.jpg.webp)

John Yapp Culyer (May 18, 1839 – 1924) was an American civil engineer, landscape architect, and architect, who worked on parks in Chicago, Pittsburgh and other cities. He is known as the Chief Landscape Engineer of Prospect Park opened in 1867.

Biography

Born in New York city, May 18, 1839 ; son of John and Sarah (Norton) Culyer. He was educated in private schools and studied surveying and engineering under Professor Richard H. Bull of the University of the city of New York.[1]

He then spent one year in an architect's office in New York city. He was a member of the engineer corps under Frederick Law Olmsted, superintendent of Central Park, New York city, where he developed a talent for landscape architecture, especially in road construction, surface treatment and planting. In 1861 he accompanied Mr. Olmsted to Washington, D.C., where he assisted in organizing the U.S. Sanitary Commission. He then entered the engineer corps, U.S. army, under General George Dashiell Bayard, and was engaged on fortification and defence works in Virginia south of the Potomac river.[1] On April 14, 1865, Culyer witnessed the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.[2]

At the close of the war he was made engineer on Central Park by Comptroller A. H. Green, and in 1866 he assisted Mr. Stranahan in organizing and Mr. Olmsted in laying out Prospect Park, Brooklyn, N.Y., where he was employed for twenty years on the public parks, boulevards and parkways. He resigned in 1886 and engaged as an expert landscape architect and was employed on parks in Chicago, New Orleans, Nashville, New York, Brooklyn, Albany, Pittsburg and Paterson. He attained the rank of lieutenant -colonel and engineer in the N.Y. state national guard; was active in developing rapid transit in Brooklyn ; and was a member of the board of education for twenty-five years.[1]

He was elected secretary and advisory landscape architect of the Tree Planting association of New York city and contributed articles on landscape gardening, sanitary reforms and educational advancement to the leading journals of America.[1]

Work

Early organizational chart, 1864

In 1861 Culyer accompanied Frederick Law Olmsted to Washington, D.C., where he assisted in organizing the U.S. Sanitary Commission. One of the things they accomplished was the design of a modern organizational chart of the U.S. Sanitary Commission in 1864, entitled "Diagram illustrating the working organization of the United States Sanitary Commission." In the upper right corner they described, how to read the chart and which colour coding was used. It reads:

The Circles represent not individual workers but departments or subdivisions of labor.

The lines represent lines of responsibility. Each center from which lines diverge is responsible for the right management of the several departments radiating from it.

What is distinctly Medical is represented by Green: what is distinctly Special Relief is represented by red. All other departments are represented by Black."

This chart is one of the first modern organizational charts, but it was not the first in its kind. Two years earlier in 1862 the Attorney and Counselor N. Medal Shafer had drawn a Diagram of the Federal Government and American Union. And ten years before in 1854 the Scottish-American engineer Daniel McCallum (1815–1878) created the first organizational chart of American business[3] around 1854.[4][5] This chart was drawn by George Holt Henshaw.[6]

The Sanitary Commission Bulletin of Feb. 1, 1864 reported, that this chart was used in an early 1864 meeting to explain the work of commission to its participants.[7] In the same year the foreign agent of the United States sanitary commission Charles SP. Bowles reported, that initially multiple large engraved diagrams, showing its working organization, existed.[8]

Flatbush Town Hall, 1874-75

Flatbush Town Hall at 35 Snyder Avenue between Flatbush and Bedford Avenues in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York City, was built in 1874-75 and was designed by Culyer in the High Victorian Gothic style in the Ruskinian mode.

It dates from the time before the Town of Flatbush was integrated into the City of Brooklyn, in 1894. Afterwards the building served as a magistrate's court and the New York City Police Department's 67th Police Precinct station.[9]

In the late 1980s the building underwent a renovation and refurbishment, and it is now used as a community center.[10][11]

Eastside Park, Paterson, 1888

Eastside Park, Paterson was designed by Cuyler in cooperation with Fred Wesley Wentworth, and Welch, Smith & Provot, build in 1888. The Eastside Park Historic District is a residential neighborhood in the Eastside of Paterson, New Jersey east of downtown. Once the home of the city's industrial and political leaders, the neighborhood experienced a significant downturn as industry fled Paterson, but has since seen a revival in interest in the mansions and large homes in the area.

