| Johannisberg | |

|---|---|

| |

Johannisberg | |

| 50°54′5″N 11°37′4″E / 50.90139°N 11.61778°E | |

| Location | Thuringia |

| Country | Germany |

| Specifications | |

| Height | 373 meters above sea level[1] |

Johannisberg is a prominent ridge of the Wöllmisse, a Muschelkalk plateau east of Jena. The steeply sloping spur of land to the Saale Valley north of the district of Alt-Lobeda bears the remains of two important fortifications from the late Bronze Age and the early Middle Ages. Due to several archaeological excavations and finds recovered since the 1870s, they are among the few investigated fortifications from these periods in Thuringia. Of particular interest in archaeological and historical research is the early medieval castle. Due to its location directly on the eastern bank of the Saale, its dating and interpretation were and are strongly linked to considerations of the political-military eastern border of the Frankish empire. It is disputed whether it was a fortification of independent Slavic rulers or whether it was built under Frankish rule. According to a recent study, it may have been built in the second half of the 9th century in connection with the establishment of the limes sorabicus under Frankish influence.[2]

Topographical and geomorphological situation

The Johannisberg is located north of Jena-Lobeda on the eastern bank of the Saale. Together with the Kernberg to the north and the Jena Hausberg, it forms the southeast front of the middle Saale near Jena. Its steep slopes are formed by the over 100 m thick lower Muschelkalk, popularly also called Wellenkalk, from which several solid limestone banks emerge (see also Geology of the Middle Saale Valley).

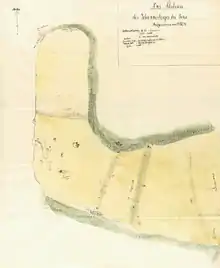

The Muschelkalk plateau of the Wöllmisse jumps out here with a boot-shaped spur far to the west. The Johannisberg with a height of 360–373 meters above sea level is limited in the north by the narrow Pennickental and in the south by the wide valley of the Roda. In the west it breaks off steeply, in the upper part almost vertically to the Saale Valley. The height difference is 215–220 m. It can be distinguished between a roughly trapezoidal plateau with 180 m of greatest length and 70 m of greatest width and the steeply sloping, ridge-shaped, northwest-facing peak with a length of about 200 m. To the east, the mountain, with an average width of 120 m, merges into the plateau of the Wöllmisse without any natural obstacle. There are two powerful springs in a small, deep water crack on the southern edge of the mountain, about 250 m south and 100 m below the plateau. North of the Johannisberg, the Pennickenbach flows in the valley about 140 m below.[3]

Description of the remains of the hillfort

Two main hillforts

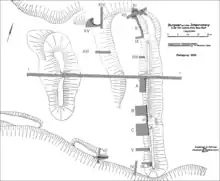

Due to the steep drop to the south, west and north, the plateau of Johannisberg is naturally protected. It therefore lent itself to the construction of a fortified hilltop settlement in prehistory and the early Middle Ages. At the narrowest part of the spur, access was sealed off with constructions made of wood, stones and earth. Due to their decay, today they appear only as hillforts. Theses ones are clearly preserved in the terrain, differing in size and shape. The western hillfort is about 48 m long, 1.60 m high and a little curved inwards. It runs along the narrowest part of the plateau from its northern to its southern edge. At a distance of 28 m to the east is a second straight hillfort, about 80 m long, 1.30 m high.[3]

Remains of the edge fortification

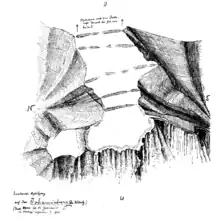

On the southern edge of the plateau, from the southern end of the western hillfort to the edge in the west, an approximately 35 m long, much lower hillfort has survived. A sketch from 1884 and a drawing from 1912 also show a hillfort at the transition from the trapezoidal plateau to the spur, where today only a clear terrain edge can be seen.[4] According to the older plan, the plateau was even surrounded by hillforts on all sides. Probably the low hillfort is the remainder of an edge fortification, which was preserved on the somewhat less rugged steep slope to the south here.

Presumed rampages

The existence of two further hillforts in the east adjoining apron is unclear. These are described in the older local history literature of the 1920s and 1930s[5] and are also recorded on the two drawings. While they are not mentioned in various publications by the excavator Gotthard Neumann in 1959 and 1960, Reinhard Spehr in 1994 spoke of a "straight line(s) of the two forewalls that had been overlooked so far."[6] The entire area today has been heavily reshaped by extensive reforestation since the 1950s. Further encroachments were probably made by entrenchment works in connection with the foot drill and Manöverplatz of the Jena garrison, which was used until the First World War. Without archaeological investigations it cannot be decided whether the relatively flat and rather irregular ground undulations and incisions to the east of the two hillforts mentioned are natural, geological phenomena or actually artificially created or at least expanded fortifications.[7] In the latter case, the site would be considerably enlarged once again.

