived from the original on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Italian islands in a Slavic sea". Arrigo Petacco, Konrad Eisenbichler, A tragedy revealed, p. 9.

- ↑ Prominent Istrians

- ↑ ""L'Adriatico orientale e la sterile ricerca delle nazionalità delle persone" di Kristijan Knez; La Voce del Popolo (quotidiano di Fiume) del 2/10/2002" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ "L'ottocento austriaco" (in Italian). 7 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ↑ "Trieste, Istria, Fiume e Dalmazia: una terra contesa" (in Italian). Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- 1 2 Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971

- ↑ Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971, vol. 2, p. 297. Citazione completa della fonte e traduzione in Luciano Monzali, Italiani di Dalmazia. Dal Risorgimento alla Grande Guerra, Le Lettere, Firenze 2004, p. 69.)

- ↑ Jürgen Baurmann, Hartmut Gunther and Ulrich Knoop (1993). Homo scribens : Perspektiven der Schriftlichkeitsforschung (in German). Walter de Gruyter. p. 279. ISBN 3484311347.

- ↑ "Dalmazia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. III, Treccani, 1970, p. 729

- ↑ Peričić, Šime (19 September 2003). "O broju Talijana/talijanaša u Dalmaciji XIX. stoljeća". Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru (in Croatian) (45): 342. ISSN 1330-0474.

- ↑ "Spezialortsrepertorium der österreichischen Länder I-XII, Wien, 1915–1919". Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ "Spezialortsrepertorium der österreichischen Länder I-XII, Wien, 1915–1919". Archived from the original on 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Dalmazia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. III, Treccani, 1970, p. 730

- ↑ "First World War.com – Primary Documents – Italian Entry into the War, 23 May 1915". Firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- 1 2 "First World War.com – Primary Documents – Treaty of London, 26 April 1915". Firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Lo Stato libero di Fiume:un convegno ne rievoca la vicenda" (in Italian). 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Dossier: Islam in Europe, European Islam". Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ "Contro Operazione Foibe" di Giorgio Rustia

- ↑ "Trieste, quando erano gli italiani a fare pulizia etnica" (in Italian). 10 February 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ A Historical Outline Of Istria Archived 11 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, razor.arnes.si. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ "Italiani di Dalmazia: 1919-1924" di Luciano Monzali

- ↑ "Il primo esodo dei Dalmati: 1870, 1880 e 1920 - Secolo Trentino". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ↑ "Partenze da Zara" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ "Map (JPG format)". Ibiblio.org. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Annessioni italiane (1941)" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ "Partisans: War in the Balkans 1941–45". Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ Italian historian Raoul Pupo's article pertinent exodus or forced migration, lefoibe.it. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ↑ "Che cosa furono i massacri delle foibe" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- 1 2 Guido Rumici (2002). Infoibati (1943-1945) (in Italian). Ugo Mursia Editore. ISBN 9788842529996.

- 1 2 "Relazione della Commissione storico-culturale italo-slovena - V Periodo 1941-1945". Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ↑ Il tempo e la storia: Le Foibe, Rai tv, Raoul Pupo

- ↑ Lowe, Keith (2012). Savage continent. London. ISBN 9780241962220.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Silvia Ferreto Clementi. "La pulizia etnica e il manuale Cubrilovic" (in Italian). Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ «....Già nello scatenarsi della prima ondata di cieca violenza in quelle terre, nell'autunno del 1943, si intrecciarono giustizialismo sommario e tumultuoso, parossismo nazionalista, rivalse sociali e un disegno di sradicamento della presenza italiana da quella che era, e cessò di essere, la Venezia Giulia. Vi fu dunque un moto di odio e di furia sanguinaria, e un disegno annessionistico slavo, che prevalse innanzitutto nel Trattato di pace del 1947, e che assunse i sinistri contorni di una "pulizia etnica". Quel che si può dire di certo è che si consumò - nel modo più evidente con la disumana ferocia delle foibe - una delle barbarie del secolo scorso.» from the official website of The Presidency of the Italian Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, official speech for the celebration of "Giorno del Ricordo" Quirinal, Rome, 10 February 2007.

