John L. Anderson | |

|---|---|

Captain John L. Anderson ca. 1928 | |

| Born | John Laurentius Anderson November 11, 1868 Gothenburg, Sweden |

| Died | May 18, 1941 (aged 72) |

| Resting place | Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Seattle |

| Occupation(s) | Ferry operator, ship builder |

| Spouse(s) | Emilie K. Anderson née Matson, married 1895 |

Captain John Laurentius Anderson was a preeminent figure in Washington state maritime industries in the first half of the twentieth century, particularly ferry service, shipbuilding, and ship-based tourism. He ran the largest ferry fleet on Lake Washington for three decades. He ran a large ferry fleet in Puget Sound. He built more than a dozen vessels at his shipyards, including the first ocean-going ship ever built on Lake Washington.

Early life

.jpeg.webp)

Anderson was born on November 11, 1868, in Gothenburg, Sweden.[1] He was the eldest of four children in a seafaring family. Both his father, Anders Jacobson, and an uncle were mariners. At the age of 14, in 1882, he joined his uncle on one of his cargo vessels sailing across the Atlantic. On his second trip he was taken ill and was left in Quebec to recover. He made his way to Schrieber, Ontario, where he found a job with the Canadian Pacific Railway, managing a crew of painters.[2]

Anderson arrived in Seattle at the age of 20 in 1888. He worked his way up in the maritime industry. He was a deckhand on George W. Elder, Olympian and Point Arena, on which he was promoted to fireman. He worked as fireman on the tug Rainier, owned by the Stetson and Post Lumber Company. He joined the crew of C.C. Calkins as a deckhand and rose to become captain after two years of service. His captain's pay was $100 per month.[3] The economic problems caused by the Panic of 1893 resulted in C.C. Calkins' owner taking her out of service. Captain Anderson lost his ship, but with the experience he gained and the money he saved, he was able to start his own steamboat business.

Steamboat operator (1892–1897)

During this early phase of Anderson's career, he owned a single ferry and ran it as captain, a simple and common business model of the day.

Winnifred was launched in 1892 from the shipyard of N. C. Peterson. Captain Anderson and James M. Colman owned the steamer as equal partners. She operated as a passenger ferry between Leschi Park in Seattle and Newcastle, on the east side of Lake Washington. The fare was 50 cents for a round trip. Winnifred burned at the dock at Leschi Park on September 12, 1894. Anderson blistered his feet trying to save her. While the ship was insured for $3,000, the partners had invested $4,500 in her.[4]

Anderson made arrangements to replace Winnifred with Quickstep the day after the fire. He was quoted as saying that while they may be "slightly disfigured, they are still in the ring" and intended to keep the Leschi Park–Newcastle service running.[4] Later that month, Anderson bought Quickstep and he recommenced the Newcastle service on September 27, 1894.[5] Anderson ran three roundtrips per day for passengers and freight. He was an early and life-long proponent of excursion trips on Lake Washington, so Quickstep also ran an evening cruise around Mercer Island every day except Sunday. Early on Sunday January 3, 1897, Quickstep caught fire while tied to her dock at Leschi Park. She was cut loose and floated out into Lake Washington so that the flames would not spread. She burned to the waterline and was a complete loss. She was insured for $1,500.[6]

Steamboat entrepreneur (1897–1904)

As Anderson's skills, experience, and industry connections grew, he branched out to become a marine project manager, ship broker, and deal maker, as well as a ship captain. His projects were opportunistic, taking advantage of various commercial situations as he found them. Anderson bought and sold ships quickly, and reported that, "every time I sold I made money."[3]

.jpg.webp)

In January 1897, Anderson let a contract to N. C. Peterson to build a replacement for Quickstep, which was christened Lady of the Lake. The new ship incorporated the engine from Quickstep, which was salvaged after the fire.[7] By June, 1897, Anderson was sailing his old route from Leschi Park to Newcastle to East Seattle on Mercer Island with his new ship.[8] By August 1897, however, he had sold his new ship to C. E. Curtis of Whatcom for $4,700, and bought Curtis' smaller ship, the steamer Effort, for $17.[9] Captain Anderson ran Effort between Olympia, Shelton, and Tacoma, in south Puget Sound in 1897.[2][10]

Anderson had the steamer Leschi built during the winter of 1897-1898. She was launched in March 1898.[11] One source reports that Anderson intended to use the vessel as a passenger ferry on Lake Washington. In any case, he sold the vessel to the U.S. Government for $2,500 almost immediately upon her completion.[3] Leschi became the steam launch Lillie, part of the Quartermaster's Department of the United States Army.[12][13]

After the sale of Leschi, Anderson had the steamer Acme built by Gustavus V. Johnson at his Lake Washington Shipyard.[14] She was completed in June 1899.[15] She provided ferry service from Leschi Park to Madison Park. Acme was the flagship of a Lake Washington flotilla in honor of the Washington State Press Association on July 12, 1899.[16] Anderson sold Acme in the fall of 1899, likely in October when press reports noted that he was replaced as master of the vessel.[17] At about the same, he came into possession of City of Renton which he sold to Harrie E. Tompkins for $1,000 on August 21, 1900.[18]

Anderson's next project was one of his most complex. The Inland Flyer was built in Portland for service on the Columbia River. Her sea trials began in September 1898 and mechanical problems arose immediately.[19] Federal steamboat inspectors required changes in her equipment soon after her launch.[20] Her machinery, built by the Marine Ironworks of Chicago, never gave satisfaction and was removed.[21] Her hull was moored, awaiting a solution to her mechanical problems, when Anderson came upon her during a visit to Portland in 1900. Anderson arranged for the Dalles, Portland & Astoria Navigation Company to sell the hull to the La Connor Trading and Transportation Company in December 1900.[22] He had the engine from Cyrene removed and then supervised its installation in Inland Flyer.[23][3] In February 1901, he sailed her from Portland to Seattle in only two days, perhaps a record for a vessel of her size.[24] Inland Flyer completed her fitting our in Seattle prior to beginning her service as a ferry in Puget Sound.

Anderson found a profitable niche purchasing large yachts. He purchased Elsinore from Seattle jeweler Albert Hansen. On March 28, 1903, he sold her for $3,000 to George A. Jenkins for use on Lake Whatcom.[13][25][26] In March 1900, Anderson bought the steam yacht Cyrene from Lawrence J. Colman, son of his partner in Winnifred, James M. Colman.[27] After installing her original engine in Inland Flyer, he had a new one built for Cyrene. Instead of selling her and moving on to the next project, Anderson sailed her from Puget Sound to Lake Washington and ran passenger ferry and excursion trips.[28] On February 21, 1903, Anderson took over James M. Colman's yacht Xanthus and moved her to Lake Washington as well.[29] By July 1903, Anderson was providing scheduled passenger ferry service with Cyrene and Xanthus running between Madison Park, Madrona Park, and Leschi Park every half hour.[30] After the busy 1903 summer season on the lake, Anderson had Cyrene lengthened from 75 feet (23 m) to 100 feet (30 m) at a cost of $4,000.[31]

In June 1904 the sternwheel steamboat Mercer was launched in Lake Washington.[32] Anderson had the ship built for the ferry run between Leschi Park, East Seattle on Mercer Island, and various points on Mercer Slough.[33] Mercer also ran daily excursion trips around Mercer Island from Leschi Park.[34] On October 30, 1905, Captain Anderson contracted for the construction of Fortuna. He was quoted at the time saying, "travel on Lake Washington has increased to such an extent that this new steamer has become a necessity. It has been my ambition to have a fast steamer for excursion purposes."[35]

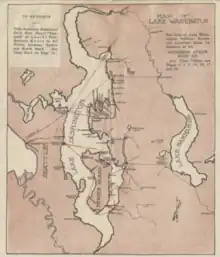

Lake Washington Operations

Anderson Steamboat Company (1905–1917)

Rather than buying and selling vessels, or overseeing their construction for others, as he had been doing since 1897, by 1902 Anderson was building his own fleet. In this phase of his career, he was managing a large and growing company of increasing complexity. In 1905 he began advertising as the Anderson Steamboat Company for the first time.

