| جمعية خير | |

Jamiat kheir School | |

Zone of influence | |

| Formation | 1901 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Aḥmad Basandiet Muḥammad bin ʻAbdullah Shahāb Muḥammad al-Fakhir bin ʻAbdurrahman al-Mashhoor Idrus bin Aḥmad Shahāb |

| Type | Foundation |

| Purpose | Religious islamic; Education |

| Headquarters | Jakarta, Indonesia |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 6°11′26″S 106°48′55″E / 6.190668°S 106.815351°E |

Region served | Indonesia |

| Website | jamiatkheir |

Jamiat Kheir (Jam'iyyatou Khair; Arabic: جمعية خير; Arabic pronunciation: [dʒamʕijjatu xair]; different Latin spellings have also been used in the past, such as Djamiat Chair, Djameat Geir, Djamijat Chaer, Jam'iyyat khair or Jamiatul Khair) is one of a few early private institutions in Indonesia that is engaged in education, and is instrumental in the history of Indonesian struggle against Dutch colonialism, preceding Sarekat Islam and Budi Utomo. It is headquartered in Tanah Abang, Central Jakarta.

History

The history of Jamiat Kheir can be divided into two periods, where during the first period (1905 - 1919) it was as a social organization (and included a school program), and the second period (since 1919) it becomes an education institution only.

Starting in 1898, several leaders of Arab community agreed to make an organization that aims to help social condition of the Arabs in Dutch East Indies. The Arab community leaders held meetings to realize their goals to help social life of the Muslim community and Arabs in Indonesia, and to prepare a plan to erect a modern Muslim education institution, as a response against the Dutch Indies education policy. The ideals were also in line with the idea of mufti of Betawi al-Sharif Habib ʻUthman ibn ʻAbdullah ibn Yaḥya, where he encouraged Muslims to build a religious institution to counteract the Christianization through public schools.[1] As a starting, In 1901 several prominent Arab community leaders in Batavia had an initiative to establish an organization that works in the field of social and Islamic education called Arabic: الجمعية الخيريه, romanized: Al-Jam'iyyatoul Khairiyah ("The Association of Goodness").[2]

The first location where it was founded was at Raudah Mosque on Pekojan Road II, seven years before the Budi Utomo. Near Pekojan Rd. II there is another mosque named Zawiyah Mosque, built by Habib Aḥmad bin Hamzah Alatas, who was born in Tarim, Hadhramaut. While still teaching at the mosque he used the yellow book Fath Mu'in, which until now still being used as a reference in many places. In front of the mosque there was another mosque called Masjid Nawir which was the largest mosque in West Jakarta. The mosque was built in 1760 and at the front there was a bridge called Jembatan Kambing which had been used by merchants for four generations. The name of the organization was al-Jam'iyyatoul Khairiyyah.

A petition was submitted to the government on August 15, 1903, to get official permission for the organization with the goals to provide assistance to the Arabs who were grieving or in loss of family member, and to assist funeral or wedding. The board members were Aḥmad Basandiet (chairman), Muḥammad bin ʻAbdullah Shahāb (vice chairman), Muḥammad al-Fakhir bin ʻAbdurrahman al-Mashhoor (secretary), Idrus bin Aḥmad Shahāb (as the treasurer) and in the later time involving ʻAli bin Aḥmad Shahāb (brother of Idrus).[1][2]

The request was not immediately granted by the Dutch government. The submission of the petition probably raised suspicions in the government, where it did not like any establishment of an association that engages in social movements. The Dutch East Indies government then took some actions against the newly founded Jamiat Kheir, of which it limited the areas that could be visited by the Arabs and Arab descendants in Indonesia. In Batavia, the Dutch East Indies government determined the location of their gathering in Pekojan.[1]

The permit took two years to be granted by the government, where it then was issued in 1905, after Muḥammad bin ʻAbdurrahman al-Mash-hoor as the secretary of Jamiat Kheir sent a letter clarifying the intent and purpose of the establishment of the association on March 16, 1905.[1] On June 17, 1905, Jamiat Kheir as an organization was officially authorized by the Governor General of the Dutch East Indies and its Articles of association were also approved. However, Jamiat Kheir was forbidden to establish branches outside Batavia. Jamiat Kheir was used as a social gathering for all the aspirations of the Alawiyyin, non-Sayyid and Ajami.[3]

