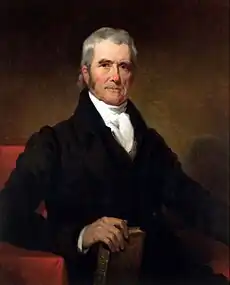

James Wayne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office January 14, 1835 – July 5, 1867 | |

| Nominated by | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | William Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Seat abolished |

| Chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee | |

| In office February 22, 1834 – January 13, 1835 | |

| Preceded by | William Archer |

| Succeeded by | John Mason |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's at-large district | |

| In office March 4, 1829 – January 13, 1835 | |

| Preceded by | George Gilmer |

| Succeeded by | Jabez Jackson |

| 16th Mayor of Savannah, Georgia | |

| In office September 8, 1817 – July 12, 1819 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Charlton |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Charlton |

| Member of the Georgia House of Representatives | |

| In office 1815–1816 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1790 Savannah, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | July 5, 1867 (aged 76–77) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Other political affiliations | Jacksonian |

| Spouse |

Mary Johnson (m. 1813) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Princeton University (BA) |

James Moore Wayne (1790 – July 5, 1867) was an American attorney, judge and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1835 to 1867. He previously served as the 16th Mayor of Savannah, Georgia from 1817 to 1819 and the member of the United States House of Representatives for Georgia's at-large congressional district from 1829 to 1835, when he was appointed to the Supreme Court by President Andrew Jackson. He was a member of the Democratic Party.

Early life

Wayne was born in Savannah, Georgia in 1790. He was the son of Richard Wayne, who came to America in 1760, and married Elizabeth (née Clifford) Wayne on September 14, 1769.[1] James' mother died in 1804 when James was fourteen years old. His sister Mary Wayne, wife of Richard Stites, was the great-grandmother of Juliette Gordon Low, the founder of the Girl Scouts of the USA.[2]

After completing preparatory studies, Wayne attended The College of New Jersey (today known as Princeton University), where he graduated in 1808.[3] After Princeton, he read law to be admitted to the bar in 1810, and began his practice in Savannah.[4]

Career

From 1812 to 1815, during the War of 1812, he served in the United States Army as an officer in the Georgia Hussars. He served in the Georgia House of Representatives from 1815 to 1816. He then served as Mayor of Savannah from 1817 to 1819, thereafter returning to private practice in Savannah until 1824.[5]

He then served as a judge, first of the Court of Common Pleas in Savannah, Georgia from 1819 to 1824, and then of the Superior Court of Georgia from 1824 to 1829, until he was elected as a Jacksonian to the United States House of Representatives, serving from March 4, 1829, to January 13, 1835.[4]

He resigned his seat in the House to accept the appointment as an associate justice to the Supreme Court. He was nominated by President Andrew Jackson on January 7, 1835, to a seat vacated by William Johnson, and was confirmed by the United States Senate on January 14, 1835, receiving his commission the same day. He served on the court until his death on July 5, 1867. He favored free trade, opposed internal improvements by Congress (except of rivers and harbors), and opposed the rechartering of the United States Bank.[6]

U.S. Supreme Court

While Wayne served his time as an associate justice he heard many cases about slavery, tax, and reform. A "Jacksonian", Wayne agreed with President Jackson on the ideals of deepening rivers and harbors, but disagreed on the expansions of highways and canals. Wayne also agreed with Jackson on the Indian Removal Act and believed that the land that used to belong to the Indians would belong to the state. The fact that Wayne refused to accept the Indians as an independent nation and forced them to move west, made him appealing to Georgians. Wayne was a Southern Unionist, and against the formation of the Confederate States of America, which was shocking because he was from the state of Georgia. As a Unionist in a southern state, Wayne took a careful approach on the ideals of nullification and consolidation.

While Justice Wayne himself remained loyal to the Union, his son Henry C. Wayne served as a general in the Confederate Army.

