Joan Miró | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Carl Van Vechten, 1935 | |

| Born | Joan Miró i Ferrà 20 April 1893 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain |

| Died | 25 December 1983 (aged 90) Palma, Mallorca, Spain |

| Education | Escola de Belles Arts de la Lotja and Escola d'Arte de Francesc Galí, Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc, 1907–1913 |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, mural and ceramics |

| Movement | Surrealism |

| Spouse |

Pilar Juncosa Iglésias

(m. 1929) |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Joan Miró i Ferrà (/mɪˈroʊ/ mi-ROH,[1] US also /miːˈroʊ/ mee-ROH,[2][3] Catalan: [ʒuˈam miˈɾoj fəˈra]; 20 April 1893 – 25 December 1983) was a Spanish painter, sculptor and ceramist born in Barcelona. Professionally, he was simply known as Joan Miró. A museum dedicated to his work, the Fundació Joan Miró, was established in his native city of Barcelona in 1975, and another, the Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró, was established in his adoptive city of Palma in 1981.

Earning international acclaim, his work has been interpreted as Surrealism but with a personal style, sometimes also veering into Fauvism and Expressionism.[4] He was notable for his interest in the unconscious or the subconscious mind, reflected in his re-creation of the childlike. His difficult-to-classify works also had a manifestation of Catalan pride. In numerous interviews dating from the 1930s onwards, Miró expressed contempt for conventional painting methods as a way of supporting bourgeois society, and declared an "assassination of painting" in favour of upsetting the visual elements of established painting.[5]

Biography

Born into a family of a goldsmith and a watchmaker, Miró grew up in the Barri Gòtic neighborhood of Barcelona.[6] The Miró surname indicates some possible Jewish roots (in terms of marrano or converso Iberian Jews who converted to Christianity).[7][8] His father was Miquel Miró Adzerias and his mother was Dolores Ferrà.[9] He began drawing classes at the age of seven at a private school at Carrer del Regomir 13, a medieval mansion. To the dismay of his father, he enrolled at the fine art academy at La Llotja in 1907. He studied at the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc[10] and he had his first solo show in 1918 at the Galeries Dalmau,[11] where his work was ridiculed and defaced.[12] Inspired by Fauve and Cubist exhibitions in Barcelona and abroad, Miró was drawn towards the arts community that was gathering in Montparnasse and in 1920 moved to Paris, but continued to spend his summers in Catalonia.[6][13][14][15]

Career

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_65_x_73_cm%252C_Museo_Nacional_Centro_de_Arte_Reina_Sof%C3%ADa.jpg.webp)

Miró initially went to business school as well as art school. He began his working career as a clerk when he was a teenager, although he abandoned the business world completely for art after suffering a nervous breakdown.[18] His early art, like that of the similarly influenced Fauves and Cubists, was inspired by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne. The resemblance of Miró's work to that of the intermediate generation of the avant-garde has led scholars to dub this period his Catalan Fauvist period.[19]

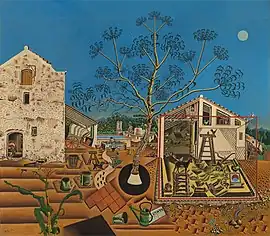

A few years after Miró's 1918 Barcelona solo exhibition,[11] he settled in Paris where he finished a number of paintings that he had begun on his parents' summer home and farm in Mont-roig del Camp. One such painting, The Farm, showed a transition to a more individual style of painting and certain nationalistic qualities. Ernest Hemingway, who later purchased the piece, described it by saying, "It has in it all that you feel about Spain when you are there and all that you feel when you are away and cannot go there. No one else has been able to paint these two very opposing things."[20] Miró annually returned to Mont-roig and developed a symbolism and nationalism that would stick with him throughout his career. Two of Miró's first works classified as Surrealist, Catalan Landscape (The Hunter) and The Tilled Field,[21] employ the symbolic language that was to dominate the art of the next decade.[22]

Josep Dalmau arranged Miró's first Parisian solo exhibition, at Galerie la Licorne in 1921.[13][23][24]

In 1924, Miró joined the Surrealist group. The already symbolic and poetic nature of Miró's work, as well as the dualities and contradictions inherent to it, fit well within the context of dream-like automatism espoused by the group. Much of Miró's work lost the cluttered chaotic lack of focus that had defined his work thus far, and he experimented with collage and the process of painting within his work so as to reject the framing that traditional painting provided. This antagonistic attitude towards painting manifested itself when Miró referred to his work in 1924 ambiguously as "x" in a letter to poet friend Michel Leiris.[25] The paintings that came out of this period were eventually dubbed Miró's dream paintings.

