James Ingram | |

|---|---|

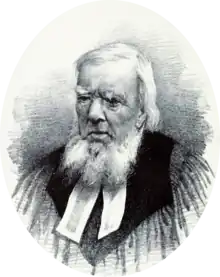

James Ingram from Disruption Worthies[1] | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 3 April 1776 |

| Died | 3 March 1879 |

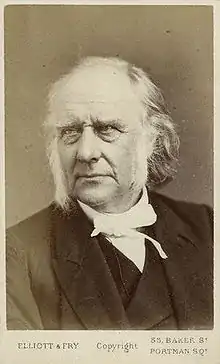

James Ingram (3 April 1776 - 3 March 1879) was a Church of Scotland minister who spent most of his life working in the parishes of Fetlar and Unst. At the Disruption he joined the Free Church. His was sometimes known as the Patriarch of the Free Church. He is remembered for his long life as he lived till within a few weeks of completing his 103rd year. He came from a long-lived family: his father lived to the age of 100, and his grandfather to 105. Additionally he is remembered as the sitter in works of art, including a painting by Otto Leyde. He was also photographed by Charles Spence of Lerwick. He wrote the New Statistical Account for the parish of Unst in 1831.

Early life and ancestry

James Ingram of Unst, the north-most island of Shetland, and the most northerly point of Her Majesty's dominions, was for many years the father of the Free Church. Dr Ingram, the oldest minister of the Gospel in the British Isles at his death, was not a native Shetlander. He was born in Logie Coldston, Aberdeenshire, on 3 April 1776, and lived till within a few weeks of completing his 103rd year. He came of a long-lived family. His father lived to the age of 100, and his grandfather to 105. Both of them spent their long years on the same farm, in the Daugh, parish of Logie Coldston.[1] His mother was Jean Reid, the farm being at Donough-more, Logie-Colstone.[2]

Education

James Ingram received his early education in the parish school of Tarland, and afterwards in the Grammar School of Old Aberdeen. He entered upon his Arts curriculum in King's College there, when fifteen years of age, and was a distinguished student, carrying off the highest competition bursary of his entrance session. He commended himself by his diligence and talent to the whole professorial body, and particularly to Dr Jack, then the Principal of the college, and during life the warm friend of his promising pupil. He began his Divinity course at Aberdeen in 1795, and the following year he was appointed tutor to the family of Mrs Ursula Barclay, widow of the parish minister of Unst, obtaining in this way his first introduction to the island where he laboured as a minister for more than half-a-century.[3][4][1] He graduated with an M.A. (26 March 1796[5]) and was licensed by the Presbytery on 26 June 1800.[2] Supporting himself for the most part by his salary as a teacher, he continued his attendance at the Divinity Hall, from time to time, till the year 1800, when he was licensed as a probationer by the Presbytery of Shetland.[1]

Church of Scotland ministry

On Fetlar

His first appointment as a minister of the Gospel, was to be assistant to the Rev. James Gordon, minister of Fetlar and North Yell, on whose death he was presented to the vacancy by the patron, Lord Dundas.[1] He was ordained to Fetlar on 4 August 1803 being presented by Laurence, Lord Dundas.[6]

After his ordination, he was married to Mary, daughter of Mrs Barclay, and they had a family of four daughters and three sons.[4] The manse was in Fetlar, but having charge of the congregation of Yell also, Mr Ingram had to cross and re-cross almost weekly, the channel, six miles broad, which separates the two islands. He worked hard, preaching and visiting and catechising from house to house, with all the more diligence because it was impossible to tell how long it might be before the warring elements might permit of his next visit.[1]

On Unst

In 1821, he obtained some relief. The church of Unst became vacant, and the people cast their eyes upon the minister of Fetlar, as the man best known to them. Lord Dundas was pleased to have the opportunity of again doing a kindness to Mr Ingram; and Ingram was settled there in 1821, to remain, for many years.[1] He was admitted to that parish on 14 September 1821.[2] In 1831 there were 2909 people living in the parish.[7]

