James H. Howard | |

|---|---|

Col. James H. Howard in 1945 | |

| Born | April 8, 1913 Canton, Republic of China (now Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) |

| Died | March 18, 1995 (aged 81) Bay Pines, Florida, U.S. |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Air Force United States Army Air Forces American Volunteer Group United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1938–1941 (USN) 1941–1942 (AVG) 1942–1966 (USAAF/USAF) |

| Rank | Ensign (Navy) Brigadier General (Air Force) |

| Commands held | 356th Fighter Squadron 354th Fighter Group 96th Bombardment Wing |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Medal of Honor Distinguished Flying Cross (2) Bronze Star Air Medal (10) |

| Alma mater | Pomona College |

James Howell Howard (April 8, 1913 – March 18, 1995) was a general in the United States Air Force and the only fighter pilot in the European Theater of Operations in World War II to receive the Medal of Honor — the United States military's highest decoration.[1] Howard was an ace in two operational theaters during World War II, with six kills over Asia with the Flying Tigers of the American Volunteer Group (AVG) in the Pacific, and six kills over Europe with the United States Army Air Forces.[2] CBS commentator Andy Rooney, then a wartime reporter for Stars and Stripes, called Howard's exploits "the greatest fighter pilot story of World War II".[3][4] In later life, Howard was a successful businessman, author, and airport director.

Early life

Born on April 8, 1913, in Canton, China, where his American parents lived at the time while his ophthalmologist father was teaching eye surgery there, Howard returned with his family to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1927. After graduating from John Burroughs School in St. Louis, he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Pomona College in Claremont, California, in 1937, intending to follow his father into medicine.[3][5] Shortly before graduation, however, Howard decided that the life of a Naval Aviator was more appealing than six years of medical school and internship, and he entered the United States Navy as a naval aviation cadet.

Military career

United States Navy

Howard began his flight training in January 1938 at Naval Air Station Pensacola, earning his wings a year later.[5] In 1939, he was assigned as a U.S. Navy pilot aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, based at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Flying Tigers

In June 1941, he left the Navy to become a P-40 fighter pilot with the American Volunteer Group (AVG), the famous Flying Tigers, in Burma.[5] He flew 56 missions and shot down 6 Japanese warplanes.[1]

United States Army Air Forces

After the Flying Tigers were disbanded on July 4, 1942, Howard returned to the U.S. and was commissioned a captain in the Army Air Forces. In 1943, he was promoted to the rank of major and given command of the 356th Fighter Squadron in the 354th Fighter Group, based in the United Kingdom.

On January 11, 1944, Howard led three squadrons of 354th FG P-51s on an escort mission to support bombers on the target leg at Oschersleben, Germany. The bombers had completed their target run and were already in trouble when Howard spotted them. After dispensing the other two squadrons to protect middle and rearward bomber formations, Howard's squadron flew towards the lead formation and broke up into flights.[6] After the initial contact, Howard became separated from his flight[5] and then from his wingman[6] and flew unaccompanied into some 30 Luftwaffe fighters that were attacking a formation of American B-17 Flying Fortress bombers.[3][7] For more than a half-hour, Howard defended the heavy bombers of the 401st Bomb Group against the swarm of Luftwaffe fighters, repeatedly attacking the enemy and shooting down as many as six.[7] Even after three of his four guns were out of action, he continued to dive on enemy airplanes.[7] The leader of the bomber formation later reported, "For sheer determination and guts, it was the greatest exhibition I've ever seen. It was a case of one lone American against what seemed to be the entire Luftwaffe. He was all over the wing, across and around it. They can't give that boy a big enough award."[5]

The following week, the Army Air Forces held a press conference in London at which Major Howard described the attack to reporters, including the BBC, the Associated Press, CBS reporter Walter Cronkite, and Andy Rooney, then a reporter for Stars and Stripes. The story was a media sensation, prompting articles such as "Mustang Whip" in the Saturday Evening Post, "Fighting at 425 Miles Per Hour" in Popular Science, and "One Man Air Force" in True magazine. "An attack by a single fighter on four or five times his own number wasn't uncommon," wrote a fellow World War II fighter pilot in his postwar memoirs of Howard's performance, "but a deliberate attack by a single fighter against thirty-plus enemy fighters without tactical advantage of height or surprise is rare almost to the point of extinction."[8] The following month, Howard was promoted to lieutenant colonel and in June 1944, he was presented the Medal of Honor by General Carl Spaatz for his January 11 valor. That same month, Howard helped direct fighter cover for the Allies' Normandy landings on D-Day.[3]

