Károly Kamermayer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mayor of Budapest | |

| In office 4 November 1873 – 25 November 1896 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | József Márkus |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 May 1829 Pest, Hungary |

| Died | 5 June 1897 (aged 68) Opatija (Abbazia), Austria-Hungary |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse | Klotild Sebastiani |

| Children | Irma Anna Alojzia |

| Profession | jurist, soldier |

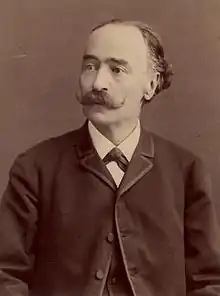

Károly Kamermayer (14 May 1829 – 5 June 1897) was a Hungarian jurist and councillor, who served as the first mayor of Budapest between 1873 and 1896. During his tenure, the city grew into the country's administrative, political, economic, trade, and cultural hub, and Budapest had become one of the cultural centers of Europe.

Early life

Also referred to as Kammermayer, he came from a bourgeois family of German origin, which had settled in Hungary in the 18th century. He was born in Pest on 14 May 1829, the son of wealthy industrialist József Kammermayer, who worked as operations manager at Count György Károlyi's glassworks in Parád.[1] His mother, Anna Emmerling, was a descendant of a patrician family in Pest.[1] Károly Kamermayer (who initially also wrote his name with double "m") finished his secondary studies in Gyöngyös. He attended the Archbishopric Lyceum of Eger, then studied law at the University of Pest (today Eötvös Loránd University, ELTE).[1]

Kamermayer began his political career as a deputy at the Diet of 1847–1848 during the Hungarian Reform Era. In early 1848, he was among Lajos Kossuth's so-called "parliamentary youth" (Hungarian: országgyűlési ifjak), the law students and junior clerks who supported the ideas of reform and progress represented by the liberal aristocracy at the Lower House of the Diet.[1] After the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, he joined as a volunteer in Colonel Lajos Kazinczy's sapper battalion.[2] He was later promoted to lieutenant in the 61st Battalion commanded by Major Pál Csuzy. He participated in the battles of Kápolna, Isaszeg, and others during the victorious spring campaign commanded by General Artúr Görgei in 1849. On 24 April 1849 he arrived in Pest with the engineer corps under the leadership of Colonel István Szekulics, which occupied and guarded the Chain Bridge. Kamermayer also fought in the Battle of Buda on 21 May 1849. He marched with Lajos Aulich to Komárom. The Imperial Russian Army attacked the Hungarian army on 20 June at Pered and on 28 June at Győr, winning both battles. At the end of the war, Kamermayer was promoted to first lieutenant by General György Klapka, who defended Komárom for two months even after the army's defeat.[1]

Early career

Following the defeat, he successfully avoided enforced military conscription to the Austrian Imperial Army. He returned to Pest to finish his interrupted legal studies. Having done so he began to work as an inspector in the city jail.[1] In 1857 he took part in the management of the census process for a daily wage, then became a secretary. After the adoption of the October Diploma in 1860, he was elected to the General Assembly of Buda along with several other 1848 veterans and re-entrant officials. On 1 February 1861, he was appointed the chief notary of Buda. He gave a memorable speech on the occasion of the one-year anniversary of the suicide of Count István Széchenyi in April 1861, demanding the revival of the 1848 revolution's constitutional spirit. The speech brought him widespread national and political acclaim.[3] After the dissolution of the Diet of 1861, and the suspension of the local government system by Emperor-King Francis Joseph I's absolutist regime, the entire General Assembly, including Kamermayer, resigned in protest on 31 October 1861. However, he was appointed councillor on 24 November, because of his expertise and apolitical professional attitude.[4]

