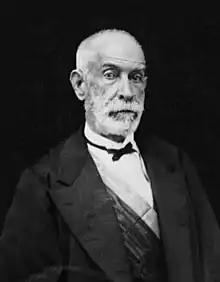

José María Linares | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Juan de la Cruz Tapia, 1860 | |

| 13th President of Bolivia | |

| In office 9 September 1857 – 14 January 1861 | |

| Preceded by | Jorge Córdova |

| Succeeded by | José María de Achá |

| Minister of the Interior and Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 16 November 1839 – 10 June 1841 | |

| President | José Miguel de Velasco |

| Preceded by | Manuel María Urcullu |

| Succeeded by | Manuel María Urcullu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | José María Linares Lizarazu July 10, 1808 Ticala, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (now Bolivia) |

| Died | 23 October 1861 (aged 53) Valparaíso, Chile |

| Spouse | María de las Nieves Frías Gramajo |

| Children | Josefa Sofía Linares Frías |

| Parents |

|

| Education | University of San Francisco Xavier |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | .svg.png.webp) |

José María Linares Lizarazu (10 July 1808 – 23 October 1861) was a Bolivian lawyer and politician who served as the 13th president of Bolivia from 1857 to 1861. Commencing his political career at a young age, he emerged as a fervent advocate of free trade, liberalism, the exploitation of silver mines, and the establishment of a monopoly on mercury to facilitate the latter objective.

Linares served as Minister of the Interior and Foreign Relations in the third cabinet of José Miguel de Velasco, but due to differences with the "Restoration" movement, he had to go into exile in Spain. In 1848, he returned to his country and became the President of the Congress. He defended President Velasco against Manuel Isidoro Belzu, and after Velasco's fall, he fled to Argentina and inspired various conspiracies against Belzu.

In 1857, he overthrew President Jorge Córdova, Belzu's son-in-law, and assumed the presidency. Linares, Bolivia's first civilian president, declared himself dictator in 1858 and confronted the power of the clergy and the military through a reform program. He repressed several uprising attempts, and in 1861, he was deposed by his own supporters and replaced by a triumvirate that sentenced him to exile. The former president fled to Chile, where he died shortly after his exile.

Early life

Family and education

He was born in Ticala, Potosí Department, in his family's hacienda. Belonging to the noble and wealthy family of the Counts of Casa Real and Lords of Rodrigo in Navarre, Linares was related to the Spanish nobility. He was educated at the Royal and Pontifical University of San Francisco Xavier, in the city of Sucre.[1]

Political baptism

Linares was seventeen years old when, on the night of 13 July 1825, a revolutionary movement erupted in the city of Potosí in support of Antonio José de Sucre and Francisco O'Connor, who were approaching the city as part of the Upper Peruvian campaign of the Bolivian War of Independence. Leaving his home, Linares joined the Patriot cause, which eventually succeeded in overthrowing the Spanish Royalists in Upper Peru. This moment served as Linares' first political involvement; after the revolution, he continued to support liberal movements, governments, and ideologies.[2][3]

Physical appearance

Regarding his appearance, Carlos Walker Martinez describes Linares as possessing an imposing stature and a somewhat slender build. His nose, aquiline and well-defined, added to the distinguished impression; his forehead, broad and unmarked forehead, which was believed by Walker to have hinted at a lack of necessity to conceal his thoughts. His open mouth, consistently adorned with a smile, contributed to an inviting demeanor. His complexion bore a slightly dark hue due to his Andalusian heritage, and his eyes were deep and black. Linares is also noted by Walker as having had wide eyes when giving a speech, exhibiting an extraordinary brilliance that captivated onlookers.[4]

Political career

In the final years of General Andrés de Santa Cruz's administration, a powerful party emerged in Bolivia, the National Party, which did not support the Peru–Bolivian Confederation and openly conspired against its Protector. The revolution against him finally erupted at an inconvenient moment for Santa Cruz, leading to the loss of his control in Bolivia. Simultaneously, in Peru, the Chileans, under the command of General Manuel Bulnes, expelled Santa Cruz. The pronunciamientos of José Miguel de Velasco and José Ballivián took place on 9 February and 15 February respectively, and the Battle of Yungay on 20 January 1839.[5] With Santa Cruz and his Confederation fallen, General Velasco rose to power. Around him, the most notable figures in the country gathered, including Linares.[6] With them, an independent congress was established, contrasting sharply with previous assemblies.[7][8]