In late 1906 the Anderson Steamboat Company was incorporated in Washington State with a capital stock of $200,000. The directors included John L. Anderson, Captain Harrie E. Tompkins, and bankers Jacob Furth and J. F. Lane.[36] On November 27, 1906, Anderson announced a merger between Anderson Steamboat Company and B. & T. Transportation Company,[37] owned by Captains George Bartsch and Harrie E. Tompkins. The merger was executed on December 31, 1906. The combined company had a near-monopoly on ferry service on Lake Washington, including King County, which was owned by King County, but leased to Bartsch and Tompkins.[38] Anderson Steamboat Company contributed the steamers Cyrene, Xanthus, Fortuna, and Mercer, the launch Ramona, and the tug Hornet. In addition to the King County charter, B. & T. Transportation contributed steamers Gazelle, and Dorothy, the launch Avis, and the tug Success. Bartsch and Tompkins received stock in Anderson Steamboat Company in return for their ships. Anderson was president, and Tompkins was manager of the merged organization.[39][40]

The shipping business on Lake Washington boomed. There were so many customers that Anderson Steamboat Company was fined in 1907 for overloading both Cyrene and Xanthus.[41] Anderson ordered two new ships, Urania, and Atlanta, to meet the demand. In discussing the expansion of his fleet, Anderson said, "I believe business on Lake Washington will this year [1907] be double that of any previous year".[42]

In March 1907 King County was taken out of service. Federal marine inspectors found rot throughout her decks and planking.[43] As if to underline the seriousness of her deficiencies, she sank at her dock on May 20, 1907.[44] She had been running between Kirkland and Madison Park, one of the longer routes on Lake Washington. The loss of King County was an emergency for people and businesses in the Kirkland area. Public pressure caused the county commissioners to act. When King County was operated by Anderson Steamboat Company, the county provided a subsidy of $200 per month.[45] In March 1908, Captain Anderson secured a $300 per month subsidy from King County in return for running his own ships on the route until the county's new ferry, Washington, could be launched and put into service later that year.[46] Since the county had only one ship, whenever Washington was taken off her route for repairs, it came to Anderson to fill the gap. There was often wrangling over a fair rate of reimbursement for this temporary work.[47] Anderson's fleet had become so important to the area that he spent the rest of his career financially and politically involved, and often in conflict, with local governments.

.jpg.webp)

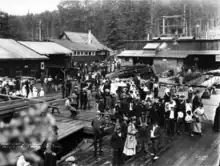

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was planned for the summer of 1909. Importantly for John Anderson, the "water gate" of the Exposition grounds was a pier on Union Bay in Lake Washington. Anderson secured exclusive access to this pier, the only one on the Exposition grounds. Two competitors, the Interlaken and Laurelhurst Steamship Companies, arranged to use a dock nearby.[48] Transporting tourists to the Exposition and lake excursions by visitors at the Exposition were business opportunities that exceeded the capacity of the Anderson Steamboat Company fleet. Captain Anderson built two more ships, Triton and Aquilo, both of which launched in May 1909, just in time for the Exposition's opening in June.[49] The crowds were huge, over 3 million visitors before the end of the event. Anderson's ships were packed. In fact, Aquilo was fined for exceeding her licensed passenger capacity on opening day.[50]

The Exposition closed on October 16, 1909, creating immediate excess capacity in the Lake Washington ferry fleet. Two days later Captain Anderson reassigned Atlanta to run in direct competition with the Interlaken Steamship Company passenger ferries. Since Atlanta was faster than the two Interlaken ships, she gained the bulk of the business. With its cashflow cut off, Interlaken could not pay its bills. Creditors seized Interlaken's two vessels, L. T. Haas, and Wildwood, which were sold to the Anderson Steamboat Company in November 1909. Captain Anderson eliminated his largest competitor quickly and without a costly rate war, maintaining his near-monopoly on Lake Washington ferry service.[51]

While Anderson's business boomed, four of his steamboats were lost. The first occurred on September 19, 1910, when Wildwood caught fire at her dock. Her upper works were gone when her mooring lines burned through and she began to drift towards several houseboats. By this time, Captain Anderson and a couple of boys had got steam up in Atlanta. He rushed to the scene and managed to tow Wildwood away from the houseboats, without also setting Atlanta on fire. Wildwood was burned almost to the waterline. While the ship was insured, Anderson opined on the day of the fire that it would likely be cheaper to build a new ship than to repair Wildwood.[52] This appears to be what happened, as Wildwood drops out of press accounts after the fire. Urania suffered a similar fate. On February 12, 1914, she caught fire at her dock in Houghton. Fortuna was able to extinguish the fire after an hour, but Urania's upper works and machinery were damaged.[53] She was insured but never rebuilt, as evidenced by her dropping out of Federal registry and subsequent press accounts. Captain Anderson built Dawn to replace her.[54]

L. T. Hass was one of the first steamers on Lake Washington. Federal marine inspectors found significant rot in the ship and condemned her. She was not worth repairing. Her engine and machinery was removed at Houghton. The hulk was towed out into Lake Washington, where it was set on fire on the night of July 28, 1913. The flaming ship caused some alarm, as many assumed that one of the regular steamers with passengers aboard was burning.[55][56]

The fourth ship lost by Anderson Steamboat Company was Triton. At about 4 p.m. on September 24, 1916, she hit a snag off the south end of Mercer Island. The snag punctured the hull but remained in place for several minutes acting as a plug. When the snag fell away, Triton began taking on water rapidly. Captain H. A. Riddle beached the vessel on the south shore of Mercer Island and safely landed the passengers and crew before Triton settled to the bottom on her starboard side. The accident occurred two months after the Lake Washington Ship Canal was opened and the lake level had been lowered by 7 feet (2.1 m). It was hypothesized at the time that this snag was one of many hazards that would be encountered with the lower water levels.[57]

Triton came to rest on a steep underwater slope. The stern sank in 20 feet (6.1 m) of water, while the bow sat on the bottom in 7 feet (2.1 m). The Anderson Steamboat Company carried no insurance on Triton and it was acknowledged at the time that she might not be salvageable.[57] It appears that Triton never sailed again. She is not listed as a company asset as of January 1, 1917, by the Public Service Commission of Washington[58] and drops out of press accounts after her accident.

Ferry service was critical to Lake Washington communities. Real estate interests, trying to sell land on the east side of Lake Washington,[59] and agricultural interests, shipping food from the east side to Seattle, were particularly forceful in their desire for lower ferry rates. The Port Commission of Seattle, newly established in September 1911, responded to these pressures. It placed Proposition 6, a $150,000 bond issue to operate a ferry from Leschi Park to Medina and Bellevue, on the March 1912 ballot. This Port Commission-owned ferry would be in direct competition with the Anderson Steamboat Company.[60] Captain Anderson fought this measure vigorously[61] but lost resoundingly. The bond was approved by 71% of voters.[62]

In order to compete with the King County and Port Commission ferries, and to take advantage of growth on the east side of Lake Washington, Anderson built his biggest ship yet, Issaquah. She was launched on March 7, 1914, from Anderson's shipyard in Houghton and towed to Leschi Park for interior finishing. Her cost was $33,571.[63][64] Anderson designed some features of Issaquah himself, and she reflected his long-term vision for ferries on Lake Washington. Rather than simply a utilitarian transport like the government ferries, Issaquah was also an excursion vessel. Her upper deck featured leather-upholstered seats that could fold up along the walls creating a 30' by 60' hardwood dance floor. The floor was made of birds-eye maple. All summer long Anderson ran "moonlight excursions" from 8 p.m. to midnight with music, dancing, and light refreshments. He charged 50 cents per person and could take hundreds aboard.[65][66]

Anderson owned his dock and terminal facilities at Leschi Park, but the Port Commission decided that these were such a critical link in the local transportation system that they should be owned by the public and available to competing ferry services, including its own. Unable to convince Anderson to sell, the Port Commission began condemnation proceedings to take the land by eminent domain. The matter was finally settled in February 1914. Anderson was paid $20,000 for his land and ferry terminal, and thereafter became a lessee.[67]

