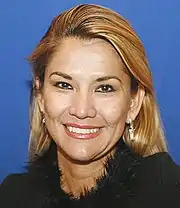

Jeanine Áñez | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Áñez at a visit to Reyes, 6 January 2020 | |||||||||||||||||

| 66th President of Bolivia | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 November 2019 – 8 November 2020 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Vacant | ||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Evo Morales | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Luis Arce | ||||||||||||||||

| President of the Senate | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 November 2019[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Adriana Salvatierra | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Eva Copa | ||||||||||||||||

| Second Vice President of the Senate | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 18 January 2019 – 12 November 2019 | |||||||||||||||||

| President | Adriana Salvatierra | ||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | María Elva Pinckert | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Carmen Eva Gonzales | ||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 January 2015 – 20 January 2016 | |||||||||||||||||

| President | José Alberto Gonzáles | ||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Jimena Torres | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Yerko Núñez | ||||||||||||||||

| Senator for Beni | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 18 January 2015 – 12 November 2019 | |||||||||||||||||

| Substitute | Franklin Valdivia | ||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Donny Chávez | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Pablo Gutiérrez | ||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 January 2010 – 10 July 2014 | |||||||||||||||||

| Substitute | Donny Chávez | ||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Mario Vargas | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Donny Chávez | ||||||||||||||||

| Constituent of the Constituent Assembly from Beni circumscription 61 | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 August 2006 – 14 December 2007 | |||||||||||||||||

| Constituency | Cercado | ||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||

| Born | Jeanine Áñez Chávez 13 June 1967 San Joaquín, Beni, Bolivia | ||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Social Democratic Movement (2013–2020) | ||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) |

Tadeo Ribera

(m. 1990, divorced)Héctor Hernando Hincapié | ||||||||||||||||

| Children | 2, including Carolina | ||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Jeanine Áñez Chávez (Spanish pronunciation: [ɟʝeˈnine ˈaɲes ˈtʃaβes] ⓘ; born 13 June 1967) is a Bolivian lawyer, politician, and television presenter who served as the 66th president of Bolivia from 2019 to 2020. A former member of the Social Democratic Movement, she previously served two terms as senator for Beni from 2015 to 2019 on behalf of the Democratic Unity coalition and from 2010 to 2014 on behalf of the National Convergence alliance. During this time, she served as second vice president of the Senate from 2015 to 2016 and in 2019 and, briefly, was president of the Senate, also in 2019. Before that, she served as a uninominal member of the Constituent Assembly from Beni, representing circumscription 61 from 2006 to 2007 on behalf of the Social Democratic Power alliance.

Born in San Joaquín, Beni, Áñez graduated as a lawyer from the José Ballivián Autonomous University, then worked in television journalism. An early advocate of departmental autonomy, in 2006, she was invited by the Social Democratic Power alliance to represent Beni in the 2006–2007 Constituent Assembly, charged with drafting a new constitution for Bolivia. Following the completion of that historic process, Áñez ran for senator for Beni with the National Convergence alliance, becoming one of the few former constituents to maintain a political career at the national level. Once in the Senate, the National Convergence caucus quickly fragmented, leading Áñez to abandon it in favor of the emergent Social Democratic Movement, an autonomist political party based in the eastern departments. Together with the Democrats, as a component of the Democratic Unity coalition, she was reelected senator in 2014. During her second term, Áñez served twice as second vice president of the Senate, making her the highest-ranking opposition legislator in that chamber during the social unrest the country faced in late 2019.

During this political crisis, and after the resignation of President Evo Morales and other officials in the line of succession, Áñez declared herself next in line to assume the presidency. On 12 November 2019, she installed an extraordinary session of the Plurinational Legislative Assembly that lacked quorum due to the absence of members of Morales' party, the Movement for Socialism (MAS-IPSP), who demanded security guarantees before attending. In a short session, Áñez declared herself president of the Senate, then used that position as a basis to assume constitutional succession to the presidency of the country endorsed by the Supreme Court of Justice.[4][5] Responding to domestic unrest, Áñez issued a decree removing criminal liability for military and police in dealing with protesters, which was repealed amid widespread condemnation following the Senkata and Sacaba massacres. Her government launched numerous criminal investigations into former MAS officials, for which she was accused of political persecution and retributive justice, terminated Bolivia's close links with the governments of Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, and warmed relations with the United States. After delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing protests, new elections were held in October 2020. Despite initially pledging not to, Áñez launched her own presidential campaign, contributing to criticism that she was not a neutral actor in the transition. She withdrew her candidacy a month before the election amid low poll numbers and fear of splitting the opposition vote against MAS candidate Luis Arce, who won the election.

Following the end of her mandate in November 2020, Áñez briefly retired to her residence in Trinidad, only to launch her Beni gubernatorial candidacy a month later. Despite being initially competitive, mounting judicial processes surrounding her time as president hampered her campaign, ultimately resulting in a third-place finish at the polls. Eight days after the election, Áñez was apprehended and charged with crimes related to her role in the alleged coup d'état of 2019; a move decried as political persecution by members of the political opposition and some in the international community, including the United States and European Union. Áñez's nearly fifteen month pre-trial detention caused a marked decline in her physical and mental health, and was denounced as abusive by her family. On 10 June 2022, after a three month trial, the First Sentencing Court of La Paz found Áñez guilty of breach of duties and resolutions contrary to the Constitution, sentencing her to ten years in prison. Following the verdict, her defense conveyed its intent to appeal, as did government prosecutors, seeking a harsher sentence.

Early life and career

Jeanine Áñez was born on 13 June 1967 in San Joaquín, Beni,[6] the youngest of seven siblings born to two teachers. Áñez spent her childhood in relative rural poverty; San Joaquín, at the time, lacked most essential services, including paved roads. Due to its limited access to power, electricity was only available at night, and her family spent long periods without light due to frequent interruptions in electrical service and a lack of diesel; water, additionally, was distributed only at scheduled times. Nonetheless, Áñez has recalled that she "had a beautiful childhood, very free" and affirmed that the town's conditions made children "grow up more open, freer, enjoying nature".[7]

From first to fifth grade, Áñez attended the 21 August School, a small, all-girls school, of which her mother was the director. After graduating high school at the age of seventeen, she left San Joaquín for La Paz to pursue studies in secretarial work, attending the Bolivian Institute before completing her education at the Lincoln Institute. After that, Áñez settled in Santa Cruz in order to further her education, completing secretarial, computing, and some English courses.[7] Later, she studied to become a lawyer at the José Ballivián Autonomous University of Beni in Trinidad, where she graduated with a degree in legal sciences and law.[8][9] Additionally, she holds diplomas in public and social management, human rights, and higher education.[10]

Before entering the political sphere, Áñez held a career in regional television journalism, including radio, which she described as her "great passion", though it was not well-paid.[11] In her first stint as a news presenter, Áñez received no salary, working under an exchange of services contract; for her work, the channel promoted the family's restaurant.[12] Later, Áñez came to serve as a presenter for the Trinidad-based television station Totalvisión, which she also later directed.[13] During this time, Áñez became an early supporter of the autonomist movement, conceived as a profound redesign of the country's existing centralized structure, expanding departmental self-determination over resources and providing for the election of regional authorities through universal suffrage. This movement, of which Áñez was a part of "from the beginning", concentrated its support in the eastern departments and represented one of the most important political and regional currents of the early 21st century in Bolivia.[14][15]

Constituent Assembly

Election

[For] many of us who are in this sector, it's the first time that we're participating in politics, and that's why we're here with the best intentions ... And if you want this Assembly to be foundational, then you'll have to redraft and consult the regions if you intend to belong to this nation that you're going to refound.