This assembly, in stark contrast to Santa Cruz's policies, completely reformulated the country's governmental structure. Linares and his involvement in contributing to this constitution were applauded. His popularity increased significantly as a result, and after a short stint as Prefect of the Department of Potosí, he was called to assume the position of Minister of the Interior and Foreign Relations: "In taking this measure," stated Velasco in a communication dated 16 November 1839, "announcing to you your appointment, I have considered not only the notorious capacity and deep patriotism that you embody but also the outstanding and relevant services you have rendered to the cause of Bolivia's restoration".[9]

Minister of the Interior and Foreign Relations

.jpg.webp)

Finding the country in a state of chaos, Linares had to contain the revolutionary attempts of General Ballivián and the former allies of the fallen Protector, who seized every opportunity to sway public opinion in their favor.[10] Another crisis unfolded with Peru, where President Agustín Gamarra had plans to conquer Bolivia. Linares, in his function as Minister of the Interior and Foreign Relations, refused to ratify the humiliating treaties imposed by Peru, signed in 1829, and prepared for war. Gamarra responded by crossing the Desaguadero with a sizable army, militarily occupying the departments of La Paz and Oruro. Velasco and Linares did everything possible, with the support of the congress, to organize a resistence against the invading army. However, a revolutionary movement erupted in the south led by General Sebastián Ágreda, a supporter of Santa Cruz. Ballivián, in hiding but not defeated, raised arms in the same invaded departments; civil discord spread rapidly, and internal conspiracies hindered responses to external attacks. Velasco and his government, thus, collapsed, and on 10 June 1841, Linares was forced to resign. Public opinion, however, raised Linares' name amid the turmoil with honorable applause. Velasco was on the Argentine border with a respectable force he had managed to gather around him, preparing to meet Ballivián, who had already been proclaimed president by the revolutionaries. At that moment, Velasco received news that the common enemy, General Gamarra, was facing the Bolivian Army on the eve of a decisive battle. Velasco, with Linares' support, spontaneously decided to hand over his entire army to Ballivián, an act that proved decisive and culminated in the Bolivian victory on the fields of Ingavi on 18 November 1841.[11]

Exile in Europe

Meanwhile, Linares embarked on a journey to Europe. There, he divided his time in exile between serious studies, to which he devoted himself, and family matters that required resolution before the courts of Navarre. The ancestral wealth of his affluent grandparents was at risk of falling into the hands of the local government. Lengthy legal disputes had unfolded in previous years, and now was the opportunity to bring them to a close. He obtained the reparations sought and regained possession of his property. The letters he wrote to his friends in America reveal the kind of studies that particularly occupied his time. Social science was the focus of his vigilance. Linares believed that he foresaw the coming revolution and studied it, using a "sure scalpel to expose the deep wounds of European society".[12] Subsequent events confirmed his assertions when the Revolutions of 1848 erupted.

Spain recognizes Bolivian independence

In 1847, while still in Europe, Linares received the appointment of plenipotentiary minister of Bolivia to Spain. Invested with this position, he negotiated a treaty of peace and friendship with the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Spanish court, Don Joaquín Francisco Pacheco, in which the independence of Bolivia was recognized.[13] However, this pact was not ratified by the Bolivian government because Manuel Isidoro Belzu refused to do so, considering it tainted since it had been negotiated by General Ballivián, who was now out of favor.[14] During Linares' absence, Bolivia had undergone drastic changes with violent reactions and acclaim for tireless caudillos. Having lost his popularity, Ballivián and his successor, Eusebio Guilarte, were overthrown by Velasco and Belzu. Once again acclaimed in the southern departments as the constitutional president, Velasco assumed the presidency while Belzu was appointed Minister of War. Linares returned to Bolivia after Ballivián's fall and was elected President of the Bolivian Congress.[15] According to the provisions of the 1839 Constitution, now in force, Linares was, de facto, the Vice President of Bolivia.[16]

