| Rhodes State Office Tower | |

|---|---|

| |

| Former names | State Office Tower |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in Columbus, Ohio since 1972[I] | |

| Preceded by | LeVeque Tower |

| General information | |

| Type | Government offices |

| Architectural style | Modernist, Brutalist |

| Address | 30 East Broad Street Columbus, Ohio |

| Coordinates | 39°57′45″N 82°59′58″W / 39.9626°N 82.9994°W |

| Named for | James A. Rhodes |

| Construction started | May 4, 1971 |

| Topped-out | October 1, 1972 |

| Completed | Mid-1974 |

| Cost | US$66-80 million |

| Owner | State of Ohio |

| Height | 629 ft (192 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Steel, granite, concrete foundation |

| Floor count | 41 3 below ground |

| Floor area | 1,200,000 sq ft (110,000 m2) |

| Lifts/elevators | 22 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Brubaker/Brandt Dalton, Dalton, Little, and Newport |

| Other information | |

| Parking | Underground garages |

| Website | |

| das | |

| References | |

| [1][2][3][4] | |

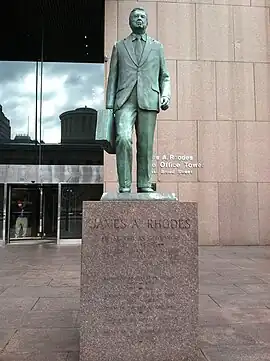

The James A. Rhodes State Office Tower is a 41-story, 629-foot (192 m) state office building and skyscraper on Capitol Square in Downtown Columbus, Ohio. The Rhodes Tower is the tallest building in Columbus and the fifth tallest in Ohio. The tower is named for James A. Rhodes, the longest-serving Ohio governor, and features a statue of Rhodes outside the entrance. The building's interior includes a large open lobby with 22 elevators. Higher floors have offices for numerous state agencies. The tower's 40th floor contains an observation deck, open to the public.

The Rhodes Tower was designed by Brubaker/Brandt and Dalton, Dalton, Little, and Newport in a Modernist style. It was conceived in 1969 as a way to consolidate state offices in one building and give more space to legislative offices in the Ohio Statehouse. Construction spanned from 1971 to 1974; it has held state offices since mid-1974, including the Supreme Court of Ohio until it moved to the renovated Ohio Judicial Center in 2004. The Rhodes Tower was renovated from 2018 to 2022 for energy savings and façade maintenance.

Attributes

The Rhodes State Office Tower sits on Capitol Square in Downtown Columbus, on Broad Street.[5]: 12 It is the tallest building in Columbus, measuring 629 feet (192 m) tall.[6][7] It is also the tallest building housing the state government.[8] The building faces the Ohio Statehouse, the state capitol building, located to its immediate south.[9] A bi-level tunnel connects the basements of the two buildings, with the upper level designed for pedestrians and the lower for vehicles.[10][11] The building's basement contains parking for 78 cars.[11]

As of 2021, the building holds offices for the Ohio Attorney General, Ohio State Treasurer, Ohio Department of Administrative Services, Ohio Office of Budget and Management, Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Ohio Department of Taxation, the Ohio Inspector General, and the Ohio Arts Council.[12][13]

Plaza

The southern portion of the site has a small pedestrian plaza facing Broad Street, partially formed as the building's entrance is set back from underneath the bulk of the building. The plaza includes six trees; the six planted in 1974 were 'Moraine' honey locusts, 25 feet (7.6 m) tall.[14]

The plaza contains a bronze statue titled Governor James A. Rhodes and depicting Jim Rhodes, Ohio's longest-serving governor and the building's namesake.[5]: 12 The six-foot, six-inch statue was originally installed and dedicated on the northeast corner of the Ohio Statehouse grounds in 1982. It was moved to its current location in 1991 as a temporary measure amid renovation of the statehouse. Jim Rhodes was among those who preferred it at the Statehouse, though those in charge of the renovations were in support of its current placement; it remains at the foot of the tower today.[15][16]