— Jeanine Áñez, Address to the president of the Constituent Assembly, 29 September 2006.[16]

In the context of the social reforms Bolivia undertook in the mid-2000s, Áñez emerged as a member of the generation of lowland politicians who entered the electoral arena in support of departmental autonomy. As most experienced political leaders had opted to present their candidacies in the municipal elections of 2004 and the legislative and prefectural elections of 2005, the 2006 Constituent Assembly elections provided an opportunity for young professionals with limited preexisting involvement with political parties to stand for office for the first time. In these circumstances, Áñez was invited by the opposition Social Democratic Power (Podemos) alliance to stand as a candidate in Beni circumscription 61 (Cercado) alongside Fernando Ávila. The Podemos binomial won the district.[17][18]

Tenure

The Constituent Assembly was inaugurated in Sucre on 6 August 2006.[19] Áñez entered the assembly "with great expectations" of codifying departmental autonomy into the statutes of the new constitution of the State but soon became frustrated by long delays in the drafting process brought about by the requirement of two-thirds support for the approval of articles.[15] During her term, she held positions on the Organization and New Structure of the State Commission and the Judiciary Commission, which participated in drafting articles related to the judicial branch of the new government.[20][21]

Chamber of Senators

First term (2010–2014)

2009 general election

Following the end of her term in the Constituent Assembly, Áñez remained close with Beni's prefect, Ernesto Suárez, who supported the establishment of a united opposition bloc to confront the Movement for Socialism (MAS-IPSP) in the 2009 general elections. The culmination of these efforts was the establishment of the political alliance Plan Progress for Bolivia – National Convergence (PPB-CN), which selected Áñez as its candidate for second senator for Beni. In this way, Áñez became one of the few former constituents who maintained a national-level political career after completing their work drafting the new constitution.[8]

Tenure

Senate directive disputes

The Senate's directive board—of which the Second Vice Presidency and Second Secretariat correspond to the opposition—was renewed in January 2011. The CN caucus nominated Áñez for the position of second vice president, though her designation failed to receive unanimity and had to be decided by a vote of the opposition legislators.[22] However, when the list of nominees was presented to be voted on by the full Senate, CN Senator Gerald Ortiz broke with the rest of his caucus and presented himself as a candidate for the position of second vice president. The opposition was ultimately unable to find consensus, leading the MAS to decide for it, electing members of both opposing blocs to different posts. Ortiz was designated second vice president while Áñez was elected second secretary, though she refused to assume the post.[23] She blamed the MAS for "endorsing transfuge" and for not abiding by the majority decision of the CN caucus.[24]

In the final year of her first term, Áñez was once again a primary figure in the internal disputes affecting the opposition. In January 2014, the Senate renewed its directive board to complete the 2010–2015 term of the Legislative Assembly. CN nominated Germán Antelo as second vice president and Áñez as second secretary but was again mired in conflict when Senator Marcelo Antezana presented himself separately for the second vice presidency. On 21 January, of the CN senators, Antelo and Antezana received a vote of six to zero, respectively, and Áñez received only five votes, leaving both disputed posts vacant due to the failure to achieve the required majority. As a result, neither Antelo nor Áñez managed to reach their originally prescribed positions, with the MAS electing Jimena Torres as second vice president and Antezana as second secretary on 24 January.[25][26]

2013 Beni gubernatorial election

In late 2012, Áñez was profiled as a potential contender to face Jessica Jordan of the MAS for the governorship of Beni in a special gubernatorial election. She was supported by CN, which presented her for consideration as a pre-candidate for the nomination due to her history as a human rights defender and her preexisting connections in the department.[27][28] Áñez faced ten other pre-candidates from various allied parties in a regional poll aimed at consolidating a single opposition candidacy for the election. Ultimately, Carmelo Lenz of Beni First emerged victorious and received the alliance's nomination.[29][30]

Second term (2015–2019)

2014 general election

During her first term, Áñez became affiliated with the political project of Santa Cruz Governor Rubén Costas. When Costas' civic group Truth and Social Democracy (Verdes) established itself as a regional political party in 2011, she attended its departmental congress as a representative for Governor Ernesto Suárez and Santa Cruz Mayor Percy Fernández.[31] In December 2013, she attended the first founding congress of the Social Democratic Movement (DEMÓCRATAS; MDS).[32] By early 2014, with the disintegration of CN as a viable political force and the dispersion of its members to other fronts, Áñez was already noted as one of the at least twenty assembly members who had joined the Democrats.[33] As part of the negotiations between the Democrats and the National Unity Front (UN) to form the Democratic Unity (UD) coalition, it was agreed that each party would define its own electoral lists in the departments in which they were most present. As a result, the MDS was allowed to designate candidates in Beni and Santa Cruz and, on 27 June 2014, Áñez—now the party's spokeswoman—announced that it had nominated her to go to reelection as its candidate for senator for Beni.[34][35]

In order to qualify as a candidate before the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), Áñez resigned her Senate seat on 10 July, ending her term early.[36] Two weeks later, on 25 July, the TSE certified her substitute, Donny Chávez, as the titular senator for Beni.[37] In the elections held on 12 October, UD lost in all but one department, Áñez's home department of Beni where she was reelected as senator.[38][39]

Tenure

Unlike in the previous legislative term, the vote to form the Senate's directive board for its 2015–2016 session took place without significant controversy. Áñez was elected second vice president of the Senate by a vote of thirty-five of the thirty-six senators,[lower-alpha 2] making her the UD coalition's representative in the Senate's directive.[40] In January 2019, it was UD's turn to appoint the head of the Second Secretariat to close out the 2015–2020 Legislative Assembly. Áñez, who planned on retiring upon the completion of her term, was tapped to assume the position with all the powers it entailed. However, she opted to exchange it with Christian Democratic Senator Víctor Hugo Zamora for the "more comfortable" second vice presidency, a "not a particularly fought-for" and largely ceremonial title.[41][42][43][44]

Presidency (2019–2020)

Succession to office

On 10 November 2019, after three weeks of increasingly fierce demonstrations, marches, and protests stemming from allegations of electoral fraud in that year's presidential election, President Evo Morales and Vice President Álvaro García Linera announced their resignations after over a decade in office.[45] Morales' abdication set in motion a series of further resignations of top MAS officials within his cabinet and the legislature. Within hours, Adriana Salvatierra and Víctor Borda, presidents of the Senate and Chamber of Deputies, respectively, presented their resignations, exhausting the constitutional line of succession to the presidency.[46][47]

Amid the vacuum of power, Áñez, as second vice president of the Senate, became the highest-ranking remaining member of the Senate's directive.[lower-alpha 3] As such, shortly after Salvatierra stepped down, Áñez reported to UNITEL that the task of assuming the presidency corresponded to her: "I am the second vice president, and in the constitutional order it would be up to me to assume [the presidency] with the sole objective of calling new elections".[49] Such a succession was not automatic, however, as an emergency session of the Legislative Assembly would have to be convened to first accept the resignations of the top officials.[50] Considering that the MAS held a two-thirds supermajority in the assembly, Áñez relayed her hope that the party would allow the required quorum to be reached.[51]

Áñez could not attend an emergency session of the assembly until the day after Morales' resignation, as she was in Beni at the time and there were no private Sunday flights from Trinidad to La Paz.[52] The following day, an emergency operation was mounted to transfer her from Trinidad to El Alto. On the morning of 11 November, she landed at the El Alto International Airport and was subsequently transferred in a military helicopter to La Paz.[53] The senator arrived at the Plaza Murillo amid strong security measures at 2:04 p.m., where she was received by former president Jorge Quiroga—a political actor during the crisis—and some of her Senate colleagues. Once inside the Legislative Assembly, Áñez announced that the country's senators would be summoned to an extraordinary session of the Senate to be held the following day, in which the resignations of the previous days were to be reviewed, and she would assume the presidency.[51]