Archaeological investigations on the Johannisberg

_Gel%C3%A4ndemodell.jpg.webp)

Excavations and finds recovery in the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.

The clearly pronounced hillfort complex attracted interest early on. The first excavations and recoveries of read finds were carried out by the founder of prehistoric and early historical research in Jena, Friedrich Klopfleisch, in the 1870s and 80s. These excavations, which usually lasted only one day and were mostly carried out with students in the context of Sunday "Archäolog. Exkursionen in die Umgegend Jena's", some records and sketches exist in Klopfleisch's diaries. Finds were recovered in several places and at least one cut through a hillfort was made. However, the exact location of the excavation sites is not known. Further recoveries of read finds and unsystematic excavations were carried out in the first half of the 20th century by archaeological amateurs. For example, Walther Cartellieri, a son of the Jena professor of history Alexander Cartellieri, carried out investigations west of the western hillfort around 1912, as shown by a sketch he made of the Johannisberg with an entry of the site. In the 1930s, employees of the Germanic Museum of the University of Jena, including Gotthard Neumann in particular, were able to recover further reading finds and thus expand the museum's holdings.

Excavations under Gotthard Neumann 1957 and 1959

The excavations by Gotthard Neumann in 1957 and 1959 brought about a significant progress in knowledge. Within three weeks in 1957, a 76 m long and about 1 m wide cut I was made through both hillforts. Neumann recognized the eastern hillfort, over 80 m long, with the remains of two stone blind walls, as being of early medieval origin, while the western hillfort dates from the late Bronze Age. After the excavations were completed, the brothers A. and G. Daniel unsystematically recovered some more finds in the cut between the two hillforts. During the four-week excavation campaign in 1959, several small areas and cuts were uncovered at the foot of the hillfort and at the presumed entrance to the north. The investigated areas reached a total size of about 270 m2, of which 167 m2 were in only 1 m wide sections. In the excavation areas, apart from the fortification, hardly any clear features and no stratigraphy were recognizable. This is on the one hand due to the low thickness of the humus cover, on the other hand certainly also due to the excavation methodology of the narrow sections, in which large-scale structures are usually very difficult to recognize.

The excavation in 1980 by the Museum of Prehistory and Early History

In August 1980, the Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Weimar conducted a one-week post-excavation under the direction of Sigrid Dušek. During this excavation, the area at the gate, which had already been investigated by Neumann, was uncovered again and extended, and another 4.90 × 2.10 meter area on the inner facing wall of the outer hillfort was investigated. The results remained unpublished and were only mentioned summarily in a few places in the literature.

Further investigations and finds recovery

In 1983 and 2002, further finds were deposited in the Museum Weimar, which could be picked up during the cultivation of the inner surface for the subsequent afforestation or recovered during a renovation of the inner blind wall. In spring and summer 2003, Tim Schüler of the Thuringian State Office for the Preservation of Monuments and Archaeology undertook geophysical measurements. An area of several square meters at the southern end of the plateau between the two hillforts was investigated using geomagnetics, and the absence of areal features was confirmed. In addition, a geoelectrical profile, also called a pseudo-profile, was made through the early medieval hillfort in the area of the current path, and two other pseudo-profiles were made through the remains of the edge hillfort in the southwest corner of the plateau.

In October 2003, the Department of Prehistory and Early History of the University of Jena was able to conduct a five-day follow-up investigation of the section through the early medieval hillfort made in 1959, in which the southern profile was moved back about half a meter and recorded again. This mostly confirmed Neumann's observations, but also modified them in some details.[8]

Late Bronze Age settlement phase

Research history

In the course of his excavations, Friedrich Klopfleisch was the first to recognize that Johannisberg had already been settled in prehistory and early history. He introduced the site to archaeological research in 1869. He dated the remains of the "einheimische(n) Töpferei", which in his view were made according to the "Vorbilde der römischen", initially to the "2.–4. Jahrhundert nach Chr."[9] In 1880, finds from Johannisberg were represented at the first large "Exhibition of Prehistoric and Anthropological Finds of Germany" in Berlin, initiated by Rudolf Virchow.

Johannisberg became increasingly known in archaeological research in 1909 at the latest, when it was included in the compilation of "vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Altertümer Thüringens" by Alfred Götze, Paul Höfer and Paul Zschiesche. From the "fortified with stone walls" Johannisberg a flint axe from the Neolithic, Bronze Age finds like "many animal bones, rubbing stones, charcoal and shards" and "some ornamented shards" are mentioned as "slavische Funde".[10] With the find inventory from the Johannisberg and other castle hillforts around Jena such as the Jenzig and the Alter Gleisberg near Bürgel, Götze recognized "an almost amazing correspondence with that of the older Lusatian castle hillforts."[11]

The prehistoric settlement on the Johannisberg was only studied again by Gotthard Neumann after the excavations in the late 1950s. In 1972, Klaus Simon presented a large part of the find material and a description of the prehistoric fortification in the course of his reappraisal of Hallstatt period sites in eastern Thuringia.

