Jean-Antoine Lépine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jean-Antoine Depigny 18 November 1720 Challex, France |

| Died | 31 May 1814 (aged 93) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Paris |

| Occupation(s) | Horologist, inventor |

| Notable work | Lépine calibre, etc. |

| Spouse | Madeleine-François Caron |

| Children | Pauline Lépine |

| Parent(s) | Philibert Depigny and Marie Girod |

Jean-Antoine Lépine (alternatively spelled L’Pine, LePine, Lepine, L’Epine, born Jean-Antoine Depigny; 18 November 1720 – 31 May 1814) was a French watchmaker. He contributed inventions which are still used in watchmaking today and was amongst the finest French watchmakers, who were contemporary world leaders in the field.[1]

Beginnings and appointment as clockmaker to the King

Since his childhood the horologist showed an inclination towards mechanical, beginning his horological career and making fast progress, in particular, under the direction of Mr. Decroze, manufacturer of Saconnex watches,[2] in the suburbs of Geneva (Switzerland).

He moved to Paris in 1744 when he was 24 years of age, serving as apprentice to André-Charles Caron (1698–1775), at that time clockmaker to Louis XV. In 1756 he married Caron's daughter and associated with him, under "Caron et Lépine", between 1756 and 1769.[3] Watches with a signature Caron et Lépine or equivalent are not known; apparently Lépine was independent to a certain extent. As early watches were not numbered, it is uncertain when Lépine began to sign watches with Lépine à Paris on the movement and partially L'Epine à Paris on the dial.

On 12 March 1762, he became maître horloger (master horologist) and probably since that year he was teacher of Abraham-Louis Breguet, to whom he had a business relation over many years. In the Breguet archive many watches are recorded as delivered by Lépine.

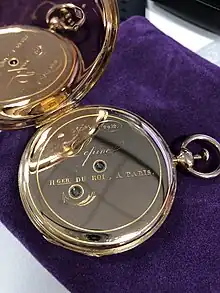

In 1765 or 1766 (precise date not known), he was appointed Horloger du Roi (Clockmaker to the King).

In 1766 he succeeded Caron, and appeared on the list of Paris clockmakers of that year as Jean-Antoine Lépine, Hger du Roy, rue Saint Denis, Place Saint Eustache. Ten years later, in 1772, he established himself in the Place Dauphine; in 1778-1779, Quai de l’Horloge du Palais; then in the rue des Fossés Saint Germain l’Auxerrois near the Louvre in 1781; and finally at 12 Place des Victoires in 1789. In 1782, his daughter Pauline married one of his workmen, Claude-Pierre Raguet (1753–1810), with whom he formed a partnership in 1792.

He was also associated for a certain period with the philosopher Voltaire, at his watch manufactory set up in 1770 at Ferney. It is not known the exact role he played in the Ferney Manufacture royale, either technical director and/or associate. However, most ebauches for his watches were made there, at least between 1778 and 1782. An unsigned memoir of 1784 reports that Lépine stayed in Ferney for 18 months and that he had watch movements made there with a value of 90,000 livres a year.

As a clock and watchmaker to Louis XV, Louis XVI and Napoleon Bonaparte, Lépine's creations were well respected and in demand.[3]

1764/65: Invention of the revolutionary Lépine calibre

Around 1764/65, he devised a means of manufacturing a pocket watch that could be thinner, favouring the onward quest for further miniaturization. His radical design broke with a 300-year tradition and ushered in the age of precision timekeeping, the modern pocket watch was born.[4]

In addition to paving the way for the making of even thinner watches, this innovation was readily adaptable as the basic model for mass-producing watch-movements, a process that was to begin in the nineteenth century. Up to the 1840s, watches were all hand-finished, so that parts were not interchangeable. The Swiss, Leschot in particular, believed there was a market for cheaper, machine made watches with interchangeable parts.[5] Refusing the incipient industrialization, French watch making only survived by becoming a peripheral adjunct to the Swiss watch making powerhouse, with only a few isolated Parisian cabinotiers still making truly French watches with French movements.[6]

The usual practice in the 18th century was to have the movement between two parallel plates and the balance wheel outside the top plate. The Lépine calibre discarded the top plate altogether and used individual cocks mounted on a single plate. This arrangement made it easier to assemble and repair the pocket watches, but also allowed the balance to be set to one side.

