Karoly Grosz | |

|---|---|

_by_Karoly_Grosz_-_detail_from_teaser_poster.jpg.webp) Poster illustration of Boris Karloff as the monster from Frankenstein (1931) | |

| Born | Grósz Károly[note 1] March 9, 1897 Hungary[note 2] |

| Died | May 14, 1952 (aged 55) |

| Other names | Carl (or Karl) Grosz |

| Occupation(s) | Illustrator of film posters, advertising art director for Universal Pictures |

| Years active | c. 1920–1938 |

| Spouse |

Bertha Grosz (m. 1917) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

| |

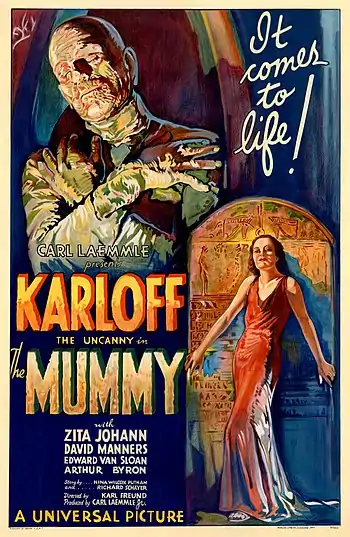

Karoly Grosz (US: /ˈkɑːˌrɔɪ ˈɡroʊs/, KAH-roy GROHSS; Hungarian: [ˈkaːroj ˈɡroːs]; March 9, 1897 – May 14, 1952) was a Hungarian–American illustrator of Classical Hollywood–era film posters. As art director at Universal Pictures for the bulk of the 1930s, Grosz oversaw the company's advertising campaigns and contributed hundreds of his own illustrations. He is especially recognized for his dramatic, colorful posters for classic horror films. Grosz's best-known posters advertised early Universal Classic Monsters films such as Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), and Bride of Frankenstein (1935). Beyond the horror genre, his other notable designs include posters for the epic war film All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and the screwball comedy My Man Godfrey (1936).

Original lithograph copies of his poster art are scarce and highly valued by collectors. Two posters illustrated by Grosz—ads for Frankenstein and The Mummy, respectively—have set the auction record for the world's most expensive film poster. The latter held the record for nearly 20 years and, at the time of its sale in 1997, it may have been the most expensive art print of any kind, including other forms of commercial art as well as fine art. The reference website LearnAboutMoviePosters (LAMP) noted that, as of August 2016, Grosz appeared more than any other artist on its comprehensive list of vintage film posters sold for at least $20,000.[3]

Despite the growth in his artwork's valuation and prominence, very little biographical information about Grosz is known. He was born in Hungary around 1896, immigrated to the United States in 1901, became a naturalized American citizen, lived in New York, and worked in film advertising between approximately 1920 and 1938. Only a small portion of his artistic output has been attributed to him, reflecting the standard anonymity of early American film poster artists.

Life and work

Personal life

Little is known about Grosz's life, as is the case with many early poster artists. Details of his biography have remained obscure even after his illustrations became some of the most valuable in film poster collecting.[3]

In an appendix of the 1988 book Reel Art providing biographical blurbs of poster artists, Grosz's birthplace was given as Hungary but his dates of birth and death were listed as unknown.[2] According to New York state and federal census records dated 1925 and 1930, Grosz was born in Hungary around 1896, immigrated to the United States in 1901, was a naturalized citizen, and spoke Yiddish. He was married to Bertha Grosz around 1917 and they had two children by 1930.[4]

He was sometimes referred to as "Carl" or "Karl" Grosz.[5] He legally changed his name to Carl Grosz Karoly in August 1937.[6]

Early career

.jpg.webp)

Grosz began working in film advertising as early as 1920, when an industry newspaper described him as an employee of producer Lewis J. Selznick's Selznick Pictures, working on art titling at the company's studios in Fort Lee, New Jersey.[8] In 1921, he was listed as a member of the New York-based professional organization Associated Motion Picture Advertisers and an employee of Associated Producers.[9] By 1923, he managed the advertising art departments of both Preferred Pictures and producer Al Lichtman's company.[10]

As a painter, Grosz tended to work with oil and watercolor,[11] and was influenced by a range of movements spanning Expressionism to Art Deco.[12] His posters for the 1923 silent film April Showers were considered novel for the time because the designs emphasized an "idea" or visual theme, rather than literal depictions of scenes that a viewer could expect to see in the film.[13] He was credited the same year with a billboard-size display for silent western The Virginian, the second adaptation of Owen Wister's 1902 novel of the same name.[14]

Career at Universal Pictures

Grosz began working at Universal's art department in New York in the mid-1920s. By 1930, he and Philip Cochrane had been appointed advertising art directors by the company's first advertising manager (and Philip's brother), Robert Cochrane.[15] Grosz and Cochrane have been credited with the generally high artistic quality of Universal's advertising throughout the 1930s.[16] Images like Grosz's teaser poster for Frankenstein introduced the general public to the now-familiar characters from Universal's early horror films.[17] Alongside horror-themed artwork, Grosz's tenure at Universal was distinguished by "lively, dramatic poster work to match the prestige and earnings" of such films as the World War I epic All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and the early screwball comedy My Man Godfrey (1936).[15]

