| Charlemagne | |

|---|---|

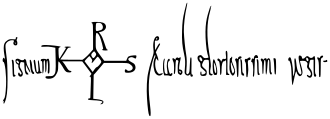

A denarius of Charlemagne dated c. 812–814 with the inscription KAROLVS IMP AVG (Karolus Imperator Augustus) | |

| King of the Franks | |

| Reign | 9 October 768 – 28 January 814 |

| Coronation | 9 October 768 Noyon |

| Predecessor | Pepin the Short |

| Successor | Louis the Pious |

| King of the Lombards | |

| Reign | 10 July 774 – 28 January 814 |

| Coronation | 10 July 774 Pavia |

| Predecessor | Desiderius |

| Successor | Bernard |

| Emperor of the Carolingian Empire | |

| Reign | 25 December 800 – 28 January 814 |

| Coronation | 25 December 800 Old St. Peter's Basilica, Rome |

| Successor | Louis the Pious |

| Born | 2 April 748[lower-alpha 1] |

| Died | 28 January 814 Aachen, Francia |

| Burial | |

| Spouses |

|

| Issue Among others | |

| Dynasty | Carolingian |

| Father | Pepin the Short |

| Mother | Bertrada of Laon |

| Religion | Chalcedonian Christianity |

| Signum manus | |

| Carolingian dynasty |

|---|

|

Charlemagne[lower-alpha 2] (/ˈʃɑːrləmeɪn, ˌʃɑːrləˈmeɪn/ SHAR-lə-mayn, -MAYN; 2 April 748[lower-alpha 1] – 28 January 814) was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and Emperor from 800, all until his death. Charlemagne succeeded in uniting the majority of Western and Central Europe, and he was the first recognized emperor to rule Western Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire approximately three centuries earlier. Charlemagne's rule saw a program of political and societal changes that had a lasting impact on Europe in the Middle Ages.

A member of the Frankish Carolingian dynasty, Charlemagne was the eldest son of Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon. With his brother Carloman I, he became king of the Franks in 768 following Pepins's death, and became sole ruler in 771. As king, he continued his father's policy towards the protection of the papacy and became its chief defender, removing the Lombards from power in northern Italy in 774. Charlemagne's reign saw a period of expansion that led to conquests of Bavaria, Saxony, and northern Spain, as well as other campaigns that led Charles to extend his rule over a vast area of Europe. He spread Christianity to his new conquests, often by force, as seen at the Massacre of Verden against the Saxons.

In 800, Charlemagne was crowned as emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III. While historians debate about the exact significance of the coronation, the title represented the height of prestige and authority he had achieved. Charlemagne's position as the first emperor in the West in over 300 years brought him into conflict with the contemporary Eastern Roman Empire based in Constantinople. As king and emperor, Charlemagne engaged in a series of reforms in administration, law, education, military organization, and religion which shaped Europe for centuries. The stability of his reign saw the beginning of a period of significant cultural activity known as the Carolingian Renaissance.

Charlemagne died in 814, and was laid to rest in the Aachen Cathedral, in his imperial capital city of Aachen. He was succeeded by his only surviving son Louis the Pious. After Louis, the Frankish kingdom would be divided, eventually coalescing into West and East Francia, which would respectively become France and the Holy Roman Empire. Charlemagne's profound impact on the Middle Ages, and the influence on the vast territory he ruled has led him to be called the "Father of Europe". He is seen as a founding figure by multiple European states, and many historical royal houses of Europe trace their lineage back to him. Charlemagne has been the subject of artwork, monuments, and literature since the medieval period, and has received veneration in the Catholic Church.

Name

Various languages were spoken in Charlemagne's world, and he would have been known to contemporaries as: Karlus in the Germanic dialect he spoke; Karlo to Romance speakers; or Carolus (or an alternative form, Karolus)[2] in Latin, the formal language of writing and diplomacy.[3] Charles is the modern English form of these names.

The name Charlemagne, by which the emperor is normally known in English, comes from the French Charles-le-magne, meaning "Charles the Great". In modern German, he is known as Karl der Große. The nickname magnus (great) may have been associated with him already in his lifetime, but this is not certain. The contemporary Latin Royal Frankish Annals routinely call him Carolus magnus rex, "Charles the great king".[4] As a nickname, it is certainly attested in the works of the Poeta Saxo around 900 and it only became standard in all the lands of his former empire around 1000.[5]

Charles's achievements gave a new meaning to his name. In many Slavic, Baltic and Turkic languages, the very word for "king" derives from his name; e.g., Polish: król, Ukrainian: король (korol'), Czech: král, Slovak: kráľ, Lithuanian: karalius, Latvian: karalis, Russian: король, Macedonian: крал, Bulgarian: крал, Serbo-Croatian: краљ/kralj, Turkish: kral. This development parallels that of the name of the Caesars in the original Roman Empire, which became kaiser and tsar (or czar), among others.[6][7]

Early life and rise to power

Political background and ancestry

By the 6th century, the western Germanic tribe of the Franks had been Christianised, due in considerable measure to the Catholic conversion of Clovis I.[8] Francia, ruled by the Merovingians, was the most powerful of the kingdoms that succeeded the Western Roman Empire,[9] encompassing nearly all of modern France and Switzerland, along with parts of modern Germany and the Low Countries.[10] Francia was often divided in several sub-kingdoms under different Merovingian kings, due to ill-defined succession laws.[11] The late 7th century saw a period of war and instability following the murder of King Childeric II, which led to factional struggles among the Frankish aristocrats.[12]

In 687, Pepin of Herstal, mayor of the palace of the Frankish sub-kingdom Austrasia, ended the strife between various kings and their mayors with his victory at Tertry.[13] Pepin was the grandson of two important figures of the Austrasian Kingdom: Saint Arnulf of Metz and Pepin of Landen.[14] Pepin's position as mayor of the palace allowed him gain power as the Mergovian kings' own waned.[12] Pepin was eventually succeeded by his son Charles, later known as Charles Martel.[15] Charles did not support a Merovingian successor upon the death of King Theuderic IV in 737, leaving the throne vacant.[16] Charles was able to pass on power and be succeeded in 741 by his sons Carloman and Pepin the Short, the father of Charlemagne.[17] The brothers placed the Merovingian Childeric III on the throne in 743.[18] Carloman abdicated his position in 747 to travel to Rome and entered a monastery, and his son Drogo took his place.[19]

Birth

Charlemagne's birth date is uncertain, but was most likely born in 748.[20][21][22][23] An older tradition, taking after 9th century biographer Einhard's report of Charlemagne being 72 at death, gives a birth year of 742.[24] Einhard, not knowing the emperor's true age, based this on the Roman emperor Augustus' age reported in Suetonius' biography.[25] German scholar Karl Werner challenged the acceptance of Einhard's date and cited a near-contemporary additions to annals which recorded Charlemagne's birth in 747.[26] Lorsch Abbey commemorated Charlemagne's date of birth as 2 April since the mid-9th century, and this date is likely genuine.[27][28] As the annalists recorded the start of the year from Easter rather than 1 January, Matthais Becher built off of Werner's work and showed that 2 April in the year recorded would have actually been in 748.[20] 2 April 748 has therefore become the accepted date among scholars.[29][20][21] The date of 742 has led to the belief that Charlemagne may have been an illegitimate child, as Pepin and Bertrada were bound by a private contract[30] at the time of his birth, but did not marry until 744.[31] Charlemagne's place of birth is also unknown but may have been at Frankish palaces in Vaires-sur-Marne or Quierzy.[32]

Accession and joint reign with Carloman

Charlemagne appears only sparsely in the Frankish annals before death of his father.[33] By 751 or 752, Pepin moved to depose Childeric and replace him as king.[18][34] Early Carolingian-influenced sources claim that Pepin's seizure of the throne was sanctioned by Pope Stephen II,[35] but modern historians dispute this.[36][18] It is possible that papal approval only came when Stephen traveled to Francia in 754, apparently to request Pippin's aid against the Lombards, and on this trip anointed Pepin as king, legitimizing his rule.[34][36] This papal visit is the earliest appearance of Charlemagne in the historical record, as he was sent to greet and escort the Pope, and he and his brother Carloman were anointed along with their father.[37] Around the same time, Pepin moved to sideline Drogo, sending him and his brother to a monastery.[38]