The Port Commission launched the steel-hulled ferry Leschi for its new service on December 6, 1913.[68] It undercut the rates of the Anderson Steamboat Company by operating the vessel at a loss. It budgeted $32,470 of expenses for Leschi in 1915 against expected revenues of $18,000.[69] King County's Kirkland ferry, Washington, was also heavily subsidized by tax payers. She lost $31,773 in 1910, and $49,372 in 1911.[70] The private company could not compete. In May 1917, Captain Anderson took all his ships, except Dawn, Issaquah, and Arrow, out of service and announced his intention to close the Anderson Steamboat Company. He said, "The public ferry services are being operated at less than cost. As a result, we are unable to meet their competition and there is nothing left to do but withdraw. The Anderson Steamboat Company will go out of existence. Hereafter, I shall devote my time to my shipbuilding interests."[71] The last of his ships on the lake, Issaquah, was withdrawn on September 30, 1917.[72]

King County takes over the ferries (1917–1922)

When Anderson idled his fleet, residents around the lake complained of the loss of service.[73] Businesses on the east side collapsed for lack of transportation.[74] There was no vessel sailing to Mercer Island that was larger enough to carry an automobile. Public pressure grew, and King County contracted with Anderson Steamboat Company to resume service on Issaquah on November 14, 1917.[75][76] The contract ran through the end of 1917 and paid Anderson $1,875.[77] The contract was not renewed, and in April 1918 Issaquah was sold to the Rodeo & Vallejo Ferry Company for a reported $55,000 to $65,000.[78] She sailed from Houghton for San Francisco Bay on May 20, 1918.[79]

Concern about the operating deficits in the Port Commission's ferry service launched a comprehensive review of whether King County or the Port Commission should run ferries. The report concluded that ferries were logically another form of road or bridge, which was the county's traditional responsibility. Similarly, the tax revenues spurred by the growth of communities benefitting from better ferry service accrued to the county, rather than the Port Commission, allowing the county to fund the operating deficits.[80] On January 1, 1919, the Port Commission transferred its ferry system to King County.[81]

The county commission created the position of Superintendent of Transportation to oversee its enlarged ferry fleet. J.C. Ford, a retired vice-president of the Pacific Coast Steamship Company, was appointed to the position.[82] He died almost immediately upon taking office. On February 24, 1919, Captain Anderson was named as Ford's replacement.[83] He named his longtime partner, Harrie E. Tompkins, Assistant Superintendent of Transportation.[84] Anderson took this position just as his shipbuilding business was suffering financial difficulty.

Anderson's appointment was immediately controversial. There were many transactions where Anderson was a King County executive on one side of a deal and a ship or shipyard owner on the other side. Obvious conflicts of interest arose repeatedly during his tenure. For example, to quell the complaints of poor service, King County leased Dawn, Fortuna, Aquilo, and Atlanta from Anderson to restore the routes that Anderson abandoned in 1917. The one year lease, signed on May 13, 1919, paid Anderson $6,160 for the vessels, which he then ran as Superintendent of Transportation. Fortuna was in need of maintenance, which was done at the county's expense in Anderson's shipyard.[85] The lease contract included an option to purchase the four ships, which was exercised in 1920. King County paid Anderson another $88,000 for the ships he ran as a county executive.[86]

The ferry system cost King County $433,000 in 1920, its second largest expense after roads and bridges. Taxpayers who did not use the ferries objected to paying these costs.[87] County commissioners wrestled with various proposals to reduce the taxpayer subsidy of the ferry service for much of 1921. It considered bids to privatize the system and unanimously rejected them all, including one from Anderson, in March 1921.[88] Finally, on December 8, 1921, King County entered into two contracts that removed it from the ferry business. It entered into a 10-year agreement with Captain Anderson that gave him use of the county's ten ships and its ferry terminals on Lake Washington, and 20,000 barrels of fuel oil. He could keep all the revenues from the ferries, but had to pay for all the expenses. In return, Anderson promised to maintain all the significant routes and not to raise fares. The second contract was signed with Kitsap County Transportation Company, and had similar terms for the county's ferries operating in Elliott Bay and Puget Sound.[89]

Frustration with the ferry system and Anderson's obvious conflicts of interest created a climate of ill-will that toward him. The ferry system lease resulted in requests for a grand jury probe of the transaction in January 1922.[90] On July 10, 1922, John L. Anderson was indicted on four different counts related to his work as Superintendent of Transportation. It was alleged that Anderson spent the county's money recklessly on ships, ferry docks, and landings, believing he would be the private beneficiary of the improvements once the ferry system was leased to him. It was alleged that Anderson and the county commissioners, who were also indicted, conspired to defraud the public by overstating the financial burden of the ferry system and then giving Anderson too good a deal to lease it. The indictment also alleged that the county was overcharged for repairs at Anderson's shipyard. Anderson's brother, Adolph Anderson, and his long-time partner Harrie E. Tompkins, were also indicted on related charges.[91] All three pled not guilty.[92]

Multiple legal proceedings ensued, but by March 30, 1923, all three men were exonerated of all charges. In dismissing the final charge, the presiding judge said, "how it is that a grand jury returned an indictment on evidence of this character I cannot understand."[93]

Lake Washington Ferries (1922–1941)

In 1922, his first year operating Lake Washington Ferries as lessee, Anderson reported a profit of $6,443. This turnaround from the huge losses incurred by the county was due to significant cost cutting. Payroll, fuel, and maintenance costs plummeted. Anderson as a private operator was simply more efficient than he was as a public operator. He explained the difference by saying,

As soon as I began to run the ferries for myself, and was relieved of the orders of the former Board of County Commissioners, I cut salaries and the number of employees...I abolished routes which were losing, but the commissioners dared not abolish because of protests from voters. The whole thing, in a nutshell as the figures show is that I can practice economies and run the ferries on a business basis now which I couldn't do when politics interfered.[94]

County auditors took issue with how some items in Anderson's annual report were characterized and said that his profit was actually $40,516. Ferry users immediately demanded a rate decrease from the then current fare of 10 cents (one-way) and 15 cents (round trip) to 5 cents each way. King County commissioners were appealed to, but analysis of the lease contract showed that while Anderson had no power to raise rates, he had the sole power to reduce them. Whatever the profit number, 1922 showed that the county could avoid a large financial burden while still providing its citizens with a viable ferry system. Anderson carried 1,225,374 passengers that year.[95][96]

Anderson reduced fares for cars in 1923. One way fares for light, medium, and heavy cars were $0.50, $0.60, and $0.80 cents respectively. In May 1923 he introduced round-trip rates of $0.75, $0.90, and $1.20 respectively.[97] While surely these lower fares calmed some citizen discontent about his profits, it is also true that cars were a growing competitive challenge to ferries. Not only were the number of cars growing, but better roads and bridges made their use more attractive. The first bridge linking Mercer Island to the mainland was opened on November 10, 1923. The paving of the boulevard around Lake Washington was also completed in 1923. Ferry patrons now had choices, and despite the lower rates there were 37,710 fewer cars on board in 1923 than in 1922. Ferry system revenues fell, but oil prices fell faster, allowing Anderson to report a profit of $8,389 for 1923.[98][99]

The rise of the automobile drove the Lake Washington ferry system into a deficit in 1925. Anderson lost $2,162 on revenue of $173,698. His fleet carried 1,056,308 passengers and 200,941 vehicles.[100] Fuel costs fell in 1926, swinging the ferry system to a profit of $5,827, but traffic fell by more than half. There were 456,512 foot passengers and 82,636 vehicle crossings.[101] By December 1927, the public's dependence on the Lake Washington ferry system had fallen to such an extent that King County was able to extend Anderson's lease by twenty years, to 1951, without significant comment.[102] In November 1937 Anderson returned Atlanta and Aquilo to King County, since he had no further need of these small passenger-only ships.[103]