Miró did not completely abandon subject matter, though. Despite the Surrealist automatic techniques that he employed extensively in the 1920s, sketches show that his work was often the result of a methodical process. Miró's work rarely dipped into non-objectivity, maintaining a symbolic, schematic language. This was perhaps most prominent in the repeated Head of a Catalan Peasant series of 1924 to 1925. In 1926, he collaborated with Max Ernst on designs for ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev.

Miró returned to a more representational form of painting with The Dutch Interiors of 1928. Crafted after works by Hendrik Martenszoon Sorgh and Jan Steen seen as postcard reproductions, the paintings reveal the influence of a trip to Holland taken by the artist.[27] These paintings share more in common with Tilled Field or Harlequin's Carnival than with the minimalistic dream paintings produced a few years earlier.

Miró married Pilar Juncosa in Palma (Majorca) on 12 October 1929. Their daughter, María Dolores Miró, was born on 17 July 1930. In 1931, Pierre Matisse opened an art gallery in New York City. The Pierre Matisse Gallery (which existed until Matisse's death in 1989) became an influential part of the Modern art movement in America. From the outset Matisse represented Joan Miró and introduced his work to the United States market by frequently exhibiting Miró's work in New York.[28][29]

In 1932 he created a scenic design for Massine's ballet Jeux d'enfants at Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo.

Until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Miró habitually returned to Spain in the summers. Once the war began, he was unable to return home. Unlike many of his surrealist contemporaries, Miró had previously preferred to stay away from explicitly political commentary in his work. Though a sense of (Catalan) nationalism pervaded his earliest surreal landscapes and Head of a Catalan Peasant, it was not until Spain's Republican government commissioned him to paint the mural The Reaper, for the Spanish Republican Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exhibition, that Miró's work took on a politically charged meaning.[30]

In 1939, with Germany's invasion of France looming, Miró relocated to Varengeville in Normandy, and on 20 May of the following year, as Germans invaded Paris, he narrowly fled to Spain (now controlled by Francisco Franco) for the duration of the Vichy Regime's rule.[31] In Varengeville, Palma, and Mont-roig, between 1940 and 1941, Miró created the twenty-three gouache series Constellations. Revolving around celestial symbolism, Constellations earned the artist praise from André Breton, who seventeen years later wrote a series of poems, named after and inspired by Miró's series.[32] Features of this work revealed a shifting focus to the subjects of women, birds, and the moon, which would dominate his iconography for much of the rest of his career.

Shuzo Takiguchi published the first monograph on Miró in 1940. In 1948–49 Miró lived in Barcelona and made frequent visits to Paris to work on printing techniques at the Mourlot Studios and the Atelier Lacourière. He developed a close relationship with Fernand Mourlot and that resulted in the production of over one thousand different lithographic editions.

In 1959, André Breton asked Miró to represent Spain in The Homage to Surrealism exhibition alongside Enrique Tábara, Salvador Dalí, and Eugenio Granell. Miró created a series of sculptures and ceramics for the garden of the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, which was completed in 1964.

In 1974, Miró created a tapestry for the World Trade Center in New York City together with the Catalan artist Josep Royo. He had initially refused to do a tapestry, then he learned the craft from Royo and the two artists produced several works together. His World Trade Center Tapestry was displayed at the building[33] and was one of the most expensive works of art lost during the September 11 attacks.[34][35]

In 1977, Miró and Royo finished a tapestry to be exhibited in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.[36][37]

In 1981, Miró's The Sun, the Moon and One Star—later renamed Miró's Chicago—was unveiled. This large, mixed media sculpture is situated outdoors in the downtown Loop area of Chicago, across the street from another large public sculpture, the Chicago Picasso. Miró had created a bronze model of The Sun, the Moon and One Star in 1967. The maquette now resides in the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Late life and death

In 1979 Miró received a doctorate honoris causa from the University of Barcelona. The artist, who suffered from heart failure, died in his home in Palma (Majorca) on 25 December 1983 at age 90.[38] He was later interred in the Montjuïc Cemetery in Barcelona.