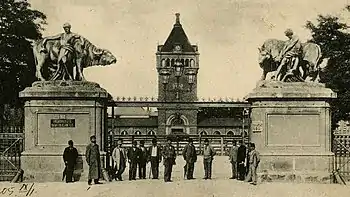

After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, he was elected councillor in the Pest assembly on 19 May 1867. In that capacity, he was responsible for public health, animal health, and public sanitation issues, and also oversaw the operation of business associations, guilds, and the city tax office. On 1 August 1872, he played a major role in the establishment of the Central City Communal Slaughterhouse (Hungarian: Közvágóhíd).[5] The structure was preceded by years of preparation. A delegation led by Kamermayer made study visits to several cities, including: Berlin, Dresden, Munich, Frankfurt, Prague, and Vienna. He studied their facilities before making the necessary improvements and reforms in Pest. His political creed had become that of catching up to Western urban living standards. To achieve this he was convinced that the most important first step was the creation and centralized management of a public sanitation system.[6] The communal slaughterhouse building complex was planned by architect Hermann von der Hude and built by Gyula Hennicker. It contained thirty cutting chambers, indoor courtyards, leather drying attics, underground cooling chambers, a self-contained sewerage system, and a separate cattle market which was suitable for accommodating five thousand livestock and tens of thousands of poultry. Kamermayer personally wrote a draft of the communal sanitation regulations.[6]

Mayor of Budapest

Election and administration

After the municipal election held on 25–26 September 1873, the newly elected 400-member General Assembly of Budapest held its inaugural session on 25 October 1873, as a major step in the process of establishing Budapest by unifying Buda and Óbuda on the west bank of the river Danube, with Pest on its east bank.[7] The assembly elected the first Lord Mayor among the three candidates nominated by countersignature of King Francis Joseph I after consultations with the Ministry of Interior.[8]

On 30 October 1873, four candidates, including Kamermayer, were selected by an election commission headed by Lord Mayor Károly Ráth for the position of Mayor. According to the city unification law (Statute XXXVI of 1872), the Mayor of Budapest was head of the local government, while the Lord Mayor became a representative on the executive branch of the government thus establishing a two-tier local government system in Budapest.[9] On 4 November 1873, Károly Kamermayer was elected the first Mayor of Budapest, obtaining 297 of 348 votes.[9] According to the contemporary press, Kamermayer's "unpretentious and diligent habit, conscientious sense of duty and tireless perseverance" made him well suited to fill the office.[10] The next day, Károly Gerlóczy and the elderly Mihály Kada were elected his first and second deputies, respectively, and all councillors took their offices by November 11. Budapest officially became a single city on 17 November 1873, when the General Assembly took over the responsibilities of the discontinued city councils.[11]

As the contemporary press and politicians noted, Budapest came under the rule of the three Károlys: Lord Mayor Ráth, Mayor Kamermayer, and Deputy Mayor Gerlóczy, who remained in office over the next two decades.[12] Between them, a close professional and collegial relationship had developed. In the early years, in addition to the promoters' voices, there were serious concerns regarding the benefits of the unification.[13] For instance, Móric Szentkirályi, who formerly served as the last Lord Mayor of Pest (1867–1868), argued that "Buda generally has no future" which can only be a burden for the industrializing and growing Pest. He added that Buda is "not a Hungarian town", referring to the large number of German-speaking residents. Scholar József Göőz also argued that during severe winters the two main parts of Budapest were almost completely isolated from each other, and he also emphasized their continuing persistent self-interest.[13] Journalist Péter Buza compared the city's unification to a marriage: "[...] there is no real trust between each other. What kind of marriage is this? No doubt, like all other similar cases. One party is forcing its will on the other."[14] However these skeptical voices were in the minority. For the coming years, a new "Budapest elite" emerged, overcoming the old urban political voting blocks. Both Ráth and Kamermayer were members of the so-called "Eagles", an influential intellectual group, which permanently convened at the Arany Sas Fogadó (lit. Golden Eagle Inn). It acted as a lobbying group, determining the city's policy orientations and objectives.[15] During these gatherings, Kamermayer was famous for his taste in refined gastronomy. The Kamermayer torte, also known as Kamermayer's Joy (Hungarian: Kamermayer öröme) was named after him.[2]