A floating bridge across Lake Washington was proposed as early as 1921, but had no source of financing until 1937, when funding from the Public Works Administration became available. Construction began in December 1938.[104] Potential buyers of bridge bonds demanded the elimination of Anderson's ferry service altogether. This would force all travelers to pay the bridge toll, maximizing the revenue to pay back the bonds. In December 1938, the King County Board of Commissioners cancelled Anderson's lease on the ferry system effective January 1, 1939. Anderson, in turn, filed a claim of $213,000 of anticipated damages with the Washington Toll Bridge Authority. He said, "We are not just going to step out of the picture and let the county take us over without a fight. There must be some justice in this".[105]

On December 30, 1938, Anderson was granted a temporary restraining order to prevent the county from breaking the lease.[106] Three-way negotiations ensued between Anderson, King County, and the Washington Toll Bridge Authority. A settlement was reached on February 4, 1939. Two of the three King County commissioners only agreed to the deal after they were told that the bond issue for the floating bridge would fail if they did not get rid of Anderson's ferry competition. Anderson got a $35,000 cash payment in return for abandoning the Leschi-Medina and Leschi-Mercer Island routes when the bridge opened. The county would stop its efforts to break the lease and Anderson would continue to operate the Madison Park-Kirkland route. Anderson contended that the cash payment was only a return of money he had invested in the fleet in anticipation of operating it for the rest of the lease term. He claimed that he got nothing for future lost profits.[107]

The Lacey V. Murrow Memorial Bridge was opened on July 2, 1940,[108] but relations between King County and Anderson remained testy. On his one remaining route across the lake, Madison Park to Kirkland, Anderson lowered the fare for cars from 50 cents to 25 cents, equal to the toll rate on the new bridge.[109] Anderson closed the ferry routes required in the settlement agreement when the bridge opened and reconfigured his fleet. On July 12, 1940, Anderson terminated his lease on Washington, and returned her to the county. He also announced his intent to return Mercer in August.[110] The county auctioned Washington for $2,350 and Mercer for $1,850 to a salvage firm.[111] The ill will associated with the $35,000 bridge settlement hung over these ships and the county investigated whether Anderson had breached his lease agreement by failing to maintain the ferries in good condition.[112]

In 1940, the last full year that Anderson operated the Lake Washington ferry system, it lost $7,423 on revenue of $102,966. There were 658,796 foot passengers and 156,403 vehicles carried. Revenue and traffic decreased substantially because of the discontinued routes.[113]

Anderson Shipbuilding (1906–1920)

J. F. Curtis began building boats in his Houghton backyard in 1884.[114] He built nine steamers there, including Anderson's first command, C. C. Calkins, and the area became a small hub of shipbuilding on Lake Washington.[115] In 1904 Curtis' property was purchased by Captains George Bartsch and Harrie E. Tompkins. With the merger of Bartsch & Tompkins Transportation Company and Anderson Steamboat Company in 1906,[37] the shipyard began to be referred to as the Anderson Shipbuilding Company. It does not, however, appear to have had a separate legal existence. Contemporaneous accounts often refer to it as the "shipbuilding department" of the Anderson Steamboat Company.

Anderson Shipbuilding Company (1906–1917)

The shipyard was a modest operation at first, catering primarily to the needs of Anderson Steamboat Company. The shipyard was basic; scaffolding, hand tools, and a mule-powered windlass.[116] It was small enough that the rear half of the property was converted into an equally modest tourist attraction, Atlanta Park. This was a picnic ground and dance pavilion served by Anderson Steamboat Company excursions during the summer from 1908 to 1916. Atlanta Park was sacrificed to the growth of the shipyard when it expanded in 1917.[117]

By 1908 Anderson started building his own ships at the Houghton yard. He had small ways installed, on which Atlanta was built in 1908, and a second ways, allowing Triton and Aquilo to be built simultaneously in 1909.[118][49] By 1910 a small tramway had been built to haul heavy loads between shops and the ways.[116]

The shipyard also built for others. On January 16, 1909 Rainier was launched.[119] She was the private yacht of Andrew Hemrich, president of Seattle Brewing and Malting Company, the producer of Rainier Beer.

In 1913 Anderson began building Issaquah, his largest construction project to that point. She was a double-ended ferry with capacity for 600 passengers and 40 vehicles. The shipyard had progressed significantly in its capabilities, including cranes and steam-power. Issaquah was launched on March 7, 1914.[63][64] The keel for Dawn was laid immediately after the launch of Issaquah.[54]

Buoyed by the successful launch of Issaquah, Anderson bid on and won the contract to build Lincoln, a new steel-hulled ferry for King County.[120] His price for the project was $91,599. Lincoln, too, was a success and was launched on December 12, 1914 [121]

The Anderson shipyard built City of Bothell for the Bothell Transportation Company, and launched her in May 1914.[120] In anticipation of a significant rise in summer excursion traffic, Anderson Steamboat Company bought her in May 1915. She came back to the shipyard and underwent a refit before being rechristened Swan.[122]

Buoyed by the successful launches of Issaquah and Lincoln in 1914, Anderson sought to build larger ships. Since larger ships could not reach the sea from his Houghton shipyard, he leased land on Harbor Island in Seattle on the East Waterway from the Oregon-Washington Railroad.[123] Here he established a second shipyard. The first vessel launched from this yard was the ferry Bainbridge, built for the Eagle Harbor Transportation Company. She was launched on April 28, 1915, at a cost of approximately $42,000.[124]

On November 9, 1914, Anderson Shipbuilding was awarded a contract by the United States Lighthouse Service to build the Lighthouse Tender Rose. It substantially underbid more established shipyards, offering to build the ship for $87,500.[125] Construction on Rose began immediately after Bainbridge was launched. On February 19, 1916 Rose was launched successfully, and was quickly accepted by the Lighthouse Service.[126] There are no reports of other ships built by Anderson at the Harbor Island facility. The opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal in 1917 allowed him to consolidate all his shipbuilding activities in Houghton.

Anderson Shipbuilding Corporation (1917–1920)

Anderson went out of the ferry business in 1917 in the face of competition from government-owned ships. This withdrawal coincided with new opportunities for his shipyard. On May 8, 1917, the Hiram Chittenden Locks opened to boat traffic. Prior to this connection, only shallow-draft vessels that could navigate the Black River could reach Puget Sound from Lake Washington. Now large, ocean-going ships could be built in Lake Washington and reach the sea. At the same time, World War I created significant demand for new ocean-going ships. The need for new ships was driven in part by losses to U-boats and, after the United States joined the conflict in April 1917, the need to support American military efforts in Europe. In April 1917 Anderson said, "It would simply be impossible for the shipbuilding industry to handle the enormous volume of business now offering."[127]

Anderson sensed a business opportunity to build ocean-going ships at his shipyard. In early 1917, Anderson Shipbuilding Company was incorporated with a capital stock of $1 million. Shortly after, on April 13, 1917, Anderson brought in allies, completing a three-way merger with the shipbuilding interests of D. H. Gray & Company, and R. F. Guerin.[128] The merged entity was renamed Anderson Shipbuilding Corporation, and had Anderson as its president.[129] Harrie E. Tompkins, Anderson's long-time partner, was night manager of the shipyard.[130] The merger brought new investment to the shipyard, most prominently, the construction of two new ways. These new facilities, added to the existing two ways, would allow the construction of four vessels at the same time.

