John Knight (1708–1774) was an English slave trader.[1] He was responsible for at least 114 slave voyages in the period 1750–1775 and he transported over 26,000 Africans to the Americas.[2] Knight traded enslaved Africans with the American politician and slave owner Henry Laurens.

Early life

Knight was born in Liverpool in 1708. His father, John Knight, was a physician.[1]

Slave trade

.jpg.webp)

Knight was responsible for at least 114 slave voyages in the period 1750–1775, he delivered over 26,000 Africans to the Americas.[2] He operated out of the Port of Liverpool and bought over 40% of his enslaved people from the Bight of Biafra off the West African coast, in the easternmost part of the Gulf of Guinea. In Nigeria, the Bight of Biafra has now been renamed the Bight of Bonny. The Bight of Biafra was commonly used by Liverpool slave traders.[3]

Knight was a member of the African Company of Merchants. Prior to 1750 the British Crown held a monopoly of rights for slave trading in West Africa with a business called the Royal African Company. Knight began slave trading in 1750, the year that the monopoly ended.[4]

Knight was the owner of the slave-ship Fanny.[5][6] Its Captain, William Jenkins, bought 171 Africans in May 1755. Knight gave Jenkins instructions to sell the enslaved people for £30, if he was unable to achieve this price in the West Indies, he was told to sail to America and sell them there. The surviving enslaved people were sold in Saint Kitts; 20 had died during the voyage.[6]

Letters from Henry Laurens

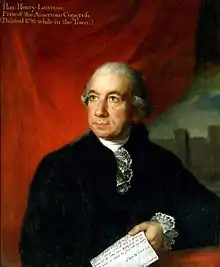

Knight regularly sold enslaved Africans to Henry Laurens, an American slave trader, slave owner, plantation owner, political leader during the American Revolutionary War and one of the largest slave traders in British North America. Laurens described Knight as his friend, and some of the correspondence between the two has been preserved and records their slave trading.[6]

A letter addressed to Knight from Laurens gives insight into the attitude of slave traders to their African captives. A ship called Emperor and captained by Charles Gwynn had embarked from Africa with 390 enslaved people on board; 120 of them had died. Laurens laments the loss of the £2,000 that these people could have been sold for. The ship was owned by Laurens and bound for his home town, Charleston, South Carolina.[5][6]

Laurens left the slave trade in 1762, but Knight tempted him to return to the trade the following year. Laurens wrote to Knight "he would rather not pursue that trade" but indicated he would sell the cargo for Knight. Laurens also wrote that the price of enslaved people was too low - because crops of rice and indigo were selling poorly, necessitating the use of less labour.[7]

Laurens wrote to Knight and other Liverpool slave traders in 1755. He was expressing his concern about the effect of shipworms on the slavers' ships. He wrote that the Enterprise owned by Knight was so rotten that it had been condemned. The shipworm responsible was the teredo. Laurens also wrote to Knight about a bill before the colonial assembly that would tax and effectively stop the slave trade for three years from 1766. Laurens voted against the bill but was overruled.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 Richardson 2007, p. 201.

- 1 2 Morgan, Kenneth. "Slave Trade Records from Liverpool, 1754–1792 – Description". British Online Archives.

- ↑ Richardson 2007, p. 28.

- ↑ Williams 1897, p. 674.

- 1 2 "Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade – Database". www.slavevoyages.org.

- 1 2 3 4 Dietz, Martin. "Conduct in the Transatlantic Slave Trade" (PDF). University of California at Santa Cruz.

- 1 2 Cox, Samuel. "Slavery and a Low Country South Carolina Merchant". W&M Scholar Works.

Sources

- Richardson, David (2007). Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-066-9.

- Williams, Gomer (1897). History of the Liverpool Privateers. UK: Liverpool University Press.