The official license issued by the Dutch government was based on the input from Priesterraden, a special body set up in 1882 with the task of overseeing religious and Islamic education. On the advice of this body in 1905, the government passed a law requiring any instructor must first get permission to teach. At that time the government had already feared of possible resurgence among indigenous people. Soon after the permission was obtained, the Jamiat Kheir opened an elementary level (Ibtidaiyyah) madrasa in Pekojan which provided free education, using a curriculum blend of religious studies and general subjects. To show its anti-colonialism, non-religious subjects at the Jamiat Kheir were not taught in Dutch, but in English.[1]

The purpose of Jamiat Kheir as contained in the Articles of Association dated August 15, 1903 was to provide assistance to the Arabs, men and women living in and around Batavia, to ease their grief and loss of family member and to give assistance to hold a wedding. The first management of the organization consists of: Said bin Aḥmad Basandiet (chairman), Muḥammad bin ʻAbdullah Shahāb (Vice Chairman), Muḥammad al-Fakhir bin ʻAbdurrahman al-Mashhoor (Secretary), and Idrus bin Aḥmad Shahāb (Treasurer).

After gaining recognition as a legal entity, in accordance with article 10 of the Articles of Association dated August 15, 1903, the first general meeting of members was held on April 9, 1906. In addition to the election of the new management of the Jamiat Kheir consisting of Idrus bin ʻAbdullah al-Mashhoor (as chairman), Salim bin Awad Balweel (vice chairman), Muḥammad al-Fakhir bin ʻAbdurrahman al-Mashhoor (secretary) and Idrus bin Aḥmad Shahāb (treasurer), they also amended the Article. The new Articles of Association in the organization had the goals changed. In addition to provide assistance to members of society in the case of death or funeral and marriage problems (chapter 1), the Articles of Association contained a goal to set up schools through the implementation of teaching (chapter 2), and not only for Arabs, but to extend to other ethnicities, as long as he or she is a Muslim (chapter 4). The addition of the Statutes was approved by the government through the governor general's decision on October 24, 1906, because the Jamiat Kheir's Statutes did not contain political purposes and did not contain any incitement (which may endanger the national security of the Dutch Indies government). ʻAbdullah bin ʻAlwi Alatas as the leader of the Pan-Islamic movement gave his support for the establishment of this organization.

On 30 September 1907, in accordance with the decision of the general meeting of members, the board held an amendment again, and after the meeting on 27 April 1907 a new board was elected. In this year, Hajj Muḥammad Mansyur started teaching at the Jamiat Kheir school. He was chosen because of his ability to teach in the Malay language as well as his knowledge of Islamic sciences. Muḥammad Mansyur was also an advocate of Indonesian Independence of colonialism. He called for the Indonesians to fly the national flag, and for unity with the famous slogan rempuk which means deliberation. He was also one of the most knowledgeable scholars in astronomy at the time.[1]

Under the new stewardship consisting of Abūbakar bin ʻAli Shahāb as chairman and Muḥammad bin ʻAbdurrahman al-Mash-hoor as secretary, the board applied to change the Statute on January 31, 1908. The request was approved by the government on 29 June 1908.[1]

Jamiat Kheir advanced quite rapidly and its existence was spread quickly so that many cities and towns asked Jamiat Kheir to build its branch in their areas, but because of the prohibition not to set up branches outside of Batavia, the Jamiat Kheir urged them to set up their own associations. They ended up using the name 'Kheir' (Goodness) in their organization's last name, for example, the Madrasah al-Khairiyah established in Bantam, Banyuwangi and Teluk Betung. In addition, the number of members of the Jamiat Kheir also increased, among them are imams of the mosque, teachers, employees, village headmen or others.

