James Rufus Bratton | |

|---|---|

| Born | November 12, 1821 |

| Died | September 2, 1897 (aged 75) York County, South Carolina, US |

| Other names | John Simpson |

| Occupation | Medical doctor |

| Organization | Ku Klux Klan |

| Criminal charge | Murder |

| Details | |

| Victims | Jim Williams |

James Rufus Bratton (1821–1897) was a doctor, army surgeon, civic leader, and leader in the Ku Klux Klan in South Carolina with whom he was guilty of committing numerous crimes. Bratton trained in medicine in Philadelphia in the 1840s but spent most of his life in Yorkville, South Carolina. He joined the Confederate Army as an assistant surgeon in April 1861, the opening month of the American Civil War. After the war, he became an opponent of Reconstruction and a leader of the Ku Klux Klan. He was one of the leaders linked in the lynching and killing of local black leader Jim Williams. This led to a string of violent attacks which eventually led to a large group of York County blacks emigrating to Liberia. Bratton fled to London, Ontario, to escape prosecution, but later was able to return to South Carolina, where he pursued his career in medicine for the remainder of his life.

Early life

Bratton was born November 12, 1821, in Brattonsville, York County, South Carolina.[1] He had thirteen siblings, and his parents were John Bratton and Harriet Rainey, daughter of James Rainey. His brothers included Thomas Bratton and Napoleon Bonaparte Bratton.[2] His paternal grandparents were Martha and Colonel William Bratton, famous for his victory over Captain Huck of the British army during the American Revolution.[1] Bratton was the first cousin of Confederate General John Bratton.[3]

Bratton attended school at Mt. Zion Academy in Winnsboro, South Carolina, and attended the College of South Carolina, where he graduated in 1843. He continued his medical training and in 1845 took a full course in the hospital at the University of Pennsylvania,[1] and graduated from Jefferson Medical College in Pennsylvania.[2]

He returned to South Carolina, and in Yorkville he set up a practice with William Moore, the pair partnering for about a year before he opened his own practice in Yorkville in 1847, where he soon took another younger partner.[1] Bratton was a very talented doctor. In a famous case in the mid-1850s, he trephined a skull when the patient suffered great pressure on the brain following a kick by a horse, saving the patient.[4]

In 1850 Bratton married Rebecca Massey of Lancaster County. The pair had five sons and two daughters.[1] Bratton's house was originally built by local lawyer Robert Clendinen (1816-1830). It was razed in 1956 and the spot is, as of 2016, identified by a historic marker.[5]

Civil War

Bratton joined the Confederacy in the Civil War. On April 13, 1861, he volunteered to be an assistant surgeon for the Fifth Regiment, South Carolina Infantry Volunteers under Colonel Jenkins. He was then placed in charge of the Fourth Division of the Winder Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, where he served three years and was promoted to the rank of surgeon. He requested lighter duty and was transferred to the 20th Regiment of Virginia surgeons under General Braxton Bragg at Milledgeville, Georgia. After Union General William T. Sherman marched his army through Georgia, the hospital was dismantled and Bratton was furloughed and returned to Yorkville. On April 28 and 29 of 1865, Confederate President Jefferson Davis was fleeing Union forces and came through Yorkville, and Bratton hosted Davis and two of his aides.[1]

Post-Civil War

After the war and the emancipation of the slaves, Bratton's plantation saw lean times. Many of his former slaves left,[6] and Bratton worked the fields in 1866. In 1868, he sent away former slave "Bob and his family" on account of his radical politics. His farm was still not profitable in 1867 through 1869, while Bratton attempted to resume medical practice.[1] In 1870 he had in part recovered and incorporated the Columbia Oil Company. During this time, Bratton became active in anti-Reconstruction activities and became a leader in the York County Ku Klux Klan.[7]

Ku Klux Klan

In February 1871, local black preacher Elias Hill met with local Ku Klux Klan leaders to negotiate the safety of blacks in the community. These negotiations were not successful, and around February 12, eight black men were killed by 500 to 700 whites in black gowns with masks, and was followed by nightly Klan raids for months.[8]

An important black leader in York County of that time was a former Union soldier and local militia leader named James Rainey, also known as Jim Williams. Williams was a former slave of Bratton's brother, John S. Bratton, and his wife, Harriet J. Rainey.[7] At that time, black militias like this were known as Union Leagues. On February 11, 1871, Jim Williams, along with June Moore (nephew of Elias Hill) and a group of blacks met with a group of whites led by Bratton at a crossroads near Clay Hill to seek to deescalate tensions. Williams suggested that he would be willing to relinquish his militia weapons, and Black Union League leaders agreed to cease nighttime meetings. The truce was broken the next day when a race riot broke out involving 500 to 700 whites in neighboring Union County, killing eight blacks.[8]