At meetings sponsored by the Bolivian Episcopal Conference—the Catholic Church's authority in the country—and the European Union, opposition and ruling party delegates discussed the feasibility of Áñez's succession to the presidency as a possible solution to the power vacuum. Salvatierra and Susana Rivero—representing the MAS—rejected the idea, considering Áñez to be too closely aligned with Santa Cruz's political elite. Instead, they proposed that a new president be elected from among the MAS legislators or, if the new president be of the opposition, that it be Senator Zamora; both solutions were deemed unconstitutional. After further negotiations, the MAS representatives agreed to facilitate Áñez's succession, assuring that their caucus would attend that afternoon's legislative session.[44][54]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Jeanine Áñez assumes the interim presidency | |

_Hugo_Guti%C3%A9rrez%252C_Notimex.png.webp) Áñez is sworn in at an extraordinary session of the Legislative Assembly, 12 November 2019. | |

Later that day, in her capacity as second vice president of the Senate, Áñez formally called for the installation of an extraordinary session of the Senate, but it was immediately suspended due to the lack of quorum.[51] MAS legislators demanded security guarantees to attend the session: "We are predisposed towards a constitutional solution ... But we request the highest guarantees so that we can hold a session", said Betty Yañíquez, leader of the MAS caucus in the Chamber of Deputies.[55] Yañíquez argued that the MAS felt unsafe because civic leader Luis Fernando Camacho had announced a siege of the Plaza Murillo hours prior.[56] Deputy Juan Cala further detailed that the lack of guarantees had prevented the vast majority of MAS legislators from making their way to the capital; of the 119 MAS parliamentarians, Cala stated that only twenty percent had managed to arrive in La Paz.[57]

As a result, shortly after the session was suspended, Áñez appealed to Subsection (a) of Article 41 of the General Regulations of the Senate: "Replace the president [of the Senate] and the first vice president, when both are absent due to any impediment". Under this justification, Áñez declared that "it is up to me to assume the presidency of this chamber". With that, those present made their way to the hemicycle of the Plurinational Legislative Assembly, where she proceeded to install a new session of parliament, in which no MAS legislators participated. Áñez then appealed to Article 170 of the Constitution, which states that the president of the Senate will assume the presidency of the State in the case of a vacancy in that office and the vice presidency. Considering that Morales and García Linera had achieved asylum in Mexico hours prior, Áñez stated that this action "constitutes a material abandonment of their functions" and therefore "forces the activation of the presidential succession ... Consequently, here we are facing a presidential succession originated in the vacancy of the presidency ... which means that ... as president of the Chamber of Senators, I assume immediately the presidency of the State". As her assumption to office was brought about by an act of succession, Morales' resignation was therefore never read out, and no vote was taken. From the first attempt to install the session to Áñez becoming president, the entire process lasted eleven minutes and twenty seconds.[51][58]

The Bible returns to the Palace

Having secured the presidency, Áñez, together with other opposition legislators and civic leaders, including Camacho and Marco Pumari, made their way to the Palacio Quemado, the president's former residence prior to the construction of the Casa Grande del Pueblo in 2018.[59] Greeting a crowd of supporters, Áñez emerged onto the balcony dressed in the traditional presidential regalia, including the sash and historic presidential medal. Flanked by her two children on either side, as well as senators and civic leaders, she delivered a short speech pledging to "restore democracy to the country": "I am going to work this short time because Bolivians deserve to live in freedom, they deserve to live in democracy, and never again will their vote be stolen", she said.[60][61] Notably, Áñez, a Catholic, also brandished a small pink Bible, declaring that "God has allowed the Bible to enter the Palace again". Before Morales' presidency, and until 2009, Bolivia was not a secular state, and the former president's relationship with the Church was controversial.[62][63] At age fifty-two, Áñez was Bolivia's sixty-sixth president and is the second woman to have ever held the post, after Lidia Gueiler, who herself was a transitional president between 1979 and 1980.[64]

The following day, Salvatierra contended her resignation, arguing that, while she had publicly announced her intent to resign, Senate regulations establish that her letter of resignation had to be presented before a plenary session of the chamber in order for it to be approved or rejected by its members. Since such a vote had not occurred, some of her fellow assemblymen considered that Salvatierra was still president of the Senate and, therefore, the presidency of the State corresponded to her. Security personnel did not accept this justification and blocked Salvatierra and other MAS legislators from entering the Legislative Assembly, resulting in a scuffle between the opposing sides.[65][66] This prompted a further Senate session on 14 November—this time with the required quorum—in which Salvatierra's resignation was approved, and Eva Copa was elected to replace her as president of the Senate.[67] As part of the bill regulating the convocation of new elections, the majority MAS caucus formally recognized that Áñez's investiture had arisen through constitutional succession.[68]

Domestic reactions

_Cropped_I.jpg.webp)

Áñez's arrival to office was met with praise by Bolivian opposition and civic leaders. The first to congratulate her was former president Carlos Mesa—runner-up in the disputed presidential election—who wished Áñez success in carrying out the transition process.[69] Among members of her party, Governor Rubén Costas conveyed his hope that Áñez find "success in her crucial mission of leading the nation" while Senator Óscar Ortiz stated: "God bless and enlighten the new president of Bolivia". Former vice president Víctor Hugo Cárdenas expressed his hope that the new president "never forget the indigenous peoples, the Wiphala, the youth, and women" while politician and pastor Chi Hyun Chung asked that "God give her wisdom and strength".[70]

On the other hand, members of the deposed MAS expressed their discontent with Áñez's arrival to power and denounced what they viewed as a coup d'état. From Mexico, Morales tweeted that "the most cunning and disastrous coup in history has been carried out. A right-wing putschist senator proclaims herself president ... surrounded by a group of accomplices and managed by the Armed Forces".[71] García Linera similarly echoed Morales' coup rhetoric, blaming "racist backlash" for Morales' removal.[72]

Constitutional and legal analysis

Minutes after the conclusion of the session that declared Áñez president, the Plurinational Constitutional Court (TCP) released an official statement endorsing her succession as constitutional. Citing a 2001 Constitutional Declaration, the TCP affirmed that "the functioning of the executive body in an integral manner should not be suspended". Thus, constitutional succession to the presidency applied ipso facto to the next in line to take office; president of the Senate, in Áñez's case.[73] However, in a separate, unrelated ruling issued on 15 October 2021, the TCP clarified that automatic succession only applied to cases of vacancy in the presidency or vice presidency, not in cases of vacancies in the legislative chambers, due to the fact that the regulations of the Senate and Chamber of Deputies specify that all resignations must be first dealt with and accepted. MAS Deputy Anyelo Céspedes pointed out that, under this criteria, Áñez's succession to the presidency was unconstitutional because, as second vice president of the Senate, she could not have automatically assumed the presidency of the Senate. Mesa rejected that reasoning, stating that Morales' flight to Mexico left the presidency vacant, thus triggering an automatic succession to whoever was next in line for the presidency, which would have been Áñez regardless of whether she was president or vice president of the Senate.[74][75] Constitutional expert and jurist Williams Bascopé recalled that "Evo Morales' mistake was to ask for asylum and leave [the country], he left his post definitively, and that is why the constitutional succession has to operate without the need for parliament ... The Bolivian State cannot be left without command for a minute ...".[76] Nonetheless, Minister of Justice Iván Lima assured that the TCP's ruling definitively proved that Áñez's actions in assuming the presidency constituted a coup d'état.[77] In response, her lawyer, Luis Guillén, characterized the Court's decision as "tailored" to the interests of the MAS government to legitimize political persecution against her.[78]

Domestic policy

Response to unrest

Áñez's assumption to the presidency opened a new phase in the deep social unrest engulfing the country. Having succeeded in ousting Morales, civic leaders like Camacho and Pumari announced an end to mobilizations in Santa Cruz and Potosí in order to lift pressure on the government. On the other hand, social sectors related to MAS declared their own series of mobilizations with the aim of reversing the "coup d'état" and returning Morales to power. The brunt of these demonstrations were centered on the Chapare and El Alto—two historic centers of MAS support—where MAS-affiliated cocalero groups and trade unions threatened to impose blockades and cut off basic services to Cochabamba and La Paz if their demands were not met.[79]