In 1908, the Jamiat Kheir began a relationship with Islamic leaders in the Middle East, such as Yusuf ʻAli sharif a publisher of the newspaper al-Muayyad, editor-in-chief Kamil ʻAli for newspaper al-Liwa, ʻAbdul Ḥamid Zaki as publisher of the newspaper al-Siyasah al-Musyawarah, Aḥmad Hasan Ṭabarah a publisher of the newspaper Samarāt al-Funun Beirut, Muḥammad Said al-Majzub as publisher of the newspaper al-Qistah al-Mustaqim, ʻAbdullah Qāsim as editor-in-chief of the newspaper Shamsu al-Haqiqah, and Muḥammad Bāqir Beik as editor-in-chief of the newspaper al-ʻAdl.

On June 22, 1910, based on the April 1910 members' meeting several months earlier, the board proposed an amendment for a third time. Petition letters filed by Muḥammad ibn ʻAbdurrahman Shahāb as chairman and son of Shaikh Muḥammad ibn Shahāb as secretary and the changes were approved on October 3, 1910. The purpose of the Jamiat Kheir increasingly widespread, including:

- to establish and maintain school buildings and other buildings in Batavia for the benefit of Muslims,

- to improve the knowledge quality of pupils in Islamic sciences.

- to push Islamic studies to be taught at other schools

- to set up libraries and to collect books to increase knowledge and intelligence

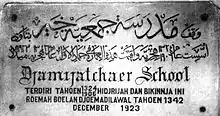

Eventually in 1918 the government decided that the Jamiat Kheir as an organization founded by Asian foreigners was prohibited from engaging in activities with ingenous people. They also emphasized that the Jamiat Kheir's permit could be revoked at any time. Being aware of government suspicion and its suppressions, Jamiat Kheir then took a strategy to change its Article of association again, especially in matters of education. Because Jamiat Kheir as a social organization had been suspected by the government due to its political activities, then on October 17, 1919, it amended its Article of association and became an education foundation. On the date, Jamiat Kheir became the Education Foundation of Jamiat Kheir based on the new dated October 17, 1919 which was recorded in the notary deed number 143, STICHTINGSBRIEF de STICHTING "SCHOOL DJAMEAT GEIR" (The Deed of Djameat Geir School), by Jan Willem Roeloffs Valk[4] in Batavia. The composition of the school board were Said Aboebakar bin Alie bin Shahab as The chairman of the board, Said Abdulla bin Hoesin Alaijdroes, Said Aloei bin Abdulrachman Alhabsi, Said Aboebakar bin Mohamad Alhabsi, Said Aboebakar bin Abdullah Alatas, Said Aijdroes bin Achmad bin Shahab and Sech Achmad bin Abdulla Basalama were the members of the board (the names are spelled as they were in the deeds). Two of the members were also the founders of Jamiat Kheir organization (the first period). Since then all activities of Jamiat Kheir conducted through its Education Foundation.[1] The school name is also slightly different from the original name of the organization (al-Jam'iyyatoul Khairiyyah).

On December 27, 1928, the Dutch Indies government granted first permission to found al-Rabiṭah al-ʻAlawiyah with the second permission issued on 27 November 1929, where many of the management members were also members of Jamiat Kheir. On August 12, 1931, at Karet St. no. 47, the Dārul Aytam (literally means House of orphans) orphanage was established by notarial deed of Dirk Johannes Michiel de Hondt (1886-1945)[5] No. 40, with its first chief Sayyid Abūbakar bin Muḥammad bin ʻAbdurrahman Al Habshī. It is located in Tanah Abang.[1]

Prominent members

Activity

Economy

On January 26, 1913, members of the Jamiat Kheir founded the printing company NV Handel-Maatschappij Setija Oesaha. The limited liability business Setija Oesaha was established and headquartered in Pabean sub-district, Pesayangan in Surabaya and the operation was entrusted to HOS Tjokroaminoto who served as the director. On March 31, 1913, the company published the newspaper Oetoesan Hindia, with Tjokroaminoto as its editor-in-chief.

Social

The activities of the Jamiat Kheir in the beginning were more directed towards social problems of community, concerning with the problems of poverty, illiteracy and ignorance suffered by Muslims as results of colonization. Initially, giving assistance to grieving family whose loss its family member, to help the funeral, to help orphans and aging elderly were major activities and programs of Jamiat Kheir. Later time, it built the orphanage Dārul Aytam which is dedicated to treating and educating orphans in Tanah Abang, Central Jakarta, which until now is still active.