Anderson also solicited repair and conversion work. The barge Bangor was hauled out and converted into four-masted schooner, the first ocean-going ship to be hauled out in Lake Washington.[131] The King County ferries Washington, Lincoln, and Leschi were hauled out for maintenance, as were the retired ferries of Anderson's own fleet.[132][133]

By July 1917, Anderson had laid the keels for two 3,250 ton ocean-going steamships. They were 270 feet (82 m) long and cost $400,000 each, clearly the largest and most expensive ships ever built on Lake Washington.[134] The first, Osprey, was launched on July 3, 1918. Five-thousand people in the shipyard and in boats surrounding it watched the launch of the first ocean-going ship ever to be built on Lake Washington.[135] The second ship, Oleander, was launched two months later on September 4, 1918.[136] Both ships were sold to the French government, with Osprey rechristened General Pau after the sale.[137]

On December 5, 1917, Hannevig Brothers of Norway signed a contract for two ocean-going ships priced at $380,000 each.[138][139] The United States Shipping Board ordered fourteen ships. It appeared that Anderson Shipbuilding would prosper. The end of World War I, however, brought a new reality. In the fall of 1918 Anderson visited New York, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia. He came back concerned. He said, "The signing of the armistice has caused much uncertainty in the wooden shipbuilding industry and no one down East seems to know just what the future has in store for it". The contracts for the fourteen vessels for the United States Shipping Board were cancelled.[140]

Despite the goodwill surrounding the launches of Osprey and Oleander, they resulted in a flurry of lawsuits and other legal actions lasting well into the 1920s. Anderson contracted to have the ships completed in ten months. It took a year to launch them and longer still to install their machinery, and repair defects. Costs to finish the ships exceeded budget and Anderson lost money on the deal. The Scandinavian American Bank of Seattle, one of Anderson's long-time financial partners, guaranteed the performance of the contracts and in May 1922 was ordered to pay $167,363 the purchaser.[141][142]

The Hannevig contract also ran into trouble. In order to complete the over-budget Osprey and Oleander, Anderson used cash, at least some of which was paid to fund the Hannevig ships. There were assertions at the time that the Scandinavian American Bank pressed for this in order to minimize the cost of its performance guarantee on Osprey and Oleander. Given the cost overruns on his first two ocean-going ships, Anderson was unable to obtain a performance bond on the Hannevig contract. He was forced to deposit $75,000 of Hannevig's initial payment in a trust account, depriving the shipyard of needed cash. By February 1919, Anderson Shipbuilding was so short of cash that it notified Hannevig that it could not complete the contract without additional funding. In April 1919, construction on the ships stopped when they were 65% complete.[142][139] The partially completed hulls were purchased by John L. McLean. McLean contracted with J. H. Price Construction Corporation to finish the work, since Anderson could not. Anderson, in turn, leased the shipyard to Price.[143][144] Price finished the ships and launched Donna Lane and Muriel in the first half of 1920.[145]

Anderson lost money on his four largest shipbuilding contracts and was out of cash. Further, demand for wooden ocean-going ships had disappeared after the armistice. In early 1921 Anderson sold the shipyard to Lake Union Drydock and Machine Works Company. It, in turn, sold the facility to Lake Washington Shipyards, on October 7, 1923.[146] For the rest of his life, Anderson would order new ships and contract for repairs in shipyards, particularly his old plant in Houghton, but he would never own a shipbuilding business again.

Kitsap County Transportation Company (1925–1935)

When King County left the ferry business in 1922, the Lake Washington fleet was leased to Anderson, and the Elliott Bay and Puget Sound routes were leased to Kitsap County Transportation Company. Captain Lyman Hinckley, president of the Kitsap County Transportation Company, died suddenly of a heart attack on December 4, 1924.[147] On March 21, 1925, an investment group led by Captain Anderson purchased Hinkley's controlling interest in the company. Anderson assumed the presidency and immediate control of the company's operations. At the time of the acquisition, Kitsap County Transportation Company employed two ferries leased from King County, and eight other ships. Its routes from Seattle ran to Bainbridge Island, Vashon Island, and the mainland of Kitsap County. It carried 649,120 passengers in 1924, the year before Anderson took control, generating $234,348 in revenue.[148] In discussing the acquisition Anderson said, "The beauties of the Olympic Peninsula are drawing a great number of persons every year, and the ferries afford such a savings of time and distance to motorists that traffic is certain to be enlarged with the increase in popularity and the growth of the districts across the Sound".[149]

Anderson embarked on an aggressive expansion plan. Within days of taking control of the company, he ordered the construction of Kitsap, the largest ferry north of San Francisco. She could carry 90 cars and 1,500 passengers. He financed the construction with a $135,000 bond.[148] The new ship earned her keep; the company carried 102,274 cars in 1927 compared to 81,389 in 1926. In October 1927, Kitsap County Transportation Company grew by merger, purchasing Eagle Harbor Transportation Company for a reported $50,000. This deal brought the steamers Bainbridge and Speeder, as well as dock space in Winslow.[150] A four-way merger in May 1928 added six more ships and several new routes to Anderson's firm.[151] On May 19, 1928, Kitsap County Transportation Company launched a new Bainbridge, a car ferry even larger than Kitsap. Anderson's niece, Selma Louise Anderson, christened the ship.[152] Anderson had Vashon, his biggest ferry yet, built to increase service to Vashon Island. She was launched May 10, 1930.[153] As the economy suffered in the Great Depression, this was the last major vessel he built.

Seeking deeper financial backing, Anderson signed a deal to sell Kitsap County Transportation Company to W. B. Foshay Company on April 8, 1929, for $1,075,000.[154] Anderson touted the benefits of, "unlimited financial resources" for the development of the companyl.[155] Various regulatory clearances were required to close the deal. While these approvals were pending, the stock market crashed on Black Friday. W. B. Foshay went bankrupt just days later in November 1929.[156] The deal fell through.

Kitsap County Transportation Company, and Puget Sound Navigation Company, known to the public as the "Black Ball Line", sparred continually. In 1930, Anderson opened a new front in this competition. Captain William E. Mitchell ran Anderson's ferry service between Seattle and Bremerton, called the Washington Line. He purchased General Frisbie, a surplus passenger ferry from the San Francisco Bay. She was renamed Commander by her new owners. The ship was surplus because she had almost no ability to carry cars. On the Washington Line, however, this deficit was less important since hundreds of workers from Seattle commuted to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton every day.[157] The ferry dock in Bremerton was within walking distance of the naval shipyard, so the workers did not need a car ferry.[158]

Commander's owners announced a round-trip price between Seattle and Bremerton of $0.60, undercutting Black Ball's $0.80 rate. The newspapers portrayed this as a "rate war" with "battle lines drawn". The board of Puget Sound Navigation Company, chose not to match the lower rate.[159] Instead, it intervened with the Washington Department of Public Works, which regulated ferry service, in April 1930 seeking to prevent Commander from operating. The case was fought up to the Washington Supreme Court which ruled in favor of the challengers on April 2, 1931.[160] Anderson's new ship began sailing shortly thereafter, and the Black Ball Line never met her lower price.

By the early 1930s ferry workers were largely organized into unions. In February 1935, the Masters, Mates, and Pilots Association, and the Ferryboatman's Union began negotiating with the Washington Ship Owners Association for a new contract. The unions wanted an eight-hour work day, and to be paid for all the hours they worked. Meeting these demands would significantly increase payroll costs, and in the face of the Great Depression and the tough competition on Puget Sound, the owners balked. In early November 1935, crews began to walk off and most ferries were tied up.[161]

The unions were strategic as to which ferries they allowed to operate. They wanted to pressure the owners without turning the public completely against them. At the beginning of the strike, the only Kitsap County Transportation ferry that was allowed to operate was Winslow, which became Bainbridge Island's only direct connection to Seattle.[162] Later, Commander was allowed to resume service. This had the effect of allowing Puget Sound Naval Shipyard employees to get to work, while cutting off car ferry service to Bremerton, which only the Black Ball ships provided.[163][164]

The strike became a political issue. The King County Board of Commissioners threatened to revoke Anderson's lease agreement unless Kitsap County Transportation Company resumed service to Vashon Island.[165] On that same day, November 14, 1935, Anderson bowed out of the struggle. He struck an agreement to merge Kitsap County Transportation Company into Puget Sound Navigation Company. Anderson's said that the strike forced him into the merger. He did not have the cash to fight on.[164]

Independent Ferry Company (1929–1930)

Passenger and auto service from Edmonds to the inner harbor at Victoria, B.C., on City of Victoria was inaugurated on June 16, 1928. Prior to her repositioning to Puget Sound, the ship ran between Norfolk and Baltimore as Alabama.[166] She completed two round-trips to Victoria per day. The service was entirely driven by tourists, and ran only in the summer months.

