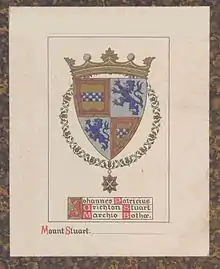

The Marquess of Bute | |

|---|---|

| |

| Known for | Philanthropy |

| Born | 12 September 1847 Mount Stuart, Scotland, United Kingdom |

| Died | 9 October 1900 (aged 53) |

| Buried | Isle of Bute; Mount of Olives, Jerusalem |

| Residence | Mount Stuart House (main residence) Cardiff Castle Chiswick House Dumfries House House of Falkland St John's Lodge |

| Spouse(s) | Gwendolen Fitzalan-Howard |

| Issue | John, 4th Marquess Lord Ninian Lord Colum Lady Margaret |

| Parents | John, 2nd Marquess Lady Sophia Rawdon-Hastings |

John Patrick Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute, KT (12 September 1847 – 9 October 1900) was a Scottish landed aristocrat, industrial magnate, antiquarian, scholar, philanthropist, and architectural patron.

When Bute succeeded to the marquisate at the age of just six months, his vast inheritance reportedly made him the richest man in the world. He owned 116,000 acres mostly in Glamorgan, Ayrshire and Bute.[1] His conversion to Catholicism from the Church of Scotland at the age of 21 scandalised Victorian society and led Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli to use the Marquess as the basis for the eponymous hero of his novel Lothair, published in 1870. Marrying into one of Britain's most illustrious Catholic families, that of the Duke of Norfolk, Bute became one of the leaders of the British Catholic community. His expenditure on building and restoration made him the foremost architectural patron of the 19th century.

Lord Bute died in 1900, at the age of 53; his heart was buried on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. He was a Knight Grand Cross of the Holy Sepulchre, Knight of the Order of St. Gregory the Great and Hereditary Keeper of Rothesay Castle.[2]

Early life

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The future Marquess was born at the family seat of Mount Stuart, on the Isle of Bute in Scotland, to John, 2nd Marquess of Bute, and Lady Sophia Rawdon-Hastings, daughter of The 1st Marquess of Hastings.[3] At birth, he was known by the courtesy title Earl of Dumfries.

The 2nd Marquess was an industrialist and began, at great financial risk, the development of Cardiff as a port to export the mineral wealth of the South Wales Valleys. Accumulating major debts and mortgages on his estates, the Marquess rightly foresaw the potential of Cardiff, telling his concerned solicitor in 1844, "I am willing to think well of my income in the distance." The following fifty years saw his faith vindicated, but the ensuing riches were to be enjoyed, and spent, by his son, "the richest man in the world",[4] rather than himself.

The 2nd Marquess died in 1848 and his son succeeded to the Marquessate when less than six months old. He was educated at Harrow School, and matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford in 1865.[5][6] His mother died when he was 12. Bute had been attracted to the Roman Catholic Church since childhood, and the efforts of his guardians to weaken this attraction only added to it. He was never a member of the Church of England, despite efforts by Henry Parry Liddon to attract him to it.[7] Bute's letters to one of his very few intimate friends during his Oxford career show with what conscientious care he worked out the religious question for himself. On 8 December 1868, he was received into the Church by Monsignor Capel at a convent in Southwark, and a little later was confirmed by Pius IX in Rome, resulting in a public scandal. His conversion was the inspiration for Benjamin Disraeli's novel, Lothair.[8]

Interests

The Marquess's vast range of interests, which included religion, medievalism, the occult, architecture, travelling, linguistics, and philanthropy, filled his relatively short life. A prolific writer, bibliophile and traveller, as well as, somewhat reluctantly, a businessman, his energies were on a monumentally Victorian scale. "A liturgist and ecclesiologist of real distinction",[9] he published on a wide range of topics. But at a distance, just over one hundred years from his death, it is his architectural patronage as "the greatest builder of country houses in nineteenth-century Britain"[10] that creates his lasting memorial.

In 1865, the Marquess met William Burges and the two embarked on an architectural partnership, the results of which long outlasted Burges' own death in 1881. Bute's desires and money allied with Burges' fantastical imagination and skill led to the creation of two of the finest examples of the late Victorian era Gothic Revival, Cardiff Castle[11] and Castell Coch.[12] The two buildings represent both the potential of colossal industrial wealth and the desire to escape the scene of that wealth's creation. The theme recurs again and again in the huge outpouring of Bute's patronage, in chapels, castle, abbeys, universities and palaces. Bute's later buildings are hardly less remarkable than his collaborations with Burges. Robert Rowand Anderson rebuilt the Georgian Mount Stuart House for him, and Bute worked in collaboration with many of Burges's colleagues, including William Frame and Horatio Walter Lonsdale, on the interiors. John Kinross was Bute's architect for the sympathetic and creative reworking of the partially ruined Falkland Palace. Kinross also restored Greyfriars in Elgin for Bute.[7]

As a burgess of Cardiff, the Marquess accepted the invitation to be mayor of Cardiff for the municipal year from November 1890.[13]

Patronage

The Marquess's patronage was extensive, with a particular enthusiasm for buildings of religion and academia. Whilst Rector of the University of St Andrews, he provided the university with a new home for its Medical School and endowed the Bute Chair of Medicine. A supporter of education for women, he also paid for St Andrews University's first female lecturer, who taught anatomy to women medical students when Professor James Bell Pettigrew refused to do so.[7] At the University of Glasgow, he gifted the funds required to complete the university's huge central hall, named the Bute Hall in his honour, and he is commemorated both at the university's Commemoration Day and on its Memorial Gates. He was made the Honorary President (Scottish Gaelic: Ceannard Urramach a' Chomainn) of the Highland Society of the University of Edinburgh.