Charlemagne began issuing charters in his own name in 760, and is recorded as joining his father on campaign in 761.[39] During Pepin's reign, Aquitaine was constantly in rebellion against his rule.[40] Pepin fell ill on campaign in Aquitaine and died on 24 September 768, and Charlemagne and Carloman succeeded their father.[41] While the brothers maintained separate palaces and maintained separate spheres of influence ,it was still a joint rulership.[42] The immediate concern of the brothers was the ongoing uprising in Aquitane.[43] While they marched into Aquitaine together, Carloman abandoned the campaign and Charlemagne completed it on his own.[43] Charlemagne's capture of Duke Hunald marked the end of ten years of war in the attempt to bring Aquitaine in line.[43]

Carloman's refusal to participate in the war against Aquitaine led to a rift between the two kings.[43][44] It's uncertain why Carloman did not join Charlemagne. It is possible that the brothers disagreed over control over the territory,[43][45] or that Carloman was focusing on securing his rule in the north of Francia.[45] The brothers reported to the pope that their relations had returned to normal, though it's unclear if this was true.[46] Regardless of potential strife between the kings, they still maintained a joint rule out of practicality.[47] Both Charlemagne and Carloman worked to secure the support of the clergy and local elites to secure their positions.[48]

The political affairs of Italy became a focus of Charlemagne's. The Papacy had sought the protection of the Franks from the aggression of the Lombards since the time of Charles Martel, as the ability of the Byzantine Empire to control Central Italy was fading.[49] Pope Stephen III was elected in 768, but was briefly deposed by an antipope before being restored to Rome.[50] With factional struggle still occurring, Stephen sought the support of the Frankish kings.[51] Both brothers sent troops to Rome, each hoping to exert their own influence.[52] The Lombard king Desiderius also had interests in the affairs in Rome, and Charlemage moved to gain him as an ally.[53] Desiderius already had alliances with Bavaria and Benevento through the marriages of his daughters to their dukes,[54] and an alliance with Charlemagne would add to his influence.[53] Charlemagne's mother Betrada went on his behalf to Lombardy in 770, where she brokered the marriage alliance before returning to Francia with Charlemagne's new bride.[55] Desiderius's daughter is traditionally named Desiderata, though she may have been named Gerperga.[56][43] Pope Stephen was anxious at the prospect of the alliance, fearing the power it would give Desiderius. He sent a letter to both Frankish Kings decrying the marriage, while also separately seeking closer ties with Carloman.[57]

Carloman died suddenly on 4 December 771, leaving Charlemagne as sole King of the Franks.[58] Carloman's wife Gerberga and their children fled to the court of Desiderius[58] as Charlemagne moved immediately to secure his hold on his brother's territory.[59][60] In response, Charlemagne ended his marriage to Desiderius's daughter and married Hildegard.[60] This was both a reaction to Desiderius's sheltering of Carloman's family[61] as well as a move to secure the support of Hildegard's Gerold, a powerful magnate of Carloman's kingdom.[62][63]

Italian campaigns

Conquest of the Lombard kingdom

At his succession in 772, Pope Adrian I demanded the return of certain cities in the former exarchate of Ravenna in accordance with a promise at the succession of Desiderius. Instead, Desiderius took over certain papal cities and invaded the Pentapolis, heading for Rome. Adrian sent ambassadors to Charlemagne in autumn requesting he enforce the policies of his father, Pepin. Desiderius sent his own ambassadors denying the pope's charges. The ambassadors met at Thionville, and Charlemagne upheld the pope's side. Charlemagne demanded what the pope had requested, but Desiderius swore never to comply. Charlemagne and his uncle Bernard crossed the Alps in 773 and chased the Lombards back to Pavia, which they then besieged.[64] Charlemagne temporarily left the siege to deal with Adelchis, son of Desiderius, who was raising an army at Verona. The young prince was chased to the Adriatic littoral and fled to Constantinople to plead for assistance from Constantine V, who was waging war with Bulgaria.[65][66]

The siege lasted until the spring of 774 when Charlemagne visited the pope in Rome. There he confirmed his father's grants of land,[67] with some later chronicles falsely claiming that he also expanded them, granting Tuscany, Emilia, Venice and Corsica. The pope granted him the title patrician. He then returned to Pavia, where the Lombards were on the verge of surrendering. In return for their lives, the Lombards surrendered and opened the gates in early summer. Desiderius was sent to the abbey of Corbie, and his son Adelchis died in Constantinople, a patrician. Charles, unusually, had himself crowned with the Iron Crown and made the magnates of Lombardy pay homage to him at Pavia. Only Duke Arechis II of Benevento refused to submit and proclaimed independence. Charlemagne was then master of Italy as king of the Lombards. He left Italy with a garrison in Pavia and a few Frankish counts in place the same year.

Instability continued in Italy. In 776, Dukes Hrodgaud of Friuli and Hildeprand of Spoleto rebelled. Charlemagne rushed back from Saxony and defeated the Duke of Friuli in battle; the Duke was slain.[65] The Duke of Spoleto signed a treaty. Their co-conspirator, Arechis, was not subdued, and Adelchis, their candidate in Byzantium, never left that city. Northern Italy was now faithfully his.

Southern Italy

In 787, Charlemagne directed his attention towards the Duchy of Benevento,[68] where Arechis II was reigning independently with the self-given title of Princeps. Charlemagne's siege of Salerno forced Arechis into submission, and in return for peace, Arechis recognized Charlemagne's suzerainty and handed his son Grimoald III over as a hostage. After Arechis' death in 787, Grimoald was allowed to return to Benevento. In 788, the principality was invaded by Byzantine troops led by Adelchis, but his attempts were thwarted by Grimoald. The Franks assisted in the repulsion of Adelchis, but, in turn, attacked Benevento's territories several times,[69] obtaining small gains, notably the annexation of Chieti to the duchy of Spoleto.[70] Later, Grimoald tried to throw off Frankish suzerainty, but Charles' sons, Pepin of Italy and Charles the Younger, forced him to submit in 792.[71]

Southern expansion

Vasconia and the Pyrenees

The destructive war led by Pepin in Aquitaine, although brought to a satisfactory conclusion for the Franks, proved the Frankish power structure south of the Loire was feeble and unreliable. After the defeat and death of Waifer in 768, while Aquitaine submitted again to the Carolingian dynasty, a new rebellion broke out in 769 led by Hunald II, a possible son of Waifer. He took refuge with the ally Duke Lupus II of Gascony, but probably out of fear of Charlemagne's reprisal, Lupus handed him over to the new King of the Franks to whom he pledged loyalty, which seemed to confirm the peace in the Basque area south of the Garonne.[72] In the campaign of 769, Charlemagne seems to have followed a policy of "overwhelming force" and avoided a major pitched battle.[73]

Wary of new Basque uprisings, Charlemagne seems to have tried to contain Duke Lupus's power by appointing Seguin as the Count of Bordeaux (778) and other counts of Frankish background in bordering areas (Toulouse, County of Fézensac). The Basque Duke, in turn, seems to have contributed decisively or schemed the Battle of Roncevaux Pass (referred to as "Basque treachery"). The defeat of Charlemagne's army in Roncevaux (778) confirmed his determination to rule directly by establishing the Kingdom of Aquitaine (ruled by Louis the Pious) based on a power base of Frankish officials, distributing lands among colonisers and allocating lands to the Church, which he took as an ally. A Christianisation programme was put in place across the high Pyrenees (778).[72]

The new political arrangement for Vasconia did not sit well with local lords. As of 788 Adalric was fighting and capturing Chorson, Carolingian Count of Toulouse. He was eventually released, but Charlemagne, enraged at the compromise, decided to depose him and appointed his trustee William of Gellone. William, in turn, fought the Basques and defeated them after banishing Adalric (790).[72]

From 781 (Pallars, Ribagorça) to 806 (Pamplona under Frankish influence), taking the County of Toulouse for a power base, Charlemagne asserted Frankish authority over the Pyrenees by subduing the south-western marches of Toulouse (790) and establishing vassal counties on the southern Pyrenees that were to make up the Marca Hispanica.[74] As of 794, a Frankish vassal, the Basque lord Belasko (al-Galashki, 'the Gaul') ruled Álava, but Pamplona remained under Cordovan and local control up to 806. Belasko and the counties in the Marca Hispánica provided the necessary base to attack the Andalusians (an expedition led by William Count of Toulouse and Louis the Pious to capture Barcelona in 801). Events in the Duchy of Vasconia (rebellion in Pamplona, count overthrown in Aragon, Duke Seguin of Bordeaux deposed, uprising of the Basque lords, etc.) were to prove it ephemeral upon Charlemagne's death.