Relentless plotter

However, just a few months later, Belzu, who had contributed more than anyone to overthrow Ballivián and had initially supported Velasco's proclamation, led a revolution in Oruro and proclaimed himself President of Bolivia. In the Battle of Yamparáez on 6 December 1848, Belzu defeated the government forces personally commanded by General Velasco, after a three-month campaign. Velasco, defeated, handed over the leadership of the constitutionalist cause to Linares.[17] Soon thereafter, he became leader of the so-called Partido Generador (Generator Party), which advocated democracy, civilian control of politics, and a return of the Bolivian military to its barracks. This earned Linares the mistrust of most governments of the time (which were de facto), and a few stints in exile. Nevertheless, he became the country's most important civilian and constitutionalist leader, with a growing following.[18] Exiled from Bolivia, Linares spent almost a decade conspiring against the government of Belzu.[19] His tireless conspiracies are described by Walker Martinez in the following words:

One could see him in Salta gathering around him some outcasts and invading the borders of Bolivia, crossing rough roads, ravines, and deep rivers, vast deserts, and facing all kinds of dangers. Then, when Belzu's forces shattered his weak and naturally ill-prepared armies in those improvised campaigns, and the triumphant leader believed his enemy was reduced to impotence and completely annihilated, he could be found on the shores of Chile, or on the coasts of Peru, weaving the threads of another revolution, gathering the broken and scattered fragments of Bolivia's old parties, and arming his followers to attempt a coup. When his calculations failed again and when no hope seemed to remain amid the wreckage of his plans, his health, and his fortune, he would be found again in astonishment in Salta, in Tucumán, in Buenos Aires, in Copiapó, in Santiago, and in Tacna, always waging relentless war against his enemy, relentlessly pursuing the same object without deviating an inch from his goal.[20]

Juan Manuel de Rosas, at Belzu's request, became involved in the matter. Linares was forced to reside in Buenos Aires and was subjected there for a year under the strictest surveillance. The Battle of Caseros on 3 February 1852, and the fall of Rosas freed Linares from his captors in Buenos Aires. Once free, he continued his relentless plots. In 1853, when he traveled from Salta to Valparaíso during the winter, a friend described the following: "He had lost his beard and eyebrows in the ice of the mountains; his skin was so tanned that he seemed completely black, his lips torn apart, his nature, in short, shattered but not defeated".[21] In his later years, the effects of these harsh and long journeys throughout South America manifested as severely compromised health.[22]

Battle of Tupiza

Amidst the many small skirmishes and countless minor battles of that prolonged conflict, Linares arrived in the province of Chichas and reached Tupiza when least expected. He arrived in the evening and, without dismounting from his horse, spoke words that motivated his soldiers. The next morning, he prepared for battle because General Jorge Córdova was rapidly advancing against the revolution and was at the gates of the town. Three days later, the forces of both sides met on the fields of Mojo on 8 July 1853. Linares' forces could not defeat the seasoned Córdova, who triumphed against the rebels in twenty minutes. During the battle, the cavalry, which comprised the majority of the revolutionary forces, rode on horses not yet entirely tamed, leading to great disorder at the first cannon shots.[23] The efforts of the leaders to restore the line and take timely action were in vain. Colonel Tejerina, the commander of those troops, in his despair, charged with only thirty men against Córdova's unit and met his end amidst enemy bayonets. General Manuel Carrasco, upon witnessing the defeat, charged the enemy ranks, came within a few steps, fired his pistols, and fled. Among the other revolutionary leaders were the former president Velasco and Casimiro Olañeta.[24]

Presidency of Jorge Córdova and the Oruro Revolution

.jpg.webp)