In his inaugural speech after taking the oath, Kamermayer emphasized the importance of the principles of thrift and the need to establish national unity in Budapest. He also underlined that, in addition to adoption of a frugal budget, the creation of the preconditions for the population's comfort requirements was also priority. His infrastructure investment aims, such as the construction of a modern sewerage system, and the establishment of new market halls, also served his public health efforts. However the local authority had only limited financial opportunities in that regard, though Kamermayer could use his informal influence at the national parliament.[10] During the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, the mayor was an administrative rather than a political position, as the law on classification of civil servants (Statute I of 1883) required the office-holder be a legal and political science graduate. A lot of the administration was concentrated in Kamermayer's hands, for example: civil registration of births, marriages, citizenship naturalization, and the authorisation of water management. As a result, during this period Budapest's administrative system was often called "water-headed".[16] Journalist and councillor Ambrus Neményi (uncle of mathematician Paul Neményi) pointed out the negative effects of the city's bureaucracy during the budget negotiations of 1886; he said the city administration lacked a sense of initiative and managed only routine duties. In response, Gerlóczy referred to the limited margin for maneuver laid down by administrative law.[17] However, from a different angle, Kamermayer had much greater autonomy than mayors of towns in the countryside. Károly Ráth, as lord mayor, had much less jurisdiction than Ispáns (or Lord Lieutenants) of the counties because of the restrictions on who could vote. This allowed the upper middle class and the elite senior administrative bureaucracy in Budapest wide room to maneuver.[18]

Nevertheless, Kamermayer had to raise numerous jurisdictional conflicts with the national cabinet during the governance of the powerful and charismatic Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza (1875–1890). He argued that several elements of the administrative law were inapplicable to Budapest's conditions. Above all, every document issued by the local government council had to be signed by Kamermayer himself which made the smooth flow of administration difficult. The Mayor tried unsuccessfully to initiate amendments to the law over the decades. Kamermayer and his colleagues also criticized the government's intent to diminish the city's autonomy. In other cases, the General Assembly was forced to take on government duties, which resulted in an increase in budget expenditures.[19]

Depression of 1873–79

Kamermayer successfully ensured that Hungarian entrepreneurs from Budapest and elsewhere were able to exhibit their products (for instance, Hungary's first steam locomotive by MÁVAG and ceramic works by Zsolnay Porcelain Manufacture) at the 1873 World's Fair in Vienna.[10] He also initiated a visit to Budapest by the world exposition's international jury.[2] As a result, Kamermayer was given the title of royal counselor by Francis Joseph on 8 December 1873.[10] In 1875, 1876, and 1878 large storms coming from the Transdanubian region arrived in Central Hungary damaging several areas in Budapest. In the winter of 1876, icy flood waters swept away buildings and parts of the low wharves of Buda and Óbuda. Pest survived unharmed by the flood because of its existing drainage system. During the emergency, Kamermayer demonstrated his organizational and management abilities and in recognition of this was awarded the Order of the Iron Crown 3rd Class. He gave protection to refugees following the Occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878, and also organized fundraising for the victims of the 1879 Great Flood in Szeged for which he received royal acknowledgment from Francis Joseph.[20]

The city administration had to face a number of difficult problems beside natural disasters and floods in the first period. By 1873–74, the sewerage system in Pest, designed by British engineer William Lindley in late 1860s, proved to be a flawed professional decision. The temporary waterworks, established in 1868, delivered mixed, artificially filtered and unfiltered water which caused a deterioration in the quality of potable water resulting in several public health threats. Supply interruptions also occurred on a permanent basis. The 1872–73 cholera epidemic clearly showed the system's deficiencies and weaknesses. Even Lindley suggested the establishment of an advanced and permanent waterworks.[21] However the Panic of 1873, followed by the so-called Long Depression, did not yet allow that kind of substantial investment. During Kamermayer's first mayoral term (1873–1879), only frugal budgets were adopted. During that period, investment spending decreased from 32 (1874) to 12 percent (1879), compared to the rate of ordinary revenues.[22]