Finds and findings

A few late Neolithic finds probably only testify to a short-term use of the spur in this period. In the late Bronze Age and early Hallstatt period (HaB2 to HaC1) the spur was sealed off from the plateau for the first time with a sectional hillfort. The fortification, the remainder of which was preserved in the western hillfort, consisted of a wooden-reinforced fill of stream limestone, which was quarried on the uppermost valley level of the Pennickental, about 80 m below the plateau. Simon calculated that about 150 m³ of wall backfill had to be brought to the plateau by the builders. In front of this wood-earth-stone construction was a stone facing wall made of foamed lime blocks or slabs in dry construction, which probably originated mainly from a shallow material extraction trench directly in front of the wall. The back front was probably not designed as a ramp, as Neumann assumed, but apparently consisted of a wooden (plank) wall that later tilted inward.[12]

According to Simon, the mountain was temporarily abandoned during the Middle Hallstatt period (HaC2), similar to the Hasenburg near Haynrode and the Jenzig near Jena. As a reason for this he assumed, among other things, climatic changes in the Thuringian region, which made the Johannisberg temporarily unattractive as a settlement site. At the latest with the beginning of the late Hallstatt period (HaD1) the Johannisberg was visited again. The older fortification seems to have been used again, at least during the excavations there were no signs of an elaborate renewal of the old fortification or of the construction of a new one. Simon placed the end of the occupation in the La Tène A period, although it must be pointed out that a renewed inspection of the ceramic material did not reveal any pottery clearly still belonging to the La Tène period. Like the Dohlenstein near Kahla, the Felsenberg near Pössneck or the Weinberg near Oberpreillipp, the Johannisberg near Jena-Lobeda gradually lost its function in the late Hallstatt period and was abandoned as a settlement site. Only from the Alter Gleisberg near Bürgel there are several finds from the Latène period, among them also some fibulae.

Early medieval castle

A Slavic or Frankish site? Basic question of the previous research

In 1909 Alfred Götze evaluated the fragments of Slavic pottery already recovered by Klopfleisch merely as isolated finds and considered the fortification remains on the Johannisberg not as early medieval, but generally as prehistoric, in the special case as Bronze Age: "A part of our castle hillforts is Bronze Age, especially those which are called fire or slag hillforts, because they show a strong influence of fire".[13] In connection with Slavic settlement, on the other hand, he opined, "Whether purely Slavic castle hillforts, i.e. those erected by them as so often in eastern Germany, occur in Thuringia is doubtful; in any case, however, they sometimes took older castle hillforts into use."[14] This view of Götz remained decisive in the first half of the 20th century. It was followed by experts such as Klopfleisch's successor Gustav Eichhorn, Kurt Schumacher, Walter Schultz and almost literally Alfred Auerbach as well as by local historians from the middle Saale Valley. The dating of the site to the Bronze Age is certainly also the main reason why the castle on the Johannisberg did not play a role in the mostly bitter debates at the end of the 19th and in the first half of the 20th century about the relations between Franks/Germans and Slavs on the Saale. According to the generally accepted view of the time, "strong castles" of the early Middle Ages had only been built on the left bank of the Saale, and only "when the reconquest of the right bank of the Saale began in the 10th century, the right bank was also fortified with castles."[15] The first castles were built on the right bank of the Saale.

Gotthard Neumann, who shortly before had carried out one of the first modern investigations of an early medieval castle complex in Central Germany on the Slavic castle hillfort "Alte Schanze" in Köllmichen, today a district of Mutzschen, recognized Johannisberg as an early medieval ("Slavic") complex in 1931,[16] but initially did not elaborate on this dating. It will not least be due to the circumstances of the time that Neumann's address of Johannisberg as a Slavic castle wall could not at first gain acceptance, not even among archaeologists and historians with whom he was in close contact such as Werner Radig or Herbert Koch. It was not until the excavations in 1957 and 1959 that clear evidence was found that a fortification had been rebuilt on the site, which had already been used and fortified in the Bronze Age, at a slightly different location in the early Middle Ages.

Since then, research has almost always focused on the question of whether the early medieval castle on Johannisberg was a fortification of politically independent Slavic rulers or whether it had been built under France. The excavator Neumann regarded Johannisberg as a Sorbian fortification for the protection of the Saale border solely on the basis of historical considerations and thought that it might have existed between 751 and 937.[17] For Joachim Herrmann, in 1967, "given its location directly on the Saale [...] it was not readily certain to whom this castle served, whether the Sorbian inhabitants or the Carolingian empire." According to him, the fortification wall was built "at the latest in the 9th century". In the same context he counted the Johannisberg among "the undoubtedly under Frankish or ancient influence standing facilities in the Sorbian area."[18] In 1970 the Johannisberg was mentioned as an Old Slavic folk or refuge castle in the handbook "Die Slawen in Deutschland". According to the Marxist view of history, "the oldest castles [...] were built by peasant producers for their protection."[19] Sigrid Dušek wrote following her investigations in 1983: "The ethnic attribution of this castle is still disputed. Ceramics and fortification techniques [...] point to a Slavic foundation [...], on the other hand, the possibility of a Carolingian fortification is also considered."[20] In 1985, the site was described by her as "the westernmost and only probably Slavic castle hillfort investigated in the Thuringian Saale region."[21] Dušek also attributed Johannisberg to the Slavs in 1992 and most recently in 1999.[22] In 2006, Tim Schüler opined, "The finds speak for a Slavic fortification that served to secure the middle Saale Valley here in the 9th/10th century."[23]