Roncesvalles campaign

According to the Muslim historian Ibn al-Athir, the Diet of Paderborn had received the representatives of the Muslim rulers of Zaragoza, Girona, Barcelona and Huesca. Their masters had been cornered in the Iberian peninsula by Abd ar-Rahman I, the Umayyad emir of Cordova. These "Saracen" (Moorish and Muwallad) rulers offered their homage to the king of the Franks in return for military support. Seeing an opportunity to extend Christendom and his own power, and believing the Saxons to be a fully conquered nation, Charlemagne agreed to go to Spain.

In 778, he led the Neustrian army across the Western Pyrenees, while the Austrasians, Lombards, and Burgundians passed over the Eastern Pyrenees. The armies met at Saragossa and Charlemagne received the homage of the Muslim rulers, Sulayman al-Arabi and Kasmin ibn Yusuf, but the city did not fall for him. Indeed, Charlemagne faced the toughest battle of his career. The Muslims forced him to retreat, so he decided to go home, as he could not trust the Basques, whom he had subdued by conquering Pamplona. He turned to leave Iberia, but as his army was crossing back through the Pass of Roncesvalles, one of the most famous events of his reign occurred: the Basques attacked and destroyed his rearguard and baggage train. The Battle of Roncevaux Pass, though less a battle than a skirmish, left many famous dead, including the seneschal Eggihard, the count of the palace Anselm, and the warden of the Breton March, Roland, inspiring the subsequent creation of The Song of Roland (La Chanson de Roland), regarded as the first major work in the French language.

Contact with Muslims

The conquest of Italy brought Charlemagne in contact with Muslims who, at the time, controlled the Mediterranean. Charlemagne's eldest son, Pepin the Hunchback, was much occupied with Muslims in Italy. Charlemagne conquered Corsica and Sardinia at an unknown date and in 799 the Balearic Islands. The islands were often attacked by Muslim pirates, but the counts of Genoa and Tuscany (Boniface) controlled them with large fleets until the end of Charlemagne's reign. Charlemagne even had contact with the caliphal court in Baghdad. In 797 (or possibly 801), the caliph of Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid, presented Charlemagne with an Asian elephant named Abul-Abbas and a clock.[75][76]

Wars with the Moors

In Hispania, the struggle against Islam continued unabated throughout the latter half of his reign. Louis was in charge of the Spanish border. In 785, his men captured Girona permanently and extended Frankish control into the Catalan littoral for the duration of Charlemagne's reign (the area remained nominally Frankish until the Treaty of Corbeil in 1258). The Muslim chiefs in the northeast of Islamic Spain were constantly rebelling against Cordovan authority, and they often turned to the Franks for help. The Frankish border was slowly extended until 795, when Girona, Cardona, Ausona and Urgell were united into the new Spanish March, within the old duchy of Septimania.

In 797, Barcelona, the greatest city of the region, fell to the Franks when Zeid, its governor, rebelled against Cordova and, failing, handed it to them. The Umayyad authority recaptured it in 799. However, Louis of Aquitaine marched the entire army of his kingdom over the Pyrenees and besieged it for two years, wintering there from 800 to 801, when it capitulated. The Franks continued to press forward against the emir. They probably took Tarragona and forced the submission of Tortosa in 809. The last conquest brought them to the mouth of the Ebro and gave them raiding access to Valencia, prompting the Emir al-Hakam I to recognise their conquests in 813.

Eastern campaigns

Saxon Wars

Charlemagne was engaged in almost constant warfare throughout his reign,[77] often at the head of his elite scara bodyguard squadrons. In the Saxon Wars, spanning thirty years and eighteen battles, he conquered Saxonia and proceeded to convert it to Christianity.

The Germanic Saxons were divided into four subgroups in four regions. Nearest to Austrasia was Westphalia and farthest away was Eastphalia. Between them was Engria and north of these three, at the base of the Jutland peninsula, was Nordalbingia.

In his first campaign, in 773, Charlemagne forced the Engrians to submit and cut down an Irminsul pillar near Paderborn.[78] The campaign was cut short by his first expedition to Italy. He returned in 775, marching through Westphalia and conquering the Saxon fort at Sigiburg. He then crossed Engria, where he defeated the Saxons again. Finally, in Eastphalia, he defeated a Saxon force, and its leader Hessi converted to Christianity. Charlemagne returned through Westphalia, leaving encampments at Sigiburg and Eresburg, which had been important Saxon bastions. He then controlled Saxony with the exception of Nordalbingia, but Saxon resistance had not ended.

Following his subjugation of the Dukes of Friuli and Spoleto, Charlemagne returned rapidly to Saxony in 776, where a rebellion had destroyed his fortress at Eresburg. The Saxons were once again defeated, but their main leader, Widukind, escaped to Denmark, his wife's home. Charlemagne built a new camp at Karlstadt. In 777, he called a national diet at Paderborn to integrate Saxony fully into the Frankish kingdom. Many Saxons were baptised as Christians.

In the summer of 779, he again invaded Saxony and reconquered Eastphalia, Engria and Westphalia. At a diet near Lippe, he divided the land into missionary districts and himself assisted in several mass baptisms (780). He then returned to Italy and, for the first time, the Saxons did not immediately revolt. Saxony was peaceful from 780 to 782.

He returned to Saxony in 782 and instituted a code of law and appointed counts, both Saxon and Frank. The laws were draconian on religious issues; for example, the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae prescribed death to Saxon pagans who refused to convert to Christianity. This led to renewed conflict. That year, in autumn, Widukind returned and led a new revolt. In response, at Verden in Lower Saxony, Charlemagne is recorded as having ordered the execution of 4,500 Saxon prisoners by beheading, known as the Massacre of Verden ("Verdener Blutgericht"). The killings triggered three years of renewed bloody warfare. During this war, the East Frisians between the Lauwers and the Weser joined the Saxons in revolt and were finally subdued.[79] The war ended with Widukind accepting baptism.[80] The Frisians afterwards asked for missionaries to be sent to them and a bishop of their own nation, Ludger, was sent. Charlemagne also promulgated a law code, the Lex Frisonum, as he did for most subject peoples.[81]

Thereafter, the Saxons maintained the peace for seven years, but in 792, Westphalia again rebelled. The Eastphalians and Nordalbingians joined them in 793, but the insurrection was unpopular and was put down by 794. An Engrian rebellion followed in 796, but the presence of Charlemagne, Christian Saxons and Slavs quickly crushed it. The last insurrection occurred in 804, more than thirty years after Charlemagne's first campaign against them, but also failed. According to Einhard:

The war that had lasted so many years was at length ended by their acceding to the terms offered by the King; which were renunciation of their national religious customs and the worship of devils, acceptance of the sacraments of the Christian faith and religion, and union with the Franks to form one people.

Submission of Bavaria

By 774, Charlemagne had invaded the Kingdom of Lombardy, and he later annexed the Lombardian territories and assumed its crown, placing the Papal States under Frankish protection.[82] The Duchy of Spoleto south of Rome was acquired in 774, while in the central western parts of Europe, the Duchy of Bavaria was absorbed and the Bavarian policy continued of establishing tributary marches, (borders protected in return for tribute or taxes) among the Slavic Sorbs and Czechs. The remaining power confronting the Franks in the east were the Avars. However, Charlemagne acquired other Slavic areas, including Bohemia, Moravia, Austria and Croatia.[82]

In 789, Charlemagne turned to Bavaria. He claimed that Tassilo III, Duke of Bavaria was an unfit ruler, due to his oath-breaking. The charges were exaggerated, but Tassilo was deposed anyway and put in the monastery of Jumièges.[83] In 794, Tassilo was made to renounce any claim to Bavaria for himself and his family (the Agilolfings) at the synod of Frankfurt; he formally handed over to the king all of the rights he had held.[84] Bavaria was subdivided into Frankish counties, as had been done with Saxony.

Avar campaigns

In 788, the Avars, an Asian nomadic group that had settled down in what is today Hungary (Einhard called them Huns), invaded Friuli and Bavaria. Charlemagne was preoccupied with other matters until 790 when he marched down the Danube and ravaged Avar territory to the Győr. A Lombard army under Pippin then marched into the Drava valley and ravaged Pannonia. The campaigns ended when the Saxons revolted again in 792.

For the next two years, Charlemagne was occupied, along with the Slavs, against the Saxons. Pippin and Duke Eric of Friuli continued, however, to assault the Avars' ring-shaped strongholds. The great Ring of the Avars, their capital fortress, was taken twice. The booty was sent to Charlemagne at his capital, Aachen, and redistributed to his followers and to foreign rulers, including King Offa of Mercia. Soon the Avar tuduns had lost the will to fight and travelled to Aachen to become vassals to Charlemagne and to become Christians. Charlemagne accepted their surrender and sent one native chief, baptised Abraham, back to Avaria with the ancient title of khagan. Abraham kept his people in line, but in 800, the Bulgarians under Khan Krum attacked the remains of the Avar state.