- ↑ "Il giorno del Ricordo - Croce Rossa Italiana" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ↑ Società di Studi Fiumani-Roma, Hrvatski Institut za Povijest-Zagreb Le vittime di nazionalità italiana a Fiume e dintorni (1939-1947) Archived October 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali - Direzione Generale per gli Archivi, Roma 2002. ISBN 88-7125-239-X, p. 597.

- ↑ "Le foibe e il confine orientale" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ "Foibe, oggi è il Giorno del Ricordo: cos'è e perché si chiama così". La Repubblica (in Italian). GEDI Gruppo Editoriale. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

La ricorrenza istituita nel 2004 nell'anniversario dei trattati di Parigi, che assegnavano l'Istria alla Jugoslavia. Si ricordano gli italiani vittime dei massacri messi in atto dai partigiani e dai Servizi jugoslavi.

[The anniversary [was] established in 2004 on the anniversary of the Paris treaties, which assigned Istria to Yugoslavia. We remember the Italians victims of the massacres carried out by the partisans and the Yugoslav services.] - ↑ Hedges, Chris (20 April 1997). "In Trieste, Investigation of Brutal Era Is Blocked". The New York Times. Section 1, Page 6. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ↑ Micol Sarfatti (11 February 2013). "Perché quasi nessuno ricorda le foibe?". huffingtonpost.it (in Italian).

- ↑ Boscarol, Francesco (10 February 2019). "'Foibe, fascisti e comunisti: vi spiego il Giorno del ricordo': parla lo storico Raoul Pupo [Interviste]". TPI The Post Internazionale (in Italian). Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- 1 2 Pupo, Raoul (April 1996). "Le foibe giuliane 1943-45". L'Impegno, A. XVI, N. 1 (in Italian). Istituto per la storia della Resistenza e della società contemporanea nel Biellese, nel Vercellese e in Valsesia. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Georg G. Iggers (2007). Franz L. Fillafer; Georg G. Iggers; Q. Edward Wang (eds.). The Many Faces of Clio: cross-cultural Approaches to Historiography, Essays in Honor of Georg G. Iggers. Berghahn Books. p. 430. ISBN 9781845452704.

- ↑ Ballinger, Pamela (17 November 2002). History in Exile: Memory and Identity at the Borders of the Balkans. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691086972. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ Jutta Weldes.Weldes, Jutta (1999). Cultures of Insecurity: States, Communities, and the Production of Danger. U of Minnesota Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780816633081.

- ↑ Christian Jennings.Jennings, Christian (18 May 2017). Flashpoint Trieste: The First Battle of the Cold War. Bloomsbury. p. 241. ISBN 9781472821713.

- ↑ Pertti Ahonen et al.People on the move: forced population movements in Europe after World War II and its aftermath. Berg (USA). 2008. p. 107. ISBN 9781845208240.

- ↑ Jakovljević, Ilija (2009). "Biskup Nežić i osnivanje metropolije". Riječki teološki časopis. 17 (2): 344.

- 1 2 Trogrlić, Stipan (2014). "Progoni i stradanja Katoličke crkve na području današnje porečke i pulske biskupije 1945–1947" (PDF). Riječki teološki časopis (in Croatian). 22 (1): 12–18. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ↑ Medved, Marko (2009). "Župe riječke biskupije tijekom talijanske uprave". Riječki teološki časopis. 17 (2): 134.

- ↑ "Il problema del confine orientale italiano nel novecento" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- 1 2 Begonja 2005, p. 72.

- ↑ Grant, John P.; J. Craig Barker, eds. (2006). International Criminal Law Deskbook. Routledge: Cavendish Publishing. p. 130. ISBN 9781859419793.

- ↑ Pamela Ballinger (2003). History in Exile: Memory and Identity at the Borders of the Balkans. Princeton University Press (UK). p. 77. ISBN 0691086974.

- ↑ Literary and Social Diasporas: An Italian Australian Perspective. G. Rando and Gerry Turcotte. 2007. p. 174. ISBN 9789052013831. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Pamela Ballinger (2003). History in Exile: Memory and Identity at the Borders of the Balkans. Princeton University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0691086974. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Joseph B. Schechtman (1964). The refugees in the world: displacement and integration. New York, Barnes. p. 68.

