Beginning in the early days of silent films Itinerant filmmakers traveled across the US to make their movies on location with "home talent." They capitalized on the public's desire to see themselves and/or their children in the movies. The filmmakers hoped to cash in on the vanity of politicians, high-society types and prominent businessmen and their families. They would pay a small fee to be in the movie and townspeople would pay to watch their neighbors in the film. It was also common for the local chamber of commerce to pay the production expenses and choose the backdrop and locations for filming. Many times it was promised that the film would be shown around the country, enticing the viewers to come and visit the places they saw. The film would then be returned to the Chamber after its run. They often filmed the same characters in the same story over and over, only changing the cast in each city. Sometimes the title would change leading people to think their particular film was unique. These itinerant films were popular in the silent era, but in some cases they were still operating into the 1970s. Several people made careers out of making itinerant films.[1]

Practitioners

O.W. Lamb was an early entrant into the field of itinerant filmmaking. His company was Paragon Feature Films and it was very active between 1914 and 1916. He was responsible for The Lumberjack (1914), the first movie to be made in Wisconsin and Present and Past in the Cradle of Dixie (1914) made in Montgomery, Alabama. Lamb also made The Blissveldt Romance (1915) in Grand Rapids, Michigan and The Spirit of Columbus 1865-1915 (1915) in Columbus, Georgia. The Maid of the Miami (1915) was made in Dayton, Ohio. Lamb worked with the Chamber of Commerce who often sponsored the production. One hallmark of Lamb's operation would be to offer a reward of a five-dollar gold piece to the person who came up with title for the film.[2]

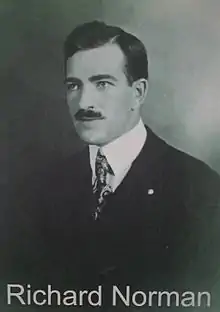

Richard Norman made a film entitled The Wrecker over 40 times in various cities in the Midwest and South between 1915 and 1919. Norman had purchased footage of a train collision that was used as the climax to the story. Unfortunately, no copies exist of this film. He established Norman Studios in Jacksonville, Florida in 1919 and found success making "race films." His first was an all-black version of The Wrecker called The Green-eyed Monster (1919). His film The Flying Ace (1926) is the only one of his movies known to have survived.

Don O. Newland was active in the 1920s and 1930s. His claims of working with Mack Sennett and Mary Pickford are not backed up by his Internet Movie Database biography. He made many of his films in Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Ohio. He used the name of the town followed by "Hero" for the titles to his films. Known titles include Janesville's Hero (1926), Belvidere's Hero (1926), Tyrone's Hero (1934) and Huntingdon's Hero (1934). The opening credits are available to watch for Tyrone's Hero and the entire film is available for Belvidere's Hero.

Melton Barker was active later than most. His Kidnapper's Foil was filmed dozens of times between the 1930s and 1970s, making him possibly the last of his kind and even attempted to move into television. He specialized in using children in his films, hence the name of his company, Melton Barker Juvenile Productions. Kidnapper's Foil was named to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 2012.[3]

References

- ↑ "MeltonBarker.org". Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ↑ Bellware, Daniel (Spring 2016), "Movie Makers Come to Columbus'" Muscogiana, Columbus, Georgia: Muscogee Genealogical Society, p. 2.

- ↑ "New York Times". Retrieved March 22, 2017.