Anderson created the Independent Ferry Company to charter City of Victoria for the summer 1929 season. The charter contract included an option to buy the ship, the largest American-flagged ferry in Puget Sound waters.[167] She reflected Anderson's belief in the nautical excursion business. The ship had a glass-enclosed observation room, an orchestra for dancing, and over one hundred staterooms and suites, some of which had bathtubs.[168] City of Victoria's summer 1929 season was a great success. The onset of the Great Depression put a damper on the 1930 season, however. When the ship was idled for the winter in September 1930, Anderson said, "While traffic has not been as heavy this summer as we anticipated...we are confident that tourist traffic will regain its former volume in another year, and we shall be ready to resume the run next summer.[169] It never happened. The ship and the Independent Ferry Company drop out of press accounts in 1930. City of Victoria's Federal registry data shows that Anderson never executed his purchase option on the ship.

Anderson Water Tours Company (1926–1941)

_in_1931.jpg.webp)

Captain Anderson ran excursion tours on Lake Washington for his entire career starting at least as early as his ownership of Quickstep in the 1890s. In June 1922, Anderson started a new excursion route. Atlanta ran two-hour tours from Leschi Park, through the Hiram Chittenden Locks into Puget Sound, finally docking in downtown Seattle at the foot of Marion Street.[170] This route, "The Canal Tour", was a commercial success. He formed Anderson Water Tours Company in 1926 to exploit this and other tourism opportunities that were beyond the scope of his lease with King County.

The Canal Tour only operated in the pleasant summer months, typically starting in June and ending in September. In the summer of 1926, Atlanta sailed from Leschi Park at 11 a.m., and sailed back from Elliott Bay at 2:30 p.m. The fare was $1.50 per person.[171] Some time in 1933 or 1934, Anderson purchased Vashona from Vashon Navigation Company.[172] In the spring of 1935, Anderson sent Vashona to the shipyard for refurbishment. She emerged as Sightseer, a purpose-built tour boat with seating for 300 passengers. The new boat took over the Canal Tour. Atlanta became a reserve boat available for special holiday events, and as a back-up, until she was returned to King County in November 1937.[173][174] Sightseer ran this excursion every summer for the rest of Anderson's life.[175]

In 1938 or 1939, Anderson purchased the steam yacht Mercer, which Anderson Water Tours used to run excursion trips around Mercer Island.[176][177]

In June 1942, Harrie E. Tompkins, who took over management of Anderson Water Tours after Anderson's death, made the decision to suspend the tours for the duration of World War II.[178] In fact, Anderson Water Tours never sailed again. In 1946, Emilie Anderson sold Sightseer to Gray Line Tours. On June 23, 1946, Gray Line Tours recommenced the Canal Tour that John Anderson pioneered decades earlier.[179][180]

Decline and death (1941)

Captain Anderson was actively involved in his businesses until he had a heart attack in early May, 1941. He was admitted to Swedish Hospital where he died about a week later on May 18, 1941. He is buried at the Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Seattle. He was succeeded in operating King County Ferries and Anderson Water Tours by his long-time partner, Captain Harrie E. Tompkins.[181] Anderson's estate was valued at $92,316. The largest asset was stock in Puget Sound Navigation Company, which he obtained in 1935 in exchange for his interest in Kitsap County Transportation Company. The estate also included the two Anderson Water Tours Company ships, Mercer and Sightseer.[182]

Personal life

John Anderson married Emilie K. Matson on September 28, 1895, at the Diller Hotel.[183] She was a native of Meriden, Illinois, who had come to Seattle in 1884[2] The couple had no children. Emilie died on January 25, 1959.[184]

John's brother Adolph, who lived near John and Emilie in Seattle, had his own maritime business. His was focused on tug and barge operations. John helped him start his business. The tug C. F. was bought by Anderson Steamboat Company on April 3, 1907, for use towing log rafts to mills on Lake Washington.[185][186] When John sold her to Adolph, she became the first tug in his fleet.[187] Adolph's tug company appears to have been largely independent of John's ventures. John did use Adolph's services when he needed a grounded ferry pulled off the beach and for other towing needs, a relationship that involved Adolph in the 1922 indictments. Adolph had three children, Selma, John A., and Clarence.[188] He predeceased his older brother, dying on January 4, 1936.[189]

John's brother Albert was also a mariner. In the 1910 census he listed his occupation as a mate on a schooner.[190] In 1930 he was living in Ketchikan, Alaska, working as a halibut fisherman.[191]

John's sister, Clara Mattson, also lived in Seattle. She had five children, Olga, Tage, Clara, Frank, and Adolph. Clara passed away in 1948.[192]

As of the 1910 census John and Emilie lived at 112 Erie Avenue, just north of Leschi Park. They lived with John's brother, Albert.[190] In June 1928, Anderson was issued a building permit for a $10,000 home at 503 Lakeside Avenue, just south of Leschi Park.[193] The family moved in 1929. As of the 1930 census, they lived with Emilie's brother Milard F. Matson[194] John and Emilie lived in this home until their deaths in 1941 and 1959.

John was active in numerous local clubs and community organizations. He belonged to the Nile Temple of the Shrine, Seattle Chamber of Commerce, Transportation Club, Swedish Club, Swedish Businessmen's Association, Kirkland Service Club, among others.[181]

References

- ↑ "John Laurentius Anderson". www.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2020-03-27.

- 1 2 3 Barley, Clarence (1916). History of Seattle. Vol. 3. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. pp. 423–424.

- 1 2 3 4 "Master Of Lake Began As Deckhand". Seattle Daily Times. October 25, 1914.

- 1 2 "A Steamer Burned". Daily Intelligencer. September 13, 1894.

- ↑ "Marine News". Daily Intelligencer. September 27, 1894.

- ↑ "Steamer Quickstep". Seattle Daily Times. January 4, 1897.

- ↑ "A New Lake Steamer". Daily Intelligencer. January 24, 1897.

- ↑ "Steamer Lady of The Lake". Seattle Daily Times. June 26, 1897.

- ↑ "Puget Sound Shipping". Daily Intelligencer. August 2, 1897.

- ↑ "Local News". Mason County Journal. January 7, 1898.

- ↑ "Puget Sound Shipping". Daily Intelligencer. March 7, 1898.

- ↑ Merchant Vessels of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1902. p. 408.

- 1 2 Dyer, Alfred W. (June 1928). "A Transportation Builder". Railway and Marine News: 6–9 – via Puget Sound Marine Historical Society.

- ↑ "G. V. Johnson, Pioneer Shipbuilder, Is Dead". Seattle Daily Times. May 1, 1926.

- ↑ "New Lake Steamer". Seattle Daily Times. June 29, 1899.

- ↑ "Door Of Hospitality Stands Open To Editorial Guests". Daily Intelligencer. July 12, 1899.

- ↑ "Changes of Masters". Seattle Daily Times. October 28, 1899.

- ↑ "Bills Of Sale". Seattle Daily Times. August 25, 1900.

- ↑ "Inland Flyer Flies". Oregonia. September 6, 1898.

- ↑ "Local Brevities". Dalles Weekly Chronicle. September 14, 1898.

- ↑ "Local Brevities". Dalles Weekly Chronicle. December 17, 1898.

- ↑ "Sale Of The Inland Flyer". Daily Intelligencer. December 25, 1900.

- ↑ "Eastside Boat Building". Oregonian. December 5, 1900.

- ↑ "Made A Record Run". Seattle Daily Times. February 11, 1901.

- ↑ "Lake Whatcom". Seattle Daily Times. March 31, 1903.

- ↑ "Bills Of Sale". Seattle Daily Times. April 5, 1903.

- ↑ "Marine Notes". Seattle Daily Times. March 12, 1900.

- ↑ "Saw The Big War Vessels". Seattle Sunday Times. June 15, 1902.

- ↑ "Changes Of Masters". Seattle Daily Times. March 1, 1903.

- ↑ "Strs. Cyrene and Xanthus". Seattle Daily Times. July 26, 1903.

- ↑ "Marine Railway Built". Seattle Daily Times. December 23, 1903.

- ↑ "Launching On Lake". Seattle Daily Times. June 14, 1904.

