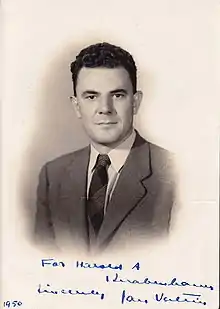

Richard Julius Hermann Krebs (December 17, 1905 - January 1, 1951), better known by his alias Jan Valtin, was a German writer during the interwar period. He settled in the United States in 1938, and in 1940 (as Valtin) wrote his bestselling book Out of the Night.

Background

Krebs became active in the Communist movement as a boy, when his father was involved in the naval mutiny that heralded the German Revolution of 1918–19.

Career

In 1923, he saw action in the failed Communist insurgency in Hamburg. Sometime after this he joined the German Communist Party, but was later expelled.

Arrest

In 1926, Krebs entered the United States illegally and moved to California. He spent 38 months in San Quentin State Prison for attempting to murder a merchant navy seaman during a brawl, then was deported to Germany in 1929. He worked as a seaman until 1934, when he was arrested and tortured, and acted as a witness for prosecution in a trial that brought to the conviction of a fellow German seaman accused of treason.

Out of the Night

In 1938, he returned to the United States to settle, this time under his most famous alias, Jan Valtin - where he published the highly publicized autobiography Out of the Night. In the book he described in detail the actions he supposedly had carried on as a secret agent of the Soviet GPU. The 1926 attempted murder was described by Krebs/Valtin as a GPU operation. The book received great critical acclaim. A 1940 review for the Saturday Review of Literature reads: "No other books more clearly reveals the aid which Stalin gave to Hitler before he won power".[1]

Congressional testimony

Valtin/Krebs was invited to testify before the Dies Committee as regards Soviet secret activities in Europe.

On May 26, 1941, Richard Julius Krebs testified before the House of Representatives' Subcommittee of the Special Committee to Investigate Un-American Activities (the "Dies Committee") that he had worked for the Gestapo for the Comintern. Research director J.B. Matthews had Sender Garlin had reviewed Out of the Night unfavorably in the Daily Worker newspaper of January 21, 1941. Garlin claimed no "Jan Valtin" existed and that the book's authors were Isaac Don Levine, Walter Krivitsky, and Freda Utley (known ex- or anti-communists). Krebs said he had defected in December 1937 - January 1938.[2]

Arrest

In November 1942, Krebs was also indicted as a Gestapo agent. He was arrested in December 1942 and found innocent in May 1943. The Los Angeles court record revealed that the 1926 crime had no political purpose. This event marked the end of Krebs/Valtin's career as a "Soviet expert". The New York Mirror said about his book Out of the Night: "In effect, the decision means he perpetrated a huge literary hoax."[3]

US war service

In August 1943, Krebs was drafted as an infantryman and deployed in February 1944 to the Philippines in fighting the Japanese in the Pacific War. In 1946, his book Children of Yesterday, an anecdotal history of the 24th Infantry Division was published, describing in graphic detail the horrors of the fighting and everyday life of the division's troops.

He was granted citizenship in 1947.

Personal life and death

Valtin/Krebs married again, before 1941, to Abigail Harris, an American. At the time of his death The Evening Star newspaper reported that he had been married three times, his third wife being Clara Medders of Chestertown, Md., and that he had three sons from his previous marriages.[4]

Richard Krebs died at the Kent-Queen Anne's Hospital on the evening of January 1, 1951 from lobar pneumonia. Prior to his death he had resided in Betterton, Md. for about six years.[4]

The Board of Immigration Appeals declared:

His life has been so marked with violence, intrigue and treachery that it would be difficult, if not wholly unwarranted, to conclude that his present reliability and good character have been established. [...] Within the past five years the subject has been considered an agent of Nazi Germany. On the record before us it appears he has been completely untrustworthy and amoral."[5]

The truth, however, is more complex. After he served his time in custody as ordered by US immigration authorities, he led a useful life putting the allegations of amorality and untrustworthiness to the lie. Then, late in life, Richard Krebs came to the service of his country in the clandestine anti-communist efforts launched by the US intelligence agencies still operating in Europe in the early years of the Cold War. To understand this view see SPYWRITER: Richard Krebs’ Astonishing Journey from German Communist Conspirator to American Combat Hero.[6]

Works

References

- ↑ Freda Utley, Saturday Review of Books, n. 23, 1940, p. 176.

- ↑ Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities. US GPO. 1941. pp. 8480-8507, 8481 (Comintern, defection), 8481-2 (Garlin). Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ↑ New York Mirror, November 25, 1942.

- 1 2 The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.) - January 2, 1951. p. 16

- ↑ John V. Fleming, The Anti-Communist Manifestos. The Four Books that Shaped the Cold War, W. W. Norton & Company, 2010, p. 167.

- ↑ Mattson, Roger (2020). Spywriter: Richard Krebs' Astonishing Journey from Communist Conspirator to American Combat Veteran (First ed.). Amazon. p. 428. ISBN 9798696920542.

- ↑ Valtin, Jan (1940). Out of the Night. Alliance Book Corporation. LCCN 41005066.

- ↑ Valtin, Jan (1942). Bend in the River. Alliance Book Corporation. LCCN 42008735.

- ↑ Valtin, Jan (1946). Children of Yesterday. Readers' Press. LCCN 46006264.

- ↑ Valtin, Jan (1947). Castle in the Sand. Beechhurst Press. LCCN 47011731.

- ↑ Valtin, Jan (1950). Wintertime. Rinehart. LCCN 50007162.