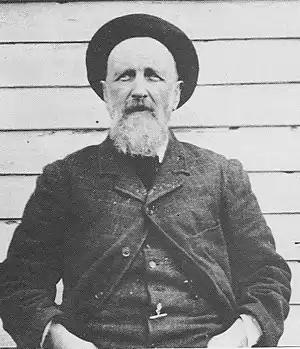

John La Gerche was a pioneering forester on the Victorian goldfields at Creswick, Australia in the late 19th-century.

Early life

John La Gerche was born on 22 May 1845 on the island of Jersey as the only son of Jean La Gerche and Marguerite La Mottee. His surname is a remnant of the island's Norman heritage, and he would have spoken fluent French as well as English. The La Gerche family were not only prominent farmers on the island, but his father was the local constable and lieutenant of the local militia.[1]

John grew up on a 14-acre farm which had been owned by the family since 1670. Between 1857 and 1862 he attended Victoria College for boys and excelled at his studies, winning prizes for proficiency in languages, (English, French and German), as well as mathematics.[2]

He emigrated to Victoria on the Agra from London as an “unassisted cabin passenger”, and arrived in Hobsons Bay near Melbourne on 30 March 1865. He listed his occupation on the manifest as "gentleman", and it is likely he had come to take up land as a new settler rather than as a gold miner.[1]

Elizabeth Nora Bendixon, also of Jersey, immigrated to Australia with her widowed mother and four sisters in 1859, and she worked as a housemaid to a wealthy family at Gisborne. It is uncertain where they met, but John La Gerche and Elizabeth married at Geelong on 17 July 1871.[1]

The Victorian Gold Rush – Impact on the forests

Before European settlement in the early 1800s, around 88% of the 23.7-million-hectare colony of what was to become the State of Victoria in 1851 was tree covered.[3]

However, the Victorian gold rush of the 1850s combined with widespread and indiscriminate land clearing for mining, agriculture and settlement became one of the major causes of forest loss and degradation.[4] Over the next three decades, the forests were denuded in the wasteful scramble to produce timbers for mining operations, such as poppet legs, props, laths, sawn timber and firewood for boilers. The forests were being rapidly and recklessly cleared in ever-widening circles around the goldfields.[4] By 1873 it was estimated that were some 1150 steam engines in the gold mining industry, devouring over one million tons of firewood.[5]

Forest management, government regulation and enforcement during this period was chaotic.[6] Ironically it was the timber needs of the mining industry, on which much of the colony's wealth was founded, that led the Government to finally act and set aside forest reservess. So in 1862, the assistant commissioner of Crown Lands, Clement Hodgkinson, withheld some 35,000 acres near the goldfields. The forests around Creswick were reserved later in 1866.[5]

At the urging of the Governor of Victoria, Lord Henry Brougham Loch, who had served in Bengal cavalry and maintained an interest in forests, the Government invited Conservator Frederick D'A. Vincent from the Imperial Forest Service in India to visit in 1887 and make recommendations. But to seek advice was one thing; to take it was another, and Vincent's scathing report was never tabled in Parliament.[5]

It was not until 14 June 1888, that the first conservator of forests for Victoria, George Samuel Perrin, was appointed. He had previous experience in South Australia and Tasmania and despite having little power or authority, was able to appoint a number of foresters over the next 12 years.[5]

Sawmilling enterprise

Meanwhile, in 1870 John La Gerche and his partner Dodd were operating a small sawmill in the Bullarook Forest (now known as Wombat Forest) between Leonards Hill and Daylesford. But it fell into financial difficulties and closed in 1875. Fierce competition from neighbouring sawmills like James Wheeler who had powerful political connections claimed an area of 640 acres where La Gerche and Dodd had been operating and a shortage of trees was partially to blame.[2] They took their grievances to Clement Hodgkinson but he didn't intervene and sent them home to reach a gentleman's agreement.

The absence of clear forest policies and regulations generally encouraged a sawmillers free-for-all. No doubt this had an effect on La Gerches' long term attitude to the ineffectiveness of government controls. In 1871, Hodkinson introduced local Forest Boards in a vain attempt to exercise control, but the task of regulating wasteful clearing proved formidable. The board employed only three bailiffs for the entire Wombat, Creswick- Ballarat districts: an impossible task on horseback. The Forest Boards were abolished in 1876.[5]

Meanwhile, timber licenses had been issued to sawmillers over 1000-acre blocks of the Wombat forest in 1873 but they allowed unlimited cutting and encouraged wastage. By 1897 the entire Wombat state forest was officially declared a "ruined forest".[1]

It is not clear what La Gerche subsequently did for the next six years after the collapse of his sawmilling enterprise.[1]