In response, on 14 November, Áñez issued Supreme Decree N° 4078 regulating the intervention of the Armed Forces in the pacification process by exempting them "from criminal responsibility when, in compliance with their constitutional functions, they acted in legitimate defense or state of necessity". While the president assured that this did not constitute a "license to kill", international human rights organizations expressed their deep concern over its possible lethal implications and called for its immediate repeal.[80][81] The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) stated that the decree "encourages violent repression" while Amnesty International described it as a "carte blanche" for human rights abuses.[82][83] The MAS, meanwhile, moved to file a motion with the TCP to declare the decree unconstitutional.[80]

Within hours of the decree's promulgation, reports arose that security personnel in Sacaba had fired on cocalero protesters marching to Cochabamba, leaving multiple dead and dozens wounded. Four days later, on 19 November, clashes between police and demonstrators attempting to seize a YPFB plant in the Senkata barrio of El Alto resulted in further deaths. In both cases, the government denied that either the police or armed forces had been ordered to shoot.[84][85] Áñez lamented the loss of life, stating that "it hurts us because we are a government of peace".[86] Amid increasing pressure to reverse course, she abrogated the decree on 28 November, justifying that the government had "achieved the long-awaited pacification".[87]

At the government's invitation, the IACHR conducted an investigation into the incidents of violence that occurred during the pacification process. On 10 December, it released its preliminary observations in which it characterized the events in Sacaba and Senkata as massacres and condemned "serious human rights violations". The Commission reminded the Bolivian State that lethal force could not be used as a means of maintaining or restoring order and called on the government to implement measures to prohibit the use of force as a means of controlling public demonstrations. At the same time, the IACHR considered that the government did not have the conditions to conduct an impartial, internal inquiry and requested an international investigation be carried out.[88][89]

Legislative investigation

Seeking an oral report from the government regarding the Sacaba and Senkata massacres, the Legislative Assembly issued an interpellation against Áñez's ministers of government, Arturo Murillo, and defense, Luis Fernando López.[90] Both failed to attend their hearings, citing their official duties as reasons why they could not appear, leading the legislature to approve a formal request demanding that Áñez "instruct the Ministers of State to comply with their constitutional duties".[91] After failing to present himself three separate times, the Legislative Assembly voted to censure López, an action that entailed the minister's dismissal.[92] In compliance with the Constitution, Áñez replaced López on 9 March 2020, only to reappoint him the following day, arguing that the Constitution does not specify that a minister who has been censured and removed cannot return to their post.[93]

On 6 March—the same day as López's censure—the Legislative Assembly convened a multi-party mixed commission composed of six deputies and three senators of both the MAS and opposition to investigate the massacres.[94] On 29 October, meeting in a joint session of the outgoing Senate and Chamber of Deputies, the legislators approved the commission's report on the massacres of Senkata, Sacaba, and Yapacaní, which recommended a trial of responsibilities against Áñez for the crimes of resolutions contrary to the Constitution and the law, breach of duty, genocide, murder, serious injury, injury followed by death, criminal association, deprivation of liberty, and forced disappearance of persons. Additionally, it suggested an ordinary trial for eleven of her ministers as well as for certain members of the military and police. Copa announced that the commission's report would be submitted to the Prosecutor's Office in order to open proceedings.[95][96]

Electoral policy

Convocation of new elections

On 14 November 2019, Áñez announced the government's intent to call for fresh elections as soon as possible and by "any mechanisms necessary". She requested the cooperation of legislators from the Movement for Socialism, whose participation was essential in order to carry out the transitory process as they still maintained a parliamentary majority in both chambers of the assembly. In particular, the MAS's two-thirds vote was necessary to elect six of the seven members of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal to replace the previous officials—prosecuted for electoral crimes due to the disputed presidential elections. Áñez stipulated that these new authorities must be "honest, transparent professionals", though she accepted that the MAS "will have the opportunity to elect the authorities they want, that they decide, because that is their right".[97]

Due to the initial inability of the assembly to reach an agreement, the government evaluated the possibility of calling elections via supreme decree, an action that had precedent in the transitional government of Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé in 2005.[98] Morales, however, claimed that doing so would contravene the 2009 Constitution.[99] Copa also regarded the idea as unconstitutional: "we cannot allow an election to be held by decree when the Legislative Assembly is operating legally and legitimately".[100] She called on the president to avoid "manag[ing] everything by decree ... because Congress is the maximum expression of the Bolivian people".[101] For his part, Rodríguez Veltzé pointed out that his ability to manage the transition was only possible "via dialogue and political consensus". On 18 November, Jorge Quiroga presented two draft bills that he claimed would allow Áñez to call elections and designate members of the Supreme and Departmental Electoral Tribunals by way of decree, though he also stated that the ideal would be to solve the issue through the Legislative Assembly.[102]

.jpg.webp)

On 20 November, Áñez delivered a bill to advance the convocation of new elections and gave the assembly two days to reach a consensus; otherwise, she would issue the call by supreme decree.[103] On 23 November, the Senate unanimously approved the Law on the Exceptional and Transitory Regime for General Elections, consisting of twenty-four articles and five provisions that were subsequently passed by the Chamber of Deputies and promulgated by Áñez on 24 November. Under its provisions, the general elections of 2019 were declared null and void, and new elections were to be convened, though no concrete date was set. Additionally, new members of the TSE were to be elected within three weeks, who would then issue the call for general elections.[104][105] Notably, the rule mandated that individuals who had been re-elected to the same office for the two previous constitutional periods were barred from seeking the same position, thus prohibiting Morales from contesting the presidency.[106]

Áñez appointed Salvador Romero as the first member of the new TSE, who took office on 28 November.[107] The assembly elected six authorities to fill the remaining vacancies three weeks later, thus reconstituting the electoral body.[108] Though the TSE was initially mandated to set a date for new elections within forty-eight hours of taking office, it was later extended to ten days in order to grant its members the proper amount of preparatory time to organize the electoral calendar. On 3 January 2020, TSE magistrate Oscar Hassenteufel announced that 3 May had been set as the date for the new general elections.[109] However, given the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the TSE later requested that the elections be delayed, proposing 6 September as a suitable date. Between 31 March and 1 May, the Chamber of Deputies and Senate sanctioned a law delaying the election by ninety days from their originally scheduled date, setting 2 August as the new date. Áñez almost immediately filed an objection, arguing that it would be unfeasible to "forc[e] almost six million people to take to the streets in a single day ... in the midst of a pandemic"; she demanded that the TSE's September recommendation be approved instead. The five-page document was put into consideration at an emergency session of the Legislative Assembly. Within the hour, the majority-MAS legislature rejected the president's observations as unfounded, allowing Copa to promulgate the law without Áñez's involvement.[110][111] A month later, the TSE entered negotiations with contending political parties to secure a delay in the elections to its preferred date. On 2 June, Romero presented a bill to the Legislative Assembly that would set the elections for 6 September. The legislature ratified the agreement a week later, and Áñez promulgated it not long thereafter.[112][113]

Given the continued health crisis, the TSE postponed the elections to 18 October, doing so "in the use of its powers", thus circumventing the legislature's approval. The date change was supported by Áñez, the United Nations, and most contending parties, with the exception of the MAS, which outlined its intention to protest the decision.[114] For nearly two weeks, MAS-aligned protesters installed roadblocks and held marches, resulting in food shortages and delaying the transfer of medical supplies. In response, Áñez threatened to deploy police and military personnel the quell the protests, accusing demonstrators of causing the deaths of COVID-19 patients due to the inability to transport supplemental oxygen. Ultimately, however, the violence did not escalate, and demonstrations died down after they proved unpopular among ordinary Bolivians.[115]