However, while these campaigns had failed, they were not in vain because they achieved the objective–to wear down Belzu. Over the course of nine years, Linares had launched thirty-three revolutions against the government of Belzu.[25] None of these culminated in the overthrow of Belzu. Yet, they the tired caudillo did not wish to continue policing Linares' revolutionary activity. Weary of the struggle, the leader surrendered and handed over command to his son-in-law, General Córdova.[26] In his message to the Congress of 1855, Belzu stated: "I solemnly protest that no consideration will compel me to continue holding an office that has become unbearable, absolutely unbearable, yes, a thousand times unbearable!"[27] After Belzu's resignation, the belicista party organized the General Elections of 1855, where Córdova emerged as the winner and Linares in second place. Córdova received 9,388 votes, Linares 4,119, Celedonio Ávila 300, and Gonzalo García Lanza 282.[28] The General Elections of 1855 inaugurated Córdova as Constitutional President, although Linares and his followers did not view this result as legitimate. Believing the election results to have been manipulated, Linares' conspiracies continued inside and outside Bolivia. In the span of two years, Linares orchestrated over a dozen uprisings. In 1855, Córdova, who was rushing to campaign in the north and had barely returned to the capital, "heard the distant clamor of the insurgents in the southern provinces".[29] On the Argentine border, Linares staged three simultaneous revolutions against Córdova, while Oruro and La Paz were again targeted by attacks from Tacna. In December 1856, Linares crossed into Chile through the Copiapó mountain range and then to Tacna, where he arrived in mid-1857. At that time, he had received reliable reports on the internal situation of Bolivia, knew how much the demoralized government of Córdova had fallen into disrepute, and judged the occasion opportune to overthrow the belicista regime. Linares launched his coup in Oruro, on 8 September 1857.[30]

The news of the Oruro Revolution, which quickly spread from one end to the other of the Republic, sparked a massive uprising against Córdova. Two causes contributed to this: Córdova's lack of popularity and the constitutionality of the Partido Generador, considered by some as the legal continuation of Velasco's government. The masses saw Linares as the legalist cause, tired of the caudillismo and internal wars that had plagued Bolivia for decades. Linares' cause obtained eighty thousand signatures on its revolutionary acts, legitimizing his coup against Córdova. Once Oruro fell into Linares' hands, the revolutionary fervor in the rest of the country grew exponentially. Linares headed towards Cochabamba, whose entire population rebelled under the command of General Dámaso Bilbao la Vieja, erecting barricades in the streets of the city and proclaiming the linarista cause. Córdova, along with General Ambrosio Peñailillo, led a respectable division from Sucre to eliminate the insurgents. A bloody battle ensued in the various attacks that Córdova launched upon Cochabamba. Amidst the smoke of battle, Linares encouraged his troops by example and word. His figure itself appeared before his troops in the midst of shrapnel bursts and gunpowder smoke. Córdova withdrew from the main square, and with his troops defeated in various encounters in other parts of Bolivia, he was forced to seek refuge on the borders of Peru. On 31 March 1858, months after overthrowing Belzu's son-in-law, Linares declared himself dictator.[31] His first acts as President were to abolish belcista fiscal policies regarding internal debt,[32] a major problem for the government in the first fourty years since Bolivian independence.[33]

President of Bolivia

Fiscal, structural, ecclesiastical, and judicial reforms

During Linares' government, a movement of constitutionalist civilians known as the rojos emerged.[34] This movement included politicians like Mariano Baptista and Adolfo Ballivián, who later governed as president leading the Partido Rojo (Red Party). Prefectures and high administrative and judicial positions were occupied by individuals who shared Linares' "regenerative" ideology; they believed the country needed a radical reform to emerge from the chaos they perceived. His cabinet was formed as follows: finance, Tomás Frías; foreign relations and public instruction, Lucas Mendoza de la Tapia; development, Manuel Buitrago; war, General Gregorio Pérez; and government, cult, and justice, Ruperto Fernández. Later, the Ministry of Public Instruction was taken over by Evaristo Valle, and the Ministry of War by General José María de Achá.[35]

The country's finances, which were in ruins, quickly improved thanks to the strict austerity introduced in expenditures, and thus the national credit rose a few degrees from the deplorable state it was in. Although the 1860 expenditure budget, totaling 2,339,704 pesos, exceeded the revenues by 115,417 pesos, which was a huge deficit, Frías managed to balance expenses with revenues within a short time.[36] To reduce spenditures, the army was reduced from 5,000 active personnel to just 1,500.[37] Means were also sought to pay off the internal public debt, which had been completely forgotten until then; free export of gold and other metals was allowed, and Frías was tasked with drafting a mining code needed by the country.[38] The quina bank was abolished, making the export of quinine open and easy for everyone; coins were introduced into circulation to remedy the circulation of weak currency, giving rise to the name pesos-Frías, named after the minister who designed them. Tariffs on imported foreign fabrics through Arica and Cobija were reduced; regulations for joint-stock companies were also determined; and, among many other measures, the realization of a loan of one million pounds sterling in Europe was initiated, intended for the canalization of the Desaguadero and the construction of a road that, starting from this point, would reach the Bolivian coast. This would bring the cities of La Paz, Oruro, and Potosí within reach of the sea.[39] Linares' fall prevented the loan from being realized when the business was almost entirely concluded.[40]