Exterior

The Rhodes Tower was designed by Brubaker/Brandt of Columbus and Dalton, Dalton, Little, and Newport of Cleveland.[5]: 12 The skyscraper was designed in a Modernist style, sometimes characterized as Brutalist, featuring the style's characteristic heavy rectilinear masonry.[17] The verticality of the building serves as a foil to the Ohio Statehouse across Broad Street, increasing the horizontal appearance of the Statehouse, and the glass-walled lobby reflects a mirror image of the Statehouse to pedestrians on Broad Street.[18]

The Rhodes Tower has a complex massing and form. It includes a low asymmetrical base, reflecting the scale of the shorter buildings surrounding the tower.[5]: 12 The lower floors of the building were designed to house the Supreme Court of Ohio; the court's chamber there is visible from the exterior with a projecting granite wall, surrounded by glass walls that further emphasize the chamber.[18] The tower has a steel frame above a foundation of concrete-filled steel caissons. The foundation reaches 100 feet (30 m) below the surface to the limestone bedrock. The entire exterior of the Rhodes Tower, the surrounding sidewalk, and the lower part of the building's interior are lined with coarse-grained Milbank granite, quarried in Milbank, South Dakota by the Cold Spring Granite Company and branded as Carnelian granite. The stone is estimated to be 2 billion years old.[11][9] The exterior has 13,108 granite panels,[19] which give varying effects depending on the viewer's angle. The same stone is used on Capitol Square's Huntington Center, and a similar color on the Wyandotte Building nearby.[5]: 12 The rich red stone intensifies the brightness of the white limestone used in the Ohio Statehouse.[18] In 1975, the tower was claimed to be the largest granite structure on Earth.[11] The building also has 3,144 windows with dark gray glass.[19]

The building is topped with radio and television antennae, installed during the building's construction. The initial antennae were for the Columbus Division of Police, Columbus Division of Fire, and the Ohio Educational Television network (the latter was supported by a large circular steel structure).[20] Also at the top of the building are air navigation beacons as well as a rooftop helicopter pad (for official and emergency use only).[11]

The building has suffered minor maintenance issues and fires over its history. In 1989, three fires took place; one extensively damaged much of the 36th floor, with no injuries.[21][22][23] Drinking water taste was an issue for years, leading offices to purchase five-gallon water coolers to use instead.[24] As renovations to the building's façade began in 2017, a 12-by-2-inch piece of granite fell from the building, prompting the surrounding sidewalk to close pending an inspection.[25] In 2015, one of the building's workers contracted Legionnaire's disease; Legionella bacteria was found at safe levels in locations throughout the building, and at a high level only in a basement shower. The water system was cleaned and health officials did not announce if they had concluded the origin of the worker's illness.[26] Controlling temperatures in the building was an issue in the 1970s, especially in the glass-walled offices of the Supreme Court. A burst pipe flooded the chief justice's office in early 1977.[27]

Interior

Rhodes Tower contains 41 stories and 1,048,000 sq ft (97,400 m2) of office space.[11] The building was constructed to accommodate 5,000 workers.[28] As of 2022, approximately 2,600 state employees work in the building.[19]

Its first floor was designed with a five-story galleria-like lobby, a unique feature made possible by the building's elevator placement. The center of the lobby has a winding staircase leading up to the former Supreme Court level as well as two escalators that lead to the basement's restaurant and passage to the Statehouse garage.[17][11] Towards the back of the lobby is a stainless steel recreation of the Great Seal of Ohio.[11] The floorplans of the building are column-free, 144 feet square. All of the building's elevators (20 for passengers and two for freight[11]) and service shafts were designed outside of the square office space, at the north and east (back and side of the building).[10][17] The elevators include express elevators that skip floors between the lobby and 18th floor. One of these elevators malfunctioned in 2021 with no injuries.[29]