Notwithstanding the reduction in spending, numerous significant investments were made during Kamermayer's first mayoral term (though, many of them were initiated and launched before the unification). The first People's Theatre (Hungarian: Népszínház), constructed by Fellner & Helmer, opened its doors on 15 October 1875, the opening ceremony was also attended by Francis Joseph and his son, Crown Prince Rudolph. The city administration collected the expenditures through donations and aid. Kamermayer emphasized the development of Hungarian as the national language and its spread among Budapest's bourgeoisie many of whom were still of German origin. The Music Academy was founded on 14 November 1875. By 1879, the academy relocated to a three-story Neo-Renaissance building designed by Adolf Láng built on today's Andrássy Avenue.[23] The Budapest Cog-wheel Railway was put into operation on 24 June 1874, the whole line was built according to Riggenbach's cog-wheel system.[24] In the same year, the New City Hall was built on Váci Street, which today is the seat of the General Assembly (while the Old City Hall building near Deák Ferenc Square in Városház Street, remained the office of Budapest's Mayor).[25] The Margaret Bridge was built by the Ernest Goüin et Cie. construction company between 1872 and 1876 becoming the second permanent bridge in Budapest after the Chain Bridge.[26] The Nyugati Railway Terminal, built by the Eiffel Company, was opened on 28 October 1877. (The Ferdinand Bridge, which connected Terézváros and Újlipótváros neighborhoods over the railway lines, was already completed in 1874).[26]

Social affairs were conducted through the lens of the importance of sanitation. Therefore, the Kamermayer administration treated the issue of homelessness as a matter of law enforcement. The ordinance of poverty regulation, issued by the General Assembly in 1875, also reflected this attitude resulting in many homeless people being deported from the city centre.[20] The annual budgets marginally addressed the problem of individual aid systems, however numerous social institutions were created over the years. The communal poorhouse was expanded, and several free public baths were established. New correctional facilities were also built. The small number of hospitals was a serious problem, and they often struggled with overcrowding. There was no solution forthcoming for this. In 1876, the Saint Roch Hospital was extended with new buildings, while the first psychiatric institution (Hungarian: Első Magyar Hülyenevelő és Ápoló Intézet) opened in 1877.[27]

Infrastructure and sanitation

Following the municipal election held on 19 September 1879, Kamermayer was re-elected Mayor of Budapest for another six-year term.[28] After the end of the Long Depression, the General Assembly was able to adopt a more ambitious budget, which included a proposal to borrow 20 million forint. With this amount, the city administration intended to finance its educational and public utility investment programs. Initially, it received a loan of only 6 million forint from foreign banks.[27] As a result, the General Assembly began to implement the plan for a new modern sewerage system. While the Public Works Council supported the principle of artificial water filtration, Kamermayer and his colleagues opted for a system of natural filtering.[20] Under the direction of chief architect Lajos Lechner and mining engineer János Wein, the first permanent waterworks was built in Budaújlak in 1881, which still operates today as the oldest such facility in Budapest. Initially, the waterworks produced 21,000 m³ of water, ensuring the supply of Buda and Óbuda. Later, through water conduit pipes added to the Margaret Bridge, Pest has also benefited from the production of drinking water. Later, between 1893 and 1904, another waterworks was built in Káposztásmegyer (today part of Újpest), completing the water network throughout the city.[29]

Between 1880 and 1883, several warehouses were established in the city suitable for the storage of 50 thousand tons of grain. Consequently, this investment boosted the local grain trade, and contributed significantly to the growth of Budapest as a centre of the milling industry. With the rental of these warehouses, and the tax revenues, the city avoided long-term indebtedness, even after borrowing large amounts of money.[27] A bucket elevator ("Elevátor") was also built in 1881 in the Boráros Square (today in Ferencváros), which functioned until World War II. Despite the fact that it was an urban project, the city administration leased the Elevator to the Hungarian Exchange Bank for sixty years.[30]