Presidential campaign

Announcement

As early as 15 November 2019, in an interview with Will Grant for BBC Mundo, Áñez assured that she had no intentions of presenting herself as a presidential candidate. "I do not have that desire. My objective in this transitional government is to carry out transparent elections", she stated.[116] This sentiment was later reiterated by Minister of the Presidency Yerko Núñez and confirmed by the Agencia Boliviana de Información—the government press agency—which released an official statement claiming that "there are no political calculations behind [Áñez's] administration".[117] In a poll conducted between 9 and 13 January 2020 by Mercados y Muestras, the results found that, while forty-three percent of those surveyed rated Áñez's management as very good or good compared to twenty-seven percent who said it had been bad or very bad, only twenty-four percent agreed that she should present her candidacy for the presidency. In contrast, sixty-seven percent of respondents agreed with the statement that she must "not take advantage of her power to be a presidential candidate".[118]

Nonetheless, discussions regarding her possible candidacy permeated, and her party, the Democrats, began to promote it following its failure to reach an agreement with Camacho, who launched his own campaign. Finally, at a rally in La Paz held on 24 January 2020, Áñez launched her presidential campaign on behalf of the right-wing, Democrat-led Juntos alliance, justifying that the opposition's failure to consolidate had forced her to present herself as a unifying consensus candidate. Though she admitted that running for the presidency "was not in my plans" and that "some will find the measure difficult to understand", she argued that, in confronting the MAS, "we no longer have room to make mistakes".[119]

_Juntos.png.webp)

Both the opposition and the MAS decried Áñez's announcement. Her candidacy split the right into two fronts between Juntos and Creemos—the alliance of Camacho—who called on the president to "keep her word". For Mesa, whose centrist Civic Community (CC) coalition saw two of its major components split off to join Juntos, Áñez's decision to run was "a big mistake" that affected her ability to manage the transition "with neutrality".[119][120] Former president Jaime Paz Zamora was harsher, stating on Twitter that "the moral argument against a coup falls. They will say that what was sought was the seizure of power".[121] Morales affirmed that Áñez's candidacy was proof that she had carried out a coup against him.[122] In an opinion piece for The New York Times, journalist Sylvia Colombo stated that, in announcing her candidacy, Áñez "not only broke a promise but also took away from her interim government the best argument to convince skeptics that the departure of Evo Morales ... was not a coup".[123]

On the other hand, Costas claimed that "it's women's time" and assured that "Bolivia asked for [Áñez's candidacy] because she gave us peace back".[121] In an opinion column published by Correo del Sur, Samuel Doria Medina, leader of the National Unity Front, was initially critical of Áñez's for using "the resources of state institutions ... [to] benefit [herself]".[124] However, he quickly backtracked on that sentiment and, a week later, Áñez announced that Doria Medina would accompany her as her running mate.[125] "I trust [her promise] to avoid taking advantage of state resources [to benefit her campaign]", he said.[126] In that regard, it was pointed out that Áñez's campaign announcement had been broadcast on Bolivia TV, the State channel, causing an investigation to be opened within the Ministry of Communication.[127]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Áñez withdraws her candidacy | |

Jeanine Áñez announces her intent to drop out of the presidential race,17 September 2020. | |

Campaign and withdrawal

For most of the campaign season, Áñez came in at a distant third in polling data, behind Carlos Mesa and MAS candidate Luis Arce. However, on 16 September, a new poll moved her down to fourth place, behind Camacho. The same survey found that Arce would take forty percent of the vote, allowing him to win in the first round.[lower-alpha 4] As a result, the following day, Áñez disseminated a video message through her social networks announcing that she had chosen to withdraw her presidential candidacy in order to avoid a dispersion of the vote among the opposition. She characterized her decision as "not a sacrifice, [but] an honor", and stated that "if we [the opposition] don't unite, Morales will return, the dictatorship will return".[129]

Though analysts observed that Áñez's withdrawal could potentially boost Mesa's campaign enough to achieve a runoff—in which he was overwhelmingly favored to win—the results of 18 October ultimately indicated that Arce had won a surprise victory in the first round, reaching fifty-five percent of the vote.[130][131][132] Among the factors in the MAS's return to power, analysts cited Áñez's candidacy as a compounding reason for the opposition's inability to achieve victory. According to journalist Pablo Ortiz, the controversial Áñez administration broke one of the "first foundational myths of anti-Evismo: they were capable of committing the same acts of corruption and abuse of power as the MAS".[133] In addition, the repressions of Sacaba and Senkata and instances of racism in her government had a tremendous negative impact on the entire opposition's ability to gain support from Bolivia's indigenous population.[134]

COVID-19 pandemic

At the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, Áñez announced various biosecurity measures to combat the disease. Starting on 17 March 2020, Bolivia's international borders were closed to foreigners—but not Bolivian citizens—for forty-eight hours. Within seventy-two hours of her announcement, all international and national flights and interdepartmental and interprovincial land transport were suspended, save for an exemption for the transfer of goods to maintain supply chains. Domestically, from 18 March, the public and private working day was shortened to five hours between 8:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m., while local markets and supermarkets were allowed to remain open until 3:00 p.m. In addition, a curfew on traffic between the hours of 6:00 p.m. and 5:00 a.m. was set, except in cases where people needed to travel for work or urgent health-related reasons.[135]

Citing a lack of compliance with quarantine measures, Áñez declared a health emergency on 26 March. A strict, mandatory quarantine was imposed on the population: "No one leaves, nor does anyone enter the country", Áñez remarked. It was established that one person per family would be allowed to leave their homes between the hours of 7:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. to purchase groceries and other essentials, and all exits were prohibited on weekends. Those found not to be in compliance were to be charged a fine of Bs1,000 ($145), while drivers violating the prohibition of vehicles faced a fine of Bs2,000 ($289) and could be arrested for eight hours. To enforce these measures, the president stated that the "active participation of the Armed Forces and the National Police in the fight against the coronavirus" would be promoted by the government.[136] On 26 June, Áñez implemented the so-called "dynamic quarantine" until 31 July. Most preexisting regulations were kept in place at the national level, though sub-national governments were allowed to regulate aspects such as circulation of people, commerce, food delivery services, minimal social distancing, and transport within their jurisdiction.[137] At the beginning of August, this was extended until the end of the month, after which measures were significantly relaxed from September onward.[138][139]

Controversially, Áñez promulgated Supreme Decree N° 4231 on 7 May 2020, which intended to prevent the spread of COVID-19 misinformation. Under its provisions, any individual or media outlet found to have disseminated what was deemed as misinformation, be it through written, printed, or artistic form, could be subject to a criminal complaint by the Prosecutor's Office.[140] In response, on 14 May, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) deemed the decree excessive and requested that the Áñez administration modify it in order to "not to criminalize freedom of expression".[141] Áñez complied, and repealed the controversial decree within hours, a decision celebrated by both the MAS and the opposition.[142]

To combat the increase in economic instability, Áñez and her cabinet pledged to donate fifty percent of their monthly salary a fund to help those affected by the pandemic. The president's monthly salary is Bs24,251 ($3,520); that of a minister of State totals Bs 21,556 ($3,130); and that of a vice minister is Bs20,210 ($2,930). The initial sum was Bs250,000 ($36,290) per month, which the government hoped to increase with the support of parliamentarians, business people, and the rest of the population.[143] The government also pledged to pay domestic electricity and water tariffs from April through June 2020 to ease families' economic burdens. Eight in ten households received a 100 percent discount in May.[144] These bonds were claimed by all households in extreme poverty and ninety to ninety-six percent of those in moderate poverty.[145]