The four floors originally for the Ohio Supreme Court, directly above the lobby, were described in 1975 as an impressive "polished steel and glass enclave" with cushioned flaming scarlet carpeting. The main courtroom had leather high-back chairs behind a polished red granite bench. Behind the seats was a smaller version of the steel Ohio seal in the building's lobby. The courtroom connected to a corridor leading to justices' chambers, containing teakwood desks, velvet furniture, spacious work areas, and private individual showers. Each of these chambers was fronted by a wall of glass, and had a private mahogany-paneled elevator.[11] The building's fourth floor contained the Supreme Court's 150,000-volume law library, with teak shelving, plush furniture, custom drapes and scarlet carpeting, as recorded in 1975.[11]

The tower's interior has frequently been used for art exhibits. These include the Young People's Art Exhibit, sponsored by the Ohio Art Education Association in 2001.[30] An Ohio Art League exhibition in 1992 prompted complaints from the building's tenants. Some of the pieces impeded hallways;[31] other works in the exhibit received complaints due to nudity or their statements on sexism and reproductive rights.[32] It was reported in 1973 that tower would feature its own commissioned artwork, at a cost of $300,000 to $400,000, including graphics, sculptures, and tapestries with themes of Ohio history, culture, geography, and resources.[33] In 1974, a proposal aimed for $1,175,000 for paintings, gardens, sculptures, and other artworks, including a rooftop garden and sculpture;[34] $800,000 was estimated to have been spent on the program in June 1974.[35]

Treasurer offices

The building's ninth floor was designed for the offices of the Ohio State Treasurer, including a large and secure bank vault. The treasurer at the time the building opened, Gertrude Walton Donahey, objected to moving into the tower, preferring tradition and historical continuity with her office in the Ohio Statehouse, and alleging that the older bank vaults in the Statehouse would be more secure. The office and vault contents were nonetheless moved to the Rhodes Tower, though in 2007 the treasurer's office was moved back into the Statehouse.[36][37]

Observation deck

The tower's 40th floor contains an observation deck, providing an unobscured panoramic view of Columbus, accessed by a 28-second elevator ride. The attraction is free to the public, requiring only photo IDs in order for lobby staff to grant visitor badges. The floor-to-ceiling viewing windows are located on the north, east, and south sides of the building, and on clear days they give views past the Columbus metropolitan area. Signs by the windows identify notable buildings and sights.[6][38] When the building opened, the deck wrapped around all four sides of the building, though it was altered to allow for more office space on the floor. It is nevertheless one of few observation decks remaining open to the public; areas in the Leveque Tower and One Nationwide Plaza are no longer accessible.[39]

The observation deck supports panoramic views of the surrounding city as well as numerous natural landmarks: the Scioto River, the beginning of the Appalachian Plateau, till plains to the north and south, and the Powell Moraine to the north.[9]

The east-facing hallway on the floor features a 28-foot (8.5 m) mural by local artist Mandi Caskey. The artwork depicts Ohio in four seasons, accompanied by some of its natural symbols, including the white trillium flower, buckeye tree, and white-tailed deer.[6] The work was unveiled in January 2017, and was the first new piece of public art in the building since it opened. Other works in the building will next be replaced, at one or two per year, as some of the 75 works on display are outdated, worn, or damaged.[40]

The view has been described in Secret Columbus as the best panoramic view of the city, and a well-kept secret, given the observation deck's unlikely location in a state office building.[6]

Falcon nest

On the 41st floor, a nesting box with a video feed had been installed for peregrine falcons. The project began in 1989 in hopes of reintroducing the falcons to the area. Similar projects ran in Akron, Dayton, and Cincinnati to support the bird populations, which had severely dropped in the mid-20th century due to pesticide use. The box was moved to the 31st floor of the Vern Riffe State Office Tower (which had its own peregrines) in 2017 to prevent incidents during the renovation of the building's exterior, though the falcons nested in a commercial building on State Street instead.[41][42][43]

One of the hatchlings at the tower, named Buckeye, lived from 1996 to 2009. It was believed to be one of the oldest and most prolific peregrines in the U.S. The falcon flew north as an adult, living for two years at the Case Western Reserve University campus in Cleveland before spending about 12 nesting on Terminal Tower, raising 34 chicks over its lifetime.[44]

History

.jpg.webp)