The most grandiose project in the 1880s was the construction of Andrássy Avenue ("The Aristocrat of the Roads"), which links the inner city areas with the City Park, and was designed to reduce the heavy traffic on Király Street which ran parallel to it. It was decreed to be built in 1870, and its construction began in 1872.[23] The first phase of the avenue was already inaugurated on 20 August 1876. Along the avenue palaces, financed by Hungarian and other banking houses, were built by the most distinguished architects of the time, led by Miklós Ybl. These were largely finished by 1884 and mostly aristocrats, bankers, landowners, and old established families moved in. In 1885, the road was named after the main supporter of the plan Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy.[23] Connecting to that project, a new railway terminal (Budapest Keleti railway station) was also constructed between 1881 and 1884 as one of the most modern European railway stations.[31]

Another project was the development of the Grand Boulevard. After rejecting Ferenc Reitter's original plan for the construction of navigable channels, the city administration designated the boulevard's route from the Margaret Bridge to the Üllői Street.[23] The first phase lasted from 1872 to 1883 with minimal construction occurring because of the economic crisis of 1873. During this time only twenty-three public facilities were built along the boulevard, including the above-mentioned People's Theatre and Nyugati Railway Terminal. At the time of Kamermayer's second mayoral term, the government and the city administration accelerated the work. Between 1884 and 1890, 106 buildings were constructed and the route between Váci Avenue and Király Street was almost completely rebuilt with several municipal flats, iron factories, tanning-yards, and clothes factories. The third phase was launched in 1891, during Kamermayer's last term, and continued until the 1896 millennium celebrations. The New York Palace, the Comedy Theatre, and the Royal Hotel were built during this period.[32]

Kamermayer, who intended to run for a third mayoral term, faced a harsh and tough battle during the 1885 municipal election. In the city centre a rival bloc, supported by the Tisza government, ran in the election against the "Eagles" which was open towards the parliamentary opposition, especially the Party of Independence and '48.[33] According to a journalist of the pro-government Pesti Hírlap, "a tight inner circle has built up autocracy on the city's affairs". Despite the sharp words, Kamermayer and the "Eagles" won a convincing majority in the city centre. In Józsefváros, the "Eagles" main opponent was the allegedly anti-Semitic "White Horse" group whose numbers grew following the Tiszaeszlár blood libel.[34]

The first electric tram system, introduced on 28 November 1887, ran between Nyugati Railway Terminal and Király Street.[35] The track gauge of this first line was 1,000 mm (39 in) and electricity was supplied to the cars from below to avoid cables hanging across the street. On 20 July 1889, the second line, which spanned from Egyetem Square to Fiumei Road via Kálvin Square, was opened. It was designed so that in case of a power failure steam engines could tow the carriages. The third line, also standard gauge, was opened on 10 September 1889, and ran from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA) to Andrássy Avenue.[35]

Based on previous enhancements, the New Hospital (after 1894, Saint Stephen Hospital), designed by Alajos Hauszmann, was established on 5 August 1885 in the Üllői Street and became the most prominent health investment of the Kamermayer era. The hospital, which had a pavilion structure, opened its doors with eight departments and 656 beds. Kamermayer also decreed that epidemiological measures had to be taken including, among other things: compulsory notification and isolation of infectious diseases, and the institutional organization of disinfection by the health authorities. During the National Exhibition of 1885 regular waste removal began and the first horse-drawn sweeping machines appeared on the streets of Budapest.[27] The Public Food and Supply Department was also established in 1885. Its most important task was the organization of the market halls' system begun in the 1890s. The Kamermayer administration also founded a new orphanage and a municipal hospice, while several soup-kitchens were established in working-class neighborhoods.[27]

Last years

His fourth and last mayoral term began after the 1891 municipal election, which was accompanied by violent struggles due to political instability after the fall and resignation of Kálmán Tisza.[34] Kamermayer played a significant role in the establishment of a new administrative structure in Budapest in 1893, increasing the importance of district offices (called prefectures at the time). He considered the development of district administrations as indispensable, reducing the overloading of the "water-headed"-type central city management. Accordingly, local public health, technical infrastructure, and public service agencies were established by district. Consequently, the prefects of the districts became authorities of first instance in city affairs. However, Kamermayer and his staff, who represented the concept of a unified city, rejected the idea that the prefects should be elected by their local assemblies, fearing the danger of constant fragmentation. Thus the prefect was appointed by the General Assembly.[36]