- ↑ "Il TLT e il Trattato di Osimo" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ Anna C. Bramwell (1988). Refugees in the Age of Total War. University of Oxford. p. 104. ISBN 9780044451945.

- ↑ "Article in Italian (scroll down for Benvenuti)". Digilander.libero.it. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

Mi hanno cacciato dal mio paese quando avevo tredici anni. Si chiamava Isola d'Istria, Oggi è una cittadina della Slovenia (I was expelled from my country when I was thirteen. It was called Isola d'Istria, today is a town in Slovenia)

- ↑ "1975/2005 Trattato di Osimo". Trattatodiosimo.it. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ La situazione giuridica dei beni abbandonati in Croazia e in Slovenia, Leganazionale.it. Retrieved 30 December 2015.(in Italian)

- ↑ The Constitution of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, Belgrade 1946; The Constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Belgrade 1963 (cited here Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine).

- ↑ The Constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Belgrade 1989 cited here Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ http://www.camera.it/parlam/leggi/04092l.htm Archived 9 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Legge n. 92 del 30 marzo 2004

- ↑ Pertti Ahonen; et al. (2008). People on the move: forced population movements in Europe after World War II and its aftermath. Berg, USA. p. 108. ISBN 9781845208240.

- ↑ Darko Darovec. "THE PERIOD OF TOTALITARIAN RÉGIMES-The Reasons for the Exodus". www2.arnes.si. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ "PERIOD 1945–1956". Kozina.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Government use of the Italian language in Rijeka

- ↑ "SAS Output". dzs.hr. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ↑ "Comunità Nazionale Italiana, Unione Italiana". www.unione-italiana.hr. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ "LA LINGUA ITALIANA E LE SCUOLE ITALIANE NEL TERRITORIO ISTRIANO" (in Italian). p. 161. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ↑ "Byron: the first language school in Istria". www.byronlang.net. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ Reazioni scandalizzate per il rifiuto governativo croato ad autorizzare un asilo italiano a Zara

- ↑ Zara: ok all'apertura dell'asilo italiano

- ↑ Aperto “Pinocchio”, primo asilo italiano nella città di Zara

- ↑ "L'italiano con modello C a breve in una scuola di Zara". Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

Bibliography

- Begonja, Zlatko (July 2005). "Iza obzorja pobjede, Sudski procesi "narodnim neprijateljima" u Zadru 1944.-1946" [Beyond horizon of victory, Trials of "enemies of the people" in Zadar 1944-1946]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Croatian Institute of History. 37 (1): 71–82. ISSN 0590-9597.

- A Brief History of Istria by Darko Darovec

- Raoul Pupo, Il lungo esodo. Istria: le persecuzioni, le foibe, l'esilio, Rizzoli, 2005. ISBN 88-17-00562-2.

- Raoul Pupo and Roberto Spazzali, Foibe, Mondadori, 2003. ISBN 88-424-9015-6.

- Guido Rumici, Infoibati, Mursia, Milano, 2002. ISBN 88-425-2999-0.

- Arrigo Petacco, L'esodo. La tragedia negata degli italiani d'Istria, Dalmazia e Venezia Giulia, Mondadori, Milano, 1999. English translation.

- Marco Girardo, Sopravvissuti e dimenticati: il dramma delle foibe e l'esodo dei giuliano-dalmati. Paoline, 2006.

Further reading

- Pamela Ballinger, "The Politics of the Past: Redefining Insecurity along the 'World's Most Open Border'"

- Matjaž Klemenčič, "The Effects of the Dissolution of Yugoslavia on Minority Rights: the Italian Minority in Post-Yugoslav Slovenia and Croatia"

- (in Italian) Site of an association of Italian exiles from Istria and Dalmatia

- Slovene-Italian Relations 1880–1956 Report 2000 Archived 8 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Italian) Relazioni Italo-Slovene 1880–1956 Relazione 2000 Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Slovene) Slovensko-italijanski odnosi 1880–1956 Poročilo 2000 Archived 18 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Italians mark war massacre

- Monzali, Luciano (2016). "A Difficult and Silent Return: Italian Exiles from Dalmatia and Yugoslav Zadar/Zara after the Second World War". Balcanica (47): 317–328. doi:10.2298/BALC1647317M. hdl:11586/186368.