- ↑ "New Steamer For Lake Washington". Seattle Daily Times. July 10, 1904.

- ↑ "Steamer Mercer". Seattle Daily Times. August 6, 1904.

- ↑ "Steamer Needed On Lake". Seattle Daily Times. October 29, 1905.

- ↑ "Seattle Daily Times". December 1, 1906.

- 1 2 "Consolidate Lake Boats". Seattle Daily Times. October 26, 1904.

- ↑ "Can Run Its Ferry". Seattle Daily Times. August 8, 1902.

- ↑ "Bills of Sale". Seattle Daily Times. January 6, 1907.

- ↑ "Companies Merge Their Lake Craft". Seattle Daily Times. November 27, 1906.

- ↑ "Customs Penalty Confirmed". Seattle Daily Times. July 25, 1907.

- ↑ "Anderson Adds To His Fleet". Seattle Daily Times. April 14, 1907.

- ↑ "Lake Washington Ferry Planks Unsound". Seattle Daily Times. March 15, 1970.

- ↑ "Ferry Sinks". Seattle Star. May 20, 1907.

- ↑ "Ferry Loses Much Money". Seattle Daily Times. December 2, 1909.

- ↑ "Problem Solved By Private Concern". Seattle Daily Times. March 4, 1908.

- ↑ "McKenzie Still Opposes Anderson's Ferry Bill". Seattle Daily Times. March 27, 1911.

- ↑ "Wharf Leased By Park Board". Seattle Daily Times. May 25, 1909.

- 1 2 "New Steamboat Which Plies To Exposition". Seattle Daily Times. May 30, 1909.

- ↑ "Aquilo Appeal Not Sustained". Seattle Daily Times. July 28, 1909.

- ↑ "Anderson Company Maintains Monopoly". Seattle Daily Times. November 14, 1909.

- ↑ "Fire Destroys Big Excursion Boat Wildwood". Seattle Daily Times. September 20, 1910.

- ↑ "Lake Boat Swept By $5,000 Blaze". Seattle Daily Times. February 13, 1914.

- 1 2 "Constructing Craft To Replace Urania". Seattle Daily Times. May 19, 1914.

- ↑ "Fire On Lake Is Cause For Alarm". Seattle Star. July 29, 1913.

- ↑ "Fire Destroys Old Passenger Vessel". Seattle Daily Times. July 29, 1913.

- 1 2 "Triton Is First Wreck In Lake". Seattle Daily Times. September 25, 1916.

- ↑ Eighth Annual Report of the Public Service Commission of Washington to the Governor. Olympia, Washington. 1918. p. 179.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Ferry Is To Boost Real Estate, He Says". Seattle Daily Times. March 1, 1912.

- ↑ "Lake Ferry Indorsed (sic) by Automobile Club". Seattle Daily Times. February 10, 1912.

- ↑ "About Port Commission Proposition No. 6". Seattle Daily Times. March 3, 1912.

- ↑ "Completed Returns Certified By Case". Seattle Daily Times. March 8, 1912.

- 1 2 "New Ferry Goes Into Washington". Seattle Daily Times. March 8, 1914.

- 1 2 Report Of The Public Service Commission Of Washington To The Governor. Olympia, Washington. 1918. p. 179.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Expect New Ferry To Open Territory". Seattle Daily Times. February 16, 1914.

- ↑ "Grand Moonlight Excursions". Seattle Daily Times. June 20, 1914.

- ↑ "Port Buys Dock Site". Seattle Daily Times. February 14, 1914.

- ↑ "Ferry Leschi Goes Into Waters Of Lake". Seattle Daily Times. December 7, 1913.

- ↑ "Port District Cuts Expenses". Seattle Daily Times. September 6, 1914.

- ↑ "Kirkland Rises Up In Ferry's Defense". Seattle Daily Times. August 25, 1912.

- ↑ "Anderson Steamships To Be Sold". Seattle Daily Times. May 27, 1917.

- ↑ "Wants Leschi's Route Extended To Newport". Seattle Daily Times. October 4, 1917.

- ↑ "Ferry Users Want More Service From Port". Seattle Daily Times. January 18, 1918.

- ↑ "Auction". Seattle Daily Times. May 12, 1918.

- ↑ "County Tries To Help Commuters". Seattle Daily Times. October 29, 1917.

- ↑ "Issaquah On Lake Route For County". Seattle Daily Times. November 14, 1917.

- ↑ "Ferry Service On Lake To Be Resumed". Seattle Daily Times. November 7, 1917.

- ↑ "Issaquah Acquired By San Francisco interests". Seattle Daily Times. April 3, 1918.

- ↑ "Lake Ferry Starts On Voyage To Golden Gate". Seattle Daily Times. May 20, 1918.

- ↑ "County Board Held Proper To Run Ferries". Seattle Daily Times. April 3, 1918.

- ↑ "Contract Signed For Taking Over Ferries By County". Seattle Daily Times. October 31, 1918.

- ↑ "J.C. Ford Is Appointed Head Of County Ferry System". Seattle Star. January 15, 1919.

- ↑ "Anderson Ferry Manager". Seattle Daily Times. January 24, 1919.

- ↑ "Graft Charged 10 Seattle Men". Oakland Tribune. July 11, 1922.

- ↑ "County Leases Ferries". Seattle Daily Times. May 14, 1919.

- ↑ "County To Buy Boats". Seattle Daily Times. March 16, 1920.

- ↑ "Editorial". Seattle Daily Times. August 30, 1921.

- ↑ "Ferry Bonus Bids Refused By Board". Seattle Daily Times. August 30, 1921.

- ↑ "County Leases All Its Ferries". Seattle Daily Times. December 9, 1921.

- ↑ "Ask Grand Jury Probe". Seattle Daily Times. January 7, 1922.

- ↑ "Ten Indicted For Theft". Seattle Daily Times. July 11, 1922.

- ↑ "Four Plead Not Guilty". Seattle Daily Times. July 19, 1922.

- ↑ "Captain Anderson Exonerated". Seattle Daily Times. March 30, 1923.

- ↑ "Anderson Explains Profits". Seattle Daily Times. March 13, 1923.

- ↑ "Ferry Fare In Lease". Seattle Daily Times. March 12, 1923.

- ↑ "Ferry Earns Profit As Private Venture". Seattle Daily Times. March 9, 1923.

- ↑ "Reduction In Fares". Seattle Daily Times. May 31, 1923.

- ↑ "Mercer Island Celebrates Opening Of Bridge". Seattle Daily Times. November 11, 1923.

- ↑ "Ferries Make Profit". Seattle Daily Times. February 1, 1924.

- ↑ "King County Ferries Show $2,162 Deficit". Seattle Daily Times. January 31, 1926.

- ↑ "Lake Washington's Ferries Show Profit". Seattle Daily Times. January 29, 1927.

- ↑ "As A Matter Of Fact". Seattle Daily Times. July 9, 1928.

- ↑ "Ferries Given Back". Seattle Daily Times. November 27, 1937.

- ↑ "Homer Hadley formally proposes a concrete pontoon floating bridge across Lake Washington on October 1, 1921". www.historylink.org. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "Anderson Plans Contract Test". Seattle Daily Times. December 14, 1938.

- ↑ "Restrainer Granted By Batchelor". Seattle Daily Times. December 30, 1938.

- ↑ "County Agrees To Drop Fight Over Ferries". Seattle Sunday Times. February 5, 1939.

- ↑ "Lake Bridge Opens With "Christening"". Seattle Daily Times. July 2, 1940.

- ↑ "Lake Boats Cut Rate On Autos". Seattle Daily Times. February 16, 1940.

- ↑ "Anderson Ends One Ferry Lease". Seattle Daily Times. July 12, 1940.

- ↑ "Two Lake Ferries Sold By County To Salvage Firm". Seattle Daily Times. October 28, 1940.

- ↑ "County Orders Ferry Payment". Seattle Daily Times. July 31, 1940.

- ↑ "Loss On Ferries Laid To Bridge". Seattle Daily Times. February 1, 1941.