Some whites claimed Williams had threatened to kill local whites and that Williams' militia was stockpiling weapons. It was also claimed that Williams claimed to desire to rape white women if he could.[7] Further, Bratton claimed that Williams and his militia were responsible for a rash of fires at white-owned properties[9] On March 6, 1871, about forty men seized Williams from his home and hung him from a tree and shot him with many bullets. Bratton was said to have placed the noose around Williams' neck. Williams was subsequently brought to Bratton's office where Bratton, in his medical capacity, served the inquest.[7]

Lynching of Jim Williams

On March 6, 1871, James Rufus Bratton led a group of about 70 white men from their muster at the Briar Patch muster ground 5 miles (8 km) west of Yorkville to the Williams cabin.[10] At that time, James William Avery and Bratton were the head and number two in the local Klan.[3]

The mob first went to the home of Union League member Andy Timons, beating Timons to learn the whereabouts of Williams' home.[9] At Williams' cabin, they found him hiding under the floorboards. They grabbed him and pulled him kicking and screaming from the house. Someone, probably Bratton, placed a noose around William's neck. Outside, they tied the rope to a tree 10 to 12 feet (3.0 to 3.7 m) off the ground and forced Williams to climb to the limb. Bob Caldwell, another Klansman, climbed to the limb and pushed Williams, who then dangled from the limb by his hands. Caldwell used a knife to hack at William's fingers until he released, whence he "died cursing, pleading and praying all in one breath."[11]: 76–78 Williams was subsequently brought to Bratton's office where Bratton, in his medical capacity, served the inquest.[7]

The mob visited several other homes of men involved in the Union League militia, succeeding in gathering 23 guns but no other members. Members of the league swore vengeance, but did not act. Companies B, E, and K of George Armstrong Custer's Seventh U.S. Cavalry led by Major Lewis Merrill arrived in the area to try to quell the violence,[11]: 1–5 Elias Hill stepped in to lead the league, now in disarray. In another raid, Hill's nephews, Solomon Hill and June Moore, were attacked and forced to renounce their Republican Party affiliation in the local paper, the Yorkville Enquirer.[8]

Elias Hill was attacked on May 5, 1871. This was the first episode of Ku Klux Klan violence Merrill saw in York County first hand, and he was unable to immediately step in to protect the black citizens of York County. Eight days after the attack, Merrill met with community leaders demanding change, although violence continued over the summer.[11] Merrill's efforts eventually led to the dismantling of much of the Klan in the county, although Bratton was never successfully prosecuted.[9]

Flight to Ontario

Shortly after these events, Bratton and Avery were placed on the federal government's most wanted list for the murder of Jim Williams.[1] Later in 1871, he fled York County to his sister's house, Sophia O'Bannon in Barnwell, South Carolina. He may have then fled to Selma, Alabama. He lived under the name of Simpson and became involved in coal mining. About the time he was purchasing a large tract for his coal business, he had to flee again, moving to Memphis, Tennessee, with his brother John, who was also a fugitive. On May 22, 1872, under the name of John Simpson, Bratton fled to the home of expatriate G. Manigault in London, Ontario. In London, he stayed at the Revere House on Richmond Street before he moved to the Sarah Hill Boarding House on Wellington Street, and was a part of a growing community of ex-Confederates in the city.[1]

South Carolina Governor Robert Kingston Scott sent Isaac Bell Cornwell to apprehend him. Cornwell applied to the United States Secret Service Department and received a warrant from President Ulysses Grant and was assisted by Joseph G. Hester of the department. They went to London and after a few days apprehended Bratton with some struggle. On the way to the train depot, Bratton convinced Cornwell to read the warrant for his arrest. It was claimed that the warrant was not for Bratton, but for James William Avery.[1]

Bratton was brought from London to Yorkville where he was jailed. He was granted a bail of about $12,000, which 13 local men raised. American newspapers and Canadian authorities called the apprehension a kidnapping, and the Canadian government called for Bratton's immediate release and return to Canada, as both the Canadian government and public were enraged at the violation of their national sovereignty. The Canadian Federal Government had the issue to the House of Commons on June 11, 1872. The House almost unanimously agreed Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada's first Prime Minister, sent formal inquiries to the British Parliament in London. This resulted in Queen Victoria herself intervening, the Canadian government would also send a complaint to the Office of the British Ambassador in Washington, D.C., claiming that America had violated international law and had ignored the proper steps needed for extradition.

