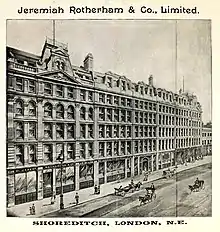

Jeremiah Rotherham & Co. was a department store in Shoreditch High Street, London, described during the early years as "Wholesale and Retail Drapers and General Warehousemen". The business evolved from a small drapery shop in the 1840s and grew to employ over 500 people.

In what appears to have been an altruistic gesture, the founder of the business, Jeremiah Rotherham (1806–1878), created a partnership with four of his long term employees. After his death they became the owners and sold the company via a stock market flotation in 1898. At this time the store was located at 81–91 Shoreditch High Street and 17–35 Boundary Street. Further expansion included the acquisition in 1935 of the London Theatre (formerly the Shoreditch Empire), 95–99 Shoreditch High Street, for use as warehouse space. During World War II the main store was hit by bombs during the London blitz; the company was able carry on trading by transferring to an adjacent building. In 1968 Jeremiah Rotherham & Co. was purchased by Spencer, Turner and Boldero,[1] later becoming part of the Dent Fownes/Dewhurst Dent P.L.C. group.[2]

Jeremiah Rotherham – founder

The founder of the store, Jeremiah Rotherham, was born in Whitwell, Derbyshire, England. He began his career as a haberdasher with his older brother, William Rotherham, who ran a linen drapers, haberdashers, silk mercers and furriers business at 39-41 Shoreditch High Street with John Hill Grinsell.[3] In 1832 the partnership between William Rotherham and Grinsell ceased[4] In 1835 William was declared bankrupt and on 1 February 1836 he was placed on trial at the Old Bailey for "Deception: bankruptcy: having been declared a bankrupt, feloniously did conceal part of his personal estate". He was found not guilty. The transcript of the trail provides insights into the size of his business operation and to the fact that another brother, Joseph (1810–1849), was working with him.[5]

By 1834 Jeremiah Rotherham had moved to a linen draper shop run by James Burrough (1764–1844),[6] at 84 Shoreditch High Street.[7] Burrough had two sons working for him, James (1795–c1844) and Joseph (1797–1826) who in 1824 had married Sophia Shingles (1794–1849) from Norfolk. They had one child before he died 1826. In 1834 the widowed Sophia married Jeremiah Rotherham: she was 40 and he was 28 years old.

When Burrough died in 1844, Rotherham took over the lease of his shop, where both he and Sophia worked and lived.[8] Sophia's sister, Mary Ann Shingles (1810–1849), lived with them, but in 1849, during the cholera epidemic that struck the East End in that year, Sophia died in August, followed within a month by Mary Ann.[9] They were both buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in Rotherham's family vault. Jeremiah's brother, Joseph Rotherham, who lived in Stepney, also died in the same year.

Another sister, Elizabeth Shingles (1788–1877), married the Norfolk schoolmaster George Boardman (1793–1876). One of their daughters, Marian Boardman (1824–1903), appears to have become a companion to Rotherham after his wife's death. She later married Rev. Frederic Halliley Stammers (1833–1902). She and her brother, Rev. Edward Hubbard Boardman (1826–1912), became major beneficiaries of Rotherham's will, inheriting his share of the business interests when he died in 1878.

Business partnerships

From about 1854 Jeremiah Rotherham took on business partners to help him run the store. The first was London-born fellow draper, George John Frederick Goodrich (1818–1885). He retired in 1875 for reasons of ill-health, by which time the store had expanded and included 81–87 Shoreditch High Street plus a new warehouse in Boundary Street.[10] The other partner at this time was Devon born draper, Robert Shapland (1826–1864). He helped to expand the wholesale side of the business, selling extensively to the millinery trade. Rotherham seemed genuinely fond of Shapland and his family; he was a witness at their wedding and the Shaplands named their third child Edgar Rotherham Shapman.[11]

The next partnership was set up with four employees who had worked their way up in the company. They were Frederick Snowden, George Gotelee, Robert Dummett and William Ellis.[12] Snowden (1844-1932) from Shoreditch, had started with the store in 1856 as an apprentice and later became Jeremiah Rotherham's private secretary. Gotelee (1840–1918), draper from Buckinghamshire, also started as a trainee at Rotherham's and later became a buyer. Ellis (1841–1924) was from Devon and described in the 1861 census as draper's assistant, later becoming a buyer. Dummett (1843–1907), also from Devon, began his career at Rotherham's in the dispatch department, eventually becoming the correspondence clerk and warehouse manager.[13]