In 803, Charlemagne sent a Bavarian army into Pannonia, defeating and bringing an end to the Avar confederation.[85]

In November of the same year, Charlemagne went to Regensburg where the Avar leaders acknowledged him as their ruler.[85] In 805, the Avar khagan, who had already been baptised, went to Aachen to ask permission to settle with his people south-eastward from Vienna.[85] The Transdanubian territories became integral parts of the Frankish realm, which was abolished by the Magyars in 899–900.

Northeast Slav expeditions

In 789, in recognition of his new pagan neighbours, the Slavs, Charlemagne marched an Austrasian-Saxon army across the Elbe into Obotrite territory. The Slavs ultimately submitted, led by their leader Witzin. Charlemagne then accepted the surrender of the Veleti under Dragovit and demanded many hostages. He also demanded permission to send missionaries into this pagan region unmolested. The army marched to the Baltic before turning around and marching to the Rhine, winning much booty with no harassment. The tributary Slavs became loyal allies. In 795, when the Saxons broke the peace, the Abotrites and Veleti rebelled with their new ruler against the Saxons. Witzin died in battle and Charlemagne avenged him by harrying the Eastphalians on the Elbe. Thrasuco, his successor, led his men to conquest over the Nordalbingians and handed their leaders over to Charlemagne, who honoured him. The Abotrites remained loyal until Charles' death and fought later against the Danes.

Southeast Slav expeditions

When Charlemagne incorporated much of Central Europe, he brought the Frankish state face to face with the Avars and Slavs in the southeast.[86] The most southeast Frankish neighbours were Croats, who settled in Lower Pannonia and Duchy of Croatia. While fighting the Avars, the Franks had called for their support.[87] During the 790s, he won a major victory over them in 796.[88] Duke Vojnomir of Lower Pannonia aided Charlemagne, and the Franks made themselves overlords over the Croats of northern Dalmatia, Slavonia and Pannonia.[88]

The Frankish commander Eric of Friuli wanted to extend his dominion by conquering the Littoral Croat Duchy. During that time, Dalmatian Croatia was ruled by Duke Višeslav of Croatia. In the Battle of Trsat, the forces of Eric fled their positions and were routed by the forces of Višeslav.[89] Eric was among those killed, which was a great blow for the Carolingian Empire.[86][90][89]

Charlemagne also directed his attention to the Slavs to the west of the Avar khaganate: the Carantanians and Carniolans. These people were subdued by the Lombards and Bavarii and made tributaries, but were never fully incorporated into the Frankish state.

Reign as emperor

Coronation

In April 799, Pope Leo III, who had faced difficulties since his accession in 795, was attacked in Rome and accused of various crimes by political enemies.[91] Leo escaped and fled north to seek Charlemagne's help.[92] Charlemagne continued his campaign against the Saxons before breaking off to meet Leo at Paderborn in September.[93][94] Charlemagne, hearing evidence from both the Pope and his enemies, sent Leo back to Rome along with royal legates, who had instructions to reinstate the Pope and investigate the matter further.[95] It was not until August of the next year that Charlemagne himself made plans to go to Rome, after an extensive tour of his lands in Neustria.[95][96] Charlemagne met Leo in November near Mentana, at the twelfth milestone outside Rome, the traditional location where Roman emperors began their formal entry to the city.[96] In Rome, Leo stood trial before the king and swore his innocence of all charges made against him.[93] On 25 December 800, at mass on Christmas Day, Leo acclaimed Charlemagne as emperor and crowned him. In doing so, Charlemagne became the first reigning emperor in the west since the deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476.[97] His son Charles the Younger was anointed as king by Leo at the same time.[98]

Historians differ as to intentions behind the imperial coronation, the extent to which Charlemagne was aware of it or participated in its planning, and the significance of the events to those present and to Charlemagne's reign.[93] Contemporary Frankish and papal sources differ in their emphasis and representation of events.[99] Charlemagne's 9th century biographer Einhard insists that he would not have entered the church had he known of the Pope's plan has variously been taken as truthful or as a "literary device" used as a sign of Charlemagne's humility.[100] Roger Collins argues that the actions surrounding the coronation indicate that it was planned by Charlemagne as early as his meeting with Leo in 799,[101] and Johannes Fried argues Charlemagne planned to adopt the title of emperor by 798 "at the latest."[102] In the years before the coronation, Charlemagne's courtier Alcuin had referred to Charlemagne's realm as an Imperium Christianum ("Christian Empire"), wherein, "just as the inhabitants of the Roman Empire had been united by a common Roman citizenship", presumably this new empire would be united by a common Christian faith.[103] This is the view of Henri Pirenne when he says "Charles was the Emperor of the ecclesia as the Pope conceived it, of the Roman Church, regarded as the universal Church".[104]

For both Leo and Charlemagne, the Roman Empire remained a significant contemporary power in European politics, especially in Italy. The Byzantines continued to hold a substantial portion of Italy, with borders not far south of Rome. In sitting in judgment of the Pope, Charlemagne could have been seen as usurping the prerogatives of the emperor in Constantinople.[105][lower-alpha 3] One of the earliest narrative sources, the Annals of Lorsch present the position of Emperess Irene, a woman, on the throne indicated an absence in the imperial title that Leo and Charlemagne could therefore fill.[108][105] Pirenne disputes this, saying that the coronation "was not in any sense explained by the fact that at this moment a woman was reigning in Constantinople."[109] Leo's main motivations may have been the desire to increase his own standing after his political difficulties, showing himself as a king-maker and securing Charlemagne as his powerful ally and protector.[110] The Byzantine Empire's lack of ability to influence events in Italy and support the papacy were also important in Leo's position.[111][110] The act of Leo crowning Charlemagne can also be viewed as showing the Pope's spiritual power over Charlemagne as a temporal ruler.[112] The Royal Frankish Annals, on the other hand, records Leo prostrating himself before Charlemagne after crowning him, an act of submission standard in Roman coronation rituals from the time of Diocletian. This account represents Leo, rather being the superior of Charlemagne, merely acting as an agent of the Roman people in recognizing their acclimation of Charlemagne as emperor.[113]

Henry Mayr-Harting argues that assumption of the imperial title by Charlemagne was an effort to incorporate the Saxons into the Frankish realm, as they did not have a native tradition of kingship.[114] However, Costambeys, Innes, and MacLean note in The Carolingian World that "since Saxony had not been in the Roman empire it is hard to see on what basis an emperor would have been any more welcomed."[110] These authors argue that the decision to take the title of emperor was more aimed at furthering Charlemagne's influence in Italy, as an appeal to traditional authority recognized by Italian elites both within and especially outside his current control.[110]

Collins concurs that becoming emperor gave Charlemagne "the right to try to impose his rule over the whole of [Italy]", and regards this as a motivator for the coronation.[115] He also notes the "element of political and military risk"[115] inherent in the affair, due to the opposition of the Byzantine Empire as well as potential opposition from the Frankish elite as the imperial title could draw him further into Mediterranean politics.[116] Collins sees several actions of Charlemagne as attempts to ensure his new title was cast in a distinctly Frankish context.[117]

Charlemagne's coronation led to a centuries-long ideological conflict between his successors and Constantinople, termed the problem of two emperors,[lower-alpha 4] as it could be seen as a repudiation of the Byzantine singular claim to imperial title as preeminent among Christian rulers.[118] Charlemagne may have had a more limited view of his role, seeing the title simply representing dominion over the lands he already ruled.[119] Still, the title of emperor gave Charlemagne enhanced prestige and ideological authority.[120][121] He immediately incorporated his new title into documents issued, adopting the formula Charles, most serene Augustus, crowned by God, great peaceful emperor governing the Roman empire, and who is by the mercy of God king of the Franks and the Lombards[lower-alpha 5] as opposed to the earlier form Charles, by the grace of God king of the Franks and Lombards and patrician of the Romans.[lower-alpha 6][2] The avoidance of the specific claim of being a "Roman emperor" as an opposed to the more neutral "emperor governing the Roman empire" may have been to improve relations with the Byzantines.[122] This phrasing, alongside the continuation of his earlier royal titles, may also represent a view of his role as emperor as merely being the ruler of the people of the city of Rome, just as he was of the Franks and the Lombards.[122][123]

Governing the empire

Charlemagne left Italy in the summer of 801 after judging several ecclesiastical disputes in Rome and further stops in Ravenna, Pavia, and Bologna.[124] He would not return to Rome again.[120] Although the trends of his later realm began in the 790s,[125] period of Charlemagne's reign from 801 onward marks a "distinct phase"[126] characterised by a more stationary rule from the palace at Aachen.[120] Expansion of the realm largely ended, marked by the establishment of marches to defend the empire's frontiers.[127] While there continued to be conflict until the end of Charlemagne's reign, the relative peace of the imperial period saw an increased focus on internal governance through the issuing of laws and capitularies.

