Japanese Surrendered Personnel (JSP) was a designation for Japanese prisoners of war developed by the government of Japan in 1945 after the end of World War II in Asia. It stipulated that Japanese prisoners of war in Allied custody would be designated as JSP, which were not subject to the Third Geneva Convention's rules on prisoners, and had few legal protections. The Japanese government presented this proposal to the Allies, which accepted it even though the concept lacked a legal basis, as they were suffering from manpower shortages.

Background

The concept of "Japanese Surrendered Personnel" (JSP) was developed by the government of Japan in 1945 after the end of World War II in Asia.[1] It stipulated that Japanese prisoners of war in Allied custody would be designated as JSP, since being a prisoner was largely incompatible with the Empire of Japan's military manuals and militaristic social norms; all JSP were not subject to the Third Geneva Convention's rules on prisoners, and had few legal protections. The Japanese government presented this proposal to the Allies, which accepted it even though the concept lacked a legal basis, as they were suffering from manpower shortages.[1]

Implementation

In 1945, the Allies began designating Japanese prisoners of war in their custody as JSP. The Allied power most involved in this was the British Empire, which was looking for manpower sources to counter logistical problems and reassert European control over their Asian colonies after the war. In addition to reestablishing their authority in British colonies which had been occupied by Japanese forces during the conflict, Britain initially supported French and Dutch efforts to regain control over French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies respectively.[2] The Netherlands Indies Civil Administration also made use of JSP.

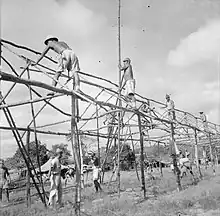

Due to a severe manpower shortage after 1945, JSP were not just used as guards and labourers by the British but were frequently pressed into active combat duties as well. The retention of JSP by the British was repeatedly questioned by the United States, which disputed the concept's validity.[3] However, the United States Armed Forces utilised up to 80,000 Japanese prisoners of war in the Philippines in a similar manner for the duration of 1946, due to similar issues concerning manpower shortages. Just like the British, the Americans used them for roadworks, disposal of human corpses, waste treatment, deforestation, infrastructure maintenance and law enforcement duties.[4][5]

French Indochina

JSP were involved in the War in Vietnam from 1945 to 1946, which saw the British assist the French in reasserting control over their colony of French Indochina. In addition to carrying out fatigue duties, JSP also saw combat against Viet Minh forces alongside the British Armed Forces, British Colonial Auxiliary Forces and the French Armed Forces. The British operation to restore French colonial rule, codenamed "Operation Masterdom", was overwhelmingly successful. While the Viet Minh suffered at least 2,700 killed, Allied forces suffered less than 100 killed in total.

Dutch East Indies

While serving as Supreme Allied Commander of the South East Asia Command in 1946, Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma held overall command of over 35,000 armed JSP in the Dutch East Indies. Retaining their wartime uniforms, organisational structure and officer corps, armed JSP fought alongside Allied troops in the Indonesian National Revolution. Their performance was such that on November 1946, British Army general Philip Christison recommended a JSP, a major named Kido, be awarded the Distinguished Service Order. Other instances of JSP seeing combat service during the revolution include a Japanese infantry company which was deployed to Magelang to assist British forces stationed there; Kempeitai members being used to guard camps in Bogor and Japanese artillery units being used for offensives in Bandung, with the city's British garrison being reinforced by 1,500 armed JSP. Armed JSP also saw action at Semarang and Ambarawa.[6]

I of course knew that we had been forced to keep Japanese troops under arms to protect our lines of communication and vital areas... but it was nevertheless a great shock to me to find over a thousand Japanese troops guarding the nine miles of road from the airport to the town.[3]

Aftermath

Being aware of the potential questions that would be raised if it was discovered that they were using the same troops they had just fought against as laborers and soldiers, the Allies worked successfully to conceal the extent of Japanese involvement in these post-war activities.[7] The last JSP which had been captured by Allied forces during the Burma campaign and Operation Zipper returned to Japan in October 1947. By this point, all Japanese war criminals had been sentenced by Allied tribunals, and some JSP were deported to the Republic of China and the Soviet Union and subject to forced labour.[8] Several memoirs written by former JSP have been published. One of most famous is a memoir written by Aida Yuji titled Prisoner of the British: A Japanese Soldier’s Experience in Burma, which was published in 1966.[9]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Connor 2010, pp. 395–398.

- ↑ Andrew Roadnight (2002), "Sleeping with the Enemy: Britain, Japanese Troops and the Netherlands East Indies, 1945–1946", History Volume 87 Issue 286.

- 1 2 "Japanese Prisoners of War" by Philip Towle, Margaret Kosuge, Yōichi Kibata. p. 146 (Google.Books)

- ↑ George G. Lewis and John Mewha, History of Prisoner of War Utilization by the United States Army, 1776–1945, Department of the Army Pamphlet No. 20-213, 1955. p. 257. Available at .

- ↑ Lewis and Mewha, pp. 259–260.

- ↑ McMillan, Richard (2006). IThe British Occupation of Indonesia: 1945–1946. Routledge. ISBN 9781134254286.

- ↑ Andrew Roadnight, "Sleeping with the Enemy: Britain, Japanese Troops and the Netherlands East Indies, 1945–1946", History Volume 87 Issue 286.

- ↑ Dower, John W. (1999). Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II New York: W.W. Norton & Company / The New Press.

- ↑ Aida, Yuji (1966) Prisoner of the British. A Japanese Soldier’s Experience in Burma, trs.Hide Ishiguro, Louis Allen, Cresset Press, London.