Joseph Knibb | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1640 |

| Died | 1711 |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation(s) | Clock- and watchmaker |

| Known for | inventor of Roman striking, tic-tac escapement and probably anchor escapement |

Joseph Knibb (1640–1711) was an English clockmaker of the Restoration era. According to author Herbert Cescinsky, a leading authority on English clocks, Knibb, "next to Tompion, must be regarded as the greatest horologist of his time."[1]

Life and work

He was born in 1640, the fifth son of Thomas Knibb, yeoman of Claydon.[2] He was cousin to Samuel Knibb, clockmaker, to whom he may have been apprenticed in about 1655.[2] After serving his seven years he moved to Oxford in 1663, the year Samuel moved to London.[2]

Knibb set up premises in St Clement's, Oxford, where he was outside the city liberties.[2] In 1665 or 1666 he moved to premises in Holywell Street, which was within the city liberties.[2] The freemen of the city objected to his presence,[2] demanding that he "suddenly shut his windows" because he was not a freeman of the city.

Knibb applied for the Freedom of Oxford twice in 1667 but on both occasions the smiths and watchmakers of the city objected and he was refused.[2] In February 1668 he was finally admitted to the freedom in a compromise arrangement in which he was officially recorded as being employed by Trinity College, Oxford as a gardener and paid a fine of 20 nobles (£6.13s.4d.) and a leather bucket.[3]

In 1669 Wadham College, Oxford had a new turret clock built and from 1671 to 1721 Knibb's younger brother John was paid £1 per year to maintain it.[4] It is the earliest surviving clock with an anchor escapement, and may even be the first such clock ever built.[5] In 1954 the antiquarian horologist Dr. C.F.C. Beeson proposed the theory that Joseph Knibb had built the clock.[5] Beeson's theory has since become widely accepted.[5]

By 1670 Knibb had moved to London where he was made free of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.[3] Initially he set up business at the Dyal, near Serjeant's Inn in Fleet Street, subsequently moving to the House at the Dyal, in Suffolk Street. He was elected as a steward of the Clockmakers Company in August 1684 and assistant in July 1689. He retired from London in 1697 and went to live in Hanslope in Buckinghamshire, where he continued to make clocks until his death in 1711.[3]

Reputation and legacy

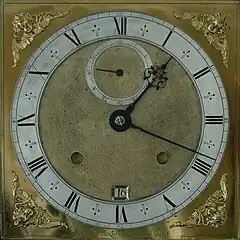

Joseph Knibb is renowned for both the quality of his work and his invention. The aesthetic beauty and simplicity of his work is unparalleled. Among his many inventions was the system of Roman striking,[6] the tic-tac escapement, and probably the anchor escapement.[7] His merits were recognised by his being appointed clockmaker to Charles II and then to James II.

Clock cases of Knibb's era were wooden, and therefore were made by specialist clockcase makers who were members of the Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers.[8] The politician Richard Legh (1635–87) wrote to his wife describing Knibb's advice on choosing a case for a longcase clock:

I went to the famous Pendulum maker Knibb, and have agreed for one, he having none ready but a dull stager which was at £19; for £5 more I have agreed for one finer than my Father's, and it is to be better furnished with carved capitalls gold, and gold pedestalls with figures of boys and cherubimes[9] all brass gilt. I wold have had itt Olive Wood, (the Case I mean), but gold does not agree with that colour, soe took their advice to have it black Ebony which suits your Cabinett better than Walnut tree wood, of which they are mostly made. Lett me have thy advice by the next.[10]

Legh's young wife, Elizabeth, replied in agreement: "My dearest Soule; as for the Pandolome Case I think Blacke suits anything".[10]

Joseph Knibb is the most accomplished of an extended family of clockmakers that included his cousin Samuel and Joseph's younger brother John. A younger cousin Peter Knibb (1651–79) from Farnborough, Warwickshire was apprenticed to Joseph in 1668[3] and became a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers in 1677.[11] John Knibb's youngest son, also called Joseph (1695–1722)[11] was apprenticed in London in 1710 and received a substantial bequest from the elder Joseph Knibb's will[11] in 1712. Another cousin, Elizabeth Knibb from Collingtree, Northamptonshire, married another clockmaker, Samuel Aldworth, in 1703.[12] Aldworth had been in Oxford as John Knibb's apprentice and then assistant.[13] In 1697 Aldworth moved from Oxford to London to succeed Joseph Knibb on the latter's retirement to Hanslope.[13]

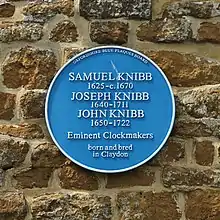

On 26 September 2010 the Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board unveiled a blue plaque at Claydon to Samuel, Joseph and John Knibb.[14]

On 6 November 2012 Sotheby's sold a small Roman striking table clock by Knibb from the George Daniels collection for £1,273,250.[15]

References

- ↑ "A Long-case clock by Joseph Knibb". Burlington Magazine. 1919. Retrieved 14 November 2019. For an article describing Cescinsky as a leading authority, see "Article mentioning Cescinsky". Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Beeson 1989, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 4 Beeson 1989, p. 123.

- ↑ Beeson 1989, p. 65.

- 1 2 3 Beeson 1989, p. 2.

- ↑ Symonds 1947, p. 47.

- ↑ "'Clocks' by David Thompson, London, 2004, p.76 as quoted on British Museum website (go to "Curator's Comments" and click "More")". British Museum. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ↑ Symonds 1947, p. 52.

- ↑ Legh probably used "cherubimes" to refer to what are more properly called putti.

- 1 2 Symonds 1947, p. 53.

- 1 2 3 Beeson 1989, p. 124.

- ↑ Beeson 1989, p. 176.

- 1 2 Beeson 1989, p. 85.

- ↑ "Samuel, Joseph and John KNIBB". Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Scheme. Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board. 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ↑ "Standing room only at Sotheby's London as the George Daniels horological collection totals £8,285,139" (PDF). Sotheby's. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

Sources

- Beeson, CFC (1989) [1962]. Simcock, AV (ed.). Clockmaking in Oxfordshire 1400–1850 (3rd ed.). Oxford: Museum of the History of Science. pp. 122–124. ISBN 0-903364-06-9.

- Cescinsky, Herbert (1938). Old English Master Clockmakers and Their Clocks 1670 to 1820. London: George Routledge and Co.

- Dawson, Percy G; Drover, CB; Parkes, DW (1994) [1982]. Early English Clocks – A Discussion of Domestic Clocks up to the Beginning of the Eighteenth Century. Woodbridge: The Antique Collectors' Club.

- Lee, RA (1964). The Knibb Family, Clockmakers Or: Automatopaei Knibb Familiaei. The Manor House Press.

- Loomes, Brian (1999) [1982]. The Early Clockmakers of Great Britain. Tonbridge: Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 0719802008.

- Symonds, RW (1947). Pevsner, Nikolaus (ed.). A Book of English Clocks. The King Penguin Books. Vol. K28. Harmondsworth & New York: Penguin Books.

- Ullyett, Kenneth (1950). In Quest of Clocks. London: Rockliff Publishing Corporation Ltd. pp. 9, 33, 37, 131–134.

- Numerous articles and references in Antiquarian Horology, quarterly journal of the Antiquarian Horological Society