Charlemagne did not campaign in either 802 or 803.[128] The Capitulare missorum generale issued in 802, called the "programmatic capitulary", was an expansive piece of legislation, with provisions governing the conduct of royal officials and requiring a loyalty oath to the emperor to be taken by all free men under his rule.[129][130] The capitulary reformed the institution of the missi dominici, officials who would now be assigned in pairs (a cleric and a lay aristocrat) to administer justice and oversee governance in defined territories.[131] The emperor also ordered revisions of the Lombard and Frankish law codes.[132]

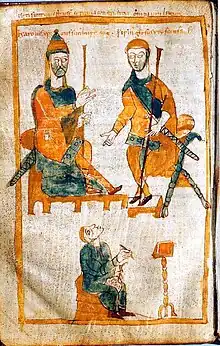

In addition to the missi, Charlemagne also ruled the empire through his sons as sub-kings. Pepin and Louis had been appointed kings of the Italy and Aquitaine respectively in 781, though both were children at the time and were ruled by regents in their minority.[133] Though both had some devolved authority as kings in adulthood, Charlemagne still had ultimate authority and intervened in matters directly.[134] Charles, the eldest son, had been given rule over lands in Neustria in 789 or 790, and had been made a king in 800.[135]

The 806 charter Divisio Regnorum ("division of the realm"), set the terms of succession of the empire in the event of Charlemagne's death.[136] Charles, as eldest son, was given the largest share of the inheritance, with rule of Francia proper along with Saxony, Nordgau, and parts of Alemannia. The two younger sons were confirmed in their kingdoms and gained additional territories, with most of Bavaria and Alemmannia given to Pepin and Provence, Septimania, and parts of Burgundy to Louis.[137] Charlemagne did not address the inheritance of the imperial title.[135] The Divisio also addressed the event of any of the brothers, and urged peace between them and between any of their nephews who might inherit.[138]

Conflict and diplomacy with the east

Following his coronation, Charlemagne sought recognition of his imperial title from Constantinople.[139] Several delegations were exchanged between Charlemagne and Irene in 802 and 803. A Byzantine chronicler claims that Charlemagne made an offer of marriage to Irene, which she was close to accepting.[140] Irene, however, was deposed and replaced by Nikephoros I, who was unwilling to recognize Charlemagne as emperor.[140] The two empires would come into conflict over control of the Adriatic Sea (especially Istria and Veneto) several times during Nikephoros' reign, before peace negotiations commenced in 810.[141] Charlemagne's envoys would make peace with emperor Michael I, who had succeeded his father-in-law Nikephoros. As part of the peace, Michael recognized Charlemagne as emperor and basileus.[142] It was only following this recognition that Charlemagne would issue coins including the imperial title, though coins minted by the pope in Rome had used the titles as early as 800.[143]

Cordial relations were retained with Abbasid Caliphate during the first decade of imperial rule. Harun al-Rashid, himself at war with the Byzantines during this period, sought to ensure Charlemagne's relations with Nikephoros remained poor.[144] As part of his outreach, Harun gave Charlemagne nominal rule of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, as well as other gifts.[144] Harun died in 809, leading to competing claimants over succession to the caliphate. Under Harun's successors, conditions for Christians and Jews under the caliphate worsened, and churches and synagogues were destroyed.[145] Unable to intervene directly, Charlemagne sent aid in the form of specially minted coins (which also served as propaganda for the emperor in the form of inscriptions and portraiture) and arms to Christians under the caliphate in order to restore and defend churches and monasteries.[146] The souring of relations with Baghdad after Harun's death may have been the impetus for the renewed negotiations with Constantinople that would lead to Charlemagne's peace with Michael in 811.[147]

As emperor, Charlemagne became involved in a religious dispute between eastern and western Christians over the recitation of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, the fundamental statement of orthodox Christian belief. The original text of the creed adopted at the Council of Constantinople professed that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father. However, a developed tradition in western Europe that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father "and the Son", inserting the Latin term filioque.[148] This difference in tradition did not cause significant conflict until 807, when Frankish monks in Bethlehem were denounced as heretics by a Greek monk for their insertion of filioque.[148] The monks appealed the dispute to Rome, where Pope Leo affirmed the text of the creed omitting the phrase and also passed the report on to Charlemagne.[149] Charlemagne summoned a council at Aachen in 809, which defended the used of filioque, and sent this decision to Rome. Leo consented that the Franks could maintain their traditional, but asserted that the canonical creed did not include filioque.[150] Leo went so far as to commission two silver shields with the creed in Latin and Greek which he hung in St. Peter's Basilica.[148][151]

Danish attacks

After the conquest of Nordalbingia, the Frankish frontier was brought into contact with Scandinavia. The pagan Danes, "a race almost unknown to his ancestors, but destined to be only too well known to his sons"[152] as Charles Oman described them, inhabiting the Jutland peninsula, had heard many stories from Widukind and his allies who had taken refuge with them about the dangers of the Franks and the fury which their Christian king could direct against pagan neighbours.

In 808, the king of the Danes, Godfred, expanded the vast Danevirke across the isthmus of Schleswig. This defence, last employed in the Danish-Prussian War of 1864, was at its beginning a 30 km (19 mi) long earthenwork rampart. The Danevirke protected Danish land and gave Godfred the opportunity to harass Frisia and Flanders with pirate raids. He also subdued the Frank-allied Veleti and fought the Abotrites.

Godfred invaded Frisia, joked of visiting Aachen, but was murdered before he could do any more, either by a Frankish assassin or by one of his own men. Godfred was succeeded by his nephew Hemming, who concluded the Treaty of Heiligen with Charlemagne in late 811.

Final years and death

The Carolingian dynasty had multiple losses in 810, as Charlemagne's sister Gisela, his daughter Rotrude, and his son Pepin of Italy died.[153] His eldest sons Pepin the Hunchback and Charles the Younger both died the next year.[154] The deaths of Charles and Pepin of Italy left Charlemagne's earlier plans for succession in disarray. In the wake of these deaths, he declared Pepin's son Bernard ruler of Italy, and his own only surviving son Louis as heir to the rest of the empire.[155] He also completed a new will detailing the disposition of his property, with bequests to the Church as well as all of his children and grandchildren.[156] Einhard (possibly relying on tropes from Suetonius's The Twelve Caesars) recounts that Charlemagne viewed the deaths of his family members, astronomical phenomena, and other misfortunes in his last years as signs of his own impending death.[157] In his final year, Charlemagne continued to govern the empire and church with energy, ordering bishops to assemble in five ecclesiastical councils.[158] These culminated in a large assembly at Aachen, where Charlemagne formally crowned Louis as his co-emperor and Bernard as king in a ceremony on 11 September 813.[159]

Charlemagne became ill in the autumn of 813 and spent his last months praying, fasting, and studying the Gospels.[157] He developed pleurisy, and became completely bedridden for seven days before dying on the morning of 28 January 814.[160] Thegan, a biographer of Louis, records the emperor's last words as "Into your hands, Lord, I commend my spirit", quoting from Luke 23:46.[161] Charlemagne's body was prepared and buried in the chapel at Aachen by his daughters and palace officials the same day.[162] Louis arrived at Aachen thirty days after his father's death, making a formal adventus, taking charge of the palace and the empire.[163] Charlemagne's remains were exhumed by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa in 1165, and reinterred in a new casket by Frederick II in 1215.[164]

Administration

Organisation

The Carolingian king exercised the bannum, the right to rule and command. Under the Franks, it was a royal prerogative but could be delegated.[165] He had supreme jurisdiction in judicial matters, made legislation, led the army, and protected both the Church and the poor. His administration was an attempt to organise the kingdom, church and nobility around him. As an administrator, Charlemagne stands out for his many reforms: monetary, governmental, military, cultural and ecclesiastical. He is the main protagonist of the "Carolingian Renaissance".

Military

Charlemagne's success rested primarily on novel siege technologies and excellent logistics[166] rather than the long-claimed "cavalry revolution" led by Charles Martel in 730s. However, the stirrup, which made the "shock cavalry" lance charge possible, was not introduced to the Frankish kingdom until the late eighth century.[167]

Horses were used extensively by the Frankish military because they provided a quick, long-distance method of transporting troops, which was critical to building and maintaining the large empire.[167]

Economic and monetary reforms

Charlemagne had an important role in determining Europe's immediate economic future. Pursuing his father's reforms, Charlemagne abolished the monetary system based on the gold sou. Instead, he and the Anglo-Saxon King Offa of Mercia took up Pippin's system for pragmatic reasons, notably a shortage of the metal.

