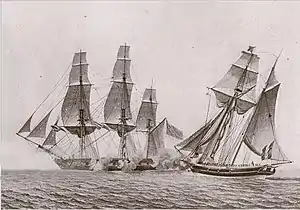

Jean Bart boarding Eagle on 9 February 1810 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Jean Bart |

| Namesake | Jean Bart |

| Builder | Marseille |

| Launched | 1807 |

| Captured | 23 February 1812, by HMS Blossom |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | schooner (of balaou, a type of schooner)[1] |

| Tons burthen | 108 tons[1] |

| Propulsion | Sail |

| Sail plan | 2-masted schooner[1] |

| Crew | 12 officers, 103 men[1] |

| Armament |

|

Jean Bart was a French privateer launched in Marseille in 1807,[1] and commissioned as a privateer by the Daumas brothers.[2] She was the first privateer captained by Jean-Joseph Roux.

She is depicted in two watercolours by Antoine Roux the Elder, dated 1810 and 1811.[1]

Career

First captain

Jean Bart sailed for her first cruise in 1807, returning to Marseille in 1808.[1]

Career under Jean-Joseph Roux

From May 1809 to July 1810, she was captained by Jean-Joseph Roux.[1] Jean Bart a 109-man crew, with four 12-pounder carronades, two six-pounder long guns, one chase 10-pounder gun mounted on a pivot at the bow, along with 60 rifles, 28 pistols, 33 sabres and 13 spears.[3]

The crew comprised 11 officiers (including one surgeon), 6 masters and 2 second masters (including two crew masters, two master gunners, one captain-at-arms, one master helmsman, one master carpenter and one load master), 17 able seamen (topmen, helmsmen and gunners), 20 seamen, 7 boys, 34 volunteers and 11 others.[4]

First cruise

On 4 June 1809, Jean Bart captured her first prize of the cruise, a Spanish merchantman laden with wheat, bound for San Feliu from Malta, and sent her to France.[5] On 13, she captured the British mercantile corvette Marie-Auguste (?), Joseph Tool, master, which was sailing from Alicante to Messina on ballast[5][Note 1]

On 19 June, Jean Bart captured two American ships: the 200-ton brig Elizabeth, and the 300-ton, 6-gun three-masted ship Weymouth, Gardner, master, both from Boston and bound for Palerme with loads of sugar, coffee, pepper, tobacco and various other goods. They were sent to France but the arrival of Elizabeth to France in unconfirmed, while Weymouth was recaptured.[5] The next day, she captured the British brig Liffey, from London and bound for Palerme with various goods, which surrendered after a brief artillery exchange,[6] and sent her to France.[5] On 1 July, Jean Bart was intercepted by a British cruiser, which she narrowly managed to elude after a running battle.[7]

From 3 to 9 August 1809, Jean Bart encountered four American merchantmen, but as Roux found no cause to seize them, he "regretfuly" had to send them on their way.[8][Note 2]

On 15 August, Jean Bart captured the Spanish pink Nuevo Cordeno, P.A. Bagon, master, which was sailing From Sardinia to Mahón with two passengers and a 5-man crew.[5][Note 3] The next day, she captured two Spanish ships: another pink, laden with wheat, and a three-masted polacca with unspecified cargo, both sailing from Sardinia to Mahón.[5][Note 4]

Second cruise

On her second cruise, Jean Bart captured the British mercantile corvette Eagle on 9 February 1810. Eagle, Thomas Walker, master, with a 15-man crew and 14 12-pounder guns, was bound from Palerma and Malta with four passengers and a load of leather, dye, blackwood, iron and various other goods.[5] Eagle put up a serious resistance and Roux had to board her before she surrendered, both ships sustaining two wounded each.[8] Jean Bart and Eagle arrived at Golfe Juan together on 1 or 2 December, but British cruisers forced them off Marseille and into a hide-and-seek chase; they eventually arrived at Toulon on 11 December.[4]

Roux had the mast of Jean Bart replaced by 25 December (a first replacement mast was found to be eaten by insects, and the second was too large and had to be worked upon before it would fit).[4]

On 11 March, she captured the British polacca Valetta, Edward Molley, master, bound from Malta to Bistol with a load of coton and various other goods. Valetta, of 4 12-pounder guns, had a 21-man crew.[5][Note 5] Valetta strongly resisted, first by long-range gunfire and, after one hour, as the ships were closing in to each other, intense artillery and musketry fire; Jean Bart eventually boarded Valetta, which only struck her colours after trying to repel the French with bladed weapons. Valetta had four seriously wounded, and Jean Bart sustained one killed and seven wounded.[8]

In the morning of 23 June 1810, Jean Bart encountered a British pink, which she attempted to attack; however, two brigantines soon joined in, exchanged signals with the pink, and engaged Jean Bart around 3 PM; after a three-hour exchange, Jean Bart had to limp away with 4 killed, 14 wounded (two of whom would die of their wounds in the next days), and having sustained serious damage to the rigging and hull.[9] The next day, having effected temporary repairs, Jean Bart captured the British Catherine, Philippe Medicy, master, bound from Malta to Mahón and Tarragona with a load of coton.[5][Note 6] However, the mainmast of Jean Bart was found to be more severely damaged by the battle of the 23rd than previously understood, and Roux set sail to return to Marseille.[9]

