James Joseph Brown | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) | |

| Born | September 27, 1854 |

| Died | September 5, 1922 (aged 67) |

| Occupation(s) | Mining engineer, investor, socialite |

| Years active | 1877–1922 |

| Known for | Miner, made rich by Little Jonny mine in Leadville |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Tobin (m. 1886, sep. 1909) |

| Children | 2 |

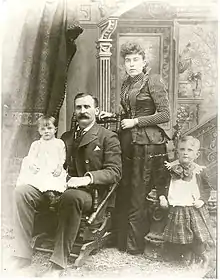

James Joseph "J.J." Brown (September 27, 1854 – September 5, 1922), was an American mining engineer, inventor, and self-made member of fashionable society. His wife was RMS Titanic survivor Margaret Brown.

Early life

Brown was born in Waymart, Pennsylvania on September 27, 1854.[1][2]: 87 [lower-alpha 1] His father, James Brown, was an Irish immigrant who settled in Pennsylvania in 1848. There, he met Brown's mother, Cecilia Palmer, who was a schoolteacher.[1] Soon after he was born, Brown's family moved to Pittston, Pennsylvania.[1][2]: 87 Brown first received an education from his mother and he later studied at St. John's Academy.[2]: 87 [3] In his biography by Ferril, Brown is said to have paid for night school in Pennsylvania to attain an education.[1]

Career

Brown left home at the age of 23 and worked on a farm in Nebraska.[2]: 87 [4]: 27 In 1877, during the Black Hills Gold Rush, Brown went to Deadwood Gulch in the Black Hills of the Dakotas in 1877 and was engaged in placer and quartz mining.[1][4]: 27 At that time, the area was the frontier and subject to conflicts between the miners and Native Americans.[1][2]: 87

Brown came to Colorado in 1880, mining in Georgetown, Aspen and Ashcroft.[1] His brother Edward joined him in the Ashcroft-Aspen area, where he lived for two years.[2]: 88

| Articles |

|---|

| People |

| Mines |

| Related articles |

Brown then went to Leadville.[1] Once the surface ore had been thoroughly gleaned by previous miners, Brown found that mining required knowledge of geology, ore deposits, and mining to be successful and he studied books to become more proficient.[2]: 88 Brown had a "special genius for practical and economic geology," which he used to identify and mine underground properties that subsequently became their most valuable properties.[1] He became an increasingly adept and successful miner[3] becoming a foreman of the Louisville Mine by 1886.[5]

He was hired by Eben Smith and David Moffat to operate their largest mining enterprises,[1] becoming the superintendent of the Maid of Erin and Henrietta mines by 1888.[4]: 27 [5]

Leadville was a successful mining center, producing gold, lead, and silver. It was one of the world's largest and most lucrative silver camps. The Silver Boom flourished in the 1880s.[6]

Little Jonny mine

By 1892, Brown was an investor and board member of the Ibex Mining Company that owned the Little Jonny mine.[7] Initially, silver was mined at Little Jonny.[8] The Silver Boom came to an end in 1893 following the collapse of silver prices caused by the repeal of Sherman Silver Purchase Act.[6] Silver mines closed and the state fell into a deep economic depression.[6][7] In Leadville, 90% of the miners were unemployed.[9] While the price of silver fell, the price of gold went up.[7]

_(17161825282).jpg.webp)

After the silver collapse, John F. Campion hired Brown to find a solution for the mine's shafts that continually filled with dolomite sand[10][11] with the intention of mining gold at Little Jonny.[7][8] Brown's engineering efforts proved instrumental in the production of a substantial gold and copper seam at the mine.[12] The gold was particularly pure.[5] Brown, who was the superintendent of all the Ibex properties, devised a method of using baled hay and timbers to stop cave-ins. His invention paid off. When the Little Jonny mine opened, vast quantities of high-grade copper and gold were found.[13] It was reported to be among the most substantial gold strikes in the country at the time[14] and helped trigger economic recovery in Leadville and throughout the state.[14]

By October 29, 1893, the Little Jonny was shipping 135 tons of gold ore per day. Brown was awarded 12,500 shares. The Ibex Company and its owners, including the Browns, became extraordinarily wealthy.[5][8]

Entrepreneur

After serving Smith and Moffat for 14 years, in 1894, Brown decided to operate his own mining enterprises in Leadville and other locations. He moved to Denver that year and continued to advise Moffat and others, which led to the first major mining boom in the Creede area.[1] He was the director and one of the major owners of the Ibex Mining Company (Little Jonny Mine) and had mining enterprises in Leadville, other Colorado sites, Arizona, the Southwest,[1] Cuba, and Mexico.[5] He became one of wealthiest mine owners in Colorado.[1]

Ice Palace

Brown, whose Little Jonny Mine continued to produce gold, sought to save Leadville by creating an Ice Palace to draw tourism. Opening in January 1896, it drew tourists from across the country and Europe, and operated until March 28, 1896. Three railroads brought visitors to Leadville, where there was a wide range of entertainment, winter sports, and contests.[6]

Beet sugar production

Brown along with other successful miners sought to diversify their holdings to include agricultural products. Sugar beets were suited for Colorado's arid climate.[4]: 15 Along with Eben Smith and others, Brown was an investor and director of the Colorado Sugar Manufacturing Company, which was established in 1899.[4]: 15, 26 The Great Western Sugar Company was founded by the same miners a few years later. It became the country's largest supplier of beet sugar by 1978.[4]: 15

Personal life

Brown married Margaret Tobin on September 1, 1886, in Leadville's Annunciation Church.[15] They first settled in Leadville, Colorado but moved closer to the mines on Iron Hill in the rugged Stumpftown (now a ghost town). After the birth of their son, the Browns moved back into Leadville, living at 320 Ninth Street and then 322 Seventh Street.[2]: 91, 94 As Brown became more successful, the family enjoyed the life of the upper middle class and sent their children to school in Paris.[2]: 132