The new pastor did not enter upon another man's line of things made ready to his hand. Previous to the time of the Haldanes and others, who in the beginning of this century, preached the Gospel in these far-off islands of the North Sea, this Ultima Thule of the Romans was as dreary in its spiritual as in its physical condition. The island of Unst in particular, so far as the ministry was concerned, had known nothing of religion except in the form of Moderatism, and the virtuous life which was the theme of the pulpit ministrations was rarely exemplified in the habits of the people. Mr Ingram may almost be said to have re-Christianised Unst. He found the people grossly ignorant, and he established schools. He found them addicted to intemperance, through the facilities offered for smuggling by foreign vessels, as well as through the entire want of intellectual resources, and he founded a temperance society which entirely changed the habits of the greater part of the people.[1]

He was an instructive, earnest, and faithful preacher of the Word, and from his first entrance among his flock, he instituted the practice of regular visitation and catechising. The ordinance of Church discipline was also revived, and became a subordinate but real means of grace. His labours were not in vain in the Lord. The outward reformation of manners was not the only outcome of his fidelity as a preacher and a pastor. There were those on Unst who could speak of him as their spiritual father.[1]

In 1838, Mr Ingram's son was associated with his father in the pastorate by his steady friend, Lord Zetland, moved, as in the case of the senior minister, by the free voice of the people as well as by his own inclination.[1] In 1831 the New Statistical Account of the parish was written. Both James Ingram and John Ingram are named on it.

At the Disruption

Ingram joined the Free Church in 1843 (though he had formerly seconded a motion in the Synod for the removal of the Veto Act). He was a minister of the Free Church on Unst from 1843 to 1879.[2]

In number of years, Mr Ingram, senior, was an old man at the date of the Disruption. He was then sixty-seven. But his eye was not dim, nor his natural force abated. His was sometimes known as the Patriarch of the Free Church although others like Robert Lorimer were older. He was as forward and decided as his son in taking his side in the conflict which came to a climax in 1843. And this, although he held strong views in favour of church establishments founded on a Scriptural basis, and, although the difficulties of erecting new church buildings and organising a new congregation were peculiarly formidable in a place where poverty is extreme, most of the people being in a chronic state of debt to the landowners and merchants, seldom fingering money, but bartering their labour for articles of necessity, and sometimes — against their will — for articles of superfluity. A large majority of the natives of Unst, however, encouraged these ministers by their adherence, and by their material support as far as their slender resources permitted. The peculiarity of their position, so remote from the stimulus and fellowship of brethren like-minded, came at last under the notice of Thomas Chalmers. For several months the ministers, father and son, had to conduct Divine worship in the open air, and, afterwards, the congregation and Sabbath school had to content themselves with the precarious shelter of a tent. Chalmers, on hearing of the circumstances, used his influence with the Countess of Effingham (Charlotte Primrose - c. 1776 – 17 September 1864) to such good purpose that her ladyship provided funds for the erection of two churches, one on the east and the other at the south end of the island.[1]

Out of 1100 communicants at Unst, 1000 joined the Free Church. It turned out that two churches were required, owing to the position of the population in different parts of the island. The difficulty would have been great, but it was met by one of these churches that at Uyasound being erected chiefly by the liberality of the Countess of Effingham. At the opening of the other church, in November, 1843, a striking incident took place. The tent under cover of which the congregation had worshipped, during summer and autumn, was carried away by a furious tempest on the very day when for the first time the people entered their new church.[8]

Old age

In 1864 the University of Glasgow conferred upon Mr Ingram the Degree of D.D. (Glasgow, 12 February 1864),[2] while he was still in the exercise of his ministry. The last time he ascended the pulpit was in 1875. It was the failure of memory and of sight that prevented him preaching afterwards. His voice was as strong as ever, and he was as much at home as ever in prayer; it was only in his pulpit address that he was not his former self.[1]

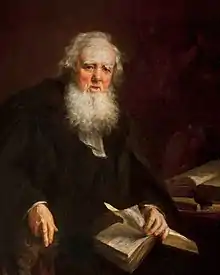

There were others besides the Senatus Academicus of Glasgow who felt it an honour to themselves to honour the face of the old man. Thomas Guthrie and his son, the minister of Liberton Free Church, paid a visit to Dr Ingram in 1871, and greatly cheered the heart of their venerable friend by their genial company and conversation. On his return to Edinburgh, Dr Guthrie set about the raising of a subscription for a portrait of Dr Ingram, and Mr Otto Leyde went to the Free Church Manse of Unst to execute the commission assigned to him. He succeeded in producing a characteristic likeness, life size, and the portrait having been presented to the Free Church, once adorned the walls of the Common Hall of the New College, Edinburgh. A smaller replica of this canvas was taken by the artist, and, along with a silver tea service, was presented to Dr Ingram, to be preserved as an heir-loom in the family.[1][9]

In 1886 the Methodist Sarah Squire came to Unst and was welcomed by James Ingram.[10]

In old age he lost both his sight and his hearing.[11] With all his active labours as a pastor, he had found time to keep up his early studies in theology and classics, and to store his mind with general information. To his hundredth year he could repeat long passages from favourite Latin authors, and regale himself with texts from the Hebrew as well as the Greek Scriptures. As Hebrew, strange to say, was no part of the curriculum of the Aberdeen College when he was a student, he became a self-taught Hebrew scholar, after the age of sixty, and acquired even a critical acquaintance with the language. He mastered German also, later in life.[1]

On his hundredth birthday there was a celebration of a soiree in the Free Church of the people of Unst and the surrounding islands.[12] It took place in the Hillside Free Church and was attended by over 600 people.[13]

During the winter of 1878–79, the cold compelled him to keep his room, but not till within twelve hours of his last breath was there any symptom of serious illness. He died on 3 March 1879.[1]

Family

Ingram is mentioned on Grant's Families of Barclay[4] and Spence of Hammer.[14] The Ecclegen website also has an Ingram tree.

James Ingram married 18 September 1803, Mary (died 9 February 1859), daughter of James Barclay, minister at Unst, and had issue —

- Christian, born 27 April 1805 (married Gilbert Spence of Hammer)

- Charlotte Barclay, born 20 April 1806 (married Andrew Smith of Smithfield, Fetlar)

- John, minister at Unst, born 9 February 1807, died 15 November 1892 who married

- (1) 5 September 1837, Margaret Blair Hutchison, who died 7 January 1858, and had issue —

- James William, born 1 July 1838, died young

- Barbara, born 28 October 1840; (married Robert Shepherd of British Linen Bank, Dundee)

- Mary, born 16 November 1842 (married Peter Macgregor, Free Church minister at Uyeasound, Unst)

- Margaret (twin) born 16 November 1842 (married James Y. Thirde, U.P. minister at Muirton, Laurencekirk [afterwards at Huntsville, Ontario, Canada])

- (2) 1 June 1860, Frances Duff Hepburn Wisdom (died at Hillside, Baltasound, 20 December 1925, aged 94), and had issue —

- James William, in Canada, born 29 August 1862

- Francis Charles, in Canada, born 1863

- Caroline Augusta, born 7 September 1864 (married David Morice Pittendreigh)

- Isobel Margaret, born 8 April 1866, died February 1882

- John Archibald, born 1868

- Frances Charlotte Jean, born 31 March 1870 (married 20 December 1898, Donald Alexander Macdonald, U.F. minister of Kilmuir, Skye)

- Louisa Ann, born 13 March 1872 (married Laurence Jamieson)

- (1) 5 September 1837, Margaret Blair Hutchison, who died 7 January 1858, and had issue —

- Jean, born 4 November 1809 (married James Smith of Clivocast, M.D.)

- Margaret, born 22 October 1812, died unmarried

- William Barclay, born 1 March 1815, died abroad.[2]

New Statistical Account of the Unst parish

In 1831 the account of the parish includes:[16]

Much has been said, and much has been written, by men very superficially acquainted with the state of the country, about the wretchedness, the enslaved, and oppressed state of the peasantry. They have had all their information from hearsay, and have not given themselves the trouble to inquire after the truth, where they might have had it impartially stated to them ; and the consequence has been, that they have geen greatly imposed upon, and they, in their turn, have imposed upon others. They who have lived long amongst the people, and are intimately acquainted with their ways and means, and have seen the comforts they enjoy, can bear the most ample testimony to the fact, that there are but few of Her Majesty's subjects, of the same class, who are treated in a more kindly and indulgent manner by their superiors ; who enjoy so much liberty; who pass through life with so little labour or care; or who have more reason to be contented with the situation and circumstances a kind Providence has assigned them. They do not live in affluence ; but they seldom want the necessaries, and they have many of the luxuries of life, with one-half of the toil that people of their class are doomed to undergo, in more genial climes.

— Ingram & Ingram 1831 NSA

However a footnote says:[17]

Since this Account was drawn up, the circumstances of the people have been sadly altered. A general failure of the crops, for five or six years in succession, has reduced them to great poverty, and it must he long, even under the most favourable circumstances, before they can regain their former state.

— Ingram & Ingram 1831 NSA

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Wylie 1881.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scott 1928.

- ↑ Scott 1928, p. 299.

- 1 2 3 Grant 1893, p. Barclay.

- ↑ Anderson 1893.

- ↑ Scott 1928, p. 296.

- ↑ Ingram & Ingram 1841, p. 41.

- ↑ Brown 1893.

- ↑ Guthrie 1874.

- ↑ Squire 1886.

- ↑ obituary 1879.

- ↑ 100th 1876.

- ↑ London News 1876.

- ↑ Grant 1893, p. Spence.

- ↑ Mouat & Barclay 1791.

- ↑ Ingram & Ingram 1841, pp. 41-42.

- ↑ Ingram & Ingram 1841, pp. 42.

Sources

- Anderson, P. J., ed. (1893). Officers and graduates of University & King's College, Aberdeen, 1495-1860. Aberdeen: New Spalding Club. p. 264.

- Brown, Thomas (1893). Annals of the disruption with extracts from the narratives of ministers who left the Scottish establishment in 1843 by Thomas Brown. Edinburgh: Macniven & Wallace. pp. 458-459, et passim.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Gordon, Thomas (1909). "Longevity and length of incumbency of clergymen in the Church of Scotland 1871-08-12". Notes and Queries. 4. 8 (189): 119.

- Grant, Frances J. (1893). The County Families Of The Zetland Islands. Lerwick: T & J Manson.

- Guthrie, Thomas (1874). Autobiography of Thomas Guthrie, D.D., and memoir by his sons. Vol. 2. New York: R. Carter and brothers. pp. 453-454.

- Ingram, James; Ingram, John (1841). "Parish of Unst". The new statistical account of Scotland. [electronic resource]. Vol. 15. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons. pp. 36–53.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Latey, John Lash, ed. (1876). "A Northern Centenarian". The Illustrated London News 1876-04-29. Vol. 68. London: Illustrated London News. pp. 421-422.

- Mouat, Thomas; Barclay, James (1791). The Statistical Account of Scotland. Vol. 5. Edinburgh : Printed and sold by William Creech; and also sold by J. Donaldson, and A. Guthrie, Edinburgh; T. Cadell, J. Stockdale, J. Debrett, and J. Sewel, London; Dunlop and Wilson, Glasgow; Angus and Son, Aberdeen. pp. 182–202.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Scott, Hew (1928). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 7. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. pp. 300-301.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Sigma (1909). "Longevity and length of incumbency of clergymen in the Church of Scotland 1871-08-12". Notes and Queries. 5. 11 (285): 466.

- Squire, Sarah (23 January 1886). The Friend; A Religious and Literary Journal 1886-01-23. Vol. 59. Open Court Publishing Co. p. 193.

- Wylie, James Aitken, ed. (1881). Disruption worthies: a memorial of 1843, with an historical sketch of the free church of Scotland from 1843 down to the present time. Edinburgh: T. C. Jack. pp. 325–330.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - The Bombay Guardian, 29 April 1876. Bombay: The Bombay Guardian. 1876. p. 68.

3rd column

- The Sunday Magazine. Vol. 8. London: Isbester & Company. 1879. p. 360.

obituary