The Kaisariani Monastery (Greek: Μονή Καισαριανής) is an Eastern Orthodox monastery built on the north side of Mount Hymettus, near Athens, Greece.

History

The monastery was probably established in Byzantine times in ca. 1100, which is the date of construction of the surviving church (the monastery's katholikon). Nevertheless, the site has a far longer history as a cult center: in Antiquity, it was probably a site dedicated to Aphrodite, before being taken over by Christians in the 5th/6th centuries. Remains of a large early Christian basilica lie to the west, over which a smaller church was built in the 10th/11th centuries.[1]

The monastery is mentioned by Pope Innocent III after the Fourth Crusade, but seems to have remained in Greek Orthodox hands, unlike other churches and monasteries that were taken over by Latin (Roman Catholic) clergy. A further, now ruined single-aisled church, was built to the southwest during the Frankish period.[1] When, in 1458, the Turks occupied Attica, Sultan Mehmed II went to the monastery and, according to Jacob Spon (1675), a French doctor from Lyon, that is where he was given the key to the city.

In 1678, Patriarch Dionysius IV of Constantinople defined the monastery as Stauropegic, that is to say, free and independent of the metropolitan bishop: its only obligation was to perform funeral rites. Later on, in 1792, Patriarch Neophytos VII of Constantinople retracted the monastery's privileges; it once again came under the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan of Athens. From 1824 onwards, the monastery was "submitted to abject treatment. What had previously been instrumental in enlightening mankind and saving souls, was now being used as a palace for cows, fowl and horses".

During its apogee, it had hosted many significant spiritual figures of the time, such as Theophanis in 1566 and Ioannis Doriano in 1675, the Abbot Izekel Stephanaki, who was knowledgeable in Greek literature and history, and more particularly, Platonic philosophy. From 1722 until 1728, Theophanis Kavallaris taught courses in grammar and sciences there.

Kaisariani Monastery's library was renowned and most probably owned documents from antiquity's libraries. According to the demogerontes (the council of elders) of the time, "the manuscripts were sold to the English as membranes whereas the rest of the documents were used in the metropolis` kitchens." During the Turkish siege of the Acropolis (1826–1827), the manuscripts were transported to the Acropolis of Athens and were used to ignite fuses.

The fertile surrounding lands belonged to the monastery, as did various other holdings, such as St. John the Baptist, next to the Kaisariani road or those in Anavyssos.

The monks' income was substantiated by the produce from their olive groves, grape vines and beehives. In a letter, dated 1209, Michael Hionati reports that "the produce from the beehives was given to the Hegumen of Kaisariani Monastery. However, four years later, he complains about not having received any income from the monastery: the Abbot gave, as an excuse that the beehives had been destroyed. The monks were also renowned for concocting medicine from various herbs.

The monuments

A high wall surrounds the buildings, the catholicon (main church), the refectory, the bathhouse and the cells, so that, even today, they seem quite well protected. In its original design, there were two entrances, the main entrance on the eastern side and a larger one on the other side.

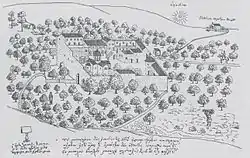

The monastery was built on the ruins of a lay building. The drawing of Kaisariani Monastery, done in 1745 by a Russian pilgrim named Barski, depicts the following buildings: the catholicon on the eastern side of the wall around the abbey, the bathhouse on the south side and, bordering it, the monks' cells with the Benizelou tower and the refectory in the western wing. Beside the vegetable garden on the southwestern side of the monastery, you can see the monks' cemetery and a newer church.

The katholikon is of the usual Byzantine cross-in-square type, with half-hexagonal apses. The narthex and frescoes of the katholikon, however, date to Ottoman times, as do most of the other buildings of the monastery, with the exception of the olive oil press, originally a bath, which appears to be contemporary with the katholikon.[1] The buildings are all disposed around a courtyard. The catholicon was on the eastern side, the refectory and the kitchen, on the western side and the bathhouse, which was transformed into the monastery's olive oil extractor during the Turkish rule, and, finally, the monks' cells in front of which there was an open arcade.

The catholicon is dedicated to the Presentation of the Theotokos in the Temple and had the basic cross shape, faithful to Greek tradition, according to M. Sotiriou, or the semicircular quadripartite according to Anastassios Orlandos.

The entrance of the temple was located on its western side without being separated by a narthex. There was another entrance on the northern side: with a marble doorstep and a Roman architrave. The narthex, which was surely built before 1602, is a vaulted ceiling with a cupola and lunette in the middle.

The frescoes

The oldest fresco is located on the external southern wall of the catholicon that now includes St. Anthony's chapel. It is of the Theotokos, turned to the left in prayer. Its sweeping brushstrokes suggest a 14th-century rural technique.

The church and its narthex are decorated with frescoes, dating from the Ottoman period. The wealthy Benizelos family subsidized the frescoes, painted in 1682 by Ioannis Ypatos, from the Peloponnese, according to the inscription on the western wall. The cupola represents Christ Pantokrator. On the bi-partite rosette, are depicted: the Preparation of the Throne, the Virgin, John the Forerunner, the angels and a composite fresco of the Four Evangelists are represented. On the chapel's lunette, the Virgin Platytera enthroned, with angels seated on either side.

Although the frescoes do not distinguish themselves with any innovations in fresco technique, they nonetheless remain prototypes of the 16th-century frescoes found in the Mount Athos. During the 17th century, frescoes became more and more popular in style and technique.

The bath house

Kaisariani's bath house, along with those that have been salvaged in Daphni Monastery and Dervenosalesi of Cithaeron, are examples of 11th-century architecture which confirm the belief that monks often used bath houses. Warm water was used for heating the cells, the refectory, etc.

The buildings located on the left of the eastern entrance, across from the south side of the catholicon encircle a natural source. It is covered by a semi-spherical unvaulted cupola, which is supported by four pendentives. These small pendentives, which support the protective roof, have been destroyed because, as we have previously mentioned, it was transformed into an olive press. The jars, which have been preserved, testify to this transformation.

The great earthquake of 1981 caused serious damage to parts of the monastery complex, particularly to the bath house and refectory. Eleven years later, the Minister of Cultural Affairs appointed the Philodasiki Enosi Athinon, a Greek NGO, to administer the restoration of the bath house under the supervision of the First Byzantine and Meta-Byzantine Archeological Service. Before the restoration could be completed, the 1999 earthquake once again interrupted the works, this time for many years.

A later Minister of Cultural Affairs assigned the implementation of a new study, drafted by the Directory of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Monuments of the Ministry of Cultural Affairs to the Philodasiki inasmuch as they would also assume complete financial responsibility for the works. The works were nonetheless resumed, to be again interrupted, indefinitely this time, for technical reasons that had nothing to do with the Philodassiki itself.

The refectory

The refectory and the kitchen are located in an independent building on the western side of the wall, across from the catholicon. The refectory is a long rectangular shaped vaulted room, which is subdivided into two spaces. The kitchen on the south side of the refectory is square shaped with a vaulted roof in which there is a chimney. The hearth is in the middle of the room, surrounded by a step, built at the foot of its four walls. The building probably dates from the 16th or 17th century.

The monks' cells, along with Benizelou's tower, occupy nearly the whole southern length of the garden.

In cooperation with the Archeological Service, the Philodasiki restored the complex of the Holy Monastery of Kaisariani between 1952-1955; the association supervised and funded all of the works. Tassos Margaritof restored the post-Byzantine icons it contained.

References

- 1 2 3 Gregory, Timothy E. (1991). "Kaisariane". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1090. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.