Paul Grimm and Hansjürgen Brachmann, on the other hand, saw this as a Frankish foundation.[24] Reinhard Spehr, in 1994 and 1997, has spoken out most clearly in favor of the assumption of a late Frankish foundation with far-reaching conclusions. According to him, "the Franks built a castle with stone wall facades to secure the imperial border in the 8th century."[25] Against the "view presented again and quite apodictically by Spehr" Matthias Rupp again turned in 1995. Although he spoke of a "fortification on the Johannisberg which so far does not allow an unambiguous ethnic classification", he gave arguments against a Carolingian border castle with the parallels in Slavic castle construction, Slavic pottery and the strategic orientation of the fortification on the high plateau of the eastern bank of the Saale.[26] In 2002, Peter Sachenbacher counted Johannisberg among the "castles which, at the time of their construction, are to be addressed as purely Slavic in terms of their ethnos."[27] Four years later, he stated, "Today, it is correctly assumed that the predominance of Slavic pottery does not automatically suggest a Slavic castle, and that it is quite more likely that the complex was built under Carolingian rule."[28]

However, all these interpretations are based on general considerations about the political situation in the early and beginning high Middle Ages in the Elbe-Saale region rather than on the archaeological finds and features, since their significance in this respect is rather low.

The find material and its significance

The early medieval find material from Johannisberg is primarily Slavic pottery from the Leipzig district, including five complete and 19 vessels preserved or reconstructable in the upper part, and only a few pieces of metal, stone or bone. There are several knives with handle tangs and straight or slightly curved backs, which appear especially in the surrounding cemeteries of the 8th and 11th century, but also in numerous castles of this and more recent period. This is equally true for a knifepoint, an iron arrowhead with a flat, pointed oval blade, an undecorated knife sheath fitting, and two curved strips of sheet metal that can be regarded as ribbon-shaped finger rings. The majority of the finds are unstratified.

The find material can be dated predominantly to the 9th and 10th centuries. Whether and to what extent some of the pottery finds date back to the 8th century must be left open at the present state of research. A high Middle Ages ribbon-shaped handle probably indicates, as do a few other late medieval and modern pottery finds, only a sporadic use of the area in recent times.

Regarding the question of the political affiliation of the castle complex, the pottery finds do not allow any concrete statements. The dominance of Slavic pottery says nothing about the political affiliation of the castle lords. For example, during the excavations on the Burgberg in Meissen, a foundation of King Henry I after 929, almost exclusively Slavic pottery was also found in the find material. It merely reflects the conditions in the Slavic-populated surrounding countryside, from which the castle was supplied with food, including transport vessels and utensils.[29]

Construction and dating of the fortification

The early medieval fortification on the Johannisberg consisted of a mighty wood-earth construction sealing off the entire width of the spur, with dry-stone walls facing the outer and inner fronts, a moat in front, a surrounding perimeter fortification probably of the same construction, and possibly two additional hillforts in front. The new main fortification was built about 30 m east of the older hillfort, where the spur is much wider. Whether and to what extent the Bronze Age fortification was used and extended again in the early Middle Ages cannot be said.

A method of fortification with stone facing walls was long considered a genuinely Slavic characteristic.[30] However, more recent research shows that the ideas of an ethnic attribution of castle building techniques are not tenable.[31] Overall, there is a clear concentration of this building technique on the eastern fringes of the later Frankish empire.[32] Presumably, the method of fortification was adopted by the Western Slavs from the Franks, where the Roman-Late Antique building tradition had been preserved.[33] The Slavs were the first to adopt this method of fortification.

Furthermore, it is striking that many comparable fortifications in Central Germany are, according to current research, younger than assumed for a long time, e.g. the (later) Burgward center in Dresden-Briesnitz, the Burgwall "Bei den Spitzhäusern" and the Burgberg in Zehren or the castle on the Landeskrone near Görlitz. They were mainly built around the middle or in the second half of the 10th century and thus certainly under East Frankish-German rule. A direct connection with the establishment of the Ottonian castle guard system is obvious. The somewhat older complexes in the other Slavic areas, especially in Great Moravia, are also attributed in recent treatments to the influence of the East Frankish-Carolingian empire or mutual contacts between Franks and Slavs.[34]

Results of archaeological and historical research

The castle complex on the Johannisberg can so far only be roughly dated to the 9th and 10th century.[35] A settlement beginning already in the late 8th century is also possible. Since no reconstructions or renewals could be recognized in the fortification, an existence time of about 30 to 50 years can be assumed. The mass of ceramic finds and the bloom of the fortification type fall into the second half of the 9th and the first half of the 10th century, so that the fortification probably existed only in this period. The significance of the few findings is limited.