The London Police Service had arrested Issac Cornwall on June 10, 1872, when he was again caught in London. he was placed in the cells at the London Police Station and the preliminary hearing was held on June 13, all who had witnessed the abduction of Bratton testified at the trial. With testimony from Bratton himself, who had been released two days before the trial began, Cornwall was sentenced to 3 years in Kingston penitentiary for his role in the kidnapping. Looking to avoid an international incident, Bratton was sent back to Ontario on June 11, where he was received warmly. Bratton continued his medical practice in London for some time, where he was highly respected for his work. In Canada, the violence of Bratton's crimes and his Ku Klux Klan connections were not noted.[12] He remained in Canada for a few years, but eventually returned to York County.

Legacy and death

Bratton was involved in freemasonry; when he died, he was a 33rd degree Mason. For some period in his life, he was president of the South Carolina State Medical Association.[13]

He died September 2, 1897. He was buried in the family burying ground at Bethesda.[14]

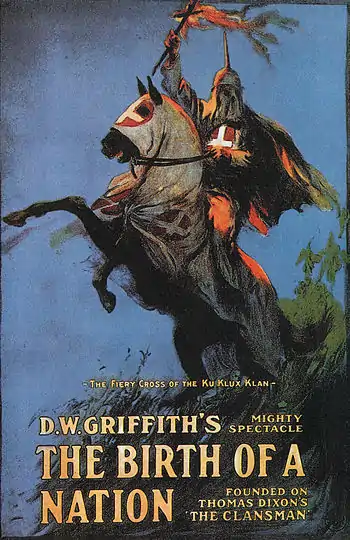

Bratton's Klan activities are said to be the inspiration for Thomas Dixon Jr.'s novel The Clansman, which was the basis of the movie The Birth of a Nation. Dixon had relatives in York County from which he may have learned about Bratton.[1]

Further reading

- Excerpts from the diary of James Rufus Bratton are available at: West, Jerry L. The Bloody South Carolina Election of 1876: Wade Hampton III, the Red Shirt Campaign for Governor and the End of Reconstruction. McFarland (2010), p. 189

- Bratton family papers

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 West, Jerry Lee. The Reconstruction Ku Klux Klan in York County, South Carolina, 1865-1877. McFarland (2002), p. 126-130

- 1 2 Evans, Clement Anselm. Capers, Ellison; South Carolina, Confederate Publishing Company, 1899

- 1 2 Weiner, Mark S. Black Trials: Citizenship from the Beginnings of Slavery to the End of Caste. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group (2007), p. 201

- ↑ Tall Tales of York County: Ghostly Secrets, Daredevil Priests and Walking on Water, The History Press, 2006, p. 66.

- ↑ Scott, Brian. History Happened Here: South Carolina's Roadside Historical Markers, lulu.com, p. 591

- ↑ He noted in Lancaster that Allston, Fred and his wife, and Bill were all slaves that left. Hannah and Heyward left, but came back in 1869. West, Jerry Lee. The Reconstruction Ku Klux Klan in York County, South Carolina, 1865-1877. McFarland (2002), p. 127

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gillin, Kate Côté. Shrill Hurrahs: Women, Gender, and Racial Violence in South Carolina, 1865-1900. Univ of South Carolina Press (2013)

- 1 2 3 Witt, John Fabian. Patriots and Cosmopolitans: Hidden Histories of American Law. Harvard University Press (2009), p.85-86, 128-149

- 1 2 3 Pearl, Matthew. "K Troop", Slate.com, March 4, 2016. http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/history/2016/03/how_a_detachment_of_u_s_army_soldiers_smoked_out_the_original_ku_klux_klan.html

- ↑ Other Klan members involved included Chambers Brown; Sylvanus, William, James, and Hugh Shearer; Robert Riggins; Hugh Kell; Henry Warlock; Napoleon Miller; Alonzo Brown; William Johnson; James Neal; Addison and Miles Carrol; Harvey Gunning; Robert and John Caldwell; Rucus McLean; Bascom Kennedy; Holbrook Good; Richard Bigham; Eli Ross Stewart; Samuel Ferguson; and Joe Martin. Weiner, Mark S. Black Trials: Citizenship from the Beginnings of Slavery to the End of Caste. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group (2007), p. 201

- 1 2 3 Martinez, James Michael. Carpetbaggers, Cavalry, and the Ku Klux Klan: Exposing the Invisible Empire During Reconstruction. Rowman & Littlefield (2007)

- ↑ Backhouse, Constance. Colour-coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900-1950. Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, University of Toronto Press (1999), p. 183

- ↑ Dr. J. Rufus Bratton. "The Eminent Physician of Yorkville in Dying Condition", State (Columbia, South Carolina), Wednesday, September 1, 1897, Page: 8

- ↑ "Mortuary Notice", State (Columbia, South Carolina) Thursday, September 2, 1897, Page: 8