Mental health

It has been established through the analysis of personal texts written by Joan Miró that he has experienced multiple episodes of depression throughout his life.[39] He experienced his first depression when he was 18 in 1911.[40] Much of the literature refers to this as if it was a small setback in his life, while it appeared to be much more than that.[41] Miró himself stated: I was demoralized and suffered from a serious depression. I fell really ill, and stayed three months in bed.[42]

There is a clear connection between his mental health and his paintings, since he used painting as a way of dealing with his episodes of depression. It supposedly even made him more calm and his thoughts less dark. Joan Miró said that without painting he became very depressed, gloomy and I get 'black ideas', and I do not know what to do with myself.[43]

The influence of his mental state is very well visible in his painting Carnival of the Harlequin. He tried to paint the chaos he experienced in his mind, the desperation of wanting to leave that chaos behind and the pain created because of that. Miró painted the symbol of the ladder here which is also visible in multiple other paintings after this painting. It is supposed to symbolize escaping.[44]

The relation between creativity and mental illness is very well studied.[45] Creative people have higher chances of suffering from a manic depressive illness or schizophrenia, as well as higher chance to transmit this genetically.[46] Even though we know Miró suffered from episodic depression, it is uncertain whether he also experienced manic episodes, which is often referred to as bipolar disorder.[47]

Works

Early fauvist

His early modernist works include Portrait of Vincent Nubiola (1917), Siurana (the path), Nord-Sud (1917) and Painting of Toledo. These works show the influence of Cézanne, and fill the canvas with a colorful surface and a more painterly treatment than the hard-edge style of most of his later works. In Nord-Sud, the literary newspaper of that name appears in the still life, a compositional device common in cubist compositions, but also a reference to the literary and avant-garde interests of the painter.[48]

Magical realism

Starting in 1920, Miró developed a very precise style, picking out every element in isolation and detail and arranging them in deliberate composition. These works, including House with Palm Tree (1918), Nude with a Mirror (1919), Horse, Pipe and Red Flower (1920), and The Table – Still Life with Rabbit (1920), show the clear influence of Cubism, although in a restrained way, being applied to only a portion of the subject. For example, The Farmer's Wife (1922–23), is realistic, but some sections are stylized or deformed, such as the treatment of the woman's feet, which are enlarged and flattened.[49]

The culmination of this style was The Farm (1921–22). The rural Catalan scene it depicts is augmented by an avant-garde French newspaper in the center, showing Miró sees this work transformed by the Modernist theories he had been exposed to in Paris. The concentration on each element as equally important was a key step towards generating a pictorial sign for each element. The background is rendered in flat or patterned in simple areas, highlighting the separation of figure and ground, which would become important in his mature style.

Miró made many attempts to promote this work, but his surrealist colleagues found it too realistic and apparently conventional, and so he soon turned to a more explicitly surrealist approach.[50]

Early surrealism

In 1922, Miró explored abstracted, strongly coloured surrealism in at least one painting.[51] From the summer of 1923 in Mont-roig, Miró began a key set of paintings where abstracted pictorial signs, rather than the realistic representations used in The Farm, are predominant. In The Tilled Field, Catalan Landscape (The Hunter) and Pastoral (1923–24), these flat shapes and lines (mostly black or strongly coloured) suggest the subjects, sometimes quite cryptically. For Catalan Landscape (The Hunter), Miró represents the hunter with a combination of signs: a triangle for the head, curved lines for the moustache, angular lines for the body. So encoded is this work that at a later time Miró provided a precise explanation of the signs used.[52]

Surrealist pictorial language

Through the mid-1920s Miró developed the pictorial sign language which would be central throughout the rest of his career. In Harlequin's Carnival (1924–25), there is a clear continuation of the line begun with The Tilled Field. But in subsequent works, such as The Happiness of Loving My Brunette (1925) and Painting (Fratellini) (1927), there are far fewer foreground figures, and those that remain are simplified.