The quality and extent of occupation within the fortification remain unclear. The elaborate timber-earth construction with front and rear facing walls testifies to a longer-term use rather than a refuge fortified for a short time. The traces of building immediately behind the main wall and the peripheral fortifications as well as the central location of the Johannisberg are also indications of a permanent settlement. At the same time, the comparatively small number of finds, the lack of two-dimensional features and especially the absence of nearby water points speak against a permanent settlement with a larger scale and a larger number of occupants. The existence of so-called people's castles and castles of refuge in the sense of fortifications built by a community for its protection and only used in case of need has been increasingly questioned in recent years. Johannisberg is one of the large castles of the Carolingian period, which occur in the entire West Slavic settlement area and show numerous similarities in size, ground plan, wall construction and interior design. Their beginnings are in the 8th century, depending on the further historical development they are abandoned already in the 9th century or continue until the 10th/11th century. Based on the analogies in the Frankish sphere of power, but also on the few written sources for the West Slavic area, it becomes clear that developed dominions were behind the construction of these fortifications. Of course, this does not exclude the possibility that such castles were permanently inhabited by a larger number of people or were at least suitable for accommodating larger crowds in case of danger - certainly not exactly rare in view of constant disputes between the elites. In general, early and high medieval castles were not located at borders, but in the middle of the settled country. They fulfilled central functions within settlement chambers, i.e. they served here to control and protect the surrounding settlements and probably also to demonstrate and represent rule. The task of border surveillance and protection, as Neumann assumed, is atypical. On the basis of the finds and features from Johannisberg alone, it is not possible to decide on the political affiliation of the castle.

Therefore, the question must be asked whether the political-military border between the Frankish empire and the Slavs, the so-called limes sorabicus, ran along the middle and lower Saale at all. According to archaeological, historical and onomastic evidence, it can be assumed that the middle Saale Valley with the tributary valleys of the Orla, Roda and Gleise already formed a unified settlement and economic area in the early Middle Ages, the backbone of which was the river itself.[36] This assumption, of course, again directly touches the question of the interpretation of the castle on the Johannisberg. A sharp border along the middle Saale with a Slavic castle occupation largely independent of the Frankish empire is difficult to imagine. The fortification on Johannisberg will probably have been built in the second half of the 9th century in connection with the establishment of the limes sorabicus under Frankish influence. This, however, says nothing about the ethnicity of its inhabitants and certainly not of its builders. These were undoubtedly recruited from the Slavic populated surrounding countryside, as is also handed down for the construction of the Frankish castellum near Halle in 806. The castle crew was also supplied with food and commodities from the surrounding settlements, which explains the almost exclusive occurrence of Slavic pottery vessels.

Current use

Until after the World War II, the Johannisberg plateau was used as a grazing area for sheep. After the abandonment of pasture use, the area became overgrown with bushes. In the 1980s, it was reforested according to plan and, except for small areas in the west, is covered with a dense mixed forest.

Like the other mountains around Jena, Johannisberg is a popular hiking destination. Several well-maintained trails lead up the mountain from the northwest and south and further east to the plateau of the Wöllmisse. The 11.4 km long route "Johannisberg-Horizontale" is part of the approximately 100 km long circular hiking trail "Horizontale" around Jena. A local history trail, redesigned in 1999, provides information about natural features, geology and the flora and fauna of the eastern slope of the middle Saale valley. From the edge of the mountain in the west there is a wide view over the city and the middle Saale Valley.

A section of the Kernberglauf leads from the Fürstenbrunnen over the Johannisberg further to the Lobdeburg. Cycling and mountain biking are prohibited,[37] but the routes nevertheless exert a great attraction on cyclists.

References

- ↑ Radwander- und Wanderkarte Mittleres Saaletal ISBN 978-3-89591-098-2

- ↑ Grabolle 2007a; ders. 2007b; ders. 2008.

- 1 2 Grabolle, Johannisberg 2008, 11.