The Jamiat Kheir also had an international reputation through the relationship with the Muslims in the middle east. On the basis of Islamic brotherhood, Jamiat Kheir helped financially to victims of the war in Tripoli, and built the Hejaz Railway connecting the city of Medina with the areas around the strip of Sham and others.

Politics

In politics, the Jamiat Kheir was involved in Sarekat Islam organization activities. Political activities of the Jamiat Kheir could be seen in its relationship with other Islamic states. This relationship also showed the attitude of Indonesians toward Dutch Indies government in general and showed the attitude of Jamiat Kheir in particular, which was not in line with the Dutch government.

Since 1902, Jamiat Kheir had published articles in some Egyptian newspapers which were submitted by Hasan bin ʻAbdullah bin ʻAlwi Shahāb. Another staff of Jamiat Kheir who was a correspondent for the newspaper al-Muayyad and Thamarāt al-Funnun, ʻAli bin Aḥmad bin Muḥammad Shahāb, since 1912 began sending his writings and published on various newspapers and magazines in Egypt and Turkey. These writings were essentially about issues around Dutch colonialism in Indonesia or British ruling in Malaysia. They revealed the evils of government rules that suppressed the people of the countries.[1]

Besides the two men, since 1908 Jamiat Kheir members also wrote about Islamic movements in Indonesia, about what they perceived as the Dutch East Indies government repression against the Muslim population of Indonesia. These writings were published on newspapers and magazines in Istanbul, Syria and Egypt, including the al-Manār magazine. Since the Jamiat Kheir's publications were distributed widespread, news about intimidations carried out by the Dutch government heard internationally and got enough attention. One of them was from Ottoman empire in Turkey which sent two envoys to Batavia, ʻAbdul ʻAziz al-Musawi and Galib Beik. The purpose of their visit stated to investigate the situation of Muslims in Indonesia. This investigation effort could be, to some extent, was influenced by the news sent by Jamiat Kheir members to Ottoman empire. However, both consuls received pressure and intimidation from the Dutch Government. The pressure and intimidation from the Dutch East Indies to the Jamiat Kheir instead created stronger ties of brotherhood between Arabs and indigenous Indonesian society. This made the Dutch East Indies government became increasingly fearful and anxious, especially when the Jamiat Kheir became a liaison between the Indonesian people and the Ottoman government which was very sympathetic to the struggle for independence in Indonesia.[1]

To complement the nationalism of Jamiat Kheir, the Regent of Serang whose also a member of the organization Jamiat Kheir, Aḥmad Djajadiningrat, built a competing organization that was also based in Batavia. The organization must be led by Indonesian noblemen to imitate the Jamiat Kheir whose many of the indigenous students were aristocratic Javanese, such as Ahmad Dahlan who later became the founder of Muhammadiyah. This was in line with Agus Salim's prediction stating that many members of the Budi Utomo would be former members of the Jamiat Kheir.[6] The name of the new organization, according to Aḥmad Djajadiningrat, should be similar to 'Jamiat Kheir', so they named it Budi Utomo. This name is the translated word of the Arabic Jamiat Kheir to Javanese, where the meaning of both words is very similar (benevolent society).[6]

Robert Van Niel in his book The Emergence of the Modern Indonesian Elite wrote that many members of the Sarekat Islam were former members of the Jamiat Kheir. Although, as stated in the Budi Utomo's resolution in 1911, a decision was made to no longer accept non-native Indonesians as members, many Arabs remained members of or actively collaborated with Sarekat Islam. In Batavia, the overwhelming number of registrations from people to become members of Sarekat Islam made the Sarekat Islam in March 1913 decided to stop admitting new members. The intention was to avoid the administration become chaotic and out of control.[6]

Education

The first board of Jamiat Kheir as an education foundation initially consists of (all names spelled as they are originally written in the Van Ophuijsen spelling, e.g., Said instead of Sayyid or Syed, Aboebakar instead of Abubakar, Moehamad instead of Muhammad):

- Said Aboebakar bin Mohammad bin Abdulrachman Alhabsi (the Chairman)

- Said Aboebakar bin Abdullah bin Achmad Alatas (First Vice Chairman)

- Said Idroes bin Ahmad bin Mohamad Sjahab (Second Vice Chairman)