Crown Land Bailiff and Forester

Aged thirty-six and with a growing family La Gerche chose a more secure job in 1881 with the Public Works Department as a timekeeper. Later in October 1882, he was appointed as one of sixteen Crown Lands Bailiffs and Foresters within the Agriculture Branch of the Department of Lands. Their appointment held out a promise to end the forest destruction under the 1884 Land Act which recognised the significance of forests for public purposes but the budget allocation was a paltry £4000. His particular assignment was to supervise the Ballarat and Creswick State Forest, an area almost the third the size of his native Jersey and his principal focus was to enforce regulations against illegal cutting of timber. No doubt a thankless task.[1] His predecessor had been W. Llewelyn Jones.[5]

The distinction between Foresters and Bailiffs was one of both uniforms and jurisdiction. Bailiffs wore broad-brimmed hats and their authority extended over both Crown Lands and State Forests, whereas Foresters wore a smaller cap (La Gerche wore a beret) and were responsible for activities only upon State Forest. Only Bailiffs were able to prosecute matters in court but La Gerche held dual roles.[1]

However, as Bailiff, La Gerche had to work with poorly framed regulations. The licensing system was permissive and the courts and magistrates were more often sympathetic to the mining industry and woodcutters. He was also pitted against expert lawyers aiming to dismiss forest offences. Convictions proved hard to achieve unless he had personally observed the illegal cutting.[1]

It's reported that La Gerche rode the boundaries of the forest on his horse alone and often stayed overnight to guard the site. He could then hear the sound of the axes and follow the trails of the buggies illegally removing produce in the early morning mist. But the most successful and notorious timber cutters simply avoided him which wasn't hard to do so in the undulating forest. His diligence was not always supported by his distant superiors, and not surprisingly his tactics made him locally unpopular.[1]

But it is also reported that La Gerche resisted pressure to clear out the Chinese from the forest.[1]

Reforestation and repair

Part of John La Gerche responsibilities required him to grow and nurture a new crop of trees and to restore the landscape scared by mining but he complained he couldn't achieve that until he controlled illegal cutting.[7] However, Vincent's withering report in 1887 proved a watershed moment and John La Gerche's responsibilities shifted more to managing forests and plantations and less towards enforcement as a bailiff.[1]

Correspondingly, in 1887 La Gerche recommended that forest reserves should be closed until the trees had attained a diameter of 12 inches. During that time special licenses could be given for the purposes of cutting the scrub and crooked timber, leaving the straight saplings.[7] Without any formal forestry training or guidance, La Gerche initiated a pioneering thinning experiment on 100 acres of Creswick forest to remove scrub and crooked trees but retain the healthy straight saplings. Messmate, Eucalyptus obliqua, was the preferred species compared to less valuable peppermints and it responded well to the treatment.

John La Gerche was able to accompany Frederick D'A. Vincent during his visit to the Creswick forest in June 1887 and Vincent was later complimentary of his work to restore the forest landscape.[1]

He began the immense task of restocking of the forest modestly in 1883 by experimenting with one pound of blue gums seeds. The seedlings were not successful, but he was not easily discouraged.[1] John La Gerche undertook more trials of establishing Eucalyptus globulus and raised Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus cladocalyx seedlings in the nursery in the late 1890s.

Sawpit Gully Nursery

Not long after commencing his new role, La Gerche began repairing the denuded Creswick forest. Earlier in 1872, a government nursery had been established at Macedon by Victoria's first “Overseer of Forests and Crown Land Bailiff", William Ferguson. La Gerche worked closely with Macedon to obtain seedlings and advice.[5]

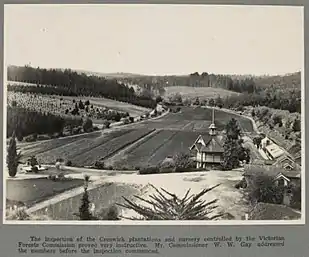

In 1887, John La Gerche established a small plantation in Sawpit Gully north of Creswick by enclosing a 2-acre plot and transplanting over 700 seedlings. La Gerche chose the Sawpit Gully site because he was advised that its slopes and soils were “the very thing for growing pines”. The location was highly disturbed by old gold diggings, but it had a water race snaking around the spurs.[7] He established a nursery in 1888. The owner, Albert Wade, prepared the land for planting and agreed to become caretaker.

By 1889 La Gerche had planted over 19,000 trees in the plantation areas near the nursery. Aided by Albert Wade, a retired miner, the enormous task of fencing, digging holes and planting seedlings had the adjoining plantation reaching its largest size ten year later in 1899, covering 300 acres with 24,000 trees. But the Creswick climate proved harsh on the first plantings, with low rainfall and some characteristic severe frosts.[8]

In 1889 about 100,000 seedlings raised at sawpit gully nursery we moved to the abandoned New Australia Mine site just north of Creswick.

