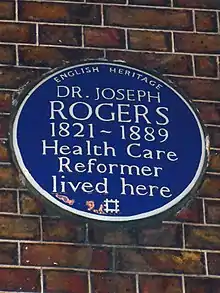

Joseph Rogers (1821–1889) was an English physician and campaigning medical officer.

Life

The elder brother of Thorold Rogers, he was born at West Meon, Hampshire.[1] For 40 years Rogers promoted reform in the administration of the Poor Law. Beginning a medical practice in London in 1844, he became supernumerary medical officer at St Anne's, Soho, in 1855, on the occasion of an outbreak of cholera. The following year he was appointed medical officer to the Strand workhouse.[2]

The conditions in the Strand workhouse had been found very bad by the future reformer Louisa Twining, when she visited in 1853.[3] Rogers had the workhouse master George Catch removed, on the grounds that Catch had delayed calling a doctor for a woman in pain giving birth, to save money.[4]

In 1861 Rogers came before the select committee of the House of Commons, speaking on the supply of drugs in workhouse infirmaries, and his views were adopted.[2] Much of the evidence on which Gathorne Hardy relied in pushing for the Metropolitan Poor Act 1867 came from Rogers.[5] In 1868 zeal for reform brought him, however, into conflict with the guardians, and the president of the poor-law board, after an inquiry, removed him from office. In 1872 he became medical officer of the Westminster Infirmary. Here also the guardians resented his efforts at reform and suspended him, but he was reinstated by the president of the poor-law board, and admirers presented him with a testimonial.[2]

Rogers was appointed in 1872 to the Westminster workhouse, where his predecessor French told him he had dispensed only a placebo for 40 years, keeping the entire drugs budget.[6] He was the founder and for some time president of the Poor Law Medical Officers Association. He helped to establish the Association for the Improvement of the Infirmaries of London Workhouses[7] The system of poor-law dispensaries and separate sick wards, with proper staffs of medical attendants and nurses, was due to the efforts of Rogers and his colleagues. He died in April 1889. His Reminiscences were edited by his brother Thorold.[2]

Notes

- ↑ Ledingham, John G. G. "Rogers, Joseph". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23989. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 4 Lee, Sidney, ed. (1897). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 49. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ Helen Rappaport (2001). Encyclopedia of Women Social Reformers. ABC-CLIO. p. 720. ISBN 978-1-57607-101-4.

- ↑ Simon Fowler (11 September 2014). The Workhouse: The People, The Places, The Life Behind Doors. Pen and Sword. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-78383-151-7.

- ↑ Ruth G. Hodgkinson (1967). The origins of the National Health Service: the medical services of the new Poor Law, 1834-1871. University of California Press. p. 304. GGKEY:3N81XYYUF3A.

- ↑ Deborah Kirklin; Ruth Richardson (2001). Medical Humanities: A Practical Introduction. Royal College of Physicians. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-86016-147-6.

- ↑ "Dickens, Rogers and Miss Nightingale". King's Collections. King's College London. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

External links

- Works by Joseph Rogers at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1897). "Rogers, James Edwin Thorold". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 49. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1897). "Rogers, James Edwin Thorold". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 49. London: Smith, Elder & Co.