Regarding the reformation of the clergy, which was in a very low state, Linares applied liberal and secular ideas. Of these ecclesiastical reforms, Linares said the following: "Given the powerful influence of the clergy among us, would the regeneration of the country be possible without its reform? No; and for this purpose, among other measures, I undertook the establishment of large seminaries... Seeing temples in ruins, others converted into pigsties, and the bride in rags and the concubine in finery, could I not be filled with indignation? I felt it because I am convinced of what corresponds to the greatness of the Being we worship in the temples and of how the poor state of it not only serves to cool devotion but also destroys the religious spirit".[41] The action cost Linares a great deal of his popularity, since so many Bolivians, devoutly Catholic, saw the act as villainous.[42]

The Ministry of Justice also implemented significant reforms during Linares' era. A new law on judicial organization came into effect, completely changing the old system. It established a court of cassation, three courts of appeals, and twelve district courts, each composed of three members and a prosecutor. A new criminal code was enacted, and various provisions were issued regarding the better organization of public offices, the creation of special commercial courts, salaries, and the accountability of employees, as well as regulations for the practice of law.[43] The new territorial division and the organization of municipalities were another important reform during the Linares era.[44]

Relations with Peru

The Linares administration was plagued with the same poor relations with Peru as had previous ones. The intrigues of Lima had a significant influence on the events in Bolivia, especially during the first fourty years since independence. The armed interventions of both countries, such as the revolution of Chuquisaca in 1828 and Sucre's resignation from the presidency of Bolivia, were strongly influenced by Peruvian politics and Gamarra's invasion. The intrigues of Gamarra and Luis José de Orbegoso brought about the conflict with Felipe Santiago Salaverry and the creation of the Peru–Bolivian Confederation. When Gamarra returned to power, he resumed hostilities with Bolivia, encouraging the ambitions of some political exiles. At the same time, he pretended to desire a diplomatic settlement that was never fulfilled. Linares, who at the time was Minister of the Interior and Foreign Affairs, was all too aware of the danger Gamarra posed and believed Lima's intentions were deceitful. Despite the victory at Ingavi, defeating the Peruvian forces and the death of Gamarra, diplomatic hostilities persisted well into the Linares administration. Historian Ramón Sotomayor Valdés describes the tensions as follows: "Since then, on Peruvian soil, a natural refuge for fugitives and emigrants from Bolivia, they found not only security but also facilities to conspire and constantly threaten the public order of their homeland. Bolivia soon adopted, in retaliation, this tactic, as it became a custom for dissidents from the government of one Republic to find in the government of the other an interested protector or a more or less decided accomplice".[45] When Ballivián fell, a new conflict with Peru was lurking on the horizon; a conflict in which Bolivia planned to acquire the departments of Moquegua and Tarapacá, considered natural and almost necessary boundaries to complete Bolivian territory. Such territorial acquisitions were supported by Linares.[46] Ramón Castilla, to assume the presidency of Peru, was aided by Belzu. Subsequently, Belzu and his supporters relied on Castilla to regain power. The distrust between Peru and Bolivia originated from these conspiracies between their respective diplomatic offices. When Castilla had come to rule in Peru, and although he was a friend of Belzu, he wanted to avenge Peru's defeat at Ingavi for personal reasons. After Ingavi, Castilla was taken prisoner, transported to Oruro, then to Cochabamba, and finally to Santa Cruz, where he spent a year as a prisoner. Therefore, Castilla was planning another war with Bolivia by the time Linares had come to power in 1857. Tensions even after Linares was removed in 1861, relations remaining strained until 1867.[47]