Planning and construction

The idea for the building began with the Ohio General Assembly, which created a committee to plan for the future use of the Ohio Statehouse, its annex, and any new buildings in 1969. The committee in turn ordered the Ohio Building Authority to construct the tower for the state treasurer, auditor, secretary of state, attorney general, supreme court, and any other state agencies. Legislative leaders supported the move, granting them more space in the Ohio Statehouse.[45]

The new office tower was initially planned to contain 42 stories with an additional three sub-floors. A cafeteria floor was removed in 1970, and the exterior materials were selected – limestone and bronze-tinted glass. The building's cost was estimated at $50-52 million, with groundbreaking on June 1, 1971.[46] The new state offices led the Ohio Building Authority to plan for the demolition of four older buildings it was occupying, which had skyrocketing maintenance costs: the Wyandotte Building, the Ohio Statehouse Annex, and the two former main school buildings of the Ohio Institution for the Deaf and Dumb. The new building would also allow the state to vacate four additional buildings it was using.[47]

In 1971, Democrats were elected to the state's auditor and treasurer offices, after Republicans had previously run them. The new Democratic officials stated their preference that state officials should keep their offices in the Statehouse,[48] and in 1973, they requested that the assembly reverse its decision to move their offices into the new building.[45]

Construction necessitated demolition of the Columbus Board of Trade Building (at the same address), the Outlook Building, and the Spahr Building. In 1971, the site was clear, allowing for construction,[7] which began on May 4, 1971. There was no groundbreaking ceremony, reportedly because the governor declined to participate.[49][50] The building was topped out in October 1972. The first agency to move in was the Department of Administrative Services (DAS), in January 1974. Construction lasted until mid-1974; in the meantime, the DAS worked on the logistics of moving in other agencies. Late in construction, the state decided to reduce the building's height from 42-43 stories to 41; costs rose from the $40 million expected up to $66 million[11] or $80 million.[51]

Opening

When completed, the building became the tallest in Columbus, taking the title from the 1927-built LeVeque Tower.[5]: 43 In the first five years of its operation, it was officially the State Office Tower; governor John J. Gilligan chose the name over 25 others, including the Supreme Court Tower, State Office Building, Buckeye Tower, and George Busche Memorial Tower.[52] It was renamed and dedicated to James Rhodes in 1979.[7] The building earned an honor award from the Columbus chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1975.[53]

The Rhodes Tower was built during the 1970s energy crisis; to combat the oil shortage, the building was designed with light bulbs that would provide up to half of the building's heat,[54][55] and without light switches in many areas, preventing office workers from interfering with the climate controls. In 1980, the Ohio Building Authority found cheaper heating alternatives and installed switches in the building to save on electricity costs.[56]

In September 2001, days after the September 11 attacks took place, the Rhodes Tower was identified among about a dozen other sites potentially vulnerable to terrorism in the Columbus area.[57] One year after the attacks, on September 11, 2002, a contractor was arrested in the building after making a statement that resembled a bomb threat.[58] A bomb threat called in to police caused evacuations in three government buildings downtown, including the Rhodes Tower; a bomb was alleged to be placed on its 13th floor.[59]

The offices and courtroom for the Supreme Court of Ohio were located in the Rhodes Office Tower from 1974 to 2004, having moved from the Judiciary Annex of the Ohio Statehouse. The court left the building for its own facility, the Ohio Judicial Center, in 2004. The move would allow the court to expand from its space on eight floors of the Rhodes Tower into sixteen floors of the Judicial Center.[60]

The Ohio Arts Council moved its offices into the building in 2010; it had previously been based in the Neville Mansion and LeVeque Tower.[13]

From 2018 to 2022, the state government commissioned a renovation of the building. It involved replacing all of the windows on the building, as well as the anchors to its granite panels, some of which were cracked or chipped. 204 of the panels were replaced, and insulation and a vapor barrier were added to the structure. The project was well-managed, ending hours before its deadline and $5 million under its $70 million budget. It was the largest renovation of an Ohio government building since the 1996 Ohio Statehouse renovation. Scaffolding was placed around the tower almost a year prior to the project's official start, and was removed in summer 2021. During this time, restaurants in the surrounding alleys complained that the scaffolds led to a loss in revenue.[19] The project was one of several significant initiatives that earned the building an Energy Star certification in from 2019 to 2021.[61]