- Said Hoesain bin Ahmad bin Hoesin bin Semit (First Secretary)

- Said Moehamad bin Ahmad bin Hoesin bin Semit (Second Secretary)

- Said Salim bin Tahir bin Saleh Alhabsi (First Treasurer)

- Said Abdulqadir bin Hasan bin Abdulrachman Molagela (Second Treasurer)

The commissioners:

- Said Ali bin Abdulrachman bin Abdullah Alhabsi

- Said Alwi bin Tahir Alhadad

- Said Alwi bin Mochamad bin Tahir Alhadad

- Said Ahmad bin Abdullah bin Mochsin Assegaf

- Said Jahja bin Oesman bin Jahja

- Said Abdullah bin Aboebakar bin Salim Alhabsi

- Said Hasjim bin Mohamad bin Hasjim Alhabsi

- Said Hasan bin Sech Assolabiah Alaidroes

- Said Abdoellah bin Moehamad Alhadad

- Said Aloei bin Abdullah bin Hoesin Alaijdroes

- Said Tahir bin Hoesin bin Semit

- Sjech Salim bin Achmad bin Djoenet Bawazir

- Said Abdulrachman bin Abdilla bin Abdulrachman Alhabsi

- Said Ali bin Aloei bin Abdulrachman Alhabsi

- Said Abdullah bin Mohamad bin Achmad bin Hasan Alatas

The first headmaster of the Jamiat Kheir school was Habib Abūbakar bin ʻAli Shahāb who was also one of the founders of The Jamiat Kheir Education Foundation. He was also the writer of his autobiography, رحلة الأصفر (RIHLATUL ASHFAR). He was born in Batavia on October 24, 1870 CE (or 28 Rajab 1287 AH) and died in Batavia on March 18, 1944 (23 Rabi' al-thani 1363 AH) and was buried in the Tanah Abang cemetery, Jakarta. His father is ʻAli bin Abūbakar bin ʻUmar bin ʻAli bin ʻAbdullah bin Shahāb born in Dammun, a small village near Tarim, Hadhramaut. His mother is Muznah binti Said Naum, the daughter of the land endowment (Arabic: الوقف التربه, romanized: al-Waqf al-Turbah) foundation founder Shaikh Said Na'um.

The school board of Jamiat Kheir, having noticed that the facility in Pekojan could no longer able to accommodate the flow of prospective students which increased every year, excited to find a new larger location. Initially they planned to move Jamiat Kheir from Pekojan to a new location on Karet Weg street in Tanah Abang, but because the venue was planned for a hospital by the Dutch government (now it is occupied as the Puskesmas of Tanah Abang), with the initiative of Abūbakar bin Muḥammad al-Habshi (the Chairman of the board) in 1923, the Foundation bought a new 3,000 square metres (32,000 sq ft) land for the school. The building has been used as the center of operations until now.[7]

With the initiative of Aḥmad bin ʻAbdullah al-Saggaf in 1924, a building for boarding students often called Internaat was built. The purpose of the Internaat was to protect, to educate and to familiarize the students with good Islamic traditions. The cost was determined 30 guilders a month. At internaat, they were directed and guided in order to fill their time with any good activities for the soul and body. The Jamiat Kheir's Internaat was opened on May 15, 1924 by occupying two houses on the Jalan Karet number 72. On March 26, 1929, the foundation made another attempt to buy a 2,500 square metres (27,000 sq ft) plot of land in Kebun Melati which later used as girls-only Elementary School.[7]