- ↑ "Lake Washington Shipyards (Kirkland)". www.historylink.org. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- ↑ "Rites For Pioneer Pilot". Seattle Daily Times. October 1, 1918.

- 1 2 McCauley, Matthew W. (2017-10-16). Early Kirkland. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-6327-1.

- ↑ "Lake Washington Excursions". Seattle Daily Times. June 13, 1908.

- ↑ "Lake Washington Excursion Boat Launched Yesterday". Seattle Daily Times. May 29, 1908.

- ↑ "Rainier Launched At Houghton". Seattle Daily Times. January 17, 1909.

- 1 2 "New Ferry Will Be 155 Feet Long". Seattle Daily Times. May 19, 1914.

- ↑ "New Lake Ferry Almost Ready". Seattle Daily Times. December 9, 1914.

- ↑ "Lake Boat Bought For Tourist Trade". Seattle Daily Times. May 31, 1915.

- ↑ "New Shipbuilding Firm Is Formed". Seattle Daily Times. November 8, 1914.

- ↑ "Bainbridge Takes Dip Among Cheers". Seattle Daily Times. April 29, 1915.

- ↑ "Tender Rose To Be Built Here". Seattle Daily Times. November 7, 1914.

- ↑ "Lighthouse Tender Rose Take Baptismal Plunge". Seattle Daily Times. February 19, 1916.

- ↑ "Offers Of Shipbuild Contracts Aggregating $32,000,000 Refused". Seattle Daily Times. April 15, 1917.

- ↑ "Shipyards Plan To Start Building". Seattle Daily Times. April 14, 1917.

- ↑ "Shipbuilding Notes". International Marine Engineering: 79, 279. February 1917.

- ↑ "Lake Washington Is Preparing For Launching". Seattle Daily Times. June 11, 1918.

- ↑ "Barge Called To Sea As Schooner". Seattle Daily Times. January 20, 1918.

- ↑ "Lake Washington Is Preparing For Launching". Seattle Daily Times. June 11, 1918.

- ↑ "Lincoln To Go Back On Old Run". Seattle Daily Times. April 12, 1919.

- ↑ "To Lay Keel For New Wooden Ship". Seattle Daily Times. July 4, 1917.

- ↑ "Dream Comes True s Steamer Osprey Races Into Lake Washington". Seattle Daily Times. July 4, 1918.

- ↑ "Anderson Plant Launches Vessel". Seattle Daily Times. September 5, 1918.

- ↑ "4 Launchings In Next Two Weeks". Seattle Daily Times. March 29, 1919.

- ↑ "Hannevigs Order Two More Wooden Ships". Seattle Daily Times. December 6, 1917.

- 1 2 "Skibsaktieselskapet Bestum III v. Duke, 131 Wash. 467, 230 Pac". courts.mrsc.org. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- ↑ "Captain Anderson Finds Industry Uncertain". Seattle Daily Times. December 22, 1918.

- ↑ "$550,000 Suit Is Filed". Seattle Daily Times. April 11, 1922.

- 1 2 United States Norway Arbitration Under The Special Agreement. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1922. pp. 354–355.

- ↑ "Price Co. Leases Anderson Plant". Seattle Daily Times. December 31, 1919.

- ↑ "New Ship Industry For Seattle". Seattle Daily Times. October 5, 1919.

- ↑ "Launched In Lake Washington". Seattle Daily Times. June 27, 1920.

- ↑ "Shipyard On Lake Sold". Seattle Daily Times. October 7, 1923.

- ↑ "Lyman Hinckley Dies". Seattle Daily Times. December 5, 1924.

- 1 2 "New Issue To Be Offered". Seattle Daily Times. May 18, 1925.

- ↑ "Buys Steamboat Line". Seattle Daily Times. May 22, 1925.

- ↑ "Kitsap Firm Buys Eagle Harbor Co". Seattle Daily Times. October 7, 1927.

- ↑ "Ferryboat Lines Are Consolidated On Puget Sound". Seattle Daily Times. May 22, 1928.

- ↑ "Big Automobile Ferry Launched From Lake Yard". Seattle Daily Times. May 20, 1927.

- ↑ "Big Crowd Sees New Vessel Go Down The Ways". Seattle Daily Times. May 11, 1930.

- ↑ "Receiver Loses In Foshay Suit". Seattle Daily Times. December 5, 1929.

- ↑ "Big Development Of Sound Ferry Lines Forseen". Seattle Daily Times. May 9, 1929.

- ↑ "W. B. Foshay Co. Files Petition In Bankruptcy". Seattle Daily Times. November 1, 1929.

- ↑ "Bremerton Asks Ferry Changes". Seattle Daily Times. March 24, 1933. p. 16.

- ↑ Both the shipyard and ferry terminal are important points in Bremerton, so most area maps will show them.

- ↑ "Ferry Rate War Meeting Called By Black Ball". Seattle Sunday Times. March 9, 1930. p. 26.

- ↑ "Ferry Prepared For Service On Bremerton Run". Seattle Daily Times. April 3, 1931. p. 13.

- ↑ "Ferry Owners Explain Stand". Seattle Daily Times. November 8, 1935.

- ↑ "Union Predicts Strike Peace". Seattle Daily Times. November 8, 1935.

- ↑ "Cross-Sound Auto Trucks Blocked By Walk-Out". Seattle Daily Times. November 16, 1935. p. 1.

- 1 2 "400 Marooned By Ferry Strike". Seattle Daily Times. November 15, 1935. p. 1.

- ↑ "Kitsap Line Ordered To Resume Run To Vashon". Seattle Daily Times. November 14, 1935.

- ↑ "Victoria Ferry From Edmonds To Start Tomorrow". Seattle Daily Times. June 15, 1928.

- ↑ "Charter Holders Expecting To Buy City Of Victoria".

- ↑ "City Of Victoria Is Chartered To Ferry Company". Seattle Daily Times. May 12, 1929.

- ↑ "Ferry Withdrawn". Seattle Daily Times. September 3, 1930.

- ↑ "Summer Trips On Lake". Seattle Daily Times. June 12, 1924.

- ↑ "Most Unique Trip In America". Seattle Daily Times. July 8, 1926.

- ↑ Merchant Vessels Of The United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1935. p. 163.

- ↑ "From The Crow's Nest". Seattle Daily Times. June 16, 1935.

- ↑ "Ferries Given Back". Seattle Daily Times. November 22, 1937.

- ↑ "Interesting Travel Spots". Seattle Daily Times. June 27, 1935.

- ↑ "Mercer Island Tours Renewed". Seattle Daily Times. June 7, 1939.

- ↑ Merchant Vessels Of The United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1939. p. 434.

- ↑ "Sightseer Cruises Halted For Duration". Seattle Daily Times. June 10, 1942.

- ↑ "Saltwater People Log: ❖ The Sweet SIGHTSEER ❖". Saltwater People Log. Saltwater People Historical Society. 2014-03-05. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "See Seattle". Seattle Daily Times. June 23, 1946.

- 1 2 "Captain Anderson, Pioneer Lake-Ferry Operator, Dies". Seattle Daily Times. May 19, 1941.

- ↑ "Capt. Anderson's Estate Valued At $92,316". Seattle Daily Times. September 16, 1941.

- ↑ "Anderson - Matson". Daily Intelligencer. November 3, 1895.

- ↑ "Mrs. Emilie Anderson". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. January 27, 1959.

- ↑ "Three Tug Boats Are Sold". Seattle Daily Times. March 23, 1907.

- ↑ "Bills Of Sale". Seattle Daily Times. April 7, 1907.

- ↑ "Towboat Buckeye Enters Lake Trade". Seattle Daily Times. June 14, 1920.

- ↑ "Johan Adolph Anderson". www.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ↑ "Death Claims Capt. Anderson". Seattle Daily Times. January 5, 1936.

- 1 2 "Thirteenth Census Of The United States". www.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2020-03-27.

- ↑ "Albert Severin Anderson". www.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ↑ "Mattson". Seattle Daily Times. March 22, 1948.

- ↑ "Building Permits". Seattle Daily Times. June 1, 1928.

- ↑ "Fifteenth Census Of The United States". www.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2020-03-27.