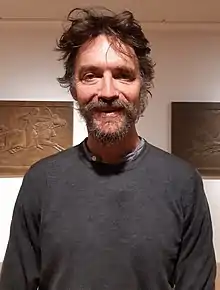

Professor Sir James Mallinson | |

|---|---|

at Khalili Lecture Theatre, SOAS | |

| Born | 22 April 1970 |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford |

| Occupation | Indology |

| Title | Boden Professor of Sanskrit at the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford |

| Website | http://www.khecari.com/index.html |

Sir James Mallinson, 5th Baronet, of Walthamstow (born 22 April 1970) is a British Indologist, writer and translator. He is recognised as one of the world's leading experts on the history of medieval Hatha yoga.[1]

Early life

Mallinson became interested in India by reading Rudyard Kipling's novel Kim as a teenager; the book describes an English boy travelling India with a holy man.[2] He was educated at Eton College and the University of Oxford, where he read Sanskrit and Old Iranian for his bachelor's degree, and studied the ethnography of South Asia for his master's degree at SOAS University of London.[3][4] Mallinson is described as "perhaps the only baronet to wear dreadlocks";[2] he let his hair grow out from 1988 on his first visit to India during his gap year.[2] He cut his hair in 2019 after the death of his guru, Mahant Balyogi Sri Ram Balak Das, who had initiated him into the Ramanandi Sampradaya at the Ujjain Kumbh Mela in 1992. Supervised by Alexis Sanderson, his doctoral thesis at Oxford was a critical edition and translation of the Khecarīvidyā with an explanation of its place in the Hatha Yoga traditions.[3]

Academic career

Mallinson is Boden Professor in Sanskrit at the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford.[5] He was previously Reader in Sanskrit and Yoga Studies at SOAS, University of London where he held the Sanskrit position since 2013. Prior to his appointment at SOAS, Mallinson worked as a principal translator for the Clay Sanskrit Library. He is the author of nine books, all of them translations and editions of Sanskrit texts on yoga, poetry, or epic tales.[3] Mallinson has written numerous book chapters and papers on the history of yoga, in particular the early development of physical or Hatha Yoga,[3] on which he is recognised as the world's leading expert.[1] In 2014 he received a European Research Council Consolidator Grant worth €1.85 million for a five-year six-person research project on the history of Hatha Yoga.[6] In 2018, he opened the SOAS Centre of Yoga Studies.[7]

Personal life

Mallinson travels to India each year, and has spent months at a time living as a Sadhu, taking only a blanket and a small bag.[2] He enjoys paragliding including in the Himalayas and has accordingly been nicknamed the "flying yogi", a humorous allusion to the yogic flying of Transcendental Meditation.[2] He has competed internationally for the British paragliding team and won the British Open paragliding competition in 2006.[8] In 2018 he became the first person to cross the eastern Solent on a paraglider.[9][10][11] He has two daughters with his wife Claudia.[12][8] In 2015, Mallinson appeared in the Smithsonian Channel documentary West Meets East with his longtime friend, the actor Dominic West, which was shown in the UK on BBC Four;[13] they visited the Kumbh Mela at Allahabad, where he was ordained as a Mahant (Abbot) of the Terah Bhai Tyagi suborder of the Ramanandi Sampradaya, the only Westerner to receive this honour.[12][2][14]

Works

Roots of Yoga

One of Mallinson's books, Roots of Yoga, with Mark Singleton as co-editor, is accessible to the public as well as to scholars. It contains a selection of texts on yoga from ancient times to the 19th century, presenting the core teachings.

Neil Sims, reviewing the book on the Indian Philosophy Blog, calls the book scholarly, writing that the editors "do an admirable job of letting the texts speak for themselves. No hint of partisanship, or even a preferred view, is given." In Mills's view, the book succeeds both on the level of increasing historical understanding among yoga students and teachers, and in contributing to yoga and South Asian scholarship.[15]

In a review in Yoga Journal, Matthew Remski points to the book's "endlessly diverse sources", which include "new critical translations of over 100 little-known yoga texts dating from 1000 BCE to the 19th century, threaded together with clear and steady-as-she-goes commentary". The translations, he states, "explode the available resources for everyday practitioners." Remski proposes that it may "become the top book on every yoga teacher training reading list in the English-speaking world."[16]

The researcher Adrian Munoz, reviewing the book in Estudios de Asia y África, notes that while it is principally a sourcebook of "innumerable" yoga manuscripts, mainly in Sanskrit, rather than the presentation of any particular thesis, it is accompanied by an erudite 30-page introduction that sets the documents in their historical context.[17]

The yoga teacher Richard Rosen writes that Roots of Yoga is appropriately in Penguin Classics as "this monumental anthology" of some 150 primary Sanskrit sources is destined to become a classic.[18]

The Indologist Alexis Sanderson writes that the anthology's "unprecedented array of sources [...] will be an indispensable companion for all interested in yoga, both scholars and practitioners".[19]

Major publications

- 2004. The Gheranda Samhita. New York: YogaVidya.com.