Soon after Miró also began his Spanish Dancer series of works. These simple collages, were like a conceptual counterpoint to his paintings. In Spanish Dancer (1928) he combines a cork, a feather and a hatpin onto a blank sheet of paper.[50]

Livres d'Artiste

Miró created over 250 illustrated books.[53] These were known as "Livres d' Artiste." One such work was published in 1974, at the urging of the widow of the French poet Robert Desnos, titled Les pénalités de l'enfer ou les nouvelles Hébrides ("The Penalties of Hell or The New Hebrides"). It was a set of 25 lithographs, five in black, and the others in colors.

In 2006 the book was displayed in "Joan Miró, Illustrated Books" at the Vero Beach Museum of Art. One critic said it is "an especially powerful set, not only for the rich imagery but also for the story behind the book's creation. The lithographs are long, narrow verticals, and while they feature Miró's familiar shapes, there's an unusual emphasis on texture." The critic continued, "I was instantly attracted to these four prints, to an emotional lushness, that's in contrast with the cool surfaces of so much of Miró's work. Their poignancy is even greater, I think, when you read how they came to be. The artist met and became friends with Desnos, perhaps the most beloved and influential surrealist writer, in 1925, and before long, they made plans to collaborate on a livre d'artiste. Those plans were put on hold because of the Spanish Civil War and World War II. Desnos' bold criticism of the latter led to his imprisonment in Auschwitz, and he died at age 45 shortly after his release in 1945. Nearly three decades later, at the suggestion of Desnos' widow, Miró set out to illustrate the poet's manuscript. It was his first work in prose, which was written in Morocco in 1922 but remained unpublished until this posthumous collaboration."

.jpg.webp)

Styles and development

In Paris, under the influence of poets and writers, he developed his unique style: organic forms and flattened picture planes drawn with a sharp line. Generally thought of as a Surrealist because of his interest in automatism and the use of sexual symbols (for example, ovoids with wavy lines emanating from them), Miró's style was influenced in varying degrees by Surrealism and Dada,[18] yet he rejected membership in any artistic movement in the interwar European years. André Breton described him as "the most Surrealist of us all." Miró confessed to creating one of his most famous works, Harlequin's Carnival, under similar circumstances:

How did I think up my drawings and my ideas for painting? Well I'd come home to my Paris studio in Rue Blomet at night, I'd go to bed, and sometimes I hadn't any supper. I saw things, and I jotted them down in a notebook. I saw shapes on the ceiling...[54]

Miró's surrealist origins evolved out of "repression" much like all Spanish surrealist and magic realist work, especially because of his Catalan ethnicity, which was subject to special persecution by the Franco regime. Also, Joan Miró was well aware of Haitian Voodoo art and Cuban Santería religion through his travels before going into exile. This led to his signature style of art making.

Experimental style

Joan Miró was among the first artists to develop automatic drawing as a way to undo previous established techniques in painting, and thus, with André Masson, represented the beginning of Surrealism as an art movement. However, Miró chose not to become an official member of the Surrealists to be free to experiment with other artistic styles without compromising his position within the group. He pursued his own interests in the art world, ranging from automatic drawing and surrealism, to expressionism, Lyrical Abstraction, and Color Field painting. Four-dimensional painting was a theoretical type of painting Miró proposed in which painting would transcend its two-dimensionality and even the three-dimensionality of sculpture.[55]

Miró's oft-quoted interest in the assassination of painting is derived from a dislike of bourgeois art, which he believed was used as a way to promote propaganda and cultural identity among the wealthy. Specifically, Miró responded to Cubism in this way, which by the time of his quote had become an established art form in France. He is quoted as saying "I will break their guitar," referring to Picasso's paintings, with the intent to attack the popularity and appropriation of Picasso's art by politics.[56]

The spectacle of the sky overwhelms me. I'm overwhelmed when I see, in an immense sky, the crescent of the moon, or the sun. There, in my pictures, tiny forms in huge empty spaces. Empty spaces, empty horizons, empty plains – everything which is bare has always greatly impressed me. —Joan Miró, 1958, quoted in Twentieth-Century Artists on Art

In an interview with biographer Walter Erben, Miró expressed his dislike for art critics, saying, they "are more concerned with being philosophers than anything else. They form a preconceived opinion, then they look at the work of art. Painting merely serves as a cloak in which to wrap their emaciated philosophical systems."[57]

In the final decades of his life Miró accelerated his work in different media, producing hundreds of ceramics, including the Wall of the Moon and Wall of the Sun at the UNESCO building in Paris. He also made temporary window paintings (on glass) for an exhibit. In the last years of his life Miró wrote his most radical and least known ideas, exploring the possibilities of gas sculpture and four-dimensional painting.