Because there was the law forbidding Jamiat Kheir to open school branches in other cities with the same name, people then established schools with different names (although sametimes similar, especially in Arabic) but with the same spirit and most of them affiliated with the Jamiat Kheir in Batavia, such as al-Jamʻiyyah al-Khairīyah al-ʻArabiyah in Ampel, al-Mu’awanah in Cianjur, al-ʻArabiyah al-Islamiyah in Banyuwangi, and Shama'il Huda in Pekalongan. The Shama'il Huda school in Pekalongan was led by Muḥammad al-ʻIdroos. Like Jamiat Kheir, this school also hired teachers from the Middle East such as Shaikh Ibrahīm of Egypt. A year later the management changed, where ʻAbdullah al-Aṭṭas was appointed as the Principal, Muḥammad Salim al-Aṭṭas as the vice Principal, Hasan ʻAli al-Aṭṭas as Secretary, and Naṣr ʻAbdullah Bakri as Treasurer. The member of counsel consisted of Hasan ʻAlwi Shahāb, ʻIdroos Muḥammad al-Jufri, Saqqaf Jaʻfar al-Saqqaf, Muḥammad ʻUmar Abdat, Cik Saleh Ismaʻil, ʻAbdulqadir Hasan, Sālim ʻUbaidah and Zen Muḥammad Bin Yaḥya. The schools were not exclusive to Arab Indonesians only, but also many of the pupils were of indigenous Indonesians.[1]

Due to lack of qualified teachers to teach at the Jamiat Kheir schools, the board decided to hire teachers from overseas. In around October 1911, a Sudanese scholar name Ahmad Surkati arrived in Batavia along with two other teachers, Muḥammad bin ʻAbdul Ḥamid (a Sudanese living in Mecca) and Muḥammad al-ṭayyib, a Moroccan who soon returned to his homeland. They had been preceded by another teacher, the Tunisian Muḥammad bin ʻUthman al-Hashimi who had come to the Indies in 1910. Soon after they arrived in Batavia, Jamiat Kheir opened two branch schools, one was located in Bogor and directed by Muḥammad 'Abd al-Ḥamid, and the other was at Pekojan (in Batavia), directed by Muḥammad al-Tayyib. Surkati was appointed as the inspector for both the Jamiat Kheir schools but based in Batavia.

Surkati's first two years at this position was a great success, creating an assurance for the Jamiat Kheir to hire four more foreign teachers in October 1913.[8] It was on his recommendation that Jamiat Kheir invited other teachers from abroad. In 1912 one of his own brothers, joined by three other teachers, came to Batavia. They included Abu al-Fadl Muḥammad al-Sāti al-Surkati (Surkati's brother), Shaykh Muḥammad Nur bin Muḥammad Khayr al-Anṣari, Shaikh Muhamnmad al-'Aqib and Shaikh Hasan Ḥamid al-Anṣari. All of them were from Sudan. They all joined Aḥmad Surkati in Batavia except Shaikh Muḥammad al-'Aqib who launched a new Jamiat school branch in Surabaya.[9]

Conflict

Some of more conservative Sayyid members of the Jamiat Kheir were becoming increasingly concerned about Surkati's influence on the Hadhrami community, and particular his attitudes towards the Sayyids themselves. It became more serious in 1913 when Surkati was asked during his visit to Solo during school holidays about his opinion on a marriage between a Sayyid woman with a non-Sayyid man. The case concerned a woman, a daughter of a Sayyid, who was living as concubine with a Chinese. Surkati suggested that money should be collected from among the local Haḍramis in order to release her from such a shameful circumstance which was apparently driven by economic hardship. When the proposal was ignored, he then suggested that one of the local Muslims should marry her. When the objection was put that her marriage to a non-Sayyid would be illegal on the basis of Kafa'ah, he argued it would be legal according to a reformist interpretation of Islamic law. His opinion was quickly heard by the Jamiat Kheir leaders in Batavia, causing his relationship with the more conservative Sayyids deteriorated rapidly.[8]

Sukarti also experienced racist criticism against him over this conflict.[10] The name "'Alawi-Irshadi conflict" became applied to the split between the Sayyid faction (known as 'Alawis, Alawīyūn) and the non-Sayyids (al-Irshād led by Surkati). The 'Alawi Sayyid Muhammad bin 'Abdullāh al-'Aṭṭās even said "The al-Irshad organization, in my view, is no pure Arab organization. There is too much African blood among its members for that".[11] 'Abdullāh Daḥlān attacked Surkati's stance that all humans whether Sayyid or non-Sayyid were equal by arguing that God creating some humans like the Prophet's family (the Sayyids) as superior to others. He said, "will the Negro return from his error or persist in his stubbornness?"[12] Some Hadrami Sayyids including Daḥlān resorted to extreme racist results and insulted Sukarti, calling him "the black death", "black slave", "the black", "the Sudanese" and "the Negro", all while claiming that Sukarti could not speak Arabic and was a non-Arab.[13]