Essentially, the "Lépine calibre" or "calibre à pont", served to reduce a watch's thickness. To do this, it exchanged the traditional frame with two bottom plates for a single plate onto which the train is fixed with independent bridges. It also removed the fusee and its chain and then began using the cylinder escapement. He also invented the floating mainspring going barrel.

The Lépine calibre uses bars and bridges instead of pillars and upper plates. As mentioned, the movement has no fusee which equalizes the driving power transmitted to the train, replaced instead by a going barrel to drive the train directly. This improvement was facilitated by using the cylinder escapement and enhanced springs.

The calibre was quickly adopted throughout France and today its basic design is what characterizes all mechanical watches. It is important to note that the term "Lépine" can refer to both the calibre itself or a type of pocket watch with a flat, open-faced case in which the second wheel is placed in the axis of the winder shaft and the crown positioned at XII,[7] in opposition to the savonete (or hunter-case) watch where the second wheel and winder shaft are placed on perpendicular axes and the crown at III. This design has been known within the watch industry as the Lépine style ever since.[4]

Lépine's work profoundly influenced all subsequent watchmaking, particularly Abraham Louis Breguet who used a modified version of the "calibre ponts" for his ultra slim watches. Indeed, except from the very start of his career the celebrated and extremely well known Breguet almost always used Lépine calibres and then modified them. Along with Ferdinand Berthoud Lépine was master of Breguet.[8]

Other improvements and inventions

Throughout his career Lépine contributed with other important inventions[9] such as:

- He modified Jean-André Lepaute's virgule escapement. Thanks to Jean Antoine Lépine, it would be used for some twenty years or so in France.

- Invented a new repeating mechanism; in 1763 devised a mechanism in which by depressing the pendant the repeating spring is wound and where the hour and quarter racks were placed directly on the winding arbor. The new design was a great improvement, eliminating the fragile winding chain. It also gave the system better stability and decreased friction, while saving room and simplifying the mechanism. The 1763 Mémoire of the Académie des Sciences, in the chapter "Machines ou inventions approuvées par l’Académie en 1763", gave a very favorable report of Lépine's invention. The idea, with some modifications, still survives today.

- Invented a winding system requiring no key.

- Invented "lost hinge" watchcases (invisible); his "secret" opening mechanism with hidden hinges, releasing the back cover by twisting the pendant.

- The first horologist to have continuously study and work on aesthetic design, in the modern meaning of the word, on watches. This was continued by Breguet, etc.

- He was also the first one to use Arabic numerals on dials as many for the hours as for the minutes.

- Lépine is also credited for introducing hand-setting at the back of the watch and the hunter case (or savonette) that completely covers a dial with its spring-loaded hinged panel.

- He developed a new form of case, à charnières perdues (with concealed hinges) and a fixed bezel. Since these watches were rewound and set from the rear, the movement was protected from dust by an inner case. This new arrangement had the advantage of preventing access from the dial face, thus avoiding damaging it or the hands.

- The aiguilles à pomme apple shaped hands; hollow, tip hands, were first used by Lépine. In 1783 Breguet introduced a variation with eccentric "moon", and these are the most popular today, known as Breguet hands.

Legacy

In 1793–94 Lépine, when his tired eyes did not let him work further, handed over the "Maison Lépine" to his son-in-law Claude-Pierre Raguet who had become an associate in 1792, and when he died in 1810, his son Alexandre Raguet-Lépine continued the business. However, Jean-Antoine Lépine continued to be active in the firm until his demise, happened on May 31, 1814 at his home of Rue St. Anne in Paris. He was buried in a temporary concession in the Père-Lachaise cemetery on June 1, 1814.