Exhibitions

Throughout the 1960s, Miró was a featured artist in many salon shows assembled by the Maeght Foundation that also included works by Marc Chagall, Giacometti, Brach, Cesar, Ubac, and Tal-Coat.

The large retrospectives devoted to Miró in his old age in places like New York (1972), London (1972), Saint-Paul-de-Vence (1973) and Paris (1974) were a good indication of the international acclaim that had grown steadily over the previous half-century; further major retrospectives took place posthumously. Political changes in his native country led in 1978 to the first full exhibition of his painting and graphic work, at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. In 1993, the year of the hundredth anniversary of his birth, several exhibitions were held, among which the most prominent were those held in the Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, and the Galerie Lelong, Paris.[58] In 2011, another retrospective was mounted by the Tate Modern, London, and travelled to Fundació Joan Miró and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Joan Miró, Printmaking, Fundación Joan Miró (2013). And two exhibitions in 2014, Miró: From Earth to Sky at Albertina Museum, and Masterpieces from the Kunsthaus Zürich, National Art Center, Tokyo.

Exhibitions entitled Joan Miró: Instinct & Imagination and "Miró: The Experience of Seeing" were held at the Denver Art Museum from 22 March – 28 June 2015 and at the McNay Art Museum from 30 September 2015 – 10 January 2016 (respectively), showing works made by Miró between 1963 and 1981, on loan from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid.[59][60][61][62][63] In 2018, he was exhibited alongside, among others, Henri Matisse, Le Corbusier, Raymond Hains and Éric Sandillon at the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Riga, Latvia.[64][65][66][67] This exhibition, titled "Colour of Gobelins: Contemporary Gobelins from the 'Mobilier national' collection in France," took place during the sixth edition of the Riga Textile Art.[64][65][66][67]

In Spring 2019, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, launched Joan Miró: Birth of the World.[68] Running until July 2019, the exhibit showcases 60 pieces of work from the inception of Miró's career, and including the influence of the World Wars. The exhibit features 60-foot canvasses as well as smaller 8-foot paintings, and the influences range from cubism to abstraction.[69]

Legacy and influence

Miró has been a significant influence on late 20th-century art, in particular the American abstract expressionist artists that include: Motherwell, Calder, Gorky, Pollock, Matta and Rothko, while his lyrical abstractions[70] and color field paintings were precursors of that style by artists such as Helen Frankenthaler, Olitski and Louis and others.[71] His work has also influenced modern designers, including Paul Rand[72] and Lucienne Day,[73] and influenced recent painters such as Julian Hatton.[74]

One of Man Ray's 1930s photographs, Miró with Rope, depicts the painter with an arranged rope pinned to a wall, and was published in the single-issue surrealist work Minotaure.

In 2002, American percussionist/composer Bobby Previte released the album The 23 Constellations of Joan Miró on Tzadik Records. Inspired by Miró's Constellations series, Previte composed a series of short pieces (none longer than about 3 minutes) to parallel the small size of Miró's paintings. Privete's compositions for an ensemble of up to ten musicians was described by critics as "unconventionally light, ethereal, and dreamlike".[75]

Recognition

In 1954 he was given the Venice Biennale print making prize, in 1958 the Guggenheim International Award.[18][76]

In 1981, the Palma City Council (Majorca) established the Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró a Mallorca, housed in the four studios that Miró had donated for the purpose.[77]

In October 2018, the Grand Palais in Paris opened the largest retrospective devoted to the artist until this date. The exhibition included nearly 150 works and was curated by Jean Louis Prat.[78]

Art market

Today, Miró's paintings sell for between US$250,000 and US$26 million; US$17 million at a U.S. auction for the La Caresse des étoiles (1938) on 6 May 2008, at the time the highest amount paid for one of his works.[79] In 2012, Painting-Poem ("le corps de ma brune puisque je l'aime comme ma chatte habillée en vert salade comme de la grêle c'est pareil") (1925) was sold at Christie's London for $26.6 million.[80] Later that year at Sotheby's in London, Peinture (Etoile Bleue) (1927) brought nearly 23.6 million pounds with fees, more than twice what it had sold for at a Paris auction in 2007 and a record price for the artist at auction.[81][82] On 21 June 2017, the work Femme et Oiseaux (1940), one of his Constellations, sold at Sotheby's London for 24,571,250 GBP.[83]

Gallery

"Les Fusains": 22, rue Tourlaque, 18th arrondissement of Paris where Miró settled in 1927.