Grosz's poster designs were exported to international markets, sometimes with modifications or variations.[18] In the United Kingdom, his posters for horror films were deemed so outrageous and lurid that by 1932 the British Board of Film Censors introduced stricter content regulations for advertising displays in public places.[19]

Grosz also made contributions to the look of Universal's films themselves. Most notably, his concept art for Frankenstein's monster, which suggested a more mechanical or robotic appearance, served as the source for the steel bolts in the monster's neck.[20] A comparatively minor detail, the neck-bolts are now an iconic visual element that is closely associated with the monster, especially Universal's version.[21] Although make-up artist Jack Pierce took credit in interviews for the monster's neck-bolts, Argentine-Canadian film critic and historian Alberto Manguel rejected Pierce's claim, finding that Grosz's concept art came earlier.[note 3]

Cochrane left Universal in 1937, while Grosz may have continued to work there as late as 1938.[23] Following their departures, Universal's poster art of the late 1930s and early 1940s entered a decline marked by a shift from vivid illustrations to mundane photographic reproductions. The quality of Universal's poster art improved again after Maurice Kallis was recruited from Paramount Pictures to serve as art director.[24]

List of attributed film posters and other art

Grosz is believed to have contributed hundreds of illustrations to Universal between the late 1920s and late 1930s.[25] He is often credited, at least partially, for the majority of Universal's posters produced while he was head of the art department—even for posters he may not have necessarily illustrated himself—because his position imputed responsibility for the overall art direction of the distributor's ad campaigns.[26] Determining the authorship of vintage film posters is intrinsically difficult, however, due to the generally anonymous nature of the work, especially in the United States.[27] Grosz's window card for Murders in the Rue Morgue is a rare example of an American film poster from the period signed by the artist.[28]

.jpg.webp)

The list below includes films with poster illustrations, ad campaign art direction, or other artwork that has been specifically attributed to Grosz in a secondary source. The gallery below includes individual designs attributed to him.

| Date | Film title | Studio | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Premiere or release | |||

| 1923 | Sep 30, 1923 | The Virginian | Preferred Pictures | [14] |

| Dec 10, 1923 | April Showers | [7] | ||

| 1927 | Nov 4, 1927 | Uncle Tom's Cabin[note 4] | Universal Pictures | [30] |

| 1930 | Apr 21, 1930 | All Quiet on the Western Front | [31] | |

| 1931 | Feb 14, 1931 | Dracula | [32] | |

| Nov 21, 1931 | Frankenstein | [33] | ||

| 1932 | Feb 21, 1932 | Murders in the Rue Morgue | [34] | |

| Oct 20, 1932 | The Old Dark House | [35] | ||

| Dec 22, 1932 | The Mummy | [36] | ||

| 1933 | Nov 13, 1933 | The Invisible Man | [37] | |

| Aug 1, 1933 | Moonlight and Pretzels | [15] | ||

| 1934 | May 7, 1934 | The Black Cat[note 5] | [38] | |

| 1935 | Apr 20, 1935 | Bride of Frankenstein | [39] | |

| Jul 8, 1935 | The Raven | [40] | ||

| 1936 | Jan 20, 1936 | The Invisible Ray | [41] | |

| Mar 9, 1936 | Love Before Breakfast | [42] | ||

| May 13, 1936 | Dracula's Daughter | [19] | ||

| Sep 6, 1936 | My Man Godfrey | [43] | ||

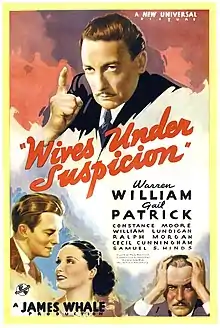

| 1938 | Jun 3, 1938 | Wives Under Suspicion | [2] | |

Gallery

_poster.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Dracula window card[44]

Dracula window card[44].jpg.webp)

Frankenstein, "Style A"[46]

Frankenstein, "Style A"[46].jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Murders in the Rue Morgue, window card[47]

Murders in the Rue Morgue, window card[47].jpeg.webp) The Old Dark House (1932)[35]

The Old Dark House (1932)[35]

.jpg.webp) The Mummy, three-sheet[48]

The Mummy, three-sheet[48].jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) The Invisible Man, "Style B"[49]

The Invisible Man, "Style B"[49].jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) The Invisible Ray (1936)[41]

The Invisible Ray (1936)[41].jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Dracula's Daughter (1936)[19]

Dracula's Daughter (1936)[19].jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Wives Under Suspicion (1938)[2]

Wives Under Suspicion (1938)[2]

Retrospective appraisal

Grosz's illustrations are now praised for their artistic quality and prized by collectors, but this was not the case until a half-century after the fact. In their own time, lithograph film posters were ephemeral objects to be distributed to movie theaters and disposed at the end of a film's run. Well-preserved original copies are scarce—for example, there were only two known copies of Grosz's one-sheet poster for The Mummy until 2001, when a third was found in a garage in Arizona.[52]

According to film historians Stephen Rebello and Richard C. Allen, Grosz's colorful, dramatic illustrations "brought ... a certain charm and almