John of Würzburg (Latin Johannes Herbipolensis) was a German priest who made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the 1160s and wrote a book describing the Christian holy places, the Descriptio terrae sanctae (Description of the Holy Land).[2]

Life

All that is known of John's life is what he records in his Descriptio. He says that he was a priest of the church of Würzburg and he dedicated his work to a friend named Dietrich (Theoderic). The Tegernsee manuscript calls John the bishop of Würzburg, but there was no bishop named John. Possibly the copyist or whoever added the description of John to the Tegernsee manuscript confused him with his friend, who is sometimes identified with Dietrich of Hohenburg, who was bishop of Würzburg in 1223–24. This identification is not certain.[2] Nor is the identification of Dietrich with the man of the same name who went on a pilgrimage around 1172 and wrote his own account of it, the Libellus de locis sanctis.[3]

John's pilgrimage took place while the holy places belonged to the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem, but before the major renovation of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. He may have written his Descriptio several decades after the pilgrimage, possibly after 1200.[4] His account is not entirely based on what he himself saw, he admits that he made use of eyewitness reports and in some cases borrowed from other travel guides (especially Fretellus[5]). He probably landed at Acre, when he travelled to Nazareth, Jenin, Nablus, Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Jaffa, where he took ship home. His description of these places is mostly that of an eyewitness.[2]

Descriptio

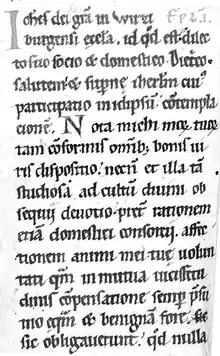

The Descriptio is known from four manuscripts. The earliest and longest, now Clm. 19418 in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich, dates to the late 12th or early 13th century and comes from Tegernsee Abbey.[5]

John's Latin is educated but ordinary.[2]

John's purpose in writing was to update the 7th-century description of the Holy Land, De locis sanctis, which he knew from the version edited by Bede, based on the construction projects that had taken place since the First Crusade.[5]

The text is structured around the life of Jesus and divided into seven sections highlighting his birth, baptism, passion, descent into Hell, resurrection, ascension and judgement. This structure was considered irrational by Titus Tobler, who rearranged the text for his edition.[5]

The Descriptio is the earliest western source to contain information about the different Christian denominations in the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[5][6] It has also aroused interest for its early indications of the rise of national feeling in Europe. John was a German patriot who laments the lack of credit given to the German crusaders.[3] In his thirteenth chapter, he writes:

Three days afterwards is the anniversary of noble Duke Godfrey [of Bouillon] of happy memory, the chief and leader of that holy expedition, who was born of a German family. His anniversary is solemnly observed by the city with plenteous giving of alms in the great church, according as he himself arranged while yet alive. But although he is there honoured in this way for himself, yet the taking of the city is not credited to him with his Germans, who bore no small share in the toils of that expedition, but is attributed to the French alone.[7]

See also

Editions

- Johannes von Würzburg (1874). "Descriptio terrae sanctae". In Titus Tobler (ed.). Descriptiones terrae sanctae. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs. pp. 108–192, 415–448.

- John of Würzburg (1890). Description of the Holy Land. Translated by Aubrey Stewart. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

References

- ↑ John of Würzburg 1890, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Stewart, "Preface" to John of Würzburg 1890, pp. ix–xii.

- 1 2 Alfred Wendehorst (1974), "Johannes von Würzburg", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 10, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, p. 577; (full text online).

- ↑ So the early modern historians Johann Albert Fabricius and Bernhard Pez believed.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Timothy S. Jones (2000), "John of Würzburg (fl. 1160)", in John Block Friedman; Kristen Mossier Figg (eds.), Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, pp. 309–310

- ↑ Jonathan Rubin, Learning in a Crusader City: Intellectual Activity and Intercultural Exchanges in Acre, 1191–1291 (Cambridge University Press, 2018), p. 140.

- ↑ John of Würzburg 1890, p. 40.