"Les Fusains": 22, rue Tourlaque, 18th arrondissement of Paris where Miró settled in 1927.

Interior views of Museo Reina Sofía

Interior views of Museo Reina Sofía.jpg.webp) Hakone open-air museum

Hakone open-air museum Grande Maternite

Grande Maternite Sculpture at Fundació Joan Miró

Sculpture at Fundació Joan Miró Terrace view

Terrace view.jpg.webp) Mural installation at the Gourmet Room at the Terrace Plaza Hotel

Mural installation at the Gourmet Room at the Terrace Plaza Hotel

References

- ↑ "Miró, Joan" (US) and "Miró, Joan". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Miró". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ↑ "Miró". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ↑ "Joan Miro | Biography, Paintings, Style, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ↑ M. Rowell, Joan Mirό: Selected Writings and Interviews (London: Thames & Hudson, 1987) pp. 114–116.

- 1 2 Victoria Combalia, "Miró's Strategies: Rebellious in Barcelona, Reticent in Paris", from Joan Miró: Snail Woman Flower Star, Prestel 2008

- ↑ Doreen Carvajal, In Majorca, Atoning for the Sins of 1691, The New York Times, 7 May 2011

- ↑ Sarah Wildman, Mallorca's Jews Get Their Due, The Forward, 13 April 2012

- ↑ Penrose, Roland (1964). Joan Miró. The Arts Council. p. 11.

- ↑ "Joan Miró". Totally History. 7 June 2011.

- 1 2 Joan Miró exhibition catalogue, 16 February – 3 March 1918, Galeries Dalmau

- ↑ "Joan Miró images in Barcelona – Europe – Travel". The Independent. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- 1 2 Joan Miró a la Viquipèdia, Estat de la qüestió el juny de 2016, biography, Works, Fundació Joan Miró, Premi Joan Miró, Text and image sources

- ↑ Rosa Maria Malet, Joan Miró, Edicions 62, Barcelona, 1992, p. 20, ISBN 84-297-3568-2

- ↑ Georges Raillard, Miró, Debate, Madrid, 1992, pp. 48–54, ISBN 84-7444-605-8

- ↑ Joan Miró, Galerie La Licorne, 29 April – 14 May, 1921, París (exhibition catalogue)

- ↑ Exposició d'Art francès d'Avantguarda, Galeries Dalmau, 26 October – 15 November 1920 (catalogue)

- 1 2 3 "Collection Online | Joan Miró – Guggenheim Museum". Guggenheimcollection.org. 25 December 1983. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Jacques Lassaigne, Miró: biographical and critical study. Tr. Stuart Gilbert. (Paris: Editions d'Art Albert Skira, 1963) pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest. The Farm. Homage to Joan Miró. Ed. G. di San Lazzaro. New York: Tudor Publishing Company, 1972. pp. 34.

- ↑ "Collection Online". Guggenheimcollection.org. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Adams, Tim (20 March 2011). "Joan Miró: A life in paintings". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ↑ "The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation". The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation.

- ↑ Cahiers d'art: bulletin mensuel d'actualité artistique / director Christian Zervos, Galerie la Licorne, catalogue, 1934, pp. 21–36, Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France

- ↑ Umland, Anne. "A Challenge to Painting: Miró and Collage in the 1920s." Joan Miró. Ed. Agnes De la Beaumelle. London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2004. pp. 61–69.

- ↑ Spector, Nancy. "The Tilled Field, 1923–1924". Guggenheim display caption. Retrieved on 30 May 2008.