The gold shortage was a direct consequence of the conclusion of peace with Byzantium, which resulted in ceding Venice and Sicily to the East and losing their trade routes to Africa. The resulting standardisation economically harmonised and unified the complex array of currencies that had been in use at the commencement of his reign, thus simplifying trade and commerce.

Charlemagne established a new standard, the livre carolinienne (from the Latin libra, the modern pound), which was based upon a pound of silver—a unit of both money and weight—worth 20 sous (from the Latin solidus [which was primarily an accounting device and never actually minted], the modern shilling) or 240 deniers (from the Latin denarius, the modern penny). During this period, the livre and the sou were counting units; only the denier was a coin of the realm.

Charlemagne instituted principles for accounting practice by means of the Capitulare de villis of 802, which laid down strict rules for the way in which incomes and expenses were to be recorded.

Charlemagne applied this system to much of the European continent, and Offa's standard was voluntarily adopted by much of England. After Charlemagne's death, continental coinage degraded, and most of Europe resorted to using the continued high-quality English coin until about 1100.

Jews in Charlemagne's realm

Early in Charlemagne's rule he tacitly allowed Jews to monopolise money lending.[168] He invited Italian Jews to immigrate, as royal clients independent of the feudal landowners, and form trading communities in the agricultural regions of Provence and the Rhineland. Their trading activities augmented the otherwise almost exclusively agricultural economies of these regions.[169] His personal physician was Jewish,[170] and he employed a Jew named Isaac as his personal representative to the Muslim caliphate of Baghdad.[171]

Education reforms

_Ystoria_Carolo_Magno_-_Chronicl_Turpin.jpg.webp)

Part of Charlemagne's success as a warrior, an administrator and ruler can be traced to his admiration for learning and education. His reign is often referred to as the Carolingian Renaissance because of the flowering of scholarship, literature, art and architecture that characterise it. Charlemagne came into contact with the culture and learning of other countries (especially Moorish Spain, Anglo-Saxon England,[172] and Lombard Italy) due to his vast conquests. He greatly increased the provision of monastic schools and scriptoria (centres for book-copying) in Francia.

Charlemagne was a lover of books, sometimes having them read to him during meals. He was thought to enjoy the works of Augustine of Hippo.[173] His court played a key role in producing books that taught elementary Latin and different aspects of the church. It also played a part in creating a royal library that contained in-depth works on language and Christian faith.[174]

Charlemagne encouraged clerics to translate Christian creeds and prayers into their respective vernaculars as well to teach grammar and music. Due to the increased interest of intellectual pursuits and the urging of their king, the monks accomplished so much copying that almost every manuscript from that time was preserved. At the same time, at the urging of their king, scholars were producing more secular books on many subjects, including history, poetry, art, music, law, theology, etc. Due to the increased number of titles, private libraries flourished. These were mainly supported by aristocrats and churchmen who could afford to sustain them. At Charlemagne's court, a library was founded and a number of copies of books were produced, to be distributed by Charlemagne.[175][6] Book production was completed slowly by hand and took place mainly in large monastic libraries. Books were so in demand during Charlemagne's time that these libraries lent out some books, but only if that borrower offered valuable collateral in return.[6]

.JPG.webp)

Most of the surviving works of classical Latin were copied and preserved by Carolingian scholars. Indeed, the earliest manuscripts available for many ancient texts are Carolingian. It is almost certain that a text which survived to the Carolingian age survives still.

The pan-European nature of Charlemagne's influence is indicated by the origins of many of the men who worked for him: Alcuin, an Anglo-Saxon from York; Theodulf, a Visigoth, probably from Septimania; Paul the Deacon, Lombard; Italians Peter of Pisa and Paulinus of Aquileia; and Franks Angilbert, Angilram, Einhard and Waldo of Reichenau.

Charlemagne promoted the liberal arts at court, ordering that his children and grandchildren be well-educated, and even studying himself (in a time when even leaders who promoted education did not take time to learn themselves) under the tutelage of Peter of Pisa, from whom he learned grammar; Alcuin, with whom he studied rhetoric, dialectic (logic), and astronomy (he was particularly interested in the movements of the stars); and Einhard, who tutored him in arithmetic.[176]

His great scholarly failure, as Einhard relates, was his inability to write: when in his old age he attempted to learn—practising the formation of letters in his bed during his free time on books and wax tablets he hid under his pillow—"his effort came too late in life and achieved little success", and his ability to read—which Einhard is silent about, and which no contemporary source supports—has also been called into question.[176]

In 800, Charlemagne enlarged the hostel at the Muristan in Jerusalem and added a library to it. He certainly had not been personally in Jerusalem.[177][178]

Writing reforms

During Charles' reign, the Roman half uncial script and its cursive version, which had given rise to various continental minuscule scripts, were combined with features from the insular scripts in use in Irish and English monasteries. Carolingian minuscule was created partly under the patronage of Charlemagne. Alcuin, who ran the palace school and scriptorium at Aachen, was probably a chief influence.

The revolutionary character of the Carolingian reform, however, can be overemphasised; efforts at taming Merovingian and Germanic influence had been underway before Alcuin arrived at Aachen. The new minuscule was disseminated first from Aachen and later from the influential scriptorium at Tours, where Alcuin retired as an abbot.

Appearance

Manner

Einhard tells in his twenty-fourth chapter:

Charles was temperate in eating, and particularly so in drinking, for he abominated drunkenness in anybody, much more in himself and those of his household; but he could not easily abstain from food, and often complained that fasts injured his health. He very rarely gave entertainments, only on great feast-days, and then to large numbers of people. His meals ordinarily consisted of four courses, not counting the roast, which his huntsmen used to bring in on the spit; he was more fond of this than of any other dish. While at table, he listened to reading or music. The subjects of the readings were the stories and deeds of olden time: he was fond, too, of St. Augustine's books, and especially of the one titled The City of God.[179]

Charlemagne threw grand banquets and feasts for special occasions such as religious holidays and four of his weddings. When he was not working, he loved Christian books, horseback riding, swimming, bathing in natural hot springs with his friends and family, and hunting.[180] Franks were well known for horsemanship and hunting skills.[180] Charles was a light sleeper and would stay in his bed chambers for entire days at a time due to restless nights. During these days, he would not get out of bed when a quarrel occurred in his kingdom, instead summoning all members of the situation into his bedroom to be given orders. Einhard tells again in the twenty-fourth chapter: "In summer after the midday meal, he would eat some fruit, drain a single cup, put off his clothes and shoes, just as he did for the night, and rest for two or three hours. He was in the habit of awaking and rising from bed four or five times during the night."[180]

Language

Einhard speaks of Charlemagne's patrius sermo, "father" or "native toungue".[32] Most scholars have identified this as a form of Old High German, probably a Rhenish Franconian dialect.[181][182][183] Einhard wrote from his experiences in Charlemagne's court in the 790s onward. Due to the prevalence in Francia of the "rustic Roman" language that was rapidly developing into Old French, he was probably functionally bilingual in both Germanic and Romance dialects from a young age.[32] Charlemagne also spoke Latin, and according to Einhard could understand and perhaps speak some Greek.[184] Fried considers it likely that Charlemagne would have been literate,[185] though Einhard recorded that he only attempted to learn to write later in life.[186]

The largely fictional account of Charlemagne's Iberian campaigns by Pseudo-Turpin, written some three centuries after his death, gave rise to a legend that the king also spoke Arabic.[187]

Physical appearance

Charlemagne's personal appearance is known from a good description by Einhard after his death in the biography Vita Karoli Magni. Einhard states:[188]

He was heavily built, sturdy, and of considerable stature, although not exceptionally so, since his height was seven times the length of his own foot. He had a round head, large and lively eyes, a slightly larger nose than usual, white but still attractive hair, a bright and cheerful expression, a short and fat neck, and he enjoyed good health, except for the fevers that affected him in the last few years of his life. Towards the end, he dragged one leg. Even then, he stubbornly did what he wanted and refused to listen to doctors, indeed he detested them, because they wanted to persuade him to stop eating roast meat, as was his wont, and to be content with boiled meat.

