Brien McMahon | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) McMahon in 1945 | |

| Chair of the Joint Atomic Energy Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1949 – July 28, 1952 | |

| Preceded by | Bourke B. Hickenlooper |

| Succeeded by | Carl T. Durham (Acting) |

| In office August 1, 1946 – January 3, 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Himself (Senate Atomic Energy Committee) |

| Succeeded by | Bourke B. Hickenlooper |

| Chair of the Senate Atomic Energy Committee | |

| In office October 22, 1945 – August 1, 1946 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Himself (Joint Atomic Energy Committee) |

| Secretary of the Senate Democratic Caucus | |

| In office January 3, 1945 – July 28, 1952 | |

| Leader | Alben W. Barkley Scott W. Lucas Ernest McFarland |

| Preceded by | Francis T. Maloney |

| Succeeded by | Thomas C. Hennings Jr. |

| United States Senator from Connecticut | |

| In office January 3, 1945 – July 28, 1952 | |

| Preceded by | John A. Danaher |

| Succeeded by | William A. Purtell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | James O'Brien McMahon October 6, 1903 Norwalk, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | July 28, 1952 (aged 48) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Education | Fordham University (BA) Yale University (LLB) |

| Signature |  |

Brien McMahon (born James O'Brien McMahon) (October 6, 1903 – July 28, 1952) was an American lawyer and politician who served in the United States Senate (as a Democrat from Connecticut) from 1945 to 1952. McMahon was a major figure in the establishment of the Atomic Energy Commission, through his authorship of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (the McMahon Act).

McMahon served as chairman of the Senate Special Committee on Atomic Energy, and the first chairman of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy. McMahon was a key figure in the early years of atomic weapons development and an advocate for the civilian (rather than military) control of nuclear development in the USA. Also, in 1952, McMahon proposed an "army" of young Americans to act as "missionaries of democracy", which sowed the seeds for what later became the Peace Corps.

Early life and education

McMahon was born in 1903 in Norwalk, Connecticut.[1] McMahon graduated Fordham University in 1924 and then Yale Law School in 1927.[1] McMahon changed his name to Brien McMahon the same year as being admitted to the bar.

Justice career

McMahon began a practice in Norwalk and later served as a judge on that town's city court,[1] appointed to the position by Connecticut Governor Wilbur L. Cross.[2] However, McMahon quickly resigned to become special assistant to the Attorney General of the United States in 1933. Attorney General Homer Cummings was also from Connecticut. In 1935, McMahon was appointed as United States Assistant Attorney General overseeing the Department of Justice's Criminal Division.[1]

Among prominent cases associated with McMahon in the Criminal Division were the prosecutions of John Dillinger's lawyer, Louis Piquette (for harboring a criminal) and the trials of gangsters associated with 'Baby Face' Nelson.

However, the case that elevated McMahon to national renown and laid the foundation for his political career was the Harlan County Coal Miners' case. It was the first attempt to enforce the Wagner Act protecting unions. The case became famous, less for legal principles than for the violence and scandal surrounding the trial.

Although he lost, he "received wide public recognition and a reputation as a courageous and honest upholder of justice, both of which would further his political ambitions," according to a biography accompanying the introduction to his papers, held by the Georgetown University Library.[2]

In 1939, McMahon left government service and resumed his law practice. In February 1940 McMahon married Rosemary Turner (June 21, 1917 – October 11, 1986), and they had a daughter, Patricia. Rosemary was the half-sister of the British politician and best-selling novelist (Lord) Jeffrey Archer (1940– ).

Congressional career

McMahon mounted a successful campaign for a Connecticut United States Senate seat in 1944, defeating incumbent John A. Danaher, with internationalism (McMahon) vs. isolationism (Danaher) a major point of debate.[2]

On July 16, 1945, an atomic bomb was successfully detonated at Alamogordo, New Mexico, after which Senator Brien McMahon of Connecticut called it "the most important thing in history since the birth of Jesus Christ." In late 1945, McMahon was appointed Chairman of the Senate Special Committee on Atomic Energy, which explored legislative alternatives to the War Department sponsored May-Johnson bill. McMahon lacked knowledge about atomic energy, but saw the chairmanship as a means to assert himself as a new Senator, especially as the May-Johnson bill underwent increased attack from scientists and later lost support of the Truman White House.