Cultural policy

Since the passage of the 2009 Constitution, the Wiphala—flag of the indigenous peoples of the Andes—has been the dual flag of Bolivia, alongside the national tricolor.[146] Upon taking the reins of government, Áñez instructed that the Wiphala be maintained as a national symbol of the State.[147] Additionally, her government incorporated the flag of the Patujú flower—emblem of the indigenous peoples of eastern Bolivia—as a co-official flag in all official acts at the national level.[148] While the Patujú flower was made a national symbol by the Constitution, prior to Áñez's presidency, the flag only served as a departmental symbol in Beni and Santa Cruz.[149] In January 2020, Áñez implemented a new government logo for usage by all ministries and vice ministries of the State. It featured the coat of arms in black and white, and below it, a line of colors representing the tricolor and Wiphala flanked on either side by two Patujú flowers.[150][151]

To increase funds to combat the pandemic, Áñez abolished three ministries on 4 June. Among these were the Ministry of Cultures and Tourism and the Ministry of Sports, which were merged with the Ministry of Education, a move that provoked backlash from indigenous groups and members of both the MAS and opposition. Áñez responded to their criticism by assuring that "art and culture will be promoted from the Ministry of Education".[152]

Judicial policy

As reported by The Washington Post, "[after] being sworn in, the fiercely anti-socialist Áñez ... presided over the detention of hundreds of opponents [and] the muzzling of journalists".[153] A month into her term, prosecutors issued an arrest warrant against Morales on charges of terrorism and sedition, accusing him of orchestrating violent protests intended to depose the transitional government.[154] A multitude of criminal processes, including charges of terrorism, sedition, and dereliction of duty, were levied against over 100 former officials, including many of the "strongmen" of the Morales administration, such as Juan Ramón Quintana and Javier Zavaleta.[155][156][157] After a thorough review of the case files, researchers from Human Rights Watch (HRW) deemed many of these charges to be "politically motivated", calling the twenty-year prison term sought for Morales "wholly disproportionate". According to César Muñoz, author of the HRW report, the Áñez administration "had a chance to ... strengthen judicial independence" after the rights group found that Morales used the judicial system to suppress opponents. "Instead, [Áñez] turned the justice system into a weapon to be used against [her own] political rivals", he stated.[155] For his part, José Luis Quiroga, policy director for the Mesa campaign, assured that "in many cases, they are doing exactly what [the MAS] did to their political enemies". "A simple accusation is made, and the prosecutor [sic?] and police go all out".[153]

Foreign policy

Israel

Just over two weeks into Áñez's mandate, on 28 November 2019, Foreign Minister Karen Longaric announced that the transitional government would seek to re-establish diplomatic relations with the State of Israel for the first time in over a decade. In 2009, President Morales cut off relations and labeled Israel a terrorist nation after it launched an offensive into the Gaza Strip that resulted in the deaths of over a thousand Palestinians. Longaric called his decision "a measure of a political nature without consideration [for] ... economic and commercial [ramifications]".[158][159] Israeli Foreign Minister Israel Katz hailed the new government's decision as a step forward for the country's international status.[160] Visa requirements for Israeli nationals entering the country were waived on 11 December, in conjunction with the elimination of the same restrictions on U.S. citizens.[161]

On 4 February 2020, Áñez received Asaf Ichilevich, Israeli ambassador to Peru with jurisdiction over Bolivia, and Shmulik Bass, director of Israel's department for South America, at the Palacio Quemado. Their meeting covered various forms of cooperation between the two states on issues related to agriculture, education, and health. At a press conference held shortly after, the government announced that officials from both countries had agreed on the formal resumption of relations between Bolivia and Israel.[162]

United States

Prior to Áñez's presidency, diplomatic relations between Bolivia and the United States had been suspended for the previous twelve years since the Morales administration expelled Ambassador Philip Goldberg in 2008 on accusations of espionage.[163] With the arrival of her government, Áñez moved to rekindle the country's ties with the U.S., and, on 26 November 2019, Óscar Serrate was appointed as an ambassador on special mission to the U.S. government. Various media outlets reported that this constituted a resumption of diplomatic relations between the two states, though Áñez's government clarified that Serrate was only on a temporary special mission and that the president chosen in the next elections would be allowed to decide whether or not to formally appoint an ambassador. In December, Beatriz Revollo—who served as consul in Washington, D.C. from 1997 to 2001—was reappointed and received credentials from the U.S.[164] In the same month, Áñez lifted visa requirements for American nationals entering the country.[161] On 21 January 2020, she and her foreign minister received U.S. Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs David Hale, with whom an intent to exchange ambassadors for the first time in over a decade was agreed to.[165]

Venezuela

Within two days of assuming office, the Áñez administration announced that it had decided to recognize opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the legitimate president of Venezuela.[166] The following day, Áñez, through Foreign Minister Longaric, reported that diplomats representing the government of Nicolás Maduro had been asked to return to Venezuela.[167] Additionally, the country's disassociation from the Bolivarian Alliance—led by Venezuela and Cuba—and its withdrawal from the Union of South American Nations were also announced, though the latter organization had already effectively ceased functioning.[168] On 22 December 2019, Bolivia formally entered the Lima Group, a regional bloc established to discuss diplomatic solutions to the crisis in Venezuela.[169]

Post-presidency (2020–2021)

Áñez was not present for the inauguration of her successor. On 7 November 2020, a day before Arce was sworn in, she announced that she had already departed La Paz and settled at her residence in Trinidad, Beni. From there, she pledged to continue to "defend ... democracy" and denounced possible judicial processes against her as political harassment.[170][171] She went on to deny anonymous reports that she intended to flee the country for Brazil and pointed to the MAS as the instigators of such rumors.[172]

Beni gubernatorial campaign

Shortly before the new year, on 27 December 2020, Áñez released a short video through her social networks communicating her resignation from the Social Democratic Movement. She criticized "old politicians" from both the left and the right whom she regarded as having impeded her ability to govern and stated that "a change is needed" in the country's political system.[173]

_Ahora!.svg.png.webp)

One day later, spokesman Jorge Ribera revealed that Áñez had agreed to run as a candidate for governor of the Beni Department on behalf of Ahora!, an alliance between the National Unity Front and Let's do it for Trinidad. He stated that the decision to nominate her stemmed from a recently conducted poll that indicated favorable results if she ran.[174] The following day, Áñez officially launched her gubernatorial candidacy. At a press conference, she recalled that she had been debating whether to assume that "former president's role" and withdraw from politics or accept UN's invitation to be its nominee and that she opted for the latter in order to fulfill her commitment "to work for my department".[175][176]

Áñez's electoral program focused on developing the department's agriculture industry and implementing a "Beni Bonus" to help families struggling in the pandemic.[177][178] Early polling indicated relatively even support between Áñez and Alejandro Unzueta of the Third System Movement, with each receiving twenty-one and twenty-seven percent of the voting intention; such an outcome would result in a runoff between the two. However, her campaign was disrupted by mounting judicial processes, which forced her to suspend electoral activities on some occasions.[177] Shortly after election day, Unzueta was declared the winner in the first round, with MAS candidate Alex Ferrier reaching second place. Áñez came in a distant third, receiving just thirteen percent of the vote.[179]

Arrest and prosecution (2021–present)

Apprehension

On the afternoon of 12 March 2021, the Prosecutor's Office issued an arrest warrant against Áñez, five of her former ministers, and multiple former members of the high command of the armed forces. The news was broken by Áñez herself, who published a photo of the document through her social networks, where she also denounced that "the political persecution has begun".[180][181] The charges against her for conspiracy, sedition, and terrorism stemmed from the coup d'état case, filed by former MAS deputy Lidia Patty in December of the previous year.[182] The move came as a surprise as that case was initially designed to prosecute members of the military and police for requesting Morales' resignation.[183]