Death of Jeremiah Rotherham

Rotherham died on 30 August 1878 in his Anlaby Houses, Upper Clapton, Hackney. His personal estate was valued in probate as under £350,000 (rough value today would be £41 million). He died childless and left the biggest part of his estate to his niece Marian (Boardman) Stammers (1824–1903) and nephew Rev. Edward Hubbard Boardman (1826–1912) in equal parts. Before his death, Rotherham had set up a partnership with Snowden, Gotelee, Dummett and Ellis. The instruction in his will was for his share of this partnership to become the property of his niece and nephew. They were at liberty to continue with the business or sell their interest, but he instructed that any sale must first be offered to Frederick Snowden. Rotherham made several other bequests in his will to charities and employees.[14] He also instructed his executors to provide for the continuation of a trust fund for the family of his former partner, Robert Shapland. Rotherham was buried in the family vault at Kensal Green Cemetery.

Anlaby

Jeremiah Rotherham had lived in Anlaby Houses, Upper Clapton for about 18 years. The house was one of a pair and leased by Rotherham. The other one of the pair was occupied by the Hubbard family who owned the freehold. The name Anlaby was later used by the company for a line of hosiery and for its 27–39 Boundary Street building, which has now been converted to a block of flats.[15] In his book Cracked Eggs and Chicken Soup: A Memoir of Growing Up Between The Wars, the author Norman Jacobs says that the use of the Anlaby name in the Rotherham business came about because they originally came from the Yorkshire town of that name.

Sale of store

In 1898 the four partners put the store up for sale for £500,000 via a stock market flotation. They agreed to stay on as directors to ensure a continuity of business arrangements and to liaise with stakeholders. At the time of Rotherham's death, several of the buildings in Shoreditch High Street appear to have been leased,[16] however by the time of the sale the company's property portfolio was said to be mostly freehold, including the main store in Shoreditch High Street, numbers 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 and 91, plus the building to the rear in Boundary Street, numbers 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 31, 33 and 35.[17] There is no mention in the prospectus of Rotherham's niece and nephew being involved in the sale of the store, so it appears that their interest in the business had been sold to the partners. Similar stock market flotation of privately owned department stores at this time included Harrods in 1889, William Whiteley (Universal Provider) in 1899 and D. H. Evans & Co in 1894. These stores were able to raise funding on the stock market for expansion and to purchase other smaller stores, for example Harrods purchased Dickins & Jones in 1914.[18] The application for shares in Jeremiah Rotherham & Co. was heavily oversubscribed and about two years later a further sale of debenture and ordinary shares was offered.[19] The dividend paid to shareholders for many years was between five and seven percent.[20]

The 600-page illustrated catalogue and general price list of 1904 details the variety of stock they carried in the store. There was also a mail order service on offer.[21]

Jeremiah Rotherham & Co dept. list, 1904 p1

Jeremiah Rotherham & Co dept. list, 1904 p1 Jeremiah Rotherham & Co dept. list, 1904 p2

Jeremiah Rotherham & Co dept. list, 1904 p2 Jeremiah Rotherham & Co dept. list, 1904 p3

Jeremiah Rotherham & Co dept. list, 1904 p3 Jeremiah Rotherham & Co dept. list, 1904 p4

Jeremiah Rotherham & Co dept. list, 1904 p4

Financial rewards

The four partners, Snowden, Dummett, Gotelee and Ellis, became wealthy from the sale of their business, but chose to remain as directors of the newly formed company. The most remarkable of them for long service was probably the chairman, Frederick Snowden, who retired on health grounds in 1926, having worked at the Rotherham store for 71 years.[22]

Robert Dummett died in 1907 aged 64 having been with Jeremiah Rotherham for 46 years. In his obituary it was said that he had left Devon at the age of 18 and travelled to London, without capital, without friends and without influence. He started at Rotherham's as an assistant in the despatch department and worked his way up to become head of the department. He died on 21 November 1907, and his probate indicates that he left £71,480, roughly equivalent to £8million today. His children included barrister, Sir Robert Ernest Dummett (1873–1941), who became chief magistrate, and George Herbert Dummett (1880–1969), silk/rayon merchant, whose son was philosopher Sir Michael Anthony Eardley Dummett.