Flatbush District No. 1 School, 1894

The Flatbush District No. 1 School at 2274 Church Avenue on the corner of Bedford Avenue in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York City, was built in 1878 on land that was formerly the Flatbush African Burial Ground and was designed by Culyer in the Rundbogenstil style, with a southern addition which dates from 1890 to 1894.

The school, which dates from the period before the Town of Flatbush was integrated into the City of Brooklyn in 1894, was later designated Public School 90, but the building was closed in 1951. Since then, it has been used as Yeshiva University's Boy's High School and the Beth Rivkah Institute, but is currently vacant.[12]

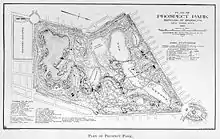

Prospect Park and other works

Culyer assisted in laying out Prospect Park, Brooklyn, N.Y., where he was employed for twenty years on the public parks, boulevards and parkways. The park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux after they completed Manhattan's Central Park. Attractions include the Long Meadow, a 90-acre (36 ha) meadow, the Picnic House, Litchfield Villa, Prospect Park Zoo, The Boathouse, housing a visitors center and the first urban Audubon Center;[13] Brooklyn's only lake, covering 60 acres (24 ha); the Prospect Park Bandshell that hosts free outdoor concerts in the summertime.

The Brooklyn Historical Society summarized, that "during the park's construction, Culyer was charged by the park's commission to oversee the development of the park's public uses. He also oversaw the construction of Ocean Parkway, the Concourse at Coney Island, and was involved in the construction of several railroads in Brooklyn."[14]

After his resignation in Brooklyn in 1886, Culyer was engaged as an expert landscape architect and was employed on parks in Chicago, New Orleans, Nashville, New York, Brooklyn, Albany, Pittsburg and Paterson.[1]

Publications

- John Yapp Culyer. An Address on Industrial and Inventive Drawing in Public Schools, Delivered Before the New York State Association of County Commissioners and City Superintendents of Common Schools, at the Albany High School, Thursday Evening, March 29, 1877, by Jno. Y. Culyer, of Brooklyn, N.Y. 1877.

- John Yapp Culyer. Engineering: Applicable to the National Guard, 1885.

- John Yapp Culyer, Edward Payson North, A. F. Noyes. Report of Examination and Tests of the Aveling & Porter and Harrisburg Steam Road-rollers: By a Commission of Civil Engineers, Consisting of J. Y. Culyer, E. P. North, A. F. Noyes, 1890.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brown, John Howard. "Culyer, John Yapp" in: Lamb's Biographical Dictionary of the United States. Vol 2. 1900. p.295-6.

- ↑ John Y. Culyer. "The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln,"in: The Magazine of History, with Notes and Queries, 1916. p. 58-60.

- ↑ Alfred D. Chandler Jr. (1962). Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- ↑ Burton S. Kaliski (2001). Encyclopedia of business and finance. p.669.

- ↑ For years people believed no copy of this chart survived, see for example: Sidney Pollard, Richard S. Tedlow (2002) Economic History. p. 18

- ↑ Caitlin Rosenthal (2012) "Big data in the age of the telegraph Archived 2015-05-09 at the Wayback Machine" in McKinsey Quarterly, March 2013.

- ↑ Sanitary Commission Bulletin of Feb. 1, 1864 in: United States Sanitary Commission Bulletin: Numbers 1 to 12, Vol. 1. (1866) p. 194

- ↑ Bowles, Charles SP. Report of Charles SP Bowles foreign agent of the United States sanitary commission. Gale Cengage Learning. 1864. p.

- ↑ T. Robins Brown (April 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Registration:Flatbush Town Hall". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ↑ Guide to NYC Landmarks (4th ed.)

- ↑ AIA Guide to NYC (5th ed.)

- ↑ Guide to NYC Landmarks (4th ed.)

- ↑ "Audubon New York". National Audubon Society. 2008. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ↑ John Yapp Culyer collection, 1921 – 1955. Accessed 13.01.2015.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Brown, John Howard. "Culyer, John Yapp" in: Lamb's Biographical Dictionary of the United States. Vol 2. 1900. p. 295-6.

This article incorporates public domain material from Brown, John Howard. "Culyer, John Yapp" in: Lamb's Biographical Dictionary of the United States. Vol 2. 1900. p. 295-6.

External links

Media related to John Y. Culyer at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to John Y. Culyer at Wikimedia Commons- John Yapp Culyer collection, 1921 – 1955