- ↑ Archived 17 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Matisse, Father & Son, by John Russell, published by Harry N. Abrams, NYC. Copyright John Russell 1999, pp.387–389 ISBN 0-8109-4378-6

- ↑ Archived 19 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Robin Adele Greeley, Surrealism and the Spanish Civil War. (New Haven: Yale University press, 2006) pp. 14–22.

- ↑ Jacques Lassaigne, Miró: biographical and critical study. Tr. Stuart Gilbert. (Paris: Editions d'Art Albert Skira, 1963) pp. 5–8.

- ↑ Renee Riese Hubert, Miró and Breton. Yale French Studies, No. 31, Surrealism (1964). pp. 52–59.

- ↑ Archived 26 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Art Works Lost in WTC Attacks Valued at". Insurancejournal.com. 8 October 2001. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Art treasures lost in trade center rubble – World – NZ Herald News". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Art Object Page". Nga.gov. 10 October 1977. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró a Mallorca". Miro.palmademallorca.es. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Joan Miró (Spanish), 1893–1983: Featured artist works, exhibitions and biography from Walton Fine Arts". Artnet.com. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ Delgado, Monteserrat; Bogousslavsky, Julien (2018). "Joan Miró and Cyclic Depression". Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience. 43: 1–7. doi:10.1159/000490400. ISBN 978-3-318-06393-6. PMID 30336457.

- ↑ Depression and the spiritual in modern art : homage to Miró. Joseph J. Schildkraut, Aurora Otero. Chichester [England]. 1996. p. 116. ISBN 0-471-95403-9. OCLC 33897959.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Depression and the spiritual in modern art : homage to Miró. Joseph J. Schildkraut, Aurora Otero. Chichester [England]. 1996. pp. 110n1. ISBN 0-471-95403-9. OCLC 33897959.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Gibson, M (1980). "Miró: When I see a tree ... I can feel that tree talking to me". ARTnews. 79: 52–56.

- ↑ Miró, Joan (August 1947). "In Francis Lee Interview with Miró". Possibilities. New York.

- ↑ Depression and the spiritual in modern art : homage to Miró. Joseph J. Schildkraut, Aurora Otero. Chichester [England]. 1996. pp. 117–8. ISBN 0-471-95403-9. OCLC 33897959.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Depression and the spiritual in modern art : homage to Miró. Joseph J. Schildkraut, Aurora Otero. Chichester [England]. 1996. p. 6. ISBN 0-471-95403-9. OCLC 33897959.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Depression and the spiritual in modern art : homage to Miró. Joseph J. Schildkraut, Aurora Otero. Chichester [England]. 1996. p. 7. ISBN 0-471-95403-9. OCLC 33897959.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Delgado, Montserrat G.; Bogousslavsky, Julien (2018). "Joan Miró and Cyclic Depression". Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists – Part 4. Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience. 43: 5–6. doi:10.1159/000490400. ISBN 978-3-318-06393-6. PMID 30336457.

- ↑ Stephan von Wiese Painting as Universal Poetry – the connection of painting and word in Miró. In Joan Miró – Snail Woman Flower Star Prestel, 2006

- ↑ Christa Lichtenstein From the Playful to a Denunciation of Violence: Miró's deformations of the 1920s and 1930s. In Joan Miró – Snail Woman Flower Star Prestel, 2006

- 1 2 Victoria Combalia, Miró's Strategies – Rebellious in Barcelona, Reticent in Paris In Joan Miró – Snail Woman Flower Star Prestel, 2006

- ↑ Estate of Raymond C. Hagel

- ↑ Stephan von Wiese Painting as Universal Poetry – the connection of painting and word in Miró., p. 58. In Joan Miró – Snail Woman Flower Star Prestel, 2008

- ↑ "Joan Miro – The Illustrated Books". Letubooks.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ Janis Mink, Miró (Los Angeles: Taschen, 2003), p. 43.

- ↑ "The Beginning of Painting and Drawing", Drawing and Painting: Children and Visual Representation, SAGE Publications Ltd, 2003, pp. 51–60, doi:10.4135/9781446216521.n4, ISBN 9780761947868

- ↑ Robert S. Lubar, Miro's defiance of painting, Joan Miró, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Centre Pompidou, Paris, Art in America, September 1994

- ↑ Walter Erben, Miró, André Sauret, Prestel Verlag, Monte-Carlo, Munich, 1960, re-edition 1980, Taschen, 1998, ISBN 3822873497

- ↑ "The Collection | Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893–1983)". MoMA. 16 May 1924. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Joan Miró: Instinct & Imagination Denver Art Museum, 22 March 2015. Archived 10 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Joan Miró: Instinct & Imagination Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Westword, 22 March 2015.