George Gotelee died 18 September 1918 aged 78, having served with Rotherham’s for 62 years. His probate was recorded as £117,264. He was replaced on the board by Snowden's son, Frederick Sydney Snowden, who remained as a director until 1958. Gotelee's son, Sydney Treble Gotelee (1878-1959), later became a director, a position he retained until he retired in 1958.[23]

William Ellis died aged 84 on 11 March 1924 at his home in Reigate, Surrey leaving £178,616. He had been with Jeremiah Rotherham for about 64 years and regularly attended the AGMs up until his death, only missing the last meeting due to doctor's orders.[24] He had just one child, a daughter, Elizabeth Harriet Ellis (1872–1923), who married City broker Frank Ernest Doré (1867–1926). His family were the tailors, Doré and Sons, who had several shops in the City of London.[25]

When Jeremiah Rotherham died in 1878 he left his share of the business in equal measures to his niece, Marian (Boardman) Stammers, and nephew Rev. Edward Hubbard Boardman. They were at liberty to either continue as partners or to sell their interest to Frederick Snowden, and it appears they took the latter option. They were the children of Elizabeth Shingles (1788-1877) and George Boardman (1793-1876), who was a head teacher in Acle, Norfolk. After the death of Rotherham, the Rev Boardman, who was vicar of Grazeley, near Reading, resigned the living and moved to a large house called Glen Andred in Groombridge, East Sussex. He paid £7,200 for the house, which had formerly been the home of artist Edward William Cooke, and lived there with his wife in partial retirement until his death in 1912.[26] In his will he left £147,122 (rough equivalent today £17 million), with many large bequests to hospitals and charities.[27][28]

Marian (Boardman) Stammers, left £118,734 when she died in Brighton on 1 June 1903. She was married to Rev. Frederic Halliley Stammers (1833-1902) who was the incumbent minister at All Saints', Clapton in Hackney, an area of London where Jeremiah Rotherham had lived up until his death in 1878. The Stammers did not have children, but Rev. Stammers, who was a widower, had two children from his previous marriage and they were remembered by Rotherham with a legacy in his will. The Rev. Stammers' mother was Martha Halliley, from Dewsbury, Yorkshire. Her brother-in-law was Vicar John Buckworth of Dewsbury who had appointed Patrick Brontë as his curate in 1809.[29]

New management

After Frederick Snowden left the business in 1926, a new chairman was appointed. He was Joseph Hockley (1873–1954) who had trained as a draper and joined Jeremiah Rotherham & Co. in about 1894. He had been company secretary before becoming chairman, a position that he retained until his death in 1954, serving 60 years with the business. His tenure covered the difficult trading periods of the economic depression in the 1930s and the Second World War.[30]

London Music Hall

In 1933/34 the company purchased a theatre on an adjacent site located at 95–99 Shoreditch High Street. This was demolished to make way for a new warehouse. The theatre had various names during its history including: The Shoreditch Empire, Griffin Music Hall, The London Music Hall and London Theatre of Varieties. The frontage of the site was 117 ft, and the land area about 8000 sq feet.[31]

1941 bombing

In May 1941 the main store in Shoreditch High Street was destroyed by enemy bombing during World War II. The company was able to reopen for business by transferring trading to the new warehouse. Government compensation was received in 1950 for the damage to the building and further awards were made later for loss of stock, etc.[32]

Final years

By 1958 the financial position of the business was such that there was a call for the company to go into liquidation. In previous years, the policy had been to always appoint directors who had been employees of Jeremiah Rotherham & Co.[33] However, to save the business a compromise was agreed and Nadji Khazam (1910–1984), an outsider from the Anglo-African Finance group, was appointed as a director.[34][35] Khazam was originally from Iraq, and naturalised in Britain in about 1947.[36] He had worked in the textile industry for several years and during this time, he and his family had acquired controlling interest in several weaving companies belonging to Haighton Holdings. In 1951 he and his sister, Flora Yentob, sold these businesses to Aurochs Investment Company, although Khazam remained on as managing director.[37] By 1968 the Khazam family firm of Anglo-African Finance owned 49.5% of Jeremiah Rotherham, and they agreed to a takeover by rival company Spencer, Turner and Boldero.[38] In some respects this was more of a merger because Anglo-African Finance also had considerable interest in Spencer, Turner and Boldero.[39] Further rationalisation took place within the group of businesses run by the Khazam-Yentob family over the following years and evolved into Dewhurst Dent Limited.[40] The company still has members of both families on the board of directors.[41]

The Khazam-Yentob families had dealings in other sectors apart from textiles. In South Africa they were associated with companies that included automotive and mineral exploration.[42][43]

Flora (Khazam) Yentob was the mother of creative director Alan Yentob.[44]