Louisville, Cincinnati & Charleston Railroad Co. v. Letson

In 1844, Justice Wayne heard the case Louisville, Cincinnati & Charleston Railroad Co. v. Letson.[7] This case was about a man named Letson who brought a contract against a railroad company, claiming that the cities did not fulfill the contract with him for the expansion of the road. It centered on the principle that a citizen in a particular state should have the right to sue a corporation, which is based in another state and even conducts its business in another state. Justice Wayne opened his statement regarding the case when he said, "The jurisdiction of the court is denied in this case upon the grounds that two members of the corporation sued are citizens of North Carolina; that the state of South Carolina is also a member, and that two other corporations in South Carolina are members, having in them members who are citizens of the same state with the defendant in error" (43 U.S. 497, 555). Later in his statement, Justice Wayne commented, "A corporation created by a state to perform its functions under the authority of that state and only suable there, though it may have members out of the state, seems to us to be a person, though an artificial one, inhabiting and belonging to that state, and therefore entitled, for the purpose of suing and being sued, to be deemed a citizen of that state" (43 U.S. 497, 555). In these statements, Justice Wayne was explaining how owners stopped being relevant and that businesses now had easy accessibility to federal courts. This case was instrumental as it showed the view of the Supreme Court that corporations could be viewed as 'citizens' of the states where they were incorporated. This court case was significant in Justice Wayne's career and development because it showed that he was willing to increase dominion in the courts.

Dred Scott v. Sandford

The court case of Dred Scott v. Sandford was argued in front of the United States Supreme Court, and was decided for Sanford by a 7–2 vote on March 6, 1857, with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney giving the majority opinion and Judge Wayne concurring. This landmark decision against slave Dred Scott ruled that African-Americans, whether slave or free, were not to be considered American citizens and thus could not sue in federal court. The ruling also found the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, ruling that it violated the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and that, therefore, the federal government had no jurisdiction to regulate slavery on federal property. Though the Court thought this ruling would put to rest the question of slavery, it exacerbated tensions and led directly to the American Civil War, which resulted in the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1865) abolishing slavery, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, and the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1868), granting equal citizenship to African-Americans.

In Dred Scott v. Sandford, Taney wrote that the Constitution viewed people of African American descent as an "inferior order and altogether unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect" (60 U.S. 393). The vast majority of scholars and historians[8] view this decision, which Justice Wayne concurred with, as one of the worst to ever be handed down by the Court. Justice Wayne showed his concurrence with Taney when he wrote: "Concurring as I do entirely in the opinion of the court as it has been written and read by the Chief Justice" (60 U.S. 393), he went on to write that he concurred in "assuming that the Circuit Court had jurisdiction," but he abstained from expressing any opinion upon the eighth section of the act of 1820, known commonly as the Missouri Compromise law, and "six of us declare that it was unconstitutional" (60 U.S. 393).

Judicial views

Justice Wayne served on the Supreme Court for 32 years, one of the longest terms for any justice. His leanings stayed consistent and many of his decisions believed power resides in the federal offices such as the U.S. Congress. He held to this in the Dred Scott case, supporting Chief Justice Taney's opinion in the face of harsh criticism by many. With the beginning of the Civil War, Wayne was thrust into personal and professional crisis. He chose to remain with the Court while his own son left the U.S. Army to fight as a general in the Confederate Army. Another one of his colleagues, John Campbell, also left the Court to serve in the Confederacy. However, Wayne held to his nationalistic views, although it made him unpopular in his home state of Georgia, believing there was no legal support for a state to secede. He also felt that by remaining on the Court he could continue to support Southern causes. After the war ended, he never forgot his Southern roots and labored hard to protect the South from penalties.

As of the time of his death in 1867, Wayne was the last veteran of the Marshall Court remaining on the bench.