On December 20, 1945, Brien McMahon introduced into the Senate legislation for an alternative atomic energy bill, which was quickly known as the McMahon Bill. The liberal bill placed control of atomic research in the hands of scientists and was broadly supported by scientists. McMahon himself framed the controversy as a question of military versus civilian control of atomic energy, even though the War Department bill was primarily a civilian bill as well. McMahon's Special Committee on Atomic Energy held many hearings during late 1945 and early 1946, thereby airing arguments about domestic postwar legislation for controlling atomic energy. In the spring of 1946, the McMahon Bill underwent major revisions in order to appease conservative elements in the Senate. The resulting bill passed the Senate and the House. On August 1, 1946, President Harry Truman signed the McMahon Bill into law as the Atomic Energy Act of 1946.[3]

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 created a special Congressional committee, the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy. Brien McMahon served as its first chairman in 1946, and again in 1949–1952.[4] McMahon hired as the committee's executive staff director William L. Borden, who would play an influential role on the committee (and after McMahon's death, in the Oppenheimer security hearing).[5]

The first atomic bomb test by the Soviet Union in August 1949 came earlier than expected by Americans, and McMahon immediately urged that U.S. production of atomic weapons be substantially increased.[4] Moreover, during the next several months there was an intense debate within the U.S. government, military, and scientific communities regarding whether to proceed with development of the far more powerful hydrogen bomb, then known as "the Super".[4] McMahon was strongly in favor of going ahead with the Super, and argued as much in a series of letters he wrote to President Truman.[5] The senator rejected morality-based arguments against the hydrogen bomb based on it being inherently more destructive than previous weapons, asking "Where is the valid ethical distinction between" the World War II multi-day-and-night bombing of Hamburg, the firebombing of Tokyo, and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and any future raid with whatever technology that caused mass casualties.[4]

Connecticut voters reelected McMahon to his Senate seat in 1950. During his entire tenure in the Senate, he served as Secretary of the Senate Democratic Conference.

Presidential campaign, illness and death

Beginning in January 1952, McMahon was mentioned as a possible candidate in the 1952 Democratic Party presidential primaries, but he vacillated over whether he was actually running or not.[1] His campaign slogan was to be, "The Man is McMahon", and his main campaign platform was the ensuring of global peace through strength of atomic weaponry.[2] Then in March 1952 he fell ill and spent a week at Bethesda Naval Hospital; his condition would be determined to be lung cancer.[1] From his sickbed, he sent a message to the Democratic state convention in Hartford, Connecticut saying that if elected president, he would tell the Atomic Energy Commission to manufacture thousands of hydrogen bombs.[6] By the time of the 1952 Democratic National Convention in July, he was too weak to be considered an actual candidate, but the delegation from Connecticut initially cast their 16 votes for him as a symbolic gesture.[1]

Brien McMahon served in the United States Senate until his death at Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., on July 28, 1952, at age 48.[1] His obituary was given front page, above the fold treatment in The New York Times.[1] More than four years remained in his second Senate term.

Brien McMahon is buried in St. Mary's Cemetery in Norwalk.

Legacy and honors

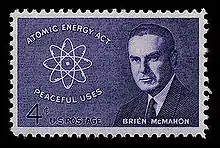

A commemorative stamp honoring Brien McMahon and his role in opening the way to peaceful uses of atomic energy was issued by the United States on July 28, 1962, at Norwalk, Connecticut. The stamp features a portrait of McMahon facing a rendition of an atomic symbol.

Brien McMahon High School, in Norwalk, is named after him. Brien McMahon Hall, a residence hall at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, also bears his name.

Footage of McMahon is included in the 1982 documentary The Atomic Cafe giving a speech urging a reasoned response to the acquisition of atomic weapons contrasting with the more McCarthyite speeches of Republican Senators Owen Brewster, Richard Nixon and Democratic Representative Lloyd Bentsen.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Senator McMahon Dies at 48; Leader in Atomic Progress". The New York Times. July 29, 1952. pp. 1, 9.

- 1 2 3 4 The Brien McMahon Papers Archived 2010-06-29 at the Wayback Machine Biography/Introduction to papers. Georgetown University library. Retrieved 2-7-09.

- ↑ Richard G. Hewlett and Oscar Anderson, Jr., The New World (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1962), chapters 13-14.

- 1 2 3 4 Young, Ken; Schilling, Warner R. (2019). Super Bomb: Organizational Conflict and the Development of the Hydrogen Bomb. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 1, 4, 33–34, 77.

- 1 2 Bundy, McGeorge (1988). Danger and Survival: Choices About the Bomb in the First Fifty Years. New York: Random House. pp. 204–205, 211, 305.

- ↑ Richard G. Hewlett and Francis Duncan, Atomic Shield (U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 1969), 585.

- American National Biography; Dictionary of American Biography; U.S. Congress.

- Memorial Services. 83d Cong., 1st sess., 1953. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1953.