Josephine Nesbit | |

|---|---|

| Born | Josephine May Nesbit December 23, 1894 Butler, Missouri, US |

| Died | August 16, 1993 (aged 98) |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Josie Nesbit |

| Occupation | Army nurse |

Josephine May Nesbit (also known as Josie Nesbit;[1] December 23, 1894 – August 16, 1993) was an American nurse who served in the Army Nurse Corps.[2] She was second-in-command of the Angels of Bataan, Army nurses stationed in the Philippine Islands during World War II[2] who were the largest group of American women taken as prisoners of war.[3] Nesbit was noted for her "humane, dynamic leadership style."[2] She was credited with the survival of the nurses during the years they were held in captivity at Santo Tomas Internment Camp.[3][4]

Early life and education

Nesbit was born on her family's farm near Butler, Missouri on December 23, 1894.[2] She was the seventh of ten children and experienced a difficult early childhood.[4][5] As a child, she woke up before daylight to begin her chores and worked on the farm throughout the day.[6] By the time Nesbit was 12 years old, both her parents had died, leaving her and her siblings orphaned.[2][4][5][6] She first lived with her grandmother and later lived with a cousin in Kansas.[2][4]

She left high school at age 16.[4] After speaking with her sister's nursing superintendent, she chose to begin training as a nurse.[2] Seeking "adventure and independence," Nesbit became a registered nurse in 1914.[5]

Service in Army Nurse Corps

In 1918, an army recruiter visited Kansas City seeking nurses to help with the influenza pandemic, leading Nesbit to join the Army Nurse Corps.[2] She became Reserve Army Nurse N700 665 at Camp Logan Hospital in Houston, Texas on October 1, 1918.[2] Serving in the army reserve corps enabled Nesbit to travel and experience new adventures during peacetime.[6] She was able to hike the Rockies, visit Hawaii, and travel to Egypt's Valley of the Kings.[6]

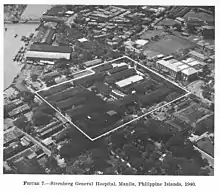

Sternberg General Hospital

Nesbit was on her second tour of duty in the Philippines when World War II began.[5] Until the war began, being stationed in the Philippines had been considered a "desirable posting," as there was plenty of free time, mild weather, and "luxurious accommodations."[5]

At Sternberg General Hospital in Manila, where she worked, Nesbit was a lieutenant and second in command to Captain Maude Davison, who was the chief nurse.[4] She was responsible for the nurses' work schedules.[4] While Davison was addressed as "Miss," Nesbit's staff referred to her as "Josie." Nesbit's Filipina colleagues referred to her as "Mama Josie."[2][4] She referred to her staff as "my girls."[2] Nesbit enjoyed socializing with her staff and was frequently consulted by them for advice on personal matters.[2]

In December 1941, Japan attacked the Philippines.[5] On December 8, 1941, Nesbit was the acting chief nurse at Stenberg General Hospital[1] as Davison had been injured in a night raid.[7] Since about 3:30 a.m., information about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had been reaching the nurses in Manila via radio; the American nurses stationed in the Philippines were concerned about their relatives and friends in Honolulu.[1] Nesbit told the staff, "Girls, you've got to sleep today. You can't weep and wail over this because you have to work tonight."[8] Less than nine hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese military bombed Baguio.[1] Fifteen minutes later, Clark Field was attacked; most of the American B-17 bombers were destroyed on the ground in the surprise attack.[1] Shortly thereafter, the hospital filled with patients.[1]

General Hospital #2 in Bataan

The Army Nurse Corps were ordered to set up a hospital in the jungle, General Hospital #2,[2] located along the Real River.[6] Without a building, the frontline hospital served 6,000 patients and had 18 wards.[5] Conditions were extremely rudimentary; patients lay on improvised cots and the jungle floor.[5] Many nurses cared for the patients while sick with malarial fever themselves.[5] Japanese soldiers were approaching and there was constant artillery fire.[5] Nesbit helped maintain "morale and solidarity," insisting that "the women respond always as nurses, as army officers and as a united group."[5] She took care of the nurses, commanding sick nurses to go to bed and locating shoes, clothing, and underwear for nurses who did not have them.[2] She convinced military pilots who were flying to outer Philippine islands to return with shoes and underwear for the nurses.[6] To provide privacy for the nurses, Nesbit located canvas field shelters issued by the military and used sheets of burlap to "section off a part of the jungle where the nurses slept."[6]