At around 1:00 p.m., police surrounded Áñez's residence in Trinidad, but she was not found in her home, and a citywide search was carried out.[184] Áñez's nephews—Juan Carlos and Carlos Hugo, who were at her house at the time—were apprehended during the operation, accused by the Prosecutor's Office of hindering police work. After thirty-six hours in police custody, the Beni Fourth Criminal Investigation Court returned their freedom under alternative measures. Upon being released, Juan Carlos denounced that he had been forced through torture to disclose Áñez's location: "The policemen grabbed me and put me in the van without asking me anything, they took me to a room ... where they put a bag over my head and beat me. They wanted me to tell them where my aunt was, if I didn't, they were going to keep hitting me".[185] At dawn the following day, officers discovered Áñez hidden at a relative's home—presumed to be her mother—and she was placed under arrest.[183]

Reactions

The Associated Press described Áñez's apprehension as a "crackdown on opposition".[186] Jim Shultz, founder of the Bolivia-focused Democracy Center, warned that the incident represented a "cycle of retribution" in the country's justice system: "[This] feels less like a legal process and more like they are taking turns trying to destroy one another". He noted that while Áñez faced valid accusations of human rights violations and political persecution, the charges levied against her were not related to that. He considered the coup allegations for which she is prosecuted to be "a stretch".[187] After reviewing her case file, Human Rights Watch found the evidence against Áñez to be "unclear". In an op-ed published by El País, the organization stated that "victims will not be served by one-sided investigations that violate due process ... During the Áñez administration, we called on prosecutors to drop abusive charges and uphold human rights. We ask the same now".[188]

According to political analyst Marcelo Arequipa, "the Bolivian political crisis was supposed to have been resolved with the general elections last year ..., [but Áñez's arrest] has brought us back to ... a scenario of social polarization". Protests against her incarceration were observed in Cochabamba, La Paz, Santa Cruz, and Trinidad, constituting the largest mobilizations since the 2019 crisis. Meanwhile, opposition leaders denounced the processes against Áñez as "arbitrary" and accused the government of political persecution.[189] "This is not justice", said Mesa, "they are seeking to decapitate [the] opposition".[190] Doria Medina called her arrest a "dictatorial act", with similar statements being released by Camacho, Quiroga, and other major leaders.[191]

Preventative detention

.jpg.webp)

After being apprehended, Áñez was subsequently transferred to the Special Crime Fighting Force (FELCC) facilities in La Paz.[184] Around 9:00 a.m., she was referred to the Prosecutor's Office to take her statement but appealed to her right to silence because she did not have a lawyer. With that, she was returned to her cell at FELCC.[192] The Prosecutor's Office initially requested six months of preventative detention for Áñez, arguing that she presented a flight risk.[193] Judge Regina Santa Cruz of the Ninth Criminal Investigation Court of La Paz agreed with that assessment on the grounds that the former president had attempted to evade capture, was arrested at an address different than her own, and was discovered with packed suitcases. However, the judge determined to shorten the mandated pre-trial detention from six to four months while the investigation was underway.[194] Attorney General Wilfredo Chávez appealed the decision, stating that four months did not grant prosecutors sufficient time to investigate the coup d'état case.[195] On 20 March, the criminal chamber of the Departmental Court of Justice accepted the appeal and extended Áñez's detention to the requested six months.[196] On 3 August, a further six months were added, with the court again basing its decision on the potential flight risk that Áñez presented.[197] On 2 October, the main case against her was split into two separate processes, leading a judge to impose another five months of preventative detention.[198] This was extended by three months on 22 February 2022, totaling one year and eight months in detention without trial.[199] On 19 May, it was extended by a further three months.[200] France24 noted that at the current rate, Áñez's trial could last at least three years.[199]

After two days of detention in a FELCC cell, Áñez was transferred to the Obrajes Women's Orientation Center (COF) on 15 March, where she was set to carry out a mandatory period of fifteen days in isolation to comply with COVID-19 safety protocols.[194][201] However, at around 1:10 a.m. on 20 March, she was transferred from Obrajes prison to the Miraflores Women's Penitentiary.[202] The government assured that the Miraflores prison met "more optimal conditions" because it provided her a space separate from other prisoners, adequate access to healthcare, and the ability to receive visits from her family, as well as national and international delegations.[203]

Mental and physical health

A marked decline in Áñez's mental and physical well-being was observed during her detention. On 17 March, Áñez was examined by a prison doctor, who recorded that she was suffering from hypertension and that her arterial blood pressure registered at 190 mmHg, putting her at risk of stroke. Due to her state of health, Áñez's defense and family requested that she be transferred to the Clinica del Sur—located two blocks from the prison—for examination. Her lawyer, Luis Guillén, stated that the request had initially been authorized, but, "at the last minute", the Departmental Director of the Penitentiary Regime changed course and rejected it, instead bringing its own specialists to treat her.[204] A freedom action filed by Áñez's lawyers in order to transfer her to a public clinic was accepted by the Tenth Sentencing Court, but the decision was reversed upon appeal by the Prosecutor's Office, which requested that she be treated by personnel from the Institute of Forensic Investigations (IDIF)—dependent on the Prosecutor's Office—or by doctors from public hospitals transferred to the prison.[202][205] After visiting her in her cell, Amparo Carvajal, president of the Permanent Human Rights Assembly of Bolivia (APDHB), reported that Áñez was experiencing severe depression and suicidal thoughts. "She doesn't want to fight. ... No one could visit her, not even her family, only her lawyer", she said.[206]

On 19 April, after some delays, a personal doctor was admitted into the Miraflores prison to examine Áñez's state of health. It was recorded that Áñez was suffering from hyperventilation and fever syndrome and was undergoing stomach pains. According to the doctor, such ailments could result in a probable kidney complication if left untreated.[207] A later medical report determined that she had a urinary tract infection that necessitated urgent hospitalization. For this reason, her defense submitted an evacuation request for medical and humanitarian reasons, but the prison, citing staffing issues, refused to accept it.[208] Under pressure from the OHCHR, a judge ruled that Áñez would be allowed to be treated by a private doctor, but they would have to do so in the prison and not in a clinic.[209]

Shortly after her period of preventative detention was extended by six months, Áñez was briefly transferred to the Thorax Institute to undergo a cardiological check-up on 11 August.[210] An official medical report determined that she continued to suffer from hypertension and had depressive anxiety syndrome. As a result, two days later, the Second Anticorruption Court ordered that Áñez be allowed to leave prison in order to be transferred to the German Clinic to undergo a medical evaluation.[211] Instead, she was once again taken to the Thorax Institute, where a cardiological evaluation recommended by IDIF was carried out instead of the Doppler echocardiography that her family had requested.[212] On 18 August, Áñez was once again transferred to a hospital—the third time in two weeks—to undergo a thorax exam. Her lawyers decried that the trip had not been coordinated with her family.[213]

Suffering from increasingly severe depression, Áñez attempted to commit suicide on 21 August, slashing her lower arms.[214] She has likened the processes against her to the military dictatorship of Luis García Meza: "These are very dark times ..., jail has been imposed on anyone who raises their head, protests, or demands compliance with the law". She argued that instead of employing force of arms, "the MAS political elite" had co-opted the judiciary in order to persecute its opponents.[215]

Viewing her sentence to have already been decided, Áñez declared a hunger strike on 9 February 2022.[216] After eight days, her lawyers reported that she was suffering from paresthesia in the mouth, legs, and feet due to a lack of magnesium and potassium, and a decrease in sugar.[217] On 17 February, a virtual hearing for the cessation of her preventative detention was forced to be suspended until the twenty-first after Áñez began to decompensate. Her private doctor, Karim Hamdan, reported that the former president's health was "delicate". He explained that Áñez was in the initial stages of emaciation and dehydration.[218]