In January 1945, Howard was promoted to colonel and assigned as base commander of Pinellas Army Airfield (now St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport) in Florida.[3]

United States Air Force

With the establishment of the United States Air Force as a separate service in 1947, then-Colonel Howard was transferred to it. In 1948, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general in the U.S. Air Force Reserve, commanding the Air Force Reserve's 96th Bombardment Group.[5]

Later years

As a civilian after the war, Howard was Director of Aeronautics for St. Louis, Missouri, managing Lambert Field while maintaining his military status as a brigadier general in the United States Air Force Reserve. He later founded Howard Research, a systems engineering business, which he eventually sold to Control Data Corporation.[5] He married Mary Balles in 1948 in a military wedding ceremony. They later divorced, and Howard then married Florence Buteau.

.jpg.webp)

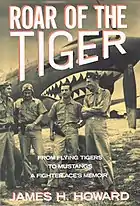

In the 1970s, Howard retired to Belleair Bluffs in Pinellas County, Florida.[1] In 1991, he wrote an autobiography, Roar of the Tiger, chiefly devoted to his wartime experiences.[5] On January 11, 1994, the 50th anniversary of the Oschlersleben attack, the Board of County Commissioners in Pinellas County proclaimed "General Howard Day" and presented him with a plaque.[9] A permanent exhibit honoring General Howard was also unveiled in the terminal building of the county's St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport.[4][10] Another exhibit paying tribute to Howard was subsequently dedicated at his high school alma mater, John Burroughs School in St. Louis.

On January 27, 1995, Howard made his last public appearance when he was guest of honor at the annual banquet of the West Central Florida Council of the Boy Scouts of America, in Clearwater, Florida. He died six weeks later at the nearby Bay Pines Veterans Hospital, survived by two sisters. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[1]

Honors

Howard Avenue in the Market Common District of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, is named in tribute to Howard, who was a commander of the relocated 354th Fighter-Day Group at nearby Myrtle Beach Air Force Base.[11] There is a memorial marker with photos and an inscription in Market Common Valor Memorial Garden at the intersection of Hackler Street and Howard Avenue: 33°40.062′N 78°56.368′W / 33.667700°N 78.939467°W.[12]

Summary of aircraft destroyed

| Date | # | Type | Location | Aircraft flown | Unit Assigned | Air/Ground |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 3, 1942 | 3 | Nakajima Ki-27 | Rahang, Thailand | P-40C | 2 PS,[5] AVG | Ground |

| January 19, 1942 | 0.15 | Mitsubishi Ki-21 | Mesoht, Burma | P-40C | AVG | Air |

| January 24, 1942 | 1 | Ki-27 | Yangon, Burma | P-40C | AVG | Air |

| July 4, 1942 | 1 | Ki-27 | Hengyang, China | P-40E | AVG | Air |

| December 20, 1943 | 1 | Messerschmitt Bf 109 | Bremen, Germany | P-51B Mustang | 356 FS, 354 FG | Air |

| January 11, 1944 | 2 | Messerschmitt Bf 110 | Oschersleben, Germany | P-51B | 356 FS, 354 FG | Air |

| January 11, 1944 | 1 | Focke-Wulf Fw 190 | Oschersleben, Germany | P-51B | 356 FS, 354 FG | Air |

| January 30, 1944 | 1 | Bf 110 | Braunschweig, Germany | P-51B | 356 FS, 354 FG | Air |

| April 8, 1944 | 1 | Fw 190 | Braunschweig, Germany | P-51B | 354 FG[13] | Air |

- All information on enemy aircraft damaged and destroyed is from Stars and Bars.