Corregidor

In April 1942, Japanese soldiers were less than two miles away.[5] Nesbit was informed by Colonel James E. Gillepsie, the medical commander, that only American nurses were to evacuate.[8] When told that the 26 Filipina nurses who had worked alongside the American nurses were to remain, she refused to leave unless all nurses were evacuated.[5] Gillepsie telephoned the headquarters and received permission to evacuate the Filipina nurses as well.[8] The nurses were then safely evacuated to Corregidor island in Manila Bay.[1][2] There, nurses worked in harsh conditions in an underground hospital located in Malinta Tunnel.[9]

On May 3, 1942, Nesbit and several other nurses were offered an opportunity to leave the island by evacuating on the last Allied submarine,[2] the USS Spearfish.[7] Along with Ann Mealor and Ann Wurts, she refused, volunteering to remain at the hospital[10] as she felt that her skills as a nurse were needed there.[2]

Internment at Santo Tomas Internment Camp

On May 6, 1942, Malinta Tunnel was captured by Japanese soldiers.[2] The nurses were taken prisoners of war and taken to Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Manila.[9] Disease and starvation were rampant in the camp and many nurses fell ill.[2] There, Nesbit and Maude Davison ran the camp hospital from August 1942 to February 1945.[2] For the next two years, Davison and Nesbit maintained the nurses' morale by establishing routines despite their imprisonment and requiring the nurses to work four-hour shifts every day.[9] If one of the nurses was too weak to complete her shift, Nesbit would often replace her personally.[5] She took care of the nurses, finding pieces of cloth for underwear and tiny pieces of meat to provide them with extra protein.[5]

In January 1945, Allied forces took over the Philippine Islands.[9] All the 3,700 prisoners of war[7] were liberated shortly thereafter, including the 77 nurses.[9] All of the nurses had survived, despite the challenges they had experienced.[9] Nesbit was credited with the survival of the nurses in captivity.[3][4]

Later life

After liberation, Nesbit returned to the United States.[2] She retired from the military on November 30, 1946, as a major with 28 years of service.[2] In June 1949, Nesbit married William Davis, a soldier who had also been interned in the war.[2] They lived a "quiet life" in California.[2]

In her later life, Nesbit continued to advocate for the nurses, writing to the Veterans Administration when she felt that their needs were not being met.[2] For 49 years, she sent cards and notes to every nurse who had served on her Philippine staff on Christmas and their birthdays.[2] In 1992, a ceremony was held in Washington D.C. celebrating the Angels of Bataan; Nesbit, at age 97, was unable to attend due to poor health but wrote a note for the dinner program explaining to her former staff that her "heart and spirit remained young" and that both were "big enough to still embrace her girls."[2]

Death

Nesbit died on August 16, 1993.[2] Her body was cremated and her ashes were scattered off the San Francisco coast.[2]

Honors and awards

- Bronze Star Medal, 1941–45[2]

- World War II Victory Medal, 1941–1945[2]

- American Defense Service Medal, 1941–45[2]

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, 1941–45[2]

- Distinguished Unit Badge, Presidential Unit Emblem with two Oak Leaf Clusters on Blue Ribbon, 1941–45[2]

- Philippine Defense Ribbon with one Bronze Service Star, 1941–45[2]

- Philippine Liberation Ribbon with one Bronze Service Star, 1941–45[2]

- American Campaign Medal and American Theater Ribbon, 1941–45[2]

- Philippine Independence Ribbon, 1941–45[2]

- Legion of Merit, 1941–42[2]

- World War I Victory Medal, 1918[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Manning, Michele. "U.S. Army War College - Strategic Studies Institute" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 Bullough, Vern L. (2000). American Nursing: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 3. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. pp. 215–218. ISBN 9780826111470.

- 1 2 3 Carter, Chelsea J. (April 7, 1999). "Bataan Nurses' Adventure Turned to Terror and WW II Prison Camp". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Norman, Elizabeth (1999). We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of the American Women Trapped on Bataan. Random House. ISBN 9780307799579.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Hanink, Elizabeth. "Josephine Nesbit and the WWII Angels of Bataan". Working Nurse. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Farrell, Mary Cronk (2014). Pure Grit: How American World War II Nurses Survived Battle and Prison Camp in the Pacific. Abrams. ISBN 9781613126370.

- 1 2 3 Tomblin, Barbara Brooks (2003). "War Comes to the Pacific". G.I. Nightingales: The Army Nurse Corps in World War II. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 13–37. ISBN 9780813190792.

- 1 2 3 Patrick, Bethanne Kelly. "Lt. Josephine Nesbit". www.military.com. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Angels of Bataan and Corregidor: 70 Years Later - History in the Headlines". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- ↑ "Philippine Defenders" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03.