Aḥmad Surkati was silent and could not reply with any arguments when his opinion was contested by ʻAbdullah bin Muḥammad Sadaqah Dahlan, who later replaced his position, with the same strong arguments based on al-Quran and sound sunnah. A rebuttal was even written by ʻAbdullah al-Aqib, one of Surkati's student, with the title of al-Khitab Faṣl fi Taʻyid al-Sūrah.[14] In addition to Dahlan's writing, there are other writings that discuss kafa'ah among Alawi, one of them is al-Burhān al-Nuroni fi Dahḍ Muftaroyāt al-Sinari al-Sudani by Habib ʻAlwi bin Husein Mudaihij. Further arguments written by Surkati and supporters eroded out by the book published in 1926 entitled al-Qaul al-Faṣl fī mā li Bani Hāshim wa Quraish wa al-Arab min al-Faḍl written by Mufti of Johor ʻAlwi bin Țahir al-Haddad.

Surkati then wrote his arguments and answers in Al-Masa `il ats-Tsalats in 1925 which contained the issue of Ijtihad, Bid‘ah, Sunnah, Heresy, Ziyarat (visiting graves), Taqbil (kissing the hands of Sayyids)[15][16] and Tawassul. This essay paper actually was prepared as the material for a debate with Ali al-Thayyib of the Ba'alawi. The debate itself was initially planned to be held in Bandung. But Ali al-Thayyib cancelled it and asked the debate to be held in Masjid Ampel in Surabaya. But eventually he cancelled it again so there was no debate at all.[9]

Surkati tendered his resignation on September 18, 1914.[8] Many non-Sayyids and some Sayyids left the Jamiat Kheir with him. He initially intended to return to Mecca where he used to teach, but was persuaded to stay by a non-Sayyid Hadhrami named ʻUmar Manqush (or Mangus with another transliteration), the Kapitein der Arabieren in Batavia, so he opened another Islamic school named al-Irshād in Batavia with the financial assistance of some Arabs, the largest of which from ʻAbdullah bin ʻAlwi Alaṭṭas, a wealthy landlord living in Petamburan, Batavia, who donated 60,000 Dutch gulden.[8][14]

The Surkati's quit from the Jamiat Kheir was not really caused by religious differences, but was more influenced by conspiracy of the Dutch Indies colonial government that has been arranged by ʻUmar Mangush and Rinkes, The Dutch adviser for Arab and indigenous communities. The relationship of these three had been previously established to create conflict among the Muslim community and for personal interests. Since early days, the Alawiyyin had advised Surkati through the Jamiat Kheir to not be associated with ʻUmar Mangush and Rinkes, but Surkati refused their request. The close relationship between Surkati, ʻUmar Mangush and the Dutch colonial government, making the Dutch authorities always intervened to help the difficulties between them and al-Irshād.[14][17]

Present time

In subsequent years Jamiat Kheir concentrates its activities only in education, while the al-Rabiṭah al-'Alawiyah continues the original purpose and activities of Jamiat Kheir (non-education related social activities). Some founders of the al-Rabiṭah who were also administrators of Jamiat Kheir, among others were Muḥammad bin ʻAbdurrahman bin Aḥmad Idrus Shahāb, Idrus bin Aḥmad Shahāb, ʻAli bin Aḥmad Shahāb, Shaikhan bin Aḥmad Shahāb, Abūbakar bin ʻAbdullah al-Aṭṭas and Abūbakar bin Muḥammad al-habshī. The first student financed by the al-Rabiṭah to graduate from Jamiat Kheir was Sharifah Qamar of Darul Aytam, where she received stipend of 15 guilders a month.

Currently the schools are run under Yayasan Pendidikan Jamiat Kheir (The Education Foundation of Jamiat Kheir). The Foundation has elementary, middle and high schools as well as an undergraduate college which are all located in Tanah Abang, where for the elementary and middle schools, they are Single-sex schools. In 2005 The Foundation built another elementary school with different name, Binakheir, in Depok.[18]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Sejarah Perkumpulan Jamiat Kheir (1901 – 1919)". 2 May 2009. Retrieved Jun 11, 2014.