To put an end to the complaints from the Peruvian government, Linares sent Ruperto Fernández as a plenipotentiary to Lima. In January 1859, he carried out an agreement in which both governments committed to preventing any attempt at revolution and invasion in each other's territory by political exiles. This agreement was particularly beneficial for Bolivia since, in the same days it was signed in Lima, open conspiracies were underway in Tacna and Puno with the purpose of invading Bolivian territory. Despite the agreement, the Peruvian government ignored these conspiracies and allowed the passage of Bolivian revolutionaries, who brought an armed force into Bolivia under the command of former President Córdova and General Ágreda. For this reason, the agreement was not accepted. Fernández, after demanding explanations about Castilla's conduct without success, requested his passports and returned to La Paz. Linares then severed communications with Peru on 14 May 1860, and maintained an absolute interdiction, preparing for war and increasing its military forces.[48] The situation became more strained for Bolivia since, being an isolated country, all its foreign consumer goods were imported through the port of Arica. Peru lost little to nothing, except for the maintenance of the army near the Bolivian borders, which, while primarily intended to monitor Bolivia's government movements, also served to control the revolutionary advances of Arequipa and Cuzco, departments hostile to Castilla's administration. Linares tried to remedy the import blockade by reopening trade between the two countries, while still maintaining severed diplomatic relations and continuing to strengthen his troops. His fixed and constant intention was to invade Peru sooner or later. He was pleased with the idea of completing the "natural boundaries of Bolivia" and carrying out the plan that Santa Cruz did not realize.[49]

Revolutions against Linares

In August 1858, the first rebellion against Linares erupted in La Paz. The plan involved assassinating the dictator and immediately inciting a rebellion among the troops. To execute the plan, on the morning of 10 August, some rebels positioned themselves in the main square in front of the Palacio Quemado, others in the side street running south, and the rest were ready to assault the barracks at the opportune moment. As the commotion outside grew, Linares, who was at that moment in the palace hall facing the square, rushed to see what was happening, just as the revolutionaries gathered at the foot of the windows. Juan José Prudencio, a general loyal to Linares, who was with the dictator at the time, advanced toward balcony before Linares. At the moment he made this movement and just as he reached the railings, a rifle bullet pierced his chest, leaving him lifeless on the spot.[50] Linares, eager to control the tumult with his presence, insisted on going out to the same balcony. But those with him prevented this. A few more bullets crossed the air, one of which fatally wounded the aide-de-camp, Colonel Viruet, who imprudently had leaned out of another window.[51] The palace guard came out, opened fire on the rioters, and made them flee within minutes. Some of the accomplices of the crime were captured, necessary investigations were conducted, and after a process strictly adhering to the law, some were sentenced to death, including a Franciscan friar named Porcel, who had a questionable background. The fatal sentence imposed on the friar stirred compassion in some people who made vigorous efforts to have it suspended, considering he was a holy man. However, nothing succeeded in swaying Linares' will, as he refused to make a favorable exception for the friar, who, for the same reasons pleaded for his salvation, turned out to be the most criminal of the convicts. The friar was degraded according to the provisions of canon law and was promptly executed by firing squad.[52]

The following year witnessed another revolution; Generals Córdova and Ágreda brought to Bolivia what was called called a cruzada (Crusade), a curious name given to any invasion by political exiles to overthrow the established government. They brought men and war materials from Peru and crossed the border. Linares, who was then in Oruro and learned of the event, swiftly set things in motion. The two army forces, the revolutionaries and the government forces, met on the heights of La Paz on the same day, so that Córdova and Ágreda descended to the city from the northern hills at the same time that Linares descended from the road called "de Potosí".[53] The battle broke out on the slopes of the "Calvario," ten or twelve blocks from the main square; it did not last long because the revolutionary forces were inferior, and they were completely defeated. The leaders fled to Peru. The government showed clemency towards the prisoners. In this revolution, it seems beyond doubt that Peruvian authorities played some part, at least tolerating and sympathizing with the preparations and leaders of the cruzada by the belicistas.[54] With these revolutions extinguished, the government appeared more powerful and stable than ever. Linares, after making a journey across the country, studying its geography, considered summoning Congress. He believed that to complete his 'work,' it was necessary for him to account for his actions before the National Assembly.[55]