- ↑ Women, Birds and Stars Shine in Joan Miró: Instinct & Imagination at the DAM, Westword, 6 May 2015.

- ↑ Following Miró to the brilliant, and colorful, end in Denver Archived 3 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Denver Post, 27 March 2015.

- ↑ Bennett, Steve (2 October 2015). "McNay exhibits a glimpse into soul of Spanish master". San Antonio Express News. Expressnews.com. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- 1 2 "Colour of Gobelins. Contemporary Gobelins from the "Mobilier national" collection in France - Art Museums". www.lnmm.lv. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- 1 2 ""Gobelēnu krāsas"". laikraksts.com (in Latvian). Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- 1 2 Artdaily. "Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Riga looks into the textile collection of Mobilier national". artdaily.cc. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- 1 2 target="_blank">www.baltic-course.com</a>, <a href="http://www baltic-course com" (1 June 2024). "В Риге проходит выставка французских гобеленов - Культура, искусство - Latvijas reitingi". reitingi.lv (in Russian). Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ↑ "Joan Miró: Birth of the World". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ↑ Smith, Roberta (14 March 2019). "Miró's Greatness? It Was There From the Start". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ↑ New York Media, LLC (11 September 1972). NY Magazine, Sept. 11, 1972, Vol. 5, No. 37. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ "Artist Profile of Joan Miro". Nancy Doyle Fine Art. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ↑ "Joan Miró's Influence on Graphic Design". Museum of Modern Art (Audio lecture). Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ↑ Hemingway, Wayne. "Miro at the Tate". Facebook. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ↑ Silverstein, Joel (1 April 2001). "Curious Terrain". Reviewny.com. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

The paintings sing to each other ...

- ↑ "The 23 Constellations of Joan Miró – Bobby Previte | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic" – via www.allmusic.com.

- ↑ "Biography from ArtNet lists Miro's Gold Medal award from King Juan Carlos". Artnet.com. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ Archived 11 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Miró". www.grandpalais.fr.

- ↑ "As reported on APF Google, Miró painting fetches record price of US$17million at Christie's New York auction on May 6, 2008". Agence France-Presse. 6 May 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ "Joan Miro (1893–1983) | Painting-Poem ("le corps de ma brune puisque je l'aime comme ma chatte habillée en vert salade comme de la grêle c'est pareil") | Impressionist & Modern Art Auction | Christie's". Christies.com. 7 February 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Carol Vogel, Miró Painting Sets Record on Otherwise Lackluster Opening Night of London Auctions, New York Times Blog, 19 June 2012

- ↑ "Joan Miro painting smashes auction record". BBC. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Joan Miro, Femme et Oiseaux 1940, Sotheby's London".

Further reading

- Jacques Dupin, Joan Miró Life and Work, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., publisher, New York City, 1962, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 62-19132

- Margit Rowell, Joan Miró: Selected Writing & Interviews, Da Capo Press Inc; New edition (1 August 1992) ISBN 978-0-306-80485-4

- Joan Miró and Robert Lubar (preface), Joan Miró: I Work Like a Gardener, Princeton Architectural Press, Hudson, NY, 2017. Reprint of 1964 limited edition. ISBN 978-1-616-89628-7

- Josep Massot Joan Miró. El niño que hablaba con los árboles Galaxia Gutenberg, Barcelona, Spain, 2018. ISBN 9788417355012

- Orozco, Miguel (2016). La odisea de Miró y sus Constelaciones. Madrid: Visor. p. 397. ISBN 978-84-989-5675-7.

- Orozco, Miguel (2018). The true story of Joan Miró and his Constellations. Academia.edu.

External links

- Joan Miró works at the National Gallery of Art

- Joan Miró at the Museum of Modern Art

- Olga's Gallery: Joan Miró

- Artcyclopedia Directory of online works

- Joan Miró in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- Algorithmic emulation of the most basic aspects of the works of Joan Miró using random numbers and Bézier functions