- ↑ Beide Zeichnungen in der Ortsakte Jena-Lobeda, Johannisberg, im Bereich für Ur- und Frühgeschichte der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena

- ↑ „Bald bemerken wir, daß der Weg durch eine Senkung eines querlaufenden Erdwalles führt. Zu diesem laufen im gleichen Abstande noch zwei Wälle mit der gleichen Senke. Auch dem ungeübten Auge fallen diese gleichmäßigen, halbkreisförmigen Erdwälle auf, die einen Abschluß nach der Hochebene hin bilden“; John Grieshammer: Vorgeschichtliche Wallburgen auf Jenas Höhen. In: Der Pflüger. Monatsschrift für die Heimat 3, 1926, S. 20–25. – „Weiter vorgeschoben liegen die Überreste von noch zwei Wällen, wenn man sie als solche ansprechen darf“; Karl Kolesch: Vorgeschichtliche Wallanlagen in der Nähe Jenas. In: Altes und Neues aus der Heimat. Beilage zum Jenaer Volksblatt 1909–1920. Neudruck der 1. und 2. Folge, Jena 1939, p. 11.

- ↑ Spehr, Christianisierung 1994, S. 52 Anm. 34. Vgl. auch ders., Kirchberg 1997, pp. 37 Anm. 2

- ↑ Vgl. Matthias Rupp: Die vier mittelalterlichen Wehranlagen auf dem Hausberg bei Jena. Städtische Museen, Jena 1995, ISBN 3-930128-22-5, pp. 114 f. Anm. 145, der mit Verweis auf die Angaben von Spehr einschränkend bemerkt, dass die Vorwälle noch des sicheren archäologischen Nachweises entbehren.

- ↑ Ausführlich zu den genannten Ausgrabungen bei Grabolle, Johannisberg 2008, pp. 11–15.

- ↑ N.N., Dreissigste Generalversammlung. Naumburg am 2. und 3. Oktober. In: Zeitschrift für die gesammten Naturwissenschaften 34, 1869, pp. 345–361, hier p. 352.

- ↑ Alfred Götze, Paul Höfer und Paul Zschiesche (Hrsg.): Die vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Altertümer Thüringens. Würzburg 1909, pp. 317 f. unter Oberwöllnitz.

- ↑ Alfred Götze: Übersicht über die Vor- und Frühgeschichte Thüringens. In: Götze, Höfer u. Zschiesche, Altertümer 1909, pp. IX–XLI, hier p. XXX.

- ↑ Simon, Höhensiedlungen 1984, p. 49

- ↑ Götze 1909, XXVIII.

- ↑ Götze 1909, XLI.

- ↑ Ernst Kaiser: Landeskunde von Thüringen. Erfurt 1933. p. 107; vgl. auch ebd. pp. 245 f.

- ↑ Gotthard Neumann: Tätigkeitsbericht des Germanischen Museums der Universität Jena (Anstalt für Urgeschichte) über die Zeit vom l. XI. 1930 bis zum 31. III. 1932. In: Nachrichtenblatt für deutsche Vorzeit 8, 1932, pp. 208–212, hier p. 210

- ↑ Neumann 1959; 1960a; 1960b.

- ↑ Joachim Herrmann: Gemeinsamkeiten und Unterschiede im Burgenbau der slawischen Stämme westlich der Oder. In: Zeitschrift für Archäologie 1, 1967, ISSN 0044-233X, pp. 206–258, hier pp. 207, 232, 236.

- ↑ Joachim Herrmann (Hrsg.): Die Slawen in Deutschland. Geschichte und Kultur der slawischen Stämme westlich von Oder und Neiße vom 6. bis 12. Jahrhundert. Ein Handbuch. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1970, p. 151(Veröffentlichungen des Zentralinstituts für Alte Geschichte und Archäologie der Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR, Bd. 14).

- ↑ Dušek 1983, p. 43.

- ↑ Dušek 1985, p. 554.

- ↑ Sigrid Dušek: Die Slawen in Thüringen. In: Hessen und Thüringen. Von den Anfängen bis zur Reformation. Eine Ausstellung des Landes Hessen. Historische Kommission für Hessen u. a., Marburg 1992, ISBN 3-89258-018-9, pp. 79 f.; dies.: Slawen und Deutsche. „Unter einem Hut“. In: dies. (Hrsg.): Ur- und Frühgeschichte Thüringens. Ergebnisse archäologischer Forschung in Text und Bild. Theiss-Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1504-9, pp. 181–195, hier p. 186.

- ↑ ders.: Archäologische Denkmale aus Jena und Umgebung sowie dem Saale-Holzland-Kreis, West. In: Ostritz, Jena und Umgebung 2006, pp. 9–112, hier p. 64.

- ↑ Hansjürgen Brachmann: Die Wallburg „Der Kessel“ von Kretzschau-Groitzschen, Kr. Zeitz – Vorort eines sorbischen Burgbezirkes des 9. Jahrhunderts. In: Karl-Heinz Otto und Joachim Herrmann (Hrsg.): Siedlung, Burg und Stadt. Studien zu ihren Anfängen. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1969, pp. 343–360, hier p. 347 Anm. 6 (Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Schriften der Sektion für Vor- und Frühgeschichte Bd. 25); ders., Slawische Stämme an Elbe und Saale. Zu ihrer Geschichte und Kultur im 6. bis 10. Jahrhundert – auf Grund archäologischer Quellen. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1978, p. 238 Anm. 100 (Schriften zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte Bd. 32)

- ↑ Reinhard Spehr: Christianisierung und früheste Kirchenorganisation in der Mark Meißen. In: Judith Oexle (Hrsg.): Frühe Kirchen in Sachsen. Ergebnisse archäologischer und baugeschichtlicher Untersuchungen. Theiss-Verlag, Stuttgart 1994. ISBN 3-8062-1094-2, pp. 8–63, hier p. 15 Abb. 8 (Veröffentlichungen des Landesamtes für Archäologie mit Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte Bd. 23); vgl. auch p. 52 Anm. 34 und Spehr 1997.