Between 1868 and 1886 he financed the rebuilding of St Margaret's Parish Church, Roath, Cardiff, creating a new mausoleum for the Bute family with sarcophagi in red marble.[14]

In 1866 he donated a site in Cardiff Docks for the Hamadryad Hospital Ship for sick seafarers and, on his death in 1900, bequeathed £20,000 towards the cost of a new bricks-and-mortar hospital, which became the Royal Hamadryad.[15]

The Marquess of Bute's Case

The Marquess was involved in a notable company law case, known as "the Marquess of Bute's Case", reported on appeal in 1892, called Re Cardiff Savings Bank [1892] 2 Ch 100. The Marquess had been appointed to the board of directors of the Cardiff Savings Bank as "President", at the age of six months, in effect inheriting the office from his father. He attended only one board meeting in the next 38 years. When the bank became insolvent following a fellow director's fraudulent dealing, Stirling J held that the Marquess was not liable as he knew nothing of what was going on. It was not suggested that he ought to have known what was going on or that he had a duty of care to inform himself as to the affairs of the bank. The case set a famous legal precedent, now superseded, for the minimal view of the duties of company directors. It was naturally a considerable embarrassment for the Marquess although he escaped legal blame.

Family life

John, 3rd Marquess of Bute, married Gwendolen Fitzalan-Howard (daughter of The 1st Baron Howard of Glossop and granddaughter of The 13th Duke of Norfolk) in 1872 and had four children:

- Lady Margaret Crichton-Stuart (24 December 1875 – 6 June 1954)

- John, 4th Marquess of Bute (20 June 1881 – 16 May 1947)

- Lord Ninian Edward Crichton-Stuart (15 May 1883 – 2 October 1915)

- Lord Colum Edmund Crichton-Stuart (3 April 1886 – 18 August 1957)

Works

- John, Marquess of Bute (1911). Brendan's Fabulous Voyage. via Project Gutenberg

- The Roman breviary. Translated by John, Marquess of Bute (New Rev ed.). Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. 1908. via The Internet Archive

Death

Lord Bute died on 9 October 1900[5] after a protracted illness (Bright's disease), his first stroke having occurred in 1896,[7] and was buried in a small chapel on the Isle of Bute, his ancestral home. His heart was buried on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.

In his will he left £100,000 to each of his children, with the exception of his eldest son, who inherited the Bute estates including Cardiff Castle and the family seat, Mount Stuart House on the Isle of Bute, and Dumfries House in Ayrshire.[15]

Notes

- ↑ The great landowners of Great Britain and Ireland

- ↑ Converts to Rome by Gordon Gorman 1885

- ↑ Hannah 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ Crook 2013, p. 231.

- 1 2 Llewelyn Davies, Sir William (1959). "Bute, marquesses of Bute, Cardiff Castle, etc.". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ↑ Foster, Joseph (1888–1892). . Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715–1886. Oxford: Parker and Co – via Wikisource.

- 1 2 3 4 Hannah 2012, p. ?.

- ↑ Davies 1981, p. 26.

- ↑ Cannadine 1992, p. 489.

- ↑ Hall 2009, p. 91.

- ↑ Girouard 1979, pp. 273–290.

- ↑ Girouard 1979, pp. 336–345.

- ↑ ""Lord" Mayor of Cardiff". The Cardiff Times. 25 October 1890. p. 6 – via Welsh Newspapers Online.

- ↑ Lynn F. Pearson, Mausoleums, Shire Publications Ltd. (2002), page 39. ISBN 0 7478 0518 0

- 1 2 "Lord Bute's Will - Bequest to the Seaman's Hospital - Explanation of the Conditions". Western Mail. 19 October 1900. p. 5. Retrieved 10 December 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

References

- Cannadine, David (1992). The Decline & Fall of the British Aristocracy. London, UK: Pan. ISBN 0-330-32188-9.

- Crook, J. Mordaunt (2013). William Burges and the High Victorian Dream. London, UK: Francis Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-3349-2.

- Davies, John (1981). Cardiff and the Marquesses of Bute. Cardiff, UK: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-2463-9.

- Girouard, Mark (1979). The Victorian Country House. New Haven, US: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02390-9.

The Victorian Country House.

- Hall, Michael (2009). The Victorian Country House: From The Archives of Country Life. London: Aurum Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84513-457-0.

- Hannah, Rosemary (2012). The Grand Designer: Third Marquess of Bute. Edinburgh, UK: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-78027-027-2.

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Marquess of Bute

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Works by John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute at Internet Archive

- K. D. Reynolds. "Stuart, John Patrick Crichton-, third marquess of Bute (1847–1900)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26722. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)