For years, the building has been the site of the Fight For Air Climb Columbus event, a fundraiser run by the American Lung Association. In the event, about 400 participants climbed up the tower's 880 steps in an effort to raise awareness and funds for the association.[62] In the 1990s, one of the climbers used the event to break Guinness World Records for fast ascents; his 1994 record was for 53 ascents in just over nine hours.[63]

Reception

The building was positively reviewed at the time of its completion. Architect Richard R. Tully indicated that as Columbus buildings were conservative in design at the time, they age well; he opined that the Rhodes Tower is one of several examples of well-designed buildings that will still look good 50 years from that time.[64]

See also

References

- ↑ "Rhodes State Office Tower". CTBUH Skyscraper Center.

- ↑ "Emporis building ID 119073". Emporis. Archived from the original on 2016-03-07.

- ↑ "Rhodes State Office Tower". SkyscraperPage.

- ↑ Rhodes State Office Tower at Structurae

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Darbee, Jeffrey T.; Recchie, Nancy A. (2008). The AIA Guide to Columbus. Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780821416846.

- 1 2 3 4 Hamper, Anietra (2018-03-15). Secret Columbus: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful, and Obscure. Reedy Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-68106-125-2.

- 1 2 3 Deitch, Linda. "History of Downtown Columbus' tallest building, the Rhodes Tower". The Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on 2021-12-02. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ "Granite signing makes State leaders part of Rhodes Tower history". DAS Update. Ohio Department of Administrative Services. September 27, 2021. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Ruth W. Melvin & Gary D. McKenzie (1997) [1992]. Guide to the Building Stones of Downtown Columbus: A Walking Tour (PDF). Guidebook No. 6. State of Ohio, Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- 1 2 "Preview" (PDF). Architectural Forum: 14. December 1971. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Ionne, Joe (February 2, 1975). "An Inside View". Columbus Dispatch Magazine. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ↑ "Directory of Officials & Resource Guide" (PDF). Clinton County Emergency Management Agency. July 8, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- 1 2 "Ohio Arts Council planning for move to Rhodes Tower". The Columbus Dispatch. July 15, 2010. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Tree Begins Towering Ascent". The Columbus Dispatch. May 3, 1974. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Columbus Mileposts: Dec. 5, 1982 - Praise, protest greet Rhodes at statue unveiling". The Columbus Dispatch. December 5, 2012. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Rhodes Statue May Move Back To Statehouse". The Columbus Dispatch. December 29, 1995. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Ware, Jane (December 20, 2001). "Building Ohio : a traveler's guide to Ohio's urban architecture". Wilmington, OH : Orange Frazer Press. p. 188 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 "Four Towers and the Statehouse". The Columbus Dispatch. December 11, 1983. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Weiker, Jim. "Four years later, Rhodes state office tower renovation wraps up". The Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on 2023-02-21. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ "Police Radio Network Installation Work Set". The Columbus Dispatch. February 12, 1974. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "After-Hours Fire Damages Part Of Rhodes Tower". The Columbus Dispatch. December 23, 1989. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Fire Chases Workers From Rhodes Tower". The Columbus Dispatch. May 1, 1989. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Computers Hit By Fire Work Again". The Columbus Dispatch. December 28, 1989. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Solution Sought For Sour Water - Rhodes Tower". The Columbus Dispatch. October 6, 1993. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Downtown - Chunk of falling facade closes Rhodes Tower area". The Columbus Dispatch. November 23, 2017. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Public health - Legionella bacteria found in state tower". The Columbus Dispatch. February 12, 2016. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Chilling Rumor Warms Up Tower". The Columbus Dispatch. February 2, 1977. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ Betti, Tom; Uhas Sauer, Doreen (2021). Forgotten Landmarks of Columbus. The History Press. p. 64. ISBN 9781467143677.