- ↑ Matthias Rupp: Die vier mittelalterlichen Wehranlagen auf dem Hausberg bei Jena. Städtische Museen, Jena 1995, ISBN 3-930128-22-5, pp. 114 f. Anm. 145.

- ↑ Peter Sachenbacher: Neuere archäologische Forschungen zu Problemen der mittelalterlichen Landnahme und des Landesausbaus in Thüringen östlich der Saale. In: Rainer Aurig, Reinhardt Butz, Ingolf Gräßler u. André Thieme (Hrsg.): Im Dienste der historischen Landeskunde. Beiträge zu Archäologie, Mittelalterforschung, Namenkunde und Museumsarbeit vornehmlich aus Sachsen. Sax-Verlag, Beucha 2002, ISBN 3-934544-30-4 (Festschrift für Gerhard Billig), pp. 25–34, hier p. 32.

- ↑ Peter Sachenbacher: Zur Rolle der Burgen im Prozess des mittelalterlichen Landesausbaus in der Germania Slavica in Thüringen. In: Burgen in Thüringen. Geschichte, Archäologie und Burgenforschung. Schnell & Steiner, Rudolstadt/Saale und Regensburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-7954-2008-6 (Jahrbuch der Stiftung Thüringer Schlösser und Gärten. Forschungen und Berichte zu Schlössern, Gärten, Burgen und Klöstern in Thüringen Bd. 10, ISSN 1614-3809), pp. 13–21, hier pp. 13 f.

- ↑ Vgl. Grabolle, Johannisberg 2008, pp. 19–36.

- ↑ Joachim Herrmann: Gemeinsamkeiten und Unterschiede im Burgenbau der slawischen Stämme westlich der Oder. In: Zeitschrift für Archäologie 1, 1967, ISSN 0044-233X, pp. 206–258.

- ↑ Sebastian Brather: ‘Germanische’, ‘slawische’ und ‘deutsche’ Sachkultur des Mittelalters – Probleme ethnischer Interpretation. In: Ethnographisch-Archäologische Zeitschrift 37, 1996, pp. 177–216, hierzu pp. 186–193; ders.: Feldberger Keramik und frühe Slawen. Studien zur nordwestslawischen Keramik der Karolingerzeit. (Universitätsforschungen zur prähistorischen Archäologie Bd. 34. Schriften zur Archäologie der germanischen und slawischen Frühgeschichte Bd. 1). Habelt, Bonn 1996, ISBN 3-7749-2768-5, 187–196; ders.: Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. (Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde Bd. 30). de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-017061-2, pp. 132–140.

- ↑ Hansjürgen Brachmann: Zur Herkunft und Verbreitung von Trocken- und Mörtelmauerwerk im frühmittelalterlichen Befestigungsbau Mitteleuropas. In: Gerd Labuda und Stanisław Tabaczyński (Hrsg.): Studia nad etnogenezą Słowian i kulturą Europy wczesnośredniowiecznej. Festschrift für Witold Hensel. Bd. 1. Zakład Narod. Im. Ossoliń., Wrocław 1987, pp. 199–215; Joachim Henning: Ringwallburgen und Reiterkrieger. Zum Wandel der Militärstrategie im ostsächsisch-slawischen Raum an der Wende vom 9. zum 10. Jahrhundert. In: Guy de Boe und Frans Verhaeghe (Hrsg.): Military Studies in Medieval Europe (Papers of the „Medieval Europe Brugge 1997“ Conference. Instituut voor het Archeologisch Patrimonium rapporten Bd. 11.) IAP, Zellik 1997, ISBN 90-75230-12-5; S. 21–31, hierzu v. a. 24 f. Abb. 12; Rudolf Procházka: Zur Konstruktion der Wehrmauern der slawischen Burgwälle in Mähren im 8. bis 12./13. Jahrhundert. In: Joachim Henning und Alexander T. Ruttkay (Hrsg.): Frühmittelalterlicher Burgenbau in Mittel- und Osteuropa. Tagung Nitra vom 7. bis zum 10. Oktober 1996. Habelt, Bonn 1998, ISBN 3-7749-2796-0; pp. 363–370; Arne Schmid-Hecklau: Archäologische Studien zu den Kontakten zwischen dem Markengebiet und Böhmen im 10. und 11. Jahrhundert. In: Arbeits- und Forschungsberichte zur sächsischen Bodendenkmalpflege 45, 2003, ISSN 0402-7817, pp. 231–261, hierzu pp. 239–244.