The physical portrait provided by Einhard is confirmed by contemporary depictions such as coins and his 8-inch (20 cm) bronze statuette kept in the Louvre. In 1861, Charlemagne's tomb was opened by scientists who reconstructed his skeleton and estimated it to be measured 1.95 metres (6 ft 5 in).[189] A 2010 estimate of his height from an X-ray and CT scan of his tibia was 1.84 metres (6 ft 0 in). This puts him in the 99th percentile of height for his period, given that average male height of his time was 1.69 metres (5 ft 7 in). The width of the bone suggested he was slim in build.[190]

Dress

Charlemagne wore the traditional costume of the Frankish people, described by Einhard thus:[191]

He used to wear the national, that is to say, the Frank, dress—next his skin a linen shirt and linen breeches, and above these a tunic fringed with silk; while hose fastened by bands covered his lower limbs, and shoes his feet, and he protected his shoulders and chest in winter by a close-fitting coat of otter or marten skins.

He wore a blue cloak and always carried a sword typically of a golden or silver hilt. He wore intricately jeweled swords to banquets or ambassadorial receptions. Nevertheless:[191]

He despised foreign costumes, however handsome, and never allowed himself to be robed in them, except twice in Rome, when he donned the Roman tunic, chlamys, and shoes; the first time at the request of Pope Hadrian, the second to gratify Leo, Hadrian's successor.

On great feast days, he wore embroidery and jewels on his clothing and shoes. He had a golden buckle for his cloak on such occasions and would appear with his great diadem, but he despised such apparel according to Einhard, and usually dressed like the common people.[191]

Homes

Charlemagne had residences across his kingdom, including numerous private estates that were governed in accordance with the Capitulare de villis. A 9th-century document detailing the inventory of an estate at Asnapium listed amounts of livestock, plants and vegetables and kitchenware including cauldrons, drinking cups, brass kettles and firewood. The manor contained seventeen houses built inside the courtyard for nobles and family members and was separated from its supporting villas.[192]

Wives, concubines, and children

Charlemagne had eighteen children with seven of his ten known wives or concubines.[193][194] Nonetheless, he had only four legitimate grandsons, the four sons of his fourth son, Louis. In addition, he had a grandson (Bernard of Italy, the only son of his third son, Pepin of Italy), who was illegitimate but included in the line of inheritance. Among his descendants are several royal dynasties, including the Habsburg, and Capetian dynasties. By consequence, most if not all established European noble families ever since can genealogically trace some of their background to Charlemagne.

|

Wives and their children

|

Concubines and their children

|

Children

During the first peace of any substantial length (780–782), Charles began to appoint his sons to positions of authority. In 781, during a visit to Rome, he made his two youngest sons kings, crowned by the Pope.[lower-alpha 8][lower-alpha 9] The elder of these two, Carloman, was made the king of Italy, taking the Iron Crown that his father had first worn in 774, and in the same ceremony was renamed "Pepin"[65][67] (not to be confused with Charlemagne's eldest, possibly illegitimate son, Pepin the Hunchback). The younger of the two, Louis, became King of Aquitaine. Charlemagne ordered Pepin and Louis to be raised in the customs of their kingdoms, and he gave their regents some control of their subkingdoms, but kept the real power, though he intended his sons to inherit their realms. He did not tolerate insubordination in his sons: in 792, he banished Pepin the Hunchback to Prüm Abbey because the young man had joined a rebellion against him.

Charles was determined to have his children educated, including his daughters, as his parents had instilled the importance of learning in him at an early age.[201] His children were also taught skills in accord with their aristocratic status, which included training in riding and weaponry for his sons, and embroidery, spinning and weaving for his daughters.[202]

The sons fought many wars on behalf of their father. Charles was mostly preoccupied with the Bretons, whose border he shared and who insurrected on at least two occasions and were easily put down. He also fought the Saxons on multiple occasions. In 805 and 806, he was sent into the Böhmerwald (modern Bohemia) to deal with the Slavs living there (Bohemian tribes, ancestors of the modern Czechs). He subjected them to Frankish authority and devastated the valley of the Elbe, forcing tribute from them. Pippin had to hold the Avar and Beneventan borders and fought the Slavs to his north. He was uniquely poised to fight the Byzantine Empire when that conflict arose after Charlemagne's imperial coronation and a Venetian rebellion. Finally, Louis was in charge of the Spanish March and fought the Duke of Benevento in southern Italy on at least one occasion. He took Barcelona in a great siege in 801.

Charlemagne kept his daughters at home with him and refused to allow them to contract sacramental marriages (though he originally condoned an engagement between his eldest daughter Rotrude and Constantine VI of Byzantium, this engagement was annulled when Rotrude was 11).[203] Charlemagne's opposition to his daughters' marriages may possibly have intended to prevent the creation of cadet branches of the family to challenge the main line, as had been the case with Tassilo of Bavaria. However, he tolerated their extramarital relationships, even rewarding their common-law husbands and treasuring the illegitimate grandchildren they produced for him. He also refused to believe stories of their wild behaviour. After his death the surviving daughters were banished from the court by their brother, the pious Louis, to take up residence in the convents they had been bequeathed by their father. At least one of them, Bertha, had a recognised relationship, if not a marriage, with Angilbert, a member of Charlemagne's court circle.[204][205]

Legacy

Political legacy

The stability and peace of Charlemagne's reign would not long outlast him. Louis' reign was marked by strife, including multiple rebellions of his own sons. Following Louis' death, the empire was divided between West, East, and Middle Francia.[206] Middle Francia saw several more divisions over subsequent generations.[207] Carolingians would rule with some interruptions in East Francia until 911[97] and in West Francia (which would become France) until 987.[208] After 887, the imperial title was held sporadically by a series of non-dynastic Italian rulers[209] before lapsing in 924.[210] East Francian King Otto the Great conquered Italy and was crowned emperor in 962.[211] The Holy Roman Empire founded by Otto would last until its dissolution in 1806.[212]

Charlemagne served as a model for medieval rulership "at least until the final end of empire in the West in the early nineteenth century."[213] Charlemagne is often given the epithet "the father of Europe" because of the influence of his reign, and the legacy he left across the large area of the continent he ruled.[214] The political structures Charlemagne established remained in place through his Carolingian successors, and continued to have influence into the eleventh century.[215] During his reign, groundwork was laid for the process of concentration of power in military aristocrats that would characterize the later Middle Ages.[216]

Despite the end of ruling Carolingian lines, Charlemagne is considered a direct ancestor of European ruling houses, including the Capetian dynasty,[lower-alpha 10] the Ottonian dynasty,[lower-alpha 11] the House of Luxembourg,[lower-alpha 12] the House of Ivrea[lower-alpha 13] and the House of Habsburg.[lower-alpha 14] The Ottonians and Capetians, direct successors of the Carolingans, drew on the legacy of Charlemagne to bolster their legitimacy and prestige. Ottonians and future emperors would continue to hold their German coronations at Aachen through the Middle Ages.[223] The marriage of Philip II of France to Isabella of Hainault, a direct descendant of Charlemagne was seen as a sign of increased legitimacy for their son Louis VIII, and association with Charlemagne by French kings continue until the monarchy's end.[224] Frederick Barbarossa, Charles V,[225] and Napoleon all directly cited the influence of and associated themselves with Charlemagne.[226]

The city of Aachen has, since 1949, awarded an international prize (called the Karlspreis der Stadt Aachen) in honour of Charlemagne. It is awarded annually to those who have promoted the idea of European unity.[226] Winners of the prize include Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, the founder of the pan-European movement, Alcide De Gasperi, and Winston Churchill.