In order to prevent President Andrew Johnson from appointing any justices, Congress passed the Judicial Circuits Act in 1866, eliminating three of the 10 seats from the Supreme Court as they became vacant, with the intent of eventually reducing the size of the Court to seven justices. The vacancy caused by the death of Justice John Catron in 1865 had not been filled, so, upon Wayne's death, there were eight justices on the Court. In 1869 Congress passed the Circuit Judges Act, setting the size of the Court at nine members. The Court still had eight justices at the time of this Act, so one new seat was created, which was ultimately filled on March 21, 1870, by Joseph Philo Bradley (in the meantime, William Strong had filled the seat vacated by Robert Cooper Grier).[2]

Personal life

On March 4, 1813, Wayne was married to Mary Johnson Campbell (1794–1889).[3] Mary was the daughter of Alexander Campbell (a grandson of the Scottish-born Rev. Archibald Maciver Campbell) and Mehitable Hetty (née Hylton) Campbell.[9] Together, Mary and James were the parents of two surviving children:

- Henry Constantine Wayne (1815–1883), who married Mary Louisa Nicoll (1821–1873), a daughter of Henry Woodhull Nicoll, in 1842. Mary's older sister, Elizabeth Smith Nicoll, was the wife of Gen. Alexander Hamilton, oldest grandson of Alexander Hamilton.[10]

- Mary Campbell Wayne (1818–1885), who married Dr. Brig.-Gen. John Meck Cuyler on October 15, 1840. Mary and John were the grandparents of Mary "May" Caroline Campbell Cuyler, who married Sir Philip Grey Egerton, 12th Baronet in 1893.[11]

From 1818 to 1821, he built a Regency style home in Savannah. In 1831, he sold his home to his niece, Sarah Anderson (née Stites) Gordon and her husband, William Washington Gordon, who studied law under Wayne and later served as the mayor of Savannah. Sarah and William were Juliette's grandparents.[12] Today, the home is called the Juliette Gordon Low Birthplace.[12]

Wayne died on July 5, 1867, in Washington, D.C., and was interred in Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, Georgia.[4]

Legacy and honors

During World War II the Liberty ship SS James M. Wayne was built in Brunswick, Georgia, and named in his honor.[13]

The Georgia Historical Society holds a collection of James Moore Wayne's papers. The collection is available for research and contains correspondence and miscellaneous papers, dating 1848 to 1863. Wayne was President of the Georgia Historical Society from 1841 to 1854, and then again from 1856 to 1862.

See also

References

- ↑ Biskupic, Joan; Witt, Elder (1997). Guide to the U.S. Supreme Court. Congressional Quarterly. p. 879. ISBN 9781568022376. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- 1 2 Hall, Timothy L. (2001). Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. Infobase Publishing. pp. 86–89. ISBN 9781438108179. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- 1 2 Looney, J. Jefferson; Woodward, Ruth L. (2014). Princetonians, 1791-1794: A Biographical Dictionary. Princeton University Press. pp. 121, 414, 416, 417. ISBN 9781400861279. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 "WAYNE, James Moore - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ↑ Lawrence, Alexander A. James Moore Wayne, Southern Unionist. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1943.

- ↑ New International Encyclopedia

- ↑ "Louisville, Cincinnati & Charleston R. Co. V. Letson, 43 U.S. 497 (1844)". Archived from the original on 2017-03-22. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ↑ "13 Worst Supreme Court Decisions of All Time". 14 October 2015. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ↑ Maciver, Evander (1905). Memoirs of a Highland Gentleman: Being the Reminiscences of Evander Maciver of Scourie. T. and A. Constable. p. 260. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ↑ Woodhull Genealogy: The Woodhull Family in England and America. H.T. Coates. 1904. p. 99. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ↑ Nicoll, Maud Churchill (1912). The Earliest Cuylers in Holland and America and Some of Their Descendants: Researches Establishing a Line from Tydeman Cuyler of Hasselt, 1456. T.A. Wright, Printer and Publisher. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- 1 2 "The Life of William W. Gordon I, May 26, 1989" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2008. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ↑ Williams, Greg H. (25 July 2014). The Liberty Ships of World War II: A Record of the 2,710 Vessels and Their Builders, Operators and Namesakes, with a History of the Jeremiah O'Brien. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476617541. Archived from the original on 14 October 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

Further reading

- McMahon, Joel. Our Good and Faithful Servant: James Moore Wayne and Georgia Unionism Mercer University Press, 2017. x, 249 pp.

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at Google Books.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- White, G. Edward. The Marshall Court & Cultural Change, 1815-35 (1991).