Järntorget (Swedish for 'The Iron Square') is a small public square in Gamla stan, the old town in central Stockholm, Sweden. Located in the southernmost corner of the old town, the square connects the thoroughfares Västerlånggatan and Österlånggatan, while the two alleys, Södra Bankogränd and Norra Bankogränd, stretches east to connect the square to Skeppsbron, and two other alleys, Järntorgsgatan and Triewaldsgränd, leads south to Slussplan and Kornhamnstorg respectively.

The second oldest square in Stockholm, slightly younger than Stortorget, Järntorget dates back to around 1300 and remained the city's most important trade centre for centuries — constantly busy and crowded, scents and noise intermixing while goods were transported from shore to shore across the square and up and down the attics of the surrounding buildings.[1]

History

Prehistory

The island is part of the post glacial boulder ridge Brunkebergsåsen stretching north to south through central Stockholm forming an elongated hill on Norrmalm while narrowing and levelling off to a low edge just north of Järntorget. The ridge is penetrated by the two outflows of Lake Mälaren, of which the southern once formed the southern extent of the square, the shoreline passing over today's square through the bank building on the eastern side. The edges of the central plateau of the old town originally consisted of steep slopes, today disintegrated by excavations and concealed by the urban throng on the island. The block Trivia north of the square still veil the edge of the boulder ridge, during the Middle Ages six metres tall and hidden by a terraced city wall. The square gradually developed from a simple transshipment area on the cape south of the ridge to a medieval market place flanked by two landing bridges, Kornhamn ("Grain Harbour") by Lake Mälaren and Kogghamn ("Merchant Ship's Harbour") facing the Baltic Sea.[2]

Middle Ages

Originally called Korntorget ("Grain Square"), the square is first mentioned as Järntorget in 1489, both names being used in parallel until 1513 when iron trade had surpassed barley trade in importance. Controlling and putting a charge on the trade meant an important source of income for both the city and the king, and at least from the mid 14th century the city's official scales were located by the southern square on Number 84.[2] Except iron, Sweden exported copper, silver, hide, fur, train oil, salmon, and butter, while importing salt, broadcloth, beer, wine, and luxury items such as spice, glass, and ceramics. During the Middle Ages, the surrounding area was dominated by German merchants, a situation over the century balanced by people from the British Isles, France, and the Netherlands.[1] In medieval times, the square was considerably larger than today. The blocks on the eastern side were aligned to a discontinued alley passing through the blocks south-east of the square (on the left side of Järntorgsgatan), and the square thus encompassed at least half of the present area today occupied by these blocks. In the 16th century sheds were constructed along the eastern side of the square.[2]

Great Power Era

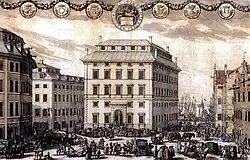

In the early 17th century, numerous taverns were located around the square, the signs of which being referred to as The Blue Eagle, The Lion, The Griffin, Three Crowns, The Moon, The Sun, The Star, and The Scales.[1] The city's official scales were relocated to Södermalm in 1662 and the entire area around the square underwent a transformation as wealthy people had taller and more prestigious buildings erected over merged lots. The development was actively supported by the king who wanted the capital to be more representative, the medieval buildings thus disappearing together with medieval alleys. The development was further promoted by the construction of Södra Bankohuset, the national bank building on number 84 in 1680. The building, originally designed by Nicodemus Tessin the Elder, was subsequently enlarged eastward to the design of other architects, and the lot north of it was purchased for the construction of the northern bank building, Norra Bankohuset. The building remained the headquarters of the Bank of Sweden until the early 20th century.[2]

Modern history

During the 18th and 19th century, the square was used as a greengrocer's market place and the buildings around it became known as distinguished addresses. Sundbergs konditori, the oldest confectioner's shop in town, on Number 83, was founded in 1785. [1]

A walk around the square

The numbers of the buildings surrounding the square are continuous with those on Västerlånggatan, and are therefore listed here counter clockwise from the southern end of Västerlånggatan:

