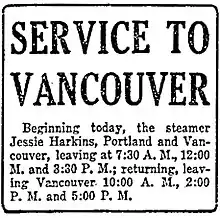

Steamers Jessie Harkins (on left) and Ione (on right) somewhere on the Columbia or Willamette Rivers, circa 1915 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Jessie Harkins (1903–1920); Pearl (1920–1958) |

| Owner | As Jessie Harkins: Harkins Trans. Co.; as Butterfly: Harry Young and A.D. Chase; as Pearl: Shaver Trans. Co. |

| Route | Lower Columbia and Willamette rivers |

| In service | 1903 |

| Out of service | 1958 |

| Identification | U.S. ## 200443 (1905–1909); 206018 (1909–1958) |

| Fate | Broken up |

| Notes | Rebuilt in 1909; original hull used to construct steamer Butterfly |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | inland passenger and light freight |

| Tonnage | 88 GT; 74 RT(1909-) |

| Length | 72 ft (21.95 m) (1903–1909); 88 ft (26.82 m) (1909–1958) |

| Beam | 13.5 ft (4.11 m) (1903–1909):15.5 ft (4.72 m)(1909–1958) |

| Depth | 5.0 ft (1.52 m) (1909–1958) depth of hold |

| Installed power | gasoline (1903–1905); steam (1905–1925); diesel (1925–1958) |

| Propulsion | propeller |

| Capacity | 90 to 100 passengers |

Jessie Harkins was a propeller-driven steamboat that operated on the Columbia River in the USA starting in 1903. It was rebuilt at least twice. Originally, Jessie Harkins was one of the larger gasoline-engined vessels to operate on the Columbia River.[1] Jessie Harkins was built for the Harkins Transportation Company.

In 1905, Jessie Harkins was somewhat enlarged, and converted from gasoline to steam engine power.[2]

In 1909, Jessie Harkins was again reconstructed and the components were used to build two new vessels. The cabin structure (called the "house") of the original vessel was removed, and installed on a newly built hull.[3] This boat kept the name Jessie Harkins, but was assigned a new official merchant vessel identification number, 206018. This new boat was larger than the one built in 1903.

The old hull from the 1903 boat was sold to another company, which built a new cabin structure on the hull, and operated the boat for about six months in 1909 under the name Butterfly[3] Butterfly somewhat confusingly kept the original merchant vessel identification number as the 1903 Jessie Harkins, which was 200443.[3] Butterfly was once mistaken in the contemporary press as Jessie Harkins.[4]

The numerous small craft like Jessie Harkins that operated on the Columbia and the Willamette Rivers were sometimes referred to as the "mosquito fleet".[5]

In 1920, Harkins Transportation Co. sold Jessie Harkins to the Shaver Transportation Company, which renamed the boat Pearl. In 1925, Shaver Transportation Co. converted Pearl to diesel power. Shaver Transportation operated Pearl for a long time as a towboat, eventually dismantling it in the 1950s.

Name

Jessie Harms was named after the daughter of a prominent Oregon riverboat family, who later married a New York towboat operator, Harry Van Aults.[6]

Construction

Jessie Harkins was built at the Portland Shipbuilding Company for Captain Hosford and launched on November 18, 1903.[1] Jessie Harkins was powered by a 45 horsepower gasoline engine, and was one of the largest of these types of vessels to be launched on the Columbia River.[1]

Jessie Harkins was built for the run between Vancouver and Washougal, Washington. It was not intended to carry freight or baggage, but passengers only, and running on day trips only, it had no overnight passenger accommodations.Passenger capacity was about 100 for every trip.[1]

Jessie Harkins was 72 ft (21.95 m) long and had beam of 13.5 ft (4.11 m).[1] The boat was owned by the Hosford brothers.[7]

Career of Jessie Harkins before 1909 rebuild

Portland–St. Johns route

On May 6, 1904, it was announced that Jessie Harkins would be put on a route running on the lower Willamette river from Portland to St. Johns, Oregon.[7] The boat made six round trips a day, leaving the Washington Street dock in Portland at 7:00, 8:30 and 10:30 a.m, and 1:00, 2:30 and 4:00 p.m.[7] The downstream run took 30 minutes.[7] The fare was five cents to the dry dock on the Willamette River and 10 cents to Linnton further downstream.[7]

1905 reconstruction

On Saturday, April 8, 1905, it was reported that the following Monday, April 10, Jessie Harkins would be placed on a new route, running from Portland to Washougal.[2] Jessie Harkins was reported to have been enlarged and equipped with steam machinery.[2]

The re-engined boat was to have been taken on a trial run on April 7, 1905, with the new machinery. Jessie Harkins would take up the schedule of Ione, departing Washougal at 7:00 a.m. for Portland, and leaving Portland for Washougal at 2:00 p.m. The boat would carry passengers only on this route.[2]

In 1906, the official merchant vessel registry number was 200443.[8]

1909 reconstruction

The Harkins line had Jessie Harkins reconstructed at Vancouver, Washington, in 1909 and placed in service on a route between Portland and Camas and Washougal.[9] The rebuilt Jessie Harkins was 88 ft (26.82 m) long with a beam of 15.5 ft (4.72 m) feet, depth of hold of 5.0 ft (1.52 m) feet, with an overall size of 88 gross tons (a unit of volume and not weight) and 74 registered tons.[9][10] The boat had a new official merchant number, 206018.[11]

A permanent steamboat license was issued to Jessie Harkins on the afternoon of March 9, 1909, for the run between Portland and Camas and Washougal.[10] Jessie Harkins had a legal limit of 90 passengers in 1910.[12]

Career of Butterfly

Reconstruction from old hull of Jessie Harkins

Harry Young and A.D. Chase bought the old hull of Jessie Harkins from Captain Hosford with the intent to equip it for service on the Willamette and Columbia rivers.[3] Young and Chase intended to install engines and a boiler on the old hull and operate it under the name Butterfly, keeping the old official merchant vessel registry number of Jessie Harkins, 200443.[13][3] The work was to be done at the Supple yards and was expected to take about six weeks.[3]

1909 operations

Butterfly was in fact completed.[14] In September 1909, Butterfly was placed on the route along Multnomah Channel, then called Willamette Slough, from Portland to St. Helens, Oregon[15]

Destruction by fire

On November 3, 1909, Butterfly's cabins burned completely while wooding up at Martins Bluff.[16][5] This put the steamer out of service for a long time, although the hull and machinery were essentially still sound. On March 1911, the hull was at the east bank on the Willamette north of the approach to the first Burnside Bridge, when there was talk of its being sold and built into a boat to run somewhere on the Oregon coast.[17]

Return to service

In early April 1913 Butterfly, then owned by Anderson, Crowe & Co., was sold to the Albina Fuel Company for $1,500 to be used in towing work.[18] After the sale, Butterfly was taken to be hauled out at the St. Johns Shipbuilding Company to be overhauled and to have the cabin structure rebuilt.[18]

Sunk at mooring

In early October 1920, Butterfly sank at is moorings in Portland.[19] The boat was raised on October 8, 1920, with the use of two derrick scows, and lines passed under the hull by master diver Fred de Rock.[19]

Career of Jessie Harkins 1909–1920

On July 1, 1909, driftwood fouled the paddle wheel of the steam ferry Lionel R. Webster, operating on the Willamette River, carrying away a number of paddle buckets and leaving the ferry in a disabled condition.[20] Webster hailed Harkins, which was passing by, and Harkins was able to tow the ferry back to its slip on the west side of the Willamette.[20]

Merger with Ione

In the first part of 1910 Jessie Harkins was competing with Ione on the Portland-Washougal route.[21] In early June 1910 this competition ended when the owners of Harkins and Ione agreed to operate from the same dock and use the same agent in Washougal, with Harkins continuing to depart for Portland in the afternoon, with Ione shifting to the morning run.[21]

New boiler

Harkins was withdrawn from service in February 1911 to have a new boiler installed at Willamette Iron and Steel Works, after which the boat would undergo a general overhaul at the Supple yard in Portland.[22] Jessie Harkins was returned to service on February 15, 1911.[23]

Casualties

Passenger drowns

On December 29, 1910, George Steenson drowned when he attempted to jump from Jessie Harkins on to the dock at Ellsworth, Washington.[24] Harkins, running under Captain Hosford, had pulled away from the dock, then returned to make a second landing. As the boat was pulling away a second time, Steenson said he wanted to get off the boat and jumped for the dock, but missed and fell in the water. The steamer's lifeboat was launched but no trace of Steenson could be found. It was initially that possible thought he might have reached shore, as he was reported to have been a good swimmer.[24]

Deckhand drowns

On March 23, 1911, a deckhand named Miller on Jessie Harkins fell overboard at Vancouver as he was pulling on a box of fish, and drowned.[25] On May 6, 1911, Clark County Sheriff Ira C. Cresap and A.J. Templeton, deputy coroner found a body at Mercer's Island, five miles downriver from Vancouver, which they believe to be that of Miller.[25][26][27]

Rowboat swamped

In January 1917, waves from the wake of the passing Jessie Harkins swamped a rowboat laden with scrap iron and occupied by four young men. All four occupants of the boat were thrown into the river. Three were rescued by the sternwheeler Weown which had been proceeding behind Jessie Harkins. The fourth man, Anthony Ambrose, however was drowned.[28]

Ambrose, who was survived by an aged mother whom he had supported, had been a boilermaker, but had been unemployed for some time. He and his companions had pried off the iron from an old burned dock and were taking it to the Albina ferry slip to sell.[28]

Ice problems

Winter ice often created navigation issues on the Columbia, especially for smaller vessels like Jessie Harkins. In early January 1912, the Columbia River was frozen over as far downstream as Vancouver, forcing Jessie Harkins, which had been operating across the river in the place of the side-wheel ferry City of Vancouver, to abandon the ferry route. Jessie Harkins, running under Captain Hosford, was then taken to Portland, where work was done to sheath the forward part of the hull with galvanized iron to improve ice-breaking capabilities of the boat. After that Jessie Harkins would carry freight and passengers as far as the mouth of the Willamette so long as the icy conditions prevailed that season on the Columbia River.[29]

Ferry work

Jessie Harkins was often used as a standby ferry on the route across the Columbia River between Hayden Island on the south side, and Vancouver Washington, on the north shore. Unlike the regular ferry, Jessie Harkins had no capacity for the transport of automobiles or carriages.[30]

Jessie Harkins had also provided ferry service to settlers on the now uninhabited Government Island.[31]

In May 1911 Jessie Harkins was employed to transport passengers across the Columbia river from Vancouver to the terminus, on Hayden Island, of the Portland Railway, Light and Power Company, which promised overland rail service from there to Portland in 25 minutes, as opposed to the 40 minutes that it had taken for many years previously.[32]

Sale to Shaver Transportation Company

The construction of good highways ended the utility of Jessie Harkins as a passenger and light freight ferry.[6]

In February 1920, the Harkins line sold Jessie Harkins to Shaver Transportation Company for use as a towboat.[33] For several years before the sale Harkins Transportation Company had been running Jessie Harkins on a freight route between Portland and Camas and Washougal.[33] This route was discontinued after the sale of Jessie Harkins, as was ferry service to government island.[33]

Residents of Government Island sought county assistance to fund a replacement ferry, but the county commissioners said they had no funds to do so.[31]

Shaver Transportation renamed Jessie Harkins as Pearl, after Pearl Shaver Hoyt, a daughter (or sister) of George Washington Shaver, the founder of Shaver Transportation Co.[6][34]

Five years later Shaver Transportation converted Pearl to diesel power.[6] The diesel engine produced 200 horsepower. The conversion was done for work on the Clark & Wilson Lumber Company's log booms on Multnomah Channel.[35]

Pearl was the first boat commanded by Leonard R. Shaver Sr., who by 1955 had become the president of the Shaver concern.[6]

Disposition

In 1955, it was reported that Shaver Transportation intended to dismantle the upper works of Pearl and burned its hull as part of its effort to convert its fleet to steel-hulled vessels.[6] At the time Pearl was 84 feet long.

Another report is that Pearl was dismantled in 1958.[36]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 H.W. Scott, ed. (November 19, 1903), "Jessie Harkins Launched – Hosford's Gasoline Steamer Ready for Service", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H. L. Pittock, vol. 43, no. 13, 398, 5, col.3

- 1 2 3 4 H.W. Scott, ed. (April 8, 1905), "Goes On Her New Route – Steamer Jessie Harkins Will Begin Service Monday", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 45, no. 13, 832, 7, col.5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 H.W. Scott, ed. (May 30, 1909), "Purchase Hull of Old Jessie Harkins", Sunday Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 37, no. 22, 9, col.3

- ↑ H.W. Scott, ed. (July 30, 1909), "Jessie Harkins on New Route", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 49, no. 15, 186, 18, col.1

- 1 2 E.B. Piper, ed. (April 3, 1913), "Steamer Butterfly Sold – Craft to Be Recommissioned After Idleness of Three Years", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 53, no. 16, 336, 18, col.3

- H.W. Scott, ed. (July 24, 1905), "Rowboat is Run Down By Launch – Three Are Thrown Into the Water as Result of Accident", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 45, no. 13, 923, 9, col

- E.D. Piper, ed. (September 17, 1913), "Small Craft Being Repaired -- Etna Being Rehabilitated and Eva Is Due for Overhauling", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 53, no. 16, 478, 18, col.4 - 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Shaver Tugs Face Torch", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR, vol. 95, no. 29, 540, 15, col.2, July 9, 1955

- 1 2 3 4 5 H.W. Scott, ed. (May 6, 1904), "New Steamboat Service", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 43, no. 13, 543, 12, col.3

- ↑ U.S. Treasury Dept, Statistics Bureau (1907). Annual List of Merchant Vessels (FY end June 30, 1906). Vol. 38. Wash. DC: GPO. 246. hdl:2027/uc1.b3330070.

- 1 2 Newell, Gordon R., ed. (1966). "Maritime Events of 1909". H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, Washington: Superior Pub. Co. 162. LCCN 66025424.

- 1 2 H.W. Scott, ed. (March 10, 1909), "Papers Issued to Harkings", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 49, no. 15, 064, 14, col.1

- ↑ U.S. Treasury Dept, Statistics Bureau (1912). Annual List of Merchant Vessels (FY end Jun 30, 1911). Vol. 43. Wash. DC: GPO. 217.

- ↑ H.W. Scott, ed. (July 5, 1910), "Crowds Seek Quietude on Steamers and Nooks Far from Celebration's Din", Morning Oregonian (photo caption), Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 50, no. 15, 477, 21, cols.2–4

- ↑ U.S. Treasury Dept, Statistics Bureau (1912). Annual List of Merchant Vessels (FY end Jun 30, 1911). Vol. 43. Wash. DC: GPO.

- ↑ U.S. Treasury Dept, Statistics Bureau (1912). Annual List of Merchant Vessels (FY end Jun 30, 1911). Vol. 43. Wash. DC: GPO. 143.

- ↑ H.W. Scott, ed. (September 24, 1909), "Butterfly Goes on Slough Run", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, 18, col.4

- ↑ H.W. Scott, ed. (November 5, 1909), "Butterfly Burns at Martins Bluff", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 49, no. 15, 270, 22, cols.1–2

- "Order Two Investigations – Local Inspectors to Take Testimony in Butterfly and Robinson Cases", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 49, no. 15, 274, 18, col.1, November 10, 1909 - ↑ E.B. Piper, ed. (March 10, 1911), "Marine Notes", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 51, no. 15, 690, 9, col.2

- 1 2 E.B. Piper, ed. (April 3, 1913), "Steamer Butterfly Sold – Craft to Be Recommissioned After Idleness of Three Years", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 53, no. 16, 336, 18, p.3

- 1 2 E.B. Piper, ed. (October 8, 1920), "Submerged Steamer Raised – Little River Craft Butterfly Is Lifted With Aid of Diver", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR, vol. 59, no. 18, 681, 18, col.3

- 1 2 H.W. Scott, ed. (July 2, 1909), "Lionel R. Webster Disabled", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 49, no. 15, 162, 18, col.3

- * Mills, Randall V. (1947). "Appendix A: Steamers of the Columbia River System". Sternwheelers up Columbia -- A Century of Steamboating in the Oregon Country. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska. 191. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7. LCCN 77007161. - 1 2 H.W. Scott, ed. (June 5, 1910), "Opposition Lines in Truce", Sunday Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 29, no. 23, 10, col.3

- ↑ E.B. Piper, ed. (February 4, 1911), "Marine Notes", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 51, no. 15, 661, 22, col.4

- ↑ E.B. Piper, ed. (February 16, 1911), "Marine Notes", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 51, no. 15, 671, 18, col.2

- 1 2 E.B. Piper, ed. (December 30, 1910), "Body Cannot Be Found – George Stinson Jumps From Steamer and Probably Drowns", Morning Oregonian (Dateline: Washougal, Wash., Dec. 29 (Special)), Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 50, no. 15, 630, 5, col.1

- 1 2 E.B. Piper, ed. (May 7, 1911), "Body Found Floating in River", Morning Oregonian (Dateline: Vancouver, Wash., May 7 (Special).), Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 51, no. 15, 740, 3, col

- ↑ McKay, David. "History of the Office". Clark County Washington Sheriff. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ↑ Jollota, Pat (February 2012), "First Boom and Bust", Legendary Locals of Vancouver, Washington, Arcadia, 43, ISBN 9781467100014

- 1 2 E.B. Piper, ed. (January 18, 1917), "A. Ambrose Is Drowned – Waves From Steamer Swamp Row-Boat Laden With Iron – Three Companions Rescued by Crew of Steamer Weownd – Body of Victim Recovered in Short Time", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 56, no. 17, 522, 20, cols.1–2

- ↑ E.B. Piper, ed. (January 9, 1912), "Forbidding River Worries Skippers – Rise of 14.9 Feet Recorded in Lower Columbia Within Period of 24 Hours – Drift Clutters Stream – That Willamette's Crest Is High on Banks Indicated by Debria Floating Towards Pacific – Ice Floes Are Heavy", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 51, no. 15, 951, 16, col.1

- ↑ E.B. Piper, ed. (April 24, 1913), "Auto Trip Is Abandoned -- Vancouver Woman's Club Members Forget Ferry's Night Off", Morning Oregonian (Dateline: Vancouver, Wash., April 23. (Special).), Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 53, no. 16, 354, 6, col.3

- 1 2 E.B. Piper, ed. (February 15, 1921), "Island Ferry Is Denied – County Commission Pleads Funds Are Lacking – Produce That Should Come to Local Market Will Be Shipped to Seattle, Say Growers", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR, vol. 60, no. 18, 794, 9, col.3

- ↑ E.B. Piper, ed. (May 21, 1911), "25-Minute Cars Planned – Railway Promises to Improve Vancouver-Portland Run", Sunday Oregonian (Dateline: Vancouver, Wash., May 20 (Special).), Portland, OR: H.L. Pittock, vol. 30, no. 21, 5, col.3

- 1 2 3 E.B. Piper, ed. (February 13, 1920), "River Freighter Sold", Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR, vol. 59, no. 18, 477, 22, col.2

- ↑ Newell, Gordon R., ed. (1966). "Marine Events of 1920". H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, Washington: Superior Pub. Co. 304. LCCN 66025424.

- ↑ Newell, Gordon R., ed. (1966). "Maritime Events of 1925". H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, Washington: Superior Pub. Co. 367. LCCN 66025424.

- ↑ Newell, Gordon R., ed. (1966). "Maritime Events of 1958". H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, Washington: Superior Pub. Co. 631. LCCN 66025424.

References

Printed sources

- Mills, Randall V. (1947). Sternwheelers up Columbia -- A Century of Steamboating in the Oregon Country. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7. LCCN 77007161.

- Newell, Gordon R., ed. (1966). H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, Washington: Superior Pub. Co. LCCN 66025424.

On-line newspapers and journals

- "Historic Oregon Newspapers". University of Oregon.

- "The Historical Oregonian (1861–1987)". Multnomah County Library.