Kamermayer's greatest personal success was the development of a network of market halls in the 1890s. Along with his successor József Márkus, he had described his idea in May 1882, releasing a report titled Memoir Concerning the Market Halls. Kamermayer stressed the importance of permanent and reliable markets, which were able to serve the needs of the rapidly growing population. In his work, Kamermayer cited examples primarily from London and Paris.[36] The most impressive market was the Great Market Hall, the largest and oldest indoor market in Budapest. Designed and built by Samu Pecz in 1897, it is located at the end of the Váci Street on the Pest side of the Liberty Bridge (completed in 1896) at Fővám Square.[17]

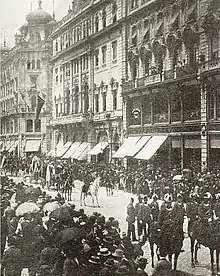

Kamermayer led Budapest as a non-partisan and apolitical manager. However, it was known that he sympathized with the opposition which represented the '48 ideology and rejected the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. There was a striking manifestation of this. When Lajos Kossuth turned 90, at Kamermayer's initiative, he was awarded honorary citizenship of Budapest by the General Assembly on 14 September 1892. The Mayor personally led a delegation to Turin, Italy, where Kossuth spent his last years in exile, to hand over the certificate of honorary citizenship to his old mentor and idol.[37] Following Kossuth's death on 20 March 1894, Kamermayer supported the government in a politically sensitive case. Kossuth's body was brought to Budapest, where he was buried in the Kerepesi Cemetery following a large ceremonial funeral procession on 1 April 1894. Out of respect for Francis Joseph and his Austrian counterpart, the Hungarian cabinet did not have an official representative at the event. Kamermayer also had to stay away from the funeral. Budapest was represented by Deputy Mayor Gerlóczy, who also made a speech.[37]

The crowning achievement of his 23-year term was the 1896 millennium celebrations, lasting from 2 May to 31 October, commemorating the anniversary of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin. Organized by the Hungarian state, the City Park was the main venue for the events. The celebrations became the symbol of the Golden Age of Budapest, which corresponded with Kamermayer's terms as mayor.[29] Within the project, the construction on the first metro line began in 1894. Completed by the deadline, it was inaugurated on 2 May 1896 by Francis Joseph. It is the second oldest underground railway in the world (the first being the London Underground), and was the first on the European mainland.[29]

Retirement and death

During the last years of his mayoral term, Kamermayer's health deteriorated. Moreover, he faced increasingly harsher resistance in the General Assembly as Hungarian national politics became cloudy during the premiership of Dezső Bánffy. In November 1895, his draft in connection with the market halls construction project was outvoted following a motion by fellow councillor Ferenc Heltai. Kamermayer was on sick leave more and more frequently in the following months. In October 1896, he announced his retirement and that he did not intend to participate in the upcoming municipal election of 1897. The General Assembly made Kamermayer an honorary citizen of Budapest on 4 November 1896. He was replaced by József Márkus on 25 November 1896.[17]

His personal prestige project, the Great Market Hall was completed just after his retirement, and Kamermayer participated in the opening ceremony as an ordinary citizen. His illness progressed to an advanced stage. He left for medical treatment at Abbazia (today Opatija, Croatia), where he died on 5 June 1897, six months after his resignation. He was buried in the Kerepesi Cemetery following a solemn funeral procession. His headstone was designed by sculptor Gyula Donáth.[17] His colleague and close ally, Lord Mayor Károly Ráth passed away less than two months later, on 30 July 1897. Deputy Mayor Károly Gerlóczy ran unsuccessfully for the position of Mayor following Kamermayer's resignation. As a result, he too retired at the end of 1897, thereby completely passing the city administration to a new generation.[38]

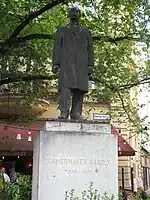

Kamermayer married Klotild Sebastiani de Remete et Pogányest (1839–1911) on 13 July 1863. His wife came from a wealthy bourgeoisie family of Italian and Greek origin, which was granted nobility before 1848. They had two daughters, Irma (born 1866) and Anna Alojzia (born 1870).[39] Kamermayer's great-great-great-grandson is politician Antal Csárdi (LMP), who was candidate for the position of Mayor of Budapest in the 2014 municipal election. A small square was named after Kamermayer in Lipótváros, in front of the Gerlóczy Café, where a life-size statue, conceived by sculptor Béla Szabados, was erected in 1942.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Horváth J. 2008, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 Draveczky 1998, p. 48.