Overthrow, exile, and death

After continuous riots, conspiracies, and uprisings, it was finally on 14 January 1861, that Linares would be overthrown. Since dawn that day, vague and ominous rumors circulated in the city of La Paz, a peculiar and strange movement was noticed in the barracks, and more people than usual were seen entering and leaving the Palacio Quemado. No one knew what was happening, but Linares sensed something serious. The crowd roamed the square and on street corners to find out what was going on. Meanwhile, inside the palace, a different scene was taking place. Linares, in a low voice, read a communication that had just been delivered to him, bearing the signatures of his two ministers, Achá and Fernández, and the Inspector General of the Army, General Manuel Antonio Sánchez. The names at the bottom did not reveal the content of the writing. However, in a few lines, it stated that Linares had been removed from power. The crowd learned what was really happening when Linares, accompanied by a few friends, left the palace to seek asylum in a neighboring house. The rebellious battalions in the square proclaimed the triumvirate of Achá, Sánchez, and Fernández. Among the leaders who participated alongside the triumvirate were Narciso Campero, Plácido Yáñez, Adolfo Ballivián, and Benjamin Rivas.[56] The treason of Linares' ministers marked the end of the linarista dictatorship. Known for his energetic and indomitable personality, Linares did not attempt to regain power as he was seriously ill. Although Linares did not react, the rojos proposed some counter-revolutionary plan to Frías, which, rather than being a well-thought-out plan based on solid foundations, was a generous suggestion with little chance of success. Frías did not deem it prudent to accept this futile sacrifice. Some leaders scattered in various military districts tried to unite for a joint action. However, these efforts did not succeed. With illness plaguing him, Linares had no choice but to go into exile. He left La Paz six days after his downfall, on 20 January 1861. Some loyal friends accompanied him to El Alto, bidding him farewell at the foot of the Illimani.[57]

In his message addressed to the Congress of Bolivia, Linares expressed his wishes, ideas, and perspective about the country and its future:[58]

Sirs: Not because I harbor the desire to rule again, much less any sinister intention, do I address you today, for in uncorrupted hearts, there is no room for anything unworthy, and the leadership, while I had it, was for me nothing but a torment, to which I could only have resigned myself due to my ardent love for Bolivia and my eagerness to seek the common good. I exercise a right that I have not lost: I fulfill a sacred duty. I have been the leader of the beautiful September revolution and held the reins of government for more than three years. Since the age of seventeen, I have served our homeland, always forgetting myself and sacrificing for its happiness everything dear to a man. The object of my most fervent wishes will be its well-being as long as I live... I disregard pretense, detest hypocrisy, and truth in everything is the rule of my conduct, and in accordance with it, I am going to give an account of all my actions while I held power. The examination must be scrupulous and severe, and in your name, for Bolivia's credit and the luster of the September revolution, I demand that you do so.[59]

Months after sending this letter, Linares died in Valparaíso on 23 October 1861, after his already declining health deteriorated.[60] Mariano Baptista, the last politician who remained loyal to Linares until the end, was by his side.[61]

Bilbiography

- Alcázar, Moisés (1967). Paginas de Sangre; Episodios Tragicos de la Historia de Bolivia. Ediciones Puerta del Sol.

- Basadre, Jorge (1983). Historia de la República del Perú, 1822-1933 (in Spanish). Editorial Universitaria.

- Crabtree, John; Gray Molina, George; Whitehead, Laurence, eds. (2009). Tensiones irresueltas: Bolivia, pasado y presente (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99954-1-229-6.

- Díaz Arguedas, Julio (1929). Los generales de Bolivia (rasgos biográficos) 1825-1925: prólogo de Juan Francisco Bedregal (in Spanish). Imp. Intendencia General de Guerra.

- Kieffer Guzmán, Fernando (1991). Ingavi: batalla triunfal por la soberanía boliviana (in Spanish). EDVIL.

- Klein, Herbert S. (3 February 2003). A Concise History of Bolivia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00294-3.

- Langer, Erick D. (19 August 2009). Expecting Pears from an Elm Tree: Franciscan Missions on the Chiriguano Frontier in the Heart of South America, 1830–1949. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-9091-6.

- Morales, Waltraud Q. (14 May 2014). A Brief History of Bolivia. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0820-9.