Due to her critical state of health, Áñez's defense filed a freedom action to secure her release for urgent medical treatment. This was accepted by a judge, who arranged her transfer to a hospital.[219] The news of Áñez's possible release provoked a mobilization of MAS-related groups, who gathered outside the Miraflores prison to prevent her exit. The protest devolved into violence when a vigil in support of Áñez was attacked, leading to multiple injuries, including Áñez's daughter, Carolina, who was left with a bruised eye and scratches on her face.[220] Within hours, the judge who authorized Áñez's release reversed his decision at the request of the prison's warden, who argued that the protests outside made it impossible to comply with the transfer request. Instead, the judge ordered that Áñez receive treatment from inside the prison.[221] After fifteen days without food, Áñez lifted her hunger strike on 24 February.[222]

During one of her last appearances before the court and sentence, on 9 June 2022, Áñez decompensated again and proceedings had to be suspended, leading to renewed condemnation of her treatment.[223]

Criminal processes

Coup I and coup II cases

The primary process against Áñez is the coup d'état case, in which she was initially accused of conspiracy, sedition, and terrorism. In May 2021, the Prosecutor's Office admitted a lawsuit by President of the Senate Andrónico Rodríguez, which expanded the case to include new processes against her for allegedly illegally assuming the presidency of the Senate in 2019. Her lawyers affirmed that Rodríguez's lawsuit covered the same crimes as the original case and thus should not have been included because it is illegal to judge an individual twice for the same action.[224]

The singular coup d'état case was split into two separate processes—labeled coup I and coup II—on 31 July. The coup I case—covering the conspiracy, sedition, and terrorism charges—was mired by difficulties due to the inability of prosecutors to gather the necessary testimonies. To date, only Mesa responded, only to affirm his right not to testify. The coup II case covers Rodríguez's complaint surrounding Áñez's succession to the presidency, for which she stands accused of resolutions contrary to the Constitution and laws and breach of duties.[2][225]

On 17 March 2022, the Plurinational Constitutional Court issued a ruling declaring the crime of sedition unconstitutional, thus leaving it "expelled from the Bolivian legal system". The decision came as a result of an action filed by former MAS parliamentarians in 2020, who requested that the crimes of sedition and terrorism be stricken from the Code of Criminal Procedure. At the time, the move was in response to the Áñez government's decision to charge former president Morales with those crimes.[226] By the time of the TCP's ruling, however, the decision was in benefit of Áñez. Nonetheless, Minister of Justice Iván Lima assured that the decision would not affect the processes against her, as she would continue to be prosecuted for the crimes of conspiracy and terrorism.[227]

Coup II trial

On 12 January 2022, Minister of Government Eduardo del Castillo announced that the first oral trial against Áñez for the coup II case would commence in the ensuing days. Guillén criticized that her defense had not been officially notified of this by the court prior to the announcement and pointed out that the Ministry of Government, as part of the executive branch, was not authorized to release official communications on behalf of the judiciary. He alleged that this "irregular, anomalous" action was a sign of government pressure on the courts to expedite the judicial process.[228][229] On 21 January, the official date of the trial was set for 9:00 a.m. on 10 February in a virtual courtroom using the Cisco Webex system.[230]

.jpg.webp)

Áñez's defense denounced the trial as "illegal", citing sixteen irregularities in the procedure leading up to it. In particular, the lawyers accused the judges of bias, stated that the set date was not in line with their allotted time to formulate Áñez's defense, and denounced interference by executive authorities within the Ministry of Government, Ministry of Justice, and Attorney General's Office into the investigation of the Prosecutor's Office, who they also regarded as "inquisitive".[231] Within hours of its opening, the First Anti-Corruption Sentencing Court of La Paz unanimously decided to annul the order to initiate the trial, citing technical difficulties.[232][233] Despite the defense's request that it be held in person, the trial was reinitiated virtually on 28 March. However, further technical difficulties quickly caused the hearing to become disorderly, with judges, lawyers, defendants, and witnesses speaking over one another. It was ultimately postponed after Áñez suffered an anxiety attack in her cell.[234] The trial was reinitiated virtually at 9:00 a.m. on 4 April and lasted more than twelve hours, analyzing and resolving procedural complaints made by the defense and the Attorney General's Office. Unlike in the previous two hearings, media outlets were barred from witnessing the proceedings, prompting the National Press Association to denounce violations of its constitutional right to access information of public interest.[235]

.jpg.webp)

On 19 April, the Court determined to exclude thirty-five of the forty-one pieces of evidence presented by Áñez's defense. Among the discarded documents were the Organization of American States' report on the results of the 2019 elections, the TCP's initial ruling on the constitutionality of Áñez's succession, and the Bolivian Episcopal Conference's official account detailing Church-mediated meetings preceding her arrival to power.[236]

Nearing the end of the trial, Áñez's defense filed an appeal of unconstitutionality of the process against her. Per court procedure, the pending motion barred any final sentence from being issued until it was resolved, leading the court to suspend the trial on 4 May. Prosecutor Omar Mejillones classified the appeal as dilatory because it also prevented final arguments from being presented until the hearing was reinstated.[237] Twenty-two days later, the TCP rejected Áñez's appeal, stating that the former president "did not meet the necessary requirements for a substantive analysis and pronouncement".[238] Given this, the defense countered with a petition for supplementation, asking that the court clarify its reasoning for not hearing the appeal.[239] The defense's request was rejected by the TCP shortly thereafter, paving the way for the trial to be resumed without further interruptions.[240]

Prior to the trial's reinstatement, the defense asked that Áñez be authorized to attend the proceedings in-person but was denied. On the other side, Prosecutor General Juan Lanchipa indicated that the Prosecutor's Office would seek a fifteen-year sentence against the former president. As the prosecution presented its final arguments, Áñez once again began suffering health problems, with medical staff stating that she was experiencing back fatigue. Given the imbalance in her health, the court deemed it necessary to declare the hearing in recess until the following day, allowing prison staff to conduct a medical review.[241] For her part, Áñez stated that she understood the "rush" to sentence her but asked that the judges consider her debilitated state of health.[242] The next day, the defense presented the court with a formal request for the cessation of Áñez's preventative detention, arguing that she presented no risk of absconding. The time spent analyzing the plea—which was ultimately rejected—led the court to extend the recess into the following day, delaying the trial for the second time in a row.[243][244]

Finally, without further delay, the trial reconvened on 8 June and concluded two days later. On 10 June 2022, the First Anti-Corruption Sentencing Court of La Paz sentenced found Áñez guilty of breach of duties and resolutions contrary to the Constitution. The former president was sentenced to ten years in the Miraflores Women's Penitentiary Center.[245] Both the defense and prosecutors announced that they would appeal the decision. Áñez's lawyers stated that they would seek her acquittal until "all the routes are exhausted", after which they would appeal to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights "where there ... [is] no political interference". On the other hand, the Prosecutor's Office stated that it would seek the full fifteen years originally requested.[246]

On 28 June 2022, Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro offered the government of Bolivia the possibility of granting Áñez political asylum in Brazil, to which the Bolivian government refused.[247][248]

In July 2023, the Bolivian judiciary upheld on appeal the 10-year sentence against Áñez.[249] Áñez's lawyers filed the last possible appeal to the Supreme Court of Justice (TSJ), with Áñez adding that if the TSJ refuses to hear her appeal, she will resort to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.[250]

Other processes

Two days after Áñez's arrest, the Ministry of Justice announced that it would present four additional liability trials separate from the coup d'état case to the Attorney General's Office.[251] On 24 March 2021, it accepted all four accusations. In the first case, Áñez—along with her minister of government, José Luis Parada, and the former president of the Central Bank of Bolivia, Guillermo Aponte—stood accused of having accepted a loan of $360 million from the International Monetary Fund that generated $5 million in interest. The fact was made effective through Supreme Decree N° 4277, which was considered unconstitutional because it circumvented the authorization of the Legislative Assembly, whose consent is necessary to approve such a loan according to Article 158 of the Constitution. For this, she was charged with resolutions contrary to the Constitution and laws, uneconomic conduct, and breach of duties. On 14 April, Áñez refrained from testifying in this case.[252][253][254]