The forester in charge of the Ballarat Water Commission, Christopher Mudd, also supported La Gerche by exchanging seeds, plants and ideas.[1] From 1888 the Conservator of Forests, George Perrin also took a special interest in the nursery and plantation.[5] La Gerche was resourceful and obtained new trees and seedlings from any sources he could find, including some trees from the Ballarat botanical gardens.[8] With the encouragement of Perrin new species were introduced to include planes, oaks, English maples, limes, several species of pines, sycamore, elms and poplar.

Meanwhile, and perhaps exemplifying the influence of Indian forestry throughout the British Empire, the State Government invited Inspector-General Berthold Ribbentrop, also from the Imperial Forest Service in 1895 to inspect and report on Victoria's forests.[9] He underscored "State forest conservancy and management are in an extraordinary backward state". Ribbentrop's report prompted yet another Royal Commission which commenced in 1897 and produced 14 separate reports before closing in 1901.

By 1897, the year of his departure from Creswick, nearly three-quarters of the forest had been thinned, much of it fenced and many plantations established. Mining was in decline and pilfering had practically ceased. The number of cattle in the forest had greatly diminished and their owners departed. While La Gerche had personally planted over 100,000 seedlings.[1]

Departmental restructuring is not new. Between 1856 and 1907 the responsibility for administration of Victoria's forest estate shunted back and forth at least eleven times between three Government Departments including Lands and Survey, Agriculture and Mines.[10][11] The State Forest Department was finally created in 1908 and La Gerche was appointed one of its founding Inspectors along with W J Code, and J Firth.[5] The State Forests Department later became the Forests Commission Victoria in December 1918.

Later in 1908, La Gerche's original nursery was moved back to its present site further down the gully to coincide with the opening of the Victorian School of Forestry.

Legacy

John La Gerche died on 18 November 1914 and was buried in the Ballaarat old Cemetery with his wife Nora.

La Gerche was largely forgotten until the 1960s when his detailed pocket books turned up at the Victorian School of Forestry (VSF) at Creswick and then later in the 1980s his letters were found in a dusty cupboard in the old forest office at Melbourne.[7]

A bushfire swept through much of the Creswick forest in February 1977 and destroyed many of the stands of trees he planted but it is possible to still to find some remnants.

In 1998, the La Gerche Trail was opened to commemorate his life and works. The walking trail was established by a senior lecturer from the nearby Forestry School, Ron Hateley, and students of the University of Melbourne, in collaboration with Victorian Landcare Centre which was based at the old nursery at that time. It is now managed by Parks Victoria.

A commemorative statue of John La Gerche can be found on the trail which was carved by the Creswick Railway Workshops Association in 2014 from a fallen 112-year old Sequoia sempervirens (Californian Redwood), believed to have been planted in 1902 by La Gerche's successor, John Johnson who was then the Superintendent of State Plantations.[12][13]

The Sawpit Gully area, including the nursery site and plantation, was granted heritage status in 2015.[1][8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Taylor, Angela (1998). A Foresters Log. Melb University Press. ISBN 0522848397.

- 1 2 "John La Gerche".

- ↑ Victoria State of the Forests Report (2013). Dept of Env and Primary Industries.ISBN 978-1-74326-575-8

- 1 2 Carron, L T (1985). A History of Forestry in Australia. Aust National University. ISBN 0080298745.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Moulds, F. R. (1991). The Dynamic Forest – A History of Forestry and Forest Industries in Victoria. Lynedoch Publications. Richmond, Australia. pp. 232pp. ISBN 0646062654.

- ↑ Legg, S M (2016). "Political Agitation for Forest Conservation: Victoria, 1860–1960". International Review of Environmental History. 2: 28. doi:10.22459/IREH.02.2016.01.

- 1 2 3 4 Rob Youl, Brian Fry and Ron Hately (eds), Circumspice: One Hundred Year of Forestry Education Centred on Creswick, Victoria, South Melbourne: Forest Education Centenary Committee, 2010

- 1 2 3 Victorian Heritage Database Report

- ↑ "Report on the state forests of Victoria : prepared in compliance with the request of the Hon. R. W. Best, Minister of Lands" (PDF). 1896.

- ↑ "Forest Commission Victoria". National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Gillespie J & Wright J (1993). A Fraternity of Foresters. A history of the Victorian State Foresters Association. Jim Crowe Press. pp. 149 pp. ISBN 0646169289.

- ↑ "John La Gerche Monument".

- ↑ "La Gerche - 100 Project".

External links

- McHugh, Peter. (2020). Forests and Bushfire History of Victoria : A compilation of short stories, Victoria. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2899074696/view

- FCRPA - Forests Commission Retired Personnel Association (Peter McHugh) - https://www.victoriasforestryheritage.org.au

- https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/cchc/