John Outterbridge | |

|---|---|

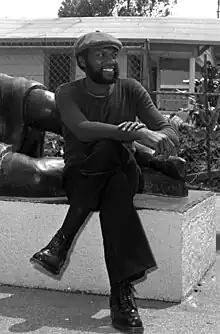

Outterbridge in 1977 | |

| Born | March 12, 1933 Greenville, North Carolina |

| Died | November 12, 2020 Los Angeles, California |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Agricultural and Technical University in Greensboro, North Carolina; Chicago Academy of Art; American Academy of Art |

John Outterbridge (March 12, 1933 – November 12, 2020) was an American artist and community activist who lived and worked in Los Angeles, California. His work explores the issues surrounding personal identity such as family, community and the environment through the use of discarded materials.[1]

He was the first director of the Watts Towers Art Center, and served in that role for seventeen years. His sculptural work has been reviewed in The New York Times,[2] and his work is owned by many prominent museums.[3]

Personal life

John Wilfred Outterbridge was born and grew up in Greenville, North Carolina. His father made a living by recycling metal machine parts and equipment, and Outterbridge was exposed to recycling materials as a result.[4]

His college education began at the Agricultural and Technical University in Greensboro, North Carolina, where he studied to become a mechanical engineer. A year later, Outterbridge joined the military, where his interests in art developed seriously. Once he finished serving in 1956, he enrolled in the Chicago Academy of Art and later the American Academy of Art.[5]

In the 1960s Outterbridge married and moved to Los Angeles. He became a highly respected community activist, educator and director of the Watts Towers Arts Center from 1975 to 1992.[6][5]

In 1991, Outterbridge retired and pursued a greater focus on art.

Outterbridge died on November 12, 2020, in Los Angeles of natural causes at the age of 87.[7]

Artistic career

During a tour of duty in Europe, Outterbridge visited museums and painted street scenes from life in his spare time. His paintings were well liked, and he painted murals and artwork for offices, clubs and American schools.[4]

Once he moved to L.A., Outterbridge began to combine painting with the collection of objects. His first real forays into assemblage were a series of car sculptures made of stainless steel from a junkyard. He believed the materials society used said a lot about the attitudes and history of people.[5]

Some of his earliest and widely known works were made during the Watts Riots. From 1963 to 1971, rioting and civil unrest struck the nation's black communities, resulting in the signing of the Civil Rights bill. It was a sign that race relations were a real problem in the USA that needed to be addressed.[8] Outterbridge collected the debris that covered the streets from this historic event to create sculptures. The final work was deeply steeped in politics and resulted in Outterbridge continuing to confront these themes in his work. Through this, Outterbridge befriended artists who were interested in the same subject matter— such as David Hammons, Timothy Washington, and John T. Riddle Jr.—and revived the California Assemblage Movement, where he would become a prominent figure.[9][10]

The Containment Series (1968) was another one of Outterbridge's forays into assemblage. It grew out of an interest in containment and a desire to disrupt the societal and institutional norms that reinforced it. To do so, he destroyed the canvas and covered it with items like aluminum panels, bolts, leather belts and paint. Outterbridge also relied on the muted natural colors of the object he found and reserves louder colors for focal points.[8]

Recent work recounts some of the ideas Outterbridge investigated in earlier sculptures. In Dreads (2011), he assembled a mallet and his own clipped dreadlocks. The handle of the mallet was phallic and according to Outterbridge alluded to the concept of passion.[8]

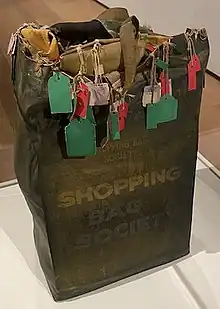

Outterbridge incorporated history in many of his pieces. Case in Point, from the Rag-Man series, is a piece of luggage reminiscent of dynamite and is symbolic of the Great Migration. Attached to the cylindrical forms is a baggage tag that says, "packages travel like people".[11] Case in Point confronts the racist reality of African Americans at home after serving the country in the Korean War.

Although Outterbridge lived a relatively successful life, his pursuits into education and community activism did take a toll on his artistic career.[1] Coupled with the quiet segregation of the art world up till the 21st century, Outterbridge did not receive much acclaim from his work outside of the West Coast until 1994.[8][12] He represented the United States at the São Paulo Biennale in a show called The Art of Betye Saar and John Outterbridge: The Poetics of Politics, Iconography and Spirituality. Nearly 20 years after he began practicing as a professional artist, a new generation came to appreciate his vast body of work.[8]

Outterbridge appeared in many group and solo exhibitions, such as The Rag Factory (2011) at LAXART, his first solo exhibition since 1966. The Rag Factory was an installation using rags that Outterbridge collected from the streets and factories of downtown Los Angeles, by tying, draping, folding, gathering and suspending them.[12]

Awards

In 2012, the California African American Museum gave their lifetime achievement award to Outterbridge.[13] He was named a United States Artists Gracie Fellow for Visual Arts in 2011.[14] In 1994, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Otis College of Art and Design.[15] In addition to these, Outterbridge received fellowships from the Fulbright Foundation, Getty Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.[4]

References

- 1 2 Choi, Connie H. (2016). "John Outterbridge". Hammer Museum.

- ↑ Glueck, Grace (January 31, 1997). "Art in Review". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ↑ Kim, Nic Cha (January 18, 2021). "Assemblage Artist John Outterbridge Leaves Behind Legacy of Arts Education". Spectrum News. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Ueno, Rihoko (October 7, 2016). "A Finding Aid to the John Outterbridge Papers, 1953–1997,in the Archives of American Art" (PDF). aaa.si.edu. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Isenberg, Barbara S. (2005). State of the Arts: California Artists Talk About Their Work. Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1-56663-631-0. OCLC 57341997.

- ↑ Vankin, Deborah (October 11, 2021). "A Watts Towers mural faded in plain sight. Three generations of artists bring back its zing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ↑ Finkel, Jori (January 1, 2021). "John Outterbridge, Who Turned Castoffs Into Sculpture, Dies at 87". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Weaver, A.M. (2013). "Reflections on John Outterbridge". Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art. 2014 (35): 32–41. doi:10.1215/10757163-2827976. S2CID 191590946.

- ↑ Neuendorf, Henri (August 5, 2016). "Why Artist John Outterbridge Is Key to the LA Art Scene". artnet.com.

- ↑ Ahn, Abe (August 6, 2019). "The LA Artists Who Advanced Black Stories Through Art-Making". Hyperallergic. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ↑ Travers, Andrew (October 6, 2016). "Rag Man's Last Stand". Aspen Times Weekly.

- 1 2 Buckley, Annie (January 20, 2012). "John Outterbridge". Art in America. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ↑ Ng, David (August 16, 2012). "Sidney Poitier, John Outterbridge to receive honors". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ↑ United States Artists official website. ,

- ↑ "Otis College of Art and Design – Commencement Speakers and/or Honorary Degrees Starting in 1962" (PDF). Otis College of Art and Design. Retrieved May 12, 2017.