- 1 2 "Chinatown – Arabtown". Retrieved Jun 16, 2014.

- ↑ Darul Aqsha (2005). Kiai Haji Mas Mansur, 1896-1946: perjuangan dan pemikiran (in Indonesian). Erlangga. p. 12. ISBN 978-97978-11457.

- ↑ "Jan Willem Roeloffs Valk". Oorlogsgravenstichting. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ↑ "Dirk Johannes Michiel de Hondt". Oorlogsgravenstichting. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- 1 2 3 "Pelopor Kebangkitan Nasional: Budi Utomo atau Jamiat Kheir?" (in Indonesian). Retrieved Jun 12, 2014.

- 1 2 "Yayasan Pendidikan Jamiat Kheir" (in Indonesian). 14 August 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Mobini-Kesheh, Natalie (1999). The Hadrami Awakening: Community and Identity in the Netherlands East Indies, 1900-1942 (illustrated ed.). EAP Publications. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-08772-77279.

- 1 2 Affandi, Bisri (March 1976). "Ahmad Surkati: His role in al-Irshad movement in Java" (thesis). Montreal: McGill University: 52–54.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Anthropologica, Part 157 2001, p. 413.

- ↑ Mobini-Kesheh 1999, p. 91.

- ↑ Mobini-Kesheh 1999, p. 96.

- ↑ Mobini-Kesheh 1999, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 bin Mashhoor, Idroos (14 August 2008). "Jamiat Kheir dan al-Irsyad" (in Indonesian). Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ↑ Affandi, Bisri (March 1976). "Shaikh Ahmad al-Surkati: His Role in al-Irshad Movement in Java in The Early Twentieth Century" (thesis). Institute of Islamic Studies: McGill University.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Boxberger, Linda (2002). On the Edge of Empire: Hadhramawt, Emigration, and the Indian Ocean, 1880s-1930s (illustrated ed.). New York: SUNY Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0791452189.

- ↑ Algadri, Hamid (1994). Dutch Policy Against Islam and Indonesians of Arab Descent in Indonesia. LP3ES. ISBN 978-9798391347.

- ↑ "Sejarah Binakheir". SDI Binakheir School. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

Bibliography

- Idrus Alwi Al-Masyhur (2006). Jamiat Kheir: mengangkat martabat bangsa (in Indonesian). Al-Mustarsyidin.

- Nafilah Abdullah (1999). Gerakan Jamiat Kheir: kajian tentang kontinuitas dan perubahan : laporan penelitian individual (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Proyek Perguruan Tinggi Agama, IAIN Sunan Kalijaga.

- van Bruinessen, Martin (1995). "Muslims of The Dutch East Indies And The Caliphate Question" (PDF). Studia Islamika. Jakarta. 2 (3): 115–140. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- Adam, Ahmat (1995). The Vernacular Press and the Emergence of Modern Indonesian Consciousness (1855-1913). SEAP Publications. p. 160. ISBN 9780877277163.

- M. Federspiel, Howard (2009). Persatuan Islam Islamic Reform in Twentieth Century Indonesia. Equinox Publishing. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-60283-9747-6.

- Noer, Deliar (1963). The Rise and Development of the Modernist Muslim Movement in Indonesia During the Dutch Colonial Period, 1900-1942. the University of Michigan.

- Noer, Deliar (March 2013). "The Modernist Muslim Movement in Indonesia, 1900–1942" (PDF). American Journal of Sociology. The University of Chicago Press. 118 (5): 1467–1473. doi:10.1086/670524. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- van Bruinessen, Martin (1999). "Controversies and Polemics Involving the Sufi Orders in Twentieth-Century Indonesia (in: Islamic Mysticism Contested:Thirteen Centuries of Controversies and Polemics by Frederick de Jong and Bernd Radtke)". Islamic Mysticism Contested. Leiden: Brill: 705–728.

- Marjani, Gustiana Isya (February 27, 2007). Concept of Religious Tolerance in Nahdhatul Ulama (NU): Study on the Responses of NU to the Government's Policies on Islamic Affairs in Indonesia on the Perspective of Tolerance (1984-1999) (PDF) (Doctoral dissertation). Universität Hamburg. Retrieved June 12, 2014.