On 9 July, Jean Bart recaptured the Genoan ship Jesus and Maria, which the British privateer Intrepid had taken as prize. Jesus and Maria, Antoine Boggio, master, had been sailing from Ajaccio to Santa Margherita, near Genoa, with a load of iron, wheat and cheese, when she fell prey to Intrepid; her prize crew had been attempting to sail her to Malta when Jean Bart recaptured her.[5][Note 7]

Third cruise

Jean Bart departed for a third cruise, but on 26 November 1810, the mainmast of Jean Bart started splitting in two places and threatened to break, and Roux set heading North to return to Marseille and effect repairs. On 28, Jean Bart encountered the British brig Purita, Salvatore Antiniolo, master, bound from Matla to Gibraltar and Cadiz with a load of sulfur, oil, ropes, soap and various other goods, as well as two passengers; Purita had a 16-man crew and 6 guns. Roux sent her to France, where she is confirmed to have arrived.[5]

On 27 January, Jean Bart captured the American schooner Zebra, bound from Boston to Tarragona with a load of staves.[5] The next day, she captured the British 160-ton polacca Emma, which was returning from London to Malta with no cargo, a 9-man crew and 6 guns.[5] Emma fired a few cannon shots before surrendering.[6][Note 8]

On 2 February 1811, she captured the American 156-ton brig Star, John Holman, master, sailing from Salem to Palerma with an 11-man crew and a load of coffee, indigo, dye, spices and cod.[5] The next day, she seized the Swedish 300-ton Neutralité (?), John Tornberg, master, which was sailing from London to Cagliari with a 14-man crew and no cargo.[5] In both of these cases, Roux illegally displayed his true colours only after the masters of the ships had arrived aboard Jean Bart[Note 9] and produced their papers; the capture of Star was voided by the tribunal, probably for this reason.[6]

Career under Honoré Plaucheur

From October 1810 to February 1812, she cruised under Honoré Plaucheur, with 106 men and 5 guns. On 23 February, HMS Blossom captured her.

Fate

- On 23 February 1812, HMS Blossom captured Jean Bart.[10][1]

Notes

- ↑ Marie-Auguste was probably sent to France, but her arrival there is not confirmed by contemporary records.[5]

- ↑ Neutral ships, such as American or Swedish ships, could be seized if convicted of violating the Continental System by visiting British-controlled ships or ports; in absence of such proof, they had to be released.[8]

- ↑ Nuevo Cordeno was probably sent to France, but her arrival there is not confirmed by contemporary records.[5]

- ↑ The pink was probably sent to France, but her arrival there is not confirmed by contemporary records. The polacca did arrive in a French port.[5]

- ↑ Valetta was probably sent to France, but her arrival there is not confirmed by contemporary records.[5]

- ↑ Catherine was probably sent to France, but her arrival there is not confirmed by contemporary records.[5]

- ↑ Jesus and Maria was probably sent to France, but her arrival there is not confirmed by contemporary records.[5]

- ↑ Emma was probably sent to France, but her arrival there is not confirmed by contemporary records.[5]

- ↑ Which is in itself irregular: normally, the privateer's master was supposed to transport to a ship being stopped and inspecter her, rather than have the master come over.[5]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Demerliac, 1800-1815, n°2492, p.301

- ↑ Guerre et Commerce en Méditerranée, p.325

- ↑ Guerre et Commerce en Méditerranée, p.320

- 1 2 3 Guerre et Commerce en Méditerranée, p.323

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Guerre et Commerce en Méditerranée, p.333-334

- 1 2 3 Guerre et Commerce en Méditerranée, p.327

- ↑ Guerre et Commerce en Méditerranée, p.329

- 1 2 3 4 Guerre et Commerce en Méditerranée, p.328

- 1 2 Guerre et Commerce en Méditerranée, p.330

- ↑ "No. 16569". The London Gazette. 21 April 1812. p. 756.

References

- Boudriot, Jean. La Jacinthe, goélette, 1823 (in French). p. 35.

- Durteste, Louis (October 1991). "Un Corsaire de la fin de l'Empire : le Marseillais Jean-Joseph Roux, de 1809 à 1814". In Vergé-Franceschi, Michel (ed.). Guerre et commerce en Méditerranée IXe-XXe siècles (in French). Henri Veyrier. pp. 317–337. ISBN 2-85199-581-2.

- Demerliac, Alain (2004). La Marine du Consulat et du Premier Empire: Nomenclature des Navires Français de 1800 A 1815 (in French). Éditions Ancre. ISBN 2-903179-30-1.

- La Roerie, G. Navires et Marins (in French). Vol. 2. p. 119.