References

- ↑ "£500,000 for J. Rotherham". The Guardian. 29 October 1968. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ↑ "Dewhurst Dent Limited". The Guardian. 28 May 1977. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ↑ "William Rotherham and John Hill Grinsell 39 Shoreditch linen draper". National Archives. MS 11936/507/1061071. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ↑ "Partnership dissolved". London Gazette (19006): 2795. 21 December 1832. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ↑ "William Rotherham. Deception: bankruptcy. 1st February 1836". The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674–1913. The University of Sheffield. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ↑ "James Burrough". Find a Grave. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ↑ "Insured: James Burrough and Jeremiah Rotherham, 86 Shoreditch, linen drapers". National Archive. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ↑ "Lease of 83-84 Shoreditch High Street". National Archives. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ↑ Farr, William (1852). Report on the Mortality of Cholera in England, 1848–49. London: HMSO. pp. 190–191. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ↑ "Partnership dissolved by mutual consent". The London Gazette (24280): 6690. 31 December 1875. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ↑ Partnership ended 1865

- ↑ Montagu, Williams (1896). Round London Down East And Up West. London: Macmillian. p. 32. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ↑ Barrier Miner, Sat 21 Dec 1895, Page 6, THE WAY TO SUCCESS – The Rotherhams of Shoreditch

- ↑ "Wills and Bequests". The Bury and Norwich Post. 15 October 1878. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ↑ Anlaby House, 27–39 Boundary Street, London E2 Heritage Statement, Revision A. 3 November 2010 Delta Architects page 9

- ↑ Ralph Fordham's properties in Shoreditch, Hackney Archives

- ↑ "Subscription List". The Pall Mall Gazette. 25 June 1898. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "Harrod's Stores Limited". The Times. 18 May 1914. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ "Jeremiah Rotherham and Company". The Morning Post. 11 December 1900. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ↑ De Montmorency, James Edward Geoffrey; Dicksee, Lawrence Robert (1903). Advanced accounting. London: Gee & Co. p. 254. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ↑ The General Price List. Shoreditch London: Jeremiah Rotherham & Co. 1904. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ↑ "Jeremiah Rotherham And Co." Times, 24 Feb. 1927, p. 20. The Times Digital Archive, Accessed 29 May 2019.

- ↑ "New Board for Jeremiah Rotherham". The Guardian. 24 September 1958. p. 10. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Jeremiah Rotherham And Company." Times, 27 Feb. 1924, p. 20. The Times Digital Archive, Accessed 12 June 2019

- ↑ Frank Ernest Dore stockbroker

- ↑ GLEN ANDRED: A GRADE II* GARDEN Sussex Gardens Trust

- ↑ The Times London, Greater London, England 25 May 1912, Sat Page 11

- ↑ Kent & Sussex Courier - Friday 3 May 1912, Rev. Canon H. C. Foster: The late Rev E. H. Boardman.

- ↑ "Patrick Bronte". Dewsbury Minster. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ↑ "Jeremiah Rotherham & Co". The Guardian. 1 April 1954. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ↑ Satisfactory turnover The Guardian London, Greater London, England, 28 Feb 1935, Thu • Page 14

- ↑ Company meeting The Guardian London, Greater London, England,28 Mar 1950, Tue. Page 9

- ↑ "Jeremiah Rotherham and Company". Manchester Guardian. 3 April 1947. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ↑ "More competition from U.S. banks in Europe." Dual Coupon Convertabe. Times, 22 Feb. 1967, p. 13. The Times Digital Archive, Accessed 29 June 2019.

- ↑ "Appontment of new directors and compromise to avoid liquidation". The Guardian. 24 September 1958. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ↑ "Naturalisation Certificate: Nadji Khazam. From Iraq". The National Archive. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ↑ "Haighton Holdings Limited". The Guardian. 15 November 1951. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ↑ "£500,000 for J. Rotherham". The Guardian London. 29 October 1968. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ↑ "Spencer, Turner & Boldero and Jeremiah Rotherham". The Guardian. 24 January 1967. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ↑ "Dewhurst Dent Limited". The Guardian. 28 May 1977. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ↑ "Dewhurst Dent P.L.C". Endole - Company Credit Reports. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ↑ Don Wilkinson Local takeover of Khazam Yentob group rumoured The Citizen, Johannesburg, DTIC ADA346221: Sub-Saharan Africa Report, No. 2830, P.111' 28 June 1983

- ↑ "Capital Gold and Exploration Company Limited" (PDF). South African Government Gazette. CXCVIII (6334): 25. 18 December 1959. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ↑ Yentob, Alan. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U41305.