- ↑ Horváth J. 2008, p. 140.

- ↑ Horváth J. 2008, p. 141.

- ↑ Horváth J. 2008, p. 142.

- 1 2 Horváth J. 2008, p. 143.

- ↑ Horváth J. 2010, p. 16.

- ↑ Sipos 2008, p. 11.

- 1 2 Sipos 2008, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 Horváth J. 2008, p. 146.

- ↑ Vörös 1978, p. 314.

- ↑ Katona 2010, p. 50.

- 1 2 Katona 2010, p. 51.

- ↑ Katona 2010, p. 52.

- 1 2 Draveczky 1998, p. 47.

- ↑ Sipos 2008, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Horváth J. 2008, p. 152.

- ↑ Sipos 2008, p. 21.

- ↑ Horváth J. 2008, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 Horváth J. 2008, p. 149.

- ↑ Vörös 1978, p. 205.

- ↑ Horváth J. 2008, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 4 Vörös 1978, p. 456.

- ↑ Vörös 1978, p. 206.

- ↑ Vörös 1978, p. 260.

- 1 2 Vörös 1978, p. 306.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Horváth J. 2008, p. 150.

- ↑ Horváth J. 2010, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Vörös 1978, p. 403.

- ↑ Vörös 1978, p. 334.

- ↑ Vörös 1978, p. 326.

- ↑ Vörös 1978, p. 606.

- ↑ Horváth J. 2010, p. 25.

- 1 2 Horváth J. 2010, p. 26.

- 1 2 Vörös 1978, p. 407.

- 1 2 Horváth J. 2008, p. 151.

- 1 2 Vörös 1978, p. 464.

- ↑ Vörös 1978, p. 473.

- ↑ Vörös 1978, p. 426.

Sources

- Draveczky, Balázs (1998). "A "Sasok" és Kamermayer Károly". Tanulmányok Budapest Múltjából 27. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 45–51.

- Horváth J., András (2008). "Kamermayer Károly". In Feitl, István (ed.). A főváros élén. Budapest főpolgármesterei és polgármesterei, 1873–1950 [=At the Helm of the Capital: Lord Mayors and Mayors of Budapest, 1873–1950] (in Hungarian). Napvilág Kiadó. pp. 139–153. ISBN 978-963-9697-19-5.

- Horváth J., András (2010). "Önkormányzati képviselő-választások, 1867–1912". In Feitl, István; Ignácz, Károly (eds.). Önkormányzati választások Budapesten, 1867–2010 [=Municipal Elections in Budapest, 1867–2010] (in Hungarian). Napvilág Kiadó. pp. 13–55. ISBN 978-963-9697-79-9.

- Katona, Csaba (2010). "A főpolgármester és a polgármester: amikor Ráth Károly és Kamermayer Károly Budapest élére került". Győri Tanulmányok. Győr: Local Government of Győr. 30: 47–55. ISSN 0209-4215.

- Sipos, András (2008). ""Dualizmus" a főváros élén. A főpolgármesteri és a polgármesteri intézmény, 1873–1950". In Feitl, István (ed.). A főváros élén. Budapest főpolgármesterei és polgármesterei, 1873–1950 [=At the Helm of the Capital: Lord Mayors and Mayors of Budapest, 1873–1950] (in Hungarian). Napvilág Kiadó. pp. 11–26. ISBN 978-963-9697-19-5.

- Vörös, Károly, ed. (1978). Budapest története IV. A márciusi forradalomtól az őszirózsás forradalomig [=History of Budapest IV.: From the March Revolution to the Aster Revolution] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-1083-9.