Depictions in medieval literature

Charlemagne was a frequent subject of and inspiration for medieval writers after his death. Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni "can be said to have revived the defunct literary genre of the secular biography."[227] Einhard drew on classical sources such as Suetonius' De vita Caesarum, the orations of Cicero, and Tacitus' Agricola to frame the structure and style of his work.[228] The Carolingian period also saw an revival in the genre of mirrors for princes genre.[229] The author of the Visio Karoli Magni written around 865 uses facts gathered apparently from Einhard and his own observations on the decline of Charlemagne's family after the dissensions war (840–43) as the basis for a visionary tale of Charles' meeting with a prophetic spectre in a dream.[230] Notker's Gesta Karoli Magni, written for Charlemagne's great-grandson Charles the Fat, presents moral anecdotes to highlight the emperor's qualities as a ruler.[231][232]

Charlemagne was depicted as one of the Nine Worthies, becoming a fixture in medieval literature and art as an exemplar of a Christian king.[233] Charlemagne is the main figure of the medieval literary cycle known as Matter of France. Works of this cycle, which originated during the period of the Crusades centre depictions of the emperor as a leader of Christian knights in wars against Muslims. The cycle includes chansons de geste (epic poems) such as the Roland, and chronicles such as the Historia Caroli Magni.[234] Geoffrey of Monmouth's legends of King Arthur and his knights may have drawn on the legendary depiction of Charlemagne and his knights as a source and archetype.[235]

In the Divine Comedy, the spirit of Charlemagne appears to Dante in the Heaven of Mars, among the other "warriors of the faith".[236]

Religious impact and veneration

Charlemagne the Great | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Charlemagne Empereur d'Occident by Louis-Félix Amiel, circa 1837. | |

| Confessor and Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Beatified | Recognized in the 18th century, Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran, Rome, Holy Roman Empire by Pope Benedict XIV (cultus approved) |

| Canonized | 29 December 1165 by Antipope Paschal III (invalidated) |

| Major shrine | Aachen Cathedral, Aachen, Germany |

| Feast | 28 January |

| Attributes | Crown Sword |

| Controversy | Canonization by an Antipope, not officially recognized as a Saint |

Emperor Otto III attempted to have Charlemagne canonized as a saint in 1000.[237] In 1165, Frederick Barbossa convinced the Antipope Paschal III to elevate him to sainthood.[237] As Paschal's acts were not considered valid, Charlemagne was not recognized as a saint by the Holy See in Rome.[238] He is not enumerated among the 28 saints named "Charles" in the Roman Martyrology.[239] Despite this lack of recognition, Charlemagne's cult became observed in Aachen, Reims, Frankfurt am Main, Zurich, and Regensburg, and he has been venerated in France since the reign of Charles V.[240] Pope Benedict XIV recognized his cult, beatifying him, in the eighteenth century[241] Benedict also quoted Charlemagne's capitularies in his apostolic constitution 'Providas' against freemasonry: "For in no way are we able to understand how they can be faithful to us, who have shown themselves unfaithful to God and disobedient to their Priests".[242]

Notes

- 1 2 Alternative birth years for Charlemagne include 742 and 747. There has been scholarly debate over this topic, see Birth and early life. For full treatment of the debate, see Nelson 2019, pp. 28–29. See further Karl Ferdinand Werner, Das Geburtsdatum Karls des Großen, in Francia 1, 1973, pp. 115–57 (online Archived 17 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine);

Matthias Becher: Neue Überlegungen zum Geburtsdatum Karls des Großen, in: Francia 19/1, 1992, pp. 37–60 (online Archived 17 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine) - ↑

- Old High German: Karlus

- Old French: Karlo

- Latin: Carolus

- English: Charles the Great[1]

- ↑ Monk and early chronicler Notker asserts that Leo only turned to Charlemagne after an appeal to Contantinople, which was refused.[106] Notker, however records the emperor's name as Micheal despite Irene reigning at the time (three Micheals reigned later in the 9th century). This may cast doubt on whether an appeal to Constantinople actually occurred. Paul Halsall remarks that Notker "handles events of the most general notoriety in a spirit completely independent of historical accuracy."[107]

- ↑ German: Zweikaiserproblem, "two-emperors problem"

- ↑ Latin: Karolus serenissimus augustus a deo coronatus magnus pacificus imperator Romanum gubernans imperium, qui et per misercordiam dei rex francorum atque langobardorum

- ↑ Latin: Carolus gratia dei rex francorum et langobardorum ac patricius Romanorum

- ↑ The nature of Himiltrude's relationship to Charlemagne is a matter of dispute. Charlemagne's biographer Einhard calls her a "concubine"[195] and Paulus Diaconus speaks of Pippin's birth "before legal marriage", A letter by Pope Stephen III seemingly referring to Charlemagne and his brother Carloman as being already married (to Himiltrude and Gerberga), and advising them not to dismiss their wives has led many historians to believe that Himiltrude and Charlemagne were legally married. However, the words employed by the pope could also mean that there had only been a promise of marriage. The acts of Saint Adalard of Corbie supports this hypothesis, for the monastic vocation of that Saint is described as due to the scruple he had regarding Charlemagne's dismissal of Princess Desiderata of the Lombards which occurred before any consummation of the marriage and possibly before any religious ceremony. (It is unclear whether the marriage ever took place or if Desiderata only received the homage of the nobility in accordance with her planned future position of Queen of the Franks.) If Saint Adalard was scandalised by this dismissal, it is highly unlikely he would have been unfazed about Himiltrude's dismissal, had she truly been married to Charlemagne.[196] Historians have interpreted the information in different ways. Some, such as Pierre Riché, follow Einhard in describing Himiltrude as a concubine.[197] Others, Dieter Hägemann for example, consider Himiltrude a wife in the full sense. Still others subscribe to the idea that the relationship between the two was "something more than concubinage, less than marriage" and describe it as a Friedelehe, a supposed form of marriage unrecognized by the Church and easily dissolvable. This form of relationship is often seen in a conflict between Christian marriage and more flexible Germanic concepts.

- ↑ From 781 Adrian began dating papal documents by the years of Charlemagne's reign, instead of the reign of the Byzantine Emperor.[199]

- ↑ It was during this visit to Rome that Charlemagne met Alcuin of York and invited him to join his court.[200]

- ↑ Through Beatrice of Vermandois, great-great granddaughter of Pepin of Italy and grandmother of Hugh Capet.[217][218]

- ↑ Through Hedwiga, great-great granddaughter of Louis the Pious and mother of Henry the Fowler.[219]

- ↑ Through Albert II, Count of Namur, great-grandson of Louis IV of France and great-great grandfather of Henry the Blind.[220][221]

- ↑ Berengar II of Italy was a great-great-great grandson of Louis the Pious.[222]

- ↑ Radbot of Klettgau, the founder of the House of Habsburg, married Ida of Lorraine, who descended from Charlemagne through both of her parents; from Cunigunda of France on her father's side and through the Capetians on her mother's side.

References

Citations

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 2.

- 1 2 McKitterick 2008, p. 116.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 2,68.

- ↑ Barbero 2004, p. 413.

- ↑ Fried 2016, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Anderson, Perry (2013). Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism. Verso Books. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-78168-008-7.

- ↑ Anderson, P.M. (1967). "The etymology of 'king' in Soviet Turkic languages". Canadian Journal of Linguistics. 13 (1): 34–36. doi:10.1017/S0008413100023185. S2CID 149378271.

- ↑ Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 270, 274–75.

- ↑ Collins 1999, pp. 161–72.

- ↑ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 35.

- ↑ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 37.

- 1 2 Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 38.

- ↑ Frassetto 2003, p. 292.

- ↑ Frassetto 2003, p. 292–93.

- ↑ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 271.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 65.

- ↑ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 McKitterick 2008, p. 71.

- ↑ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 Nelson 2019, p. 29.

- 1 2 Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 56.

- ↑ Fried 2016, p. 15.

- ↑ Collins 1999, p. 32.

- ↑ Barbero 2004, p. 11.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 28-28.

- ↑ (Nelson 2019, p. 15) "At 747 the scribe had written: ‘Et ipso anno fuit natus Karolus rex ’ (‘and in that year,King Charles was born’)."

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 28.

- ↑ Barbero 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ Fried 2016, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Barbero 2004, pp. 12–.

- ↑ Northen Magill, Frank; Aves, Alison (1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The Middle Ages. Routledge. pp. 226–. ISBN 978-1-57958-041-4.

- 1 2 3 Nelson 2019, p. 68.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 73.

- 1 2 McKitterick 2008, p. 72.

- ↑ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 32.

- 1 2 Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 34.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 72-3.

- ↑ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 62.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 64.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 75.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 65.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 79.

- 1 2 McKitterick 2008, p. 80.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 80-81.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 81.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 82.

- ↑ Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 57.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 99.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 99, 101.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 100-101.

- 1 2 Nelson 2019, p. 101.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 84-85, 101.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 106.

- ↑ Nelson, Janet L. (2007). Courts, elites, and gendered power in the early Middle Ages Charlemagne and others. Ashgate. ISBN 9780754659334. OCLC 1039829293.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 104-106.

- 1 2 McKitterick 2008, p. 87.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 88.

- 1 2 Costambeys, Innes & MacLean 2011, p. 66.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 109-110.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 89.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, p. 110-111.

- ↑ Kohn, George C. (2006). Dictionary of Wars. Infobase Publishing. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-1-4381-2916-7.

- 1 2 3 Einhard 1880, ch. 6. Lombard War.

- ↑ Einhard (1912–1913). "Einhard: The Wars of Charlemagne, c. 770–814". In William Stearns Davis (ed.). Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources, 2 Vols. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. pp. 373–375 – via Medieval Sourcebook, Fordham University.

- 1 2 Sullivan, Richard E.; et al. (2023). "Charlemagne". Britannica. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ↑ Hodgkin 1889, p. 69.