- Parkerson, Phillip Taylor (1984). Andrés de Santa Cruz y la Confederación Perú-Boliviana, 1835-1839 (in Spanish). Libreria Editorial "Juventud".

- Peralta Ruiz, Víctor; Irurozqui Victoriano, Marta (2000). Por la concordia, la fusión y el unitarismo: estado y caudillismo en Bolivia, 1825-1880 (in Spanish). Editorial CSIC - CSIC Press. ISBN 978-84-00-07868-3.

- Shchelchkov, A. A. (2011). La utopía social conservadora en Bolivia: el gobierno de Manuel Isidoro Belzu 1848-1855 (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99954-1-326-2.

- Vázquez Machicado, Humberto (1991). La diplomacia boliviana en la corte de Isabel II de España: la mision de José María Linares (in Spanish). Libreria Editorial "Juventud,".

- Walker Martínez, Carlos (1877). El dictador Linares: biografía (in Spanish). "La Estrella de Chile.

References

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, p. 12.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, p. 13.

- ↑ Parkerson 1984, p. 320.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, p. 14.

- ↑ Parkerson 1984, pp. 299–301.

- ↑ Vázquez Machicado 1991, p. 63.

- ↑ Barragán, Rossana (2015). Bolivia, su historia, Tomo IV: Los primeros cien años de la República1825-1925. p. 63.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, p. 15.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 15–16; Parkerson 1984, pp. 307–309.

- ↑ Kieffer Guzmán 1991, p. 5.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 16–17; Kieffer Guzmán 1991, pp. 459–462.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, p. 18.

- ↑ Vázquez Machicado 1991, p. 122.

- ↑ Vázquez Machicado 1991, pp. 127–135.

- ↑ Shchelchkov 2011, p. 106.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Langer 2009, p. 32.

- ↑ Crabtree, Gray Molina & Whitehead 2009, p. 147.

- ↑ Shchelchkov 2011, p. 115–116.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Crabtree, Gray Molina & Whitehead 2009, p. 155.

- ↑ Crabtree, Gray Molina & Whitehead 2009, pp. 155–157.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 24–25; Crabtree, Gray Molina & Whitehead 2009, p. 157.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, p. 11.

- ↑ Shchelchkov 2011, pp. 266–26.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Shchelchkov 2011, p. 271; Morales 2014, p. 63.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, p. 28.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 27–31.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 32–33; Peralta Ruiz & Irurozqui Victoriano 2000, pp. 47–49.

- ↑ Shchelchkov 2011, p. 184.

- ↑ Peralta Ruiz & Irurozqui Victoriano 2000, p. 84.

- ↑ Klein 2003, p. 138.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 38–40; Crabtree, Gray Molina & Whitehead 2009, p. 182.

- ↑ Peralta Ruiz & Irurozqui Victoriano 2000, p. 102.

- ↑ Klein 2003, p. 129.

- ↑ Klein 2003, p. 130; Morales 2014, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Crabtree, Gray Molina & Whitehead 2009, pp. 182–188.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 42–43; Crabtree, Gray Molina & Whitehead 2009, p. 192.

- ↑ Langer 2009, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Peralta Ruiz & Irurozqui Victoriano 2000, p. 73; Crabtree, Gray Molina & Whitehead 2009, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 43–44; Crabtree, Gray Molina & Whitehead 2009, pp. 196–199; Langer 2009, p. 23.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, p. 46.

- ↑ Peralta Ruiz & Irurozqui Victoriano 2000, p. 128.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 46–47; Peralta Ruiz & Irurozqui Victoriano 2000, p. 130.

- ↑ Basadre 1983, p. 167.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 47–49.

- ↑ Díaz Arguedas 1929, pp. 611–612.

- ↑ Alcázar 1967, p. 110.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Díaz Arguedas 1929, p. 72.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, p. 56.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 60–62; Peralta Ruiz & Irurozqui Victoriano 2000, p. 50.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Linares, José Maria (1861). Mensaje que dirije el ciudadano José María Linares a la Convencion boliviana de 1861 (in Spanish). Impr. i libreria del Mercurio de Santos Tornero. Archived from the original on 29 December 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ↑ Vázquez Machicado 1991, p. 136.

- ↑ Walker Martínez 1877, pp. 64–66.