The business was sold to Jean Paul Chapuy in 1815, employing Lepine's nephew Jacques Lépine (working from 1814 until 1825) who had been appointed clockmaker to the King of Westfalia (Germany) in 1809.[2] Later in 1827 it was sold to Deschamps who was succeeded in 1832 by Fabre (Favre). In 1853 passed to Boulay. 1885: Roux, Boulay's son in law. 1901: Ferdinand Verger. 1914: Last acquisition. 1919: Residual stock purchased by Louis Leroy. The business always continued under the name Lépine.[10]

Several of Lepine clocks and watches are on display in European museums and palaces, his timepieces are among the finest in the history of watchmaking.

He played a significant role in allowing us to strap watches onto our wrists.[3]

Historical associations

The horologist was patronised by leading figures of his day including the Comtesse d'Artois and de Provence, many French aristocracy as well as the Spanish, British and Swedish royalty.[11] Apart from monarchs, aristocrats, bourgeoises, etc., such was the popularity of Lépine's design that George Washington,[12] retired as President of the United States, searched for:

Dear Sir, I had the pleasure to receive by the last mail your letter dated the 12th of this month. I am much obliged by your offer of executing commissions for me in Europe, and shall take the liberty of charging you with one only. I wish to have a good gold watch procured for my own use; not a small, trifling, nor finically ornamented one, but a watch well executed in point of workmanship, and of about the size and kind of that which was procured by Mr. (Thomas) Jefferson for Mr. (James) Madison, which was large and flat. I imagine Mr. Jefferson can give you the best advice on the subject, as I am told this species of watches, which I have described, can be found cheaper and better fabricated in Paris than in London. (...)"

[13] Letter from George Washington to Gouverneur Morris. Mount Vernon, 28 November 1788.

The pocket watch he received through his emissary in Paris was from '"Mr. Lépine (who) is at the Head of his Profession here, and in Consequence asks more for his Work than any Body else. I therefore waited on Mr. L'Epine and agreed with him for two Watches exactly alike, one of which be for you and the other for me".[14] Gouverneur Morris in Paris 23 February 1789.

References

- ↑ "Malletantiques.com". mallettantiques.com. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- 1 2 "Worldtempus.com (In French)". worldtempus.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 Kannan Chandran, in Solitaire.com Archived 22 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 David Christianson, Masterpieces of Chronometry (2002): p. 53. Lépine and the modern watch

- ↑ Alan Costa, The History of Watches. In Watchcollectors.com

- ↑ "Homepage - TimeZone". www.timezone.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ "Accueil - Fondation de la Haute Horlogerie". www.hautehorlogerie.org. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ Lionel. "Breguet au Louvre". mini-site.louvre.fr. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ "Accueil - Fondation de la Haute Horlogerie". www.hautehorlogerie.org. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ G. H., Baillie, Watchmakers and Clockmakers of the World (1929): p. 195

- ↑ "Antique Clocks, Watches and Barometers". www.antique-horology.org. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ Benson J. Lossing, Mount Vernon and its associations, Historical, Biographical and Pictorial (1859): p. 207. A drawing of G. Washington's Lépine pocket watch

- ↑ Jared Sparks, The Writings of George Washington Vol. IX (1835): p. 449. Private letters

- ↑ David Christianson, Masterpieces of Chronometry (2002): p. 54. George Washington and Lépine

External links

- Evolution of Lépine calibres from 1800 until 1870

- A L. quarter repeating pocket watch circa 1780

- A ca. 1790 watch

- Quarter repeating and calendar, ca. 1798

- Another Lépine quarter repeating p. watch circa 1816

- Time in Office: Presidential Timepieces slideshow, among them G. Washington's Lépine pocket watch

- Famous watchmakers