- 2005. "Rāmānandī Tyāgīs and Haṭhayoga," pp. 107–121 in the Journal of Vaishnava Studies Vol. 14, No. 1/Fall 2005. Reprinted in Namarupa magazine (2006).

- 2005. The Emperor of the Sorcerers by Budhasvamin. Vols. 1, 2. New York University Press.

- 2006. Messenger Poems by Kalidasa, Dhoyi & Rupa Gosvamin. New York University Press.

- 2007. The Shiva Samhita. New York: YogaVidya.com.

- 2007. The Khecarīvidyā of Ādinātha. A critical edition and annotated translation of an early text of haṭhayoga. London: Routledge.

- 2007, 2009 The Ocean of the Rivers of Story by Somadeva. Vols. 1, 2. New York University Press.

- 2011. "Siddhi and Mahāsiddhi in Early Haṭhayoga", pp. 327–344 in Yoga Powers, ed. Knut A. Jacobsen. Leiden: Brill.

- 2011. "The Original Gorakṣaśataka," pp. 257–272 in Yoga in Practice, ed. David Gordon White. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- 2011. "The Yogīs' Latest Trick". Review article in Tantric Studies (University of Hamburg).

- 2011. 10,000-word Entry on "The Nāth Saṃpradāya" in the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism Vol. 3 (pp. 407–428). Leiden: Brill.

- 2011. 5,000-word Entry on "Haṭha Yoga" in the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism Vol. 3 (pp. 770–781). Leiden: Brill.

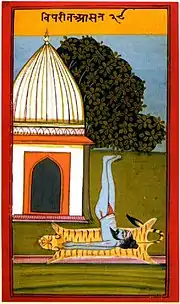

- 2013. "Āsana" (with Debra Diamond), pp. 150–159 in Yoga: The Art of Transformation, ed. Debra Diamond. Washington DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Smithsonian Institution).

- 2013. "Yogic Identities: Tradition and Transformation". Smithsonian Institution Research Online. This is an online-only publication and can be found here.

- 2013. "Yogis in Mughal India", pp. 35–46 in Yoga: The Art of Transformation, ed. Debra Diamond. Washington DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Smithsonian Institution).

- 2014. "Haṭhayoga's Philosophy: A Fortuitous Union of Non-Dualities", pp. 225–247 in Journal of Indian Philosophy, volume 42, issue 1.

- 2014. "The Yogīs' Latest Trick," pp. 165–180 in Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, volume 24, issue 1.

- 2014. Entry on "The Kumbh Mela" in Keywords in Modern Indian Studies. Oxford University Press (Delhi) in the series "SOAS Studies on South Asia".

- 2016. "Śāktism and Haṭhayoga." In: Goddess Traditions in Tantric Hinduism: History, Practice and Doctrine, edited by Bjarne Wernicke-Olesen. London: Routledge, 2016. pp. 109–140.

- 2017. Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. With Mark Singleton.

- 2022 The Amṛtasiddhi and Amṛtasiddhimüla. Institut Français de Pondichéry. With Péter-Dániel Szanto. Critical edition.

References

- 1 2 Shearer, Alistair (2020). The Story of Yoga: From Ancient India to the Modern West. Hurst. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-78738-192-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Interview with James Mallinson 'Sanskrit and paragliding'". Wild Yoga. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "James Mallinson". SOAS. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ↑ Dowling, Tim (9 September 2015). "West Meets East review: the jar of burning dung on the head adds new insight to the old celeb-travel show". The Guardian.

- ↑ "James Mallinson". www.ames.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ↑ "ERC Consolidator Grants 2015 results" (PDF). ERC. 10 March 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ↑ "James Mallinson opens the SOAS Centre of Yoga Studies". SOAS. SOAS. 8 May 2018. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- 1 2 Thomas, Priya (25 July 2012). "Do Yogis Still Fly? Fables and Flightpaths of the Itinerant Yogi: An Interview with Jim Mallinson PhD". Shivers up the spine.

- ↑ "Ozone Paragliders". Ozone Paragliders. 22 July 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ "Cross Country Magazine". 14 September 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ "Isle of Wight Country Press". 2 July 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- 1 2 Evans, Jules (27 January 2017). "James Mallinson, the sadhu-academic". Queen Mary University London. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ↑ "West Meets East". BBC Four. 8 September 2015.

- ↑ "The making of a mahant: a journey through the Kumbh Mela festival". Financial Times. 8 March 2013.

- ↑ Sims, Neil (30 December 2017). "Book Review of Roots of Yoga, Translated and Edited by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton". The Indian Philosophy Blog. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ Remski, Matthew (12 April 2017). "10 Things We Didn't Know About Yoga Until This New Must-Read Dropped". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ↑ Munoz, Adrian (2018). "James Mallinson y Mark Singleton (trad., ed. e introd.), Roots of Yoga, Londres, Penguin Books, 2017, 540 pp". Estudios de Asia y África (in Spanish). 53 (1): 230–232. doi:10.24201/eaa.v53i1.2337.

- ↑ Rosen, Richard. "The Roots of Yoga". You and the Mat. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ↑ "Roots of Yoga | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". Penguin Random House. Retrieved 21 May 2019.