- ↑ "Rhodes Tower elevator that malfunctioned shouldn't have been in service, inspection records show". 10tv.com. February 10, 2022. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ "Youth Art Lobbies For Attention". The Columbus Dispatch. March 13, 2001. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Artworks In Rhodes Tower Exhibit To Remain". The Columbus Dispatch. June 9, 1992. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Art League Exhibit Draws Complaints". The Columbus Dispatch. June 3, 1992. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "State Office Building To Include Art Works". The Columbus Dispatch. October 18, 1973. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Proposed Decoration Of Tower Is Costly". The Columbus Dispatch. August 28, 1974. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "State Office Tower Cost Jumps 10%". The Columbus Dispatch. June 25, 1974. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Officeholders shun tower for space inside Statehouse - Treasurer following governor in moving base of operations". The Columbus Dispatch. January 6, 2007. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "From Vault to Vault". The Columbus Dispatch. June 1, 1975. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ Jacobson, Todd. "Secret Ohio: James A. Rhodes State Office Tower Observation Deck". www.ohiomagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2023-02-18. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ "GREAT VIEWS OFTEN OUT OF SIGHT". The Columbus Dispatch. September 22, 2002. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Ohio begins to replace public art collection at Rhodes Tower". The Seattle Times. January 19, 2017. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ "Rhodes Tower Work Forces Move Of Peregrine Falcon Nest Box". WCBE 90.5 FM. January 3, 2018. Archived from the original on 2023-02-18. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ "Rhodes Tower Falcons". Susan Levine Books. Archived from the original on 2023-02-18. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ↑ Schladen, Marty. "Work to displace Rhodes falcons". The Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on 2023-02-21. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ James F. McCarty, The Plain Dealer (November 24, 2009). "Cleveland's peregrine falcon perishes after 12 years nesting on the Terminal Tower". cleveland. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- 1 2 "Solon Chides State Office Tower Rebels". The Columbus Dispatch. March 1, 1973. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "State Building's Plans Approved". The Columbus Dispatch. September 30, 1970. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "State Office Building Plan Path Cleared". The Columbus Dispatch. October 4, 1970. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "State Tower, Dear to GOP, Irks Dems". The Columbus Dispatch. January 17, 1971. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "State Office Building Construction Starts". The Columbus Dispatch. May 4, 1971. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Rare Start". The Columbus Dispatch. May 2, 1971. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Columbus Mileposts: Jan. 28, 1974 - Agency planned move to State Office Tower". The Columbus Dispatch. January 28, 2012. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Skyscraper Named State Office Tower". The Columbus Dispatch. November 21, 1973. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "AIA Chapter Honors Eight". The Columbus Dispatch. February 26, 1975. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Energy a High Rise Puzzle". The Columbus Dispatch. November 19, 1973. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Lights Through the Night For Heat". The Columbus Dispatch. February 19, 1974. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Lights Will Dim In Office Tower". The Columbus Dispatch. February 11, 1980. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "SEVERAL AREA SITES POTENTIAL TARGETS". The Columbus Dispatch. September 16, 2001. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "CONVICTED MAN MUST STAY OUT OF U.S. FOR 10 YEARS - INS to decide fate of family of illegal immigrant who caused bomb scare". The Columbus Dispatch. September 25, 2002. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "DOWNTOWN BOMB SCARE DISRUPTS WORKDAY - 3 recent incidents seem to be unrelated". The Columbus Dispatch. February 26, 2004. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "REHAB SUPREME - High court's new home is worthy showpiece". The Columbus Dispatch. February 16, 2004. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "James A. Rhodes State Office Tower earns Energy Star certification - Sidney Daily News". www.sidneydailynews.com. April 22, 2021. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ↑ "Hundreds climb 880 stairs at Rhodes Tower for Fight for Air Climb fundraiser". NBC4. February 16, 2019. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Symphony player climbs tower for others". The Columbus Dispatch. January 31, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "How Should Our City Grow?". The Columbus Dispatch. January 2, 1983. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.