- ↑ Brachmann 1987; ders.: Zum Burgenbau salischer Zeit zwischen Harz und Elbe. In: Horst Wolfgang Böhme (Hrsg.): Burgen der Salierzeit. T. 1. In den nördlichen Landschaften des Reiches. (Publikation zur Ausstellung „Die Salier und ihr Reich“. RGZM-Monographien Bd. 25.). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1992, ISBN 3-7995-4134-9, pp. 97–148, hierzu 122 Anm. 72.

- ↑ Vgl. hierzu zusammenfassend Grabolle, Johannisberg 2008, S. 37–41 mit den jeweiligen Einzelnachweisen.

- ↑ Grabolle, Johannisberg 2008, pp. 43f.

- ↑ Grabolle, Johannisberg 2008, pp. 53–64.

- ↑ Thüringer Staatsanzeiger Nr. 46/2004: § 3 Absatz 2 Nr. 2 Thüringer Verordnung über das Naturschutzgebiet „Kernberge und Wöllmisse bei Jena“. (PDF) Freistaat Thüringen, 12. Oktober 2004, p. 2528.

Bibliography

- On geology, flora and fauna:

- To the prehistoric and early historic fortifications:

- Sigrid Dušek: Geschichte und Kultur der Slawen in Thüringen. Erläuterungen zur Ausstellung. Museum für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Thüringens, Weimar 1983.

- Sigrid Dušek: Bedeutung Jenas und Umgebung für die slawische Archäologie. In: Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift. Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Gesellschaftswissenschaftliche Reihe 34, 1985. pp. 547–557.

- Roman Grabolle: Die frühmittelalterliche Burg auf dem Johannisberg bei Jena-Lobeda. In: Burgen und Schlösser. Zeitschrift für Burgenforschung und Denkmalpflege 48, 2007, ISSN 0007-6201, pp. 135–143.

- Roman Grabolle: „... ac salam fluvium, qui Thuringos et Sorabos dividit ...“. Das Gebiet der mittleren Saale als politisch-militärische Grenzzone im frühen Mittelalter. In: Arbeitskreis für Kulturlandschaftsforschung in Mitteleuropa ARKUM e.V. (Hrsg.): Siedlungsforschung: Archäologie, Geschichte, Geographie 25, 2007, ISSN 0175-0046.

- Roman Grabolle: Die frühmittelalterliche Burg auf dem Johannisberg bei Jena-Lobeda im Kontext der Besiedlung des mittleren Saaletals. Verlag Beier und Beran, Jena und Langenweißbach 2008. (Jenaer Schriften zu Vor- und Frühgeschichte Bd. 3), ISBN 978-3-941171-04-6

- Gotthard Neumann: Der Burgwall auf dem Johannisberge bei Jena-Lobeda. Kurzbericht über die Ausgrabung des Vorgeschichtlichen Museums der Universität Jena 1957. In: Ausgrabungen und Funde 4, 1959, ISSN 0004-8127, pp. 246–251 Taf. 40.

- Gotthard Neumann: Der Burgwall auf dem Johannisberge bei Jena-Lobeda. Kurzbericht über die Ausgrabung des Vorgeschichtlichen Museums der Universität Jena 1959. In: Ausgrabungen und Funde 5, 1960, ISSN 0004-8127, pp. 237–244.

- Gotthard Neumann: Zwei uralte Burgen auf dem Johannisberge bei Jena-Lobeda. In: Karl-Heinz Götze u. a.: Altes und Neues aus Jena. Ein Heimatalmanach aus dem mittleren Saaletal. Deutscher Kulturbund, Jena o. J. (1960), pp. 74–77.

- Sven Ostritz (Hrsg.): Jena und Umgebung. Saale-Holzland-Kreis, West (Archäologischer Wanderführer Thüringen Bd. 8). Verlag Beier und Beran, Langenweißbach 2006, ISBN 3-937517-50-2, S. 64 f.

- Klaus Simon: Die Hallstattzeit in Ostthüringen. Teil I: Quellen (Forschungen zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte Bd. 8). Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1972.

- Klaus Simon: Höhensiedlungen der Urnenfelder- und Hallstattzeit in Thüringen. In: Alt-Thüringen 20, 1984, ISSN 0065-6585, pp. 23–80.

- Reinhard Spehr: Zur spätfränkischen Burg „Kirchberg“ auf dem Johannisberg über Lobeda. In: Landesgruppe Thüringen der Deutschen Burgenvereinigung e.V. zur Erhaltung der historischen Wehr- und Wohnbauten (Hrsg.): Burgen und Schlösser in Thüringen. Jahresschrift der Landesgruppe Thüringen der Deutschen Burgenvereinigung 1997, pp. 21–38.