Through the four-storey building on Number 78 (Deucalion 2) a medieval alley once passed from Västerlånggatan to Kornhamnstorg and the building facing the square was thus a very narrow block. While the present shape of the building dates back to 1791, the interior was much altered during the second half of the 19th century and the modern shop windows were added in the 20th century. Remains of the buildings located here in the 17th century are, however, still part of the modern structure, together with fractions of the interior.[3]

The Art Nouveau façade of Number 80 (Medusa 4), including the large windows and cast iron colonnettes, got much its present appearance in 1907 following a reconstruction of the shop (at the time an ironmongery), save for a minor enlargement of the shop windows in 1941, and the entrance of the Coop store added in 1981.[4] On the address was the photographic studio of David Jacoby, the numerous portraits from which still attracts the interest of many Swedish genealogists.[5]

On Number 84 (Pluto) is Södra Bankohuset, the oldest national bank building in the world. The western façade facing the square, built in 1675–1685 to the design of Nicodemus Tessin the Elder, is inspired by Italian Renaissance, the strict style meant to emphasise the motto of the bank: Hinc Robur et Securitas, "Hence Stability and Reliability". The portal is a direct quotation of Vignola's portal at Villa Farnese in Caprarola. The original design was repeated around the building by later architects.[6]

In front of the bank building is one of the famous sights at Järntorget, the statue of Evert Taube (1890–1976); the popular troubadour and composer in beret and sun-glasses, with music sheets in his hands. The sculpture was inaugurated in 1985 and the artist Karl-Göte Bejemark (1922–2000), who also made other popular sculptures depicting famous Swedes such as Greta Garbo and Nils Ferlin, chose natural colours for the sculpture and placed it directly on the pavement to give the impression the troubadour is on his way to his favourite hangout, Den Gyldene Freden just a block away.[7]

Atop the old-fashion, plain white façade of Number 85 (Trivia 3) is a crane still reminding of the trade once dominating the square. Passing through Number 83 (Trivia 2) was during the 15th and 16th centuries a passage by the end of the later century called Spilaregången, after the workers called Spilare who used to pack iron, fish, and other goods in casks there.[2]

The well centred on the square is made of cast iron, modelled to a British prototype, and was a donation from the National Bank in 1829.[1]

See also

Gallery

Old crane on Number 85.

Old crane on Number 85. Fissured façade of Number 78.

Fissured façade of Number 78. Detail of the portal of Number 84.

Detail of the portal of Number 84. Statue of Evert Taube in front of the old bank building.

Statue of Evert Taube in front of the old bank building. Façade of Number 85 viewed from Norra Bankogränd.

Façade of Number 85 viewed from Norra Bankogränd.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Béatrice Glase, Gösta Glase (1988). "Västra Stadsholmen". Gamla stan med Slottet och Riddarholmen (in Swedish) (3rd ed.). Stockholm: Bokförlaget Trevi. pp. 76–78. ISBN 91-7160-823-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marianne Aaro (2005-04-05). "Vågen och banken i kvarteret Pluto" (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Statens Fastighetsverk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ Tord O:son Nordberg (1975). "Deucalion". Gamla stan i Stockholm I - Kvarteren Achilles—Glaucus (in Swedish). Stockholm: Stockholms Kommunalförvaltning. pp. 237, 238, 241–242.

- ↑ Maria Lorentzi (2002–2003). "Butiksfasader i Gamla stan. Inventering" (PDF). Stockholm City Museum. pp. 606–611. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ↑ "Porträttfynd: David Jacoby, Järntorget 80, Stockholm" (in Swedish). Nättidningen Rötter. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

- ↑ "Södra innerstaden". Guide till Stockholms arkitektur (2nd ed.). Stockholm: Arkitektur Förlag AB. 1999. p. 123. ISBN 91-86050-41-9.

- ↑ "Konsten i Gamla stan" (in Swedish). City of Stockholm. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

External links

Media related to Järntorget, Stockholm at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Järntorget, Stockholm at Wikimedia Commons- hitta.se - Location map and virtual walk.