Military awards

Howard received the following awards:

| |||

| U.S. Air Force Command pilot badge | |||||||||||

| Medal of Honor | Distinguished Flying Cross with bronze oak leaf cluster | ||||||||||

| Bronze Star Medal | Air Medal with one silver and three bronze oak leaf clusters |

Air Medal (second ribbon required for accoutrement spacing) | |||||||||

| Air Force Presidential Unit Citation | American Defense Service Medal with service star |

American Campaign Medal | |||||||||

| Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with bronze campaign star |

European–African–Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with two bronze campaign stars |

World War II Victory Medal | |||||||||

| National Defense Service Medal with service star |

Air Force Longevity Service Award with four bronze oak leaf clusters |

Armed Forces Reserve Medal with silver hourglass device | |||||||||

| Order of the Sacred Tripod 6th Grade (Republic of China) |

Order of the Cloud and Banner 6th Grade (Republic of China) |

China War Memorial Medal (Republic of China) | |||||||||

Medal of Honor citation

The citation accompanying the Medal of Honor awarded to Lieutenant Colonel James H. Howard on 5 June 1944, by Lieutenant General Carl Spaatz reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty in action with the enemy near Oschersleben, Germany, on 11 January 1944. On that day Col. Howard was the leader of a group of P-51 aircraft providing support for a heavy bomber formation on a long-range mission deep in enemy territory. As Col. Howard's group met the bombers in the target area the bomber force was attacked by numerous enemy fighters. Col. Howard, with his group, at once engaged the enemy and himself destroyed a German ME. 110. As a result of this attack Col. Howard lost contact with his group, and at once returned to the level of the bomber formation. He then saw that the bombers were being heavily attacked by enemy airplanes and that no other friendly fighters were at hand. While Col. Howard could have waited to attempt to assemble his group before engaging the enemy, he chose instead to attack single-handed a formation of more than 30 German airplanes. With utter disregard for his own safety he immediately pressed home determined attacks for some 30 minutes, during which time he destroyed 3 enemy airplanes and probably destroyed and damaged others. Toward the end of this engagement 3 of his guns went out of action and his fuel supply was becoming dangerously low. Despite these handicaps and the almost insuperable odds against him, Col. Howard continued his aggressive action in an attempt to protect the bombers from the numerous fighters. His skill, courage, and intrepidity on this occasion set an example of heroism which will be an inspiration to the U.S. Armed Forces.[14]

See also

References

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

- 1 2 3 4 Wolfgang Saxon (1995-03-22). "Gen. James Howard, 81, Dies; Medal Winner in Aerial Combat". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ↑ Christopher Shores (1975). Fighter Aces. Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0517573235.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "One of War's Greatest Pilots to Command Pinellas Air Field". St. Petersburg Times. January 21, 1945. Retrieved October 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Christina K. Cosdon (1996-11-03). "New exhibit at airport honors hero". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 2008-06-07. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Howard, James H. (1991). Roar of the Tiger. New York: Orion Books. ISBN 978-0-517-57323-5. OCLC 22452550.

- 1 2 Grant, Rebecca (1 Nov 2010). "One-Man Air Force". Air & Space Forces.

- 1 2 3 Frederick Graham (January 19, 1944). "One-Man Air Force Belittles His Feat" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ↑ Richard E. Turner (1983). Big friend, little friend. Mesa, Ariz.: Champlin Fighter Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-912173-00-9.

- ↑ Roger Clendening II (1994-01-11). "WWII pilot will be honored today". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ↑ "Airport Guide – History". St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport. 1997. Archived from the original on 2008-06-15. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ↑ Lesta Sue Hardee (2014). Legendary Locals of Myrtle Beach. Legendary Locals. ISBN 978-1467101431.

- ↑ Herrick, Michael (2017-03-19). "The Historical Marker Database". Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ USAF (1978). "USAF Historical Study No. 85, USAF credits for the destruction of enemy aircraft, World War II". Air Force Historical Research Agency.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor recipients - World War II". United States Army Center of Military History. 2007-07-16. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

Further reading

- Freeman, Roger A. (1994). UK Airfields of the Ninth Then and Now. London: Battle of Britain Prints International. ISBN 9780900913808. OCLC 32201425.

- Mclaughlin, William (2016-02-02). "'The greatest fighter pilot story of WWII' held off 30 German fighters from attacking a squadron of B-17 bombers for over half an hour". War History Online. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

External links

Media related to James H. Howard at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to James H. Howard at Wikimedia Commons