In 1894, the Browns moved to Denver, Colorado, buying a $30,000 Victorian mansion in Denver's wealthy Capitol Hill neighborhood. In 1897, they built a summer mansion Avoca Lodge in Southwest Denver, near Bear Creek.[5][16] The couple enjoyed the opera and theatre and Brown was a member of the Denver Athletic Club and the Denver Country Club.[5]

Margaret was later known as The Unsinkable Molly Brown, having survived the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912.[3]

Children

The Browns had two children:

- Lawrence Palmer "Larry" Brown (August 30, 1887 – April 2, 1949) was born in Hannibal, Missouri. Larry married Eileen Elizabeth Horton in 1911 in Kansas City, Missouri. They had two children, Lawrence Palmer "Pat" Brown Jr. and Elizabeth "Betty" Brown. The marriage failed and Larry married actress Mildred Gregory in 1926. Larry studied at the Colorado School of Mines, worked in the mining trade, and took over his father's interests after his death.[17]

- Catherine Ellen "Helen" Brown (July 22, 1889 – September 18, 1970) was born in Leadville, Colorado.[5] She married George Joseph Peter Adelheid Benziger (1877–1970) on April 7, 1913 in Chicago, Illinois, with whom she bore two sons, James George Benziger (1914–1995) and George Peter Joseph Adelrich Benziger (1917–1985). Catherine Ellen Brown (Helen) died in Jackson County, Illinois.

They raised three of their nieces: Grace, Florence, and Helen Tobin. There were other nieces and nephews who lived with the Browns occasionally.[2]: xxiv, 105

Separation

| External image | |

|---|---|

In 1909, Brown and his wife signed a separation agreement. The couple were both Catholic and they never divorced.[7] The agreement gave Margaret a cash settlement and possession of the Victorian mansion on Pennsylvania Street in Denver's wealthy Capital Hill neighborhood, and also the summer mansion Avoca Lodge in Southwest Denver, near Bear Creek. She also received a $700 monthly allowance (equivalent to $19,066 today) to continue her travels and philanthropic activities. Although they never reconciled, they remained connected and cared for each other throughout their lives. Margaret said of Brown "I've never met a finer, bigger, more worthwhile man than J.J. Brown."[2]: 217 [5]

Death

Brown died on September 5, 1922, in Hempstead, New York.[5][18] J.J. Brown left vast, yet complicated, real estate, mining, and stock holdings. It was unknown to the Browns and their lawyers how much was left in the estate. Prior to J.J.’s death, he had transferred a large amount of money to his children. Their children were also unaware how much money that Margaret had, but were displeased at the amount of money that she spent on charity. Margaret and her children fought in court for six years to settle the estate.[2]: 220–221

Margaret died on October 26, 1932. Both Brown and Margaret are buried in the Cemetery of the Holy Rood in Westbury, New York.[19][20]

Notes

- ↑ Secondary sources show his date of birth at September 27, 1854. In primary public records, his year of birth is generally 1854. His tombstone records his date of birth as September 27, 1855. His death certificate shows his date of birth as September 29, 1853.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Ferril, William Columbus (1911). Sketches of Colorado: In Four Volumes, Being an Analytical Summary and Biographical History of the State of Colorado. Western Press Bureau Company. p. 263.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Iversen, Kristen (1999). Molly Brown: Unraveling the Myth. Johnson Books. ISBN 978-1-5556-6237-0.

- 1 2 3 Mooney, Tom (April 22, 2012). "1940s Census brings regional hunters success". Times Leader. p. 12. Retrieved June 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Colorado Sugar Manufacturing Company" (PDF). Colorado Magazine. Vol. 55, no. 1. Winter 1978.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Malcomb, Andrea (Winter 2017). "James Joseph Brown" (PDF). Historic Denver Inc. p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 Andrea Malcomb (November 30, 2019). "J.J. and Leadville's Crystal Palace". Molly Brown House Museum. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Collection: Margaret "Molly" Tobin Brown Papers - Identifier WH53 - Microfilm Mflm175". Denver Public Library Archives, Western History and Genealogy. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Wommack, Linda (November 11, 2014). Historic Colorado Mansions & Castles. Arcadia Publishing. pp. PT57. ISBN 978-1-62585-286-1.

- ↑ "Lake County". coloradoencyclopedia.org. October 29, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ↑ "John F. Campion". National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Collection: John F. Campion papers, Biographical note". Rare and Distinctive Collections. University of Colorado Boulder Archives. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ↑ Downes, Brian (November 22, 1992). "Henry and 'Molly': Tales of the Denver Browns". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ↑ Fenelon, Marge (October 20, 2016). "The Unsinkable Molly Brown". National Catholic Register. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- 1 2 "J.J. Brown's victorian, wood mining table". History Colorado. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ↑ Harper, Kimberly. "Molly Brown (1867 - 1932)". Historic Missourians. State Historical Society of Missouri. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ↑ Hoffman, Shannon M. (December 6, 2017). "7 holiday-decorated Colorado spots worth the drive". The Denver Post. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ↑ "L.P. Brown Collection: Brown Family Papers" (PDF). History Colorado. January 6, 1976. pp. 6–7. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Pioneer Mine Man, Ibex Owner, Dies: James Joseph Brown". The San Francisco Examiner. September 7, 1922. p. 5. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Quiet Services Held for 'Unsinkable Mrs. Brown'". The San Bernardino County Sun. November 1, 1932. p. 2. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ "Mrs Margaret Brown (Molly Brown) (née Tobin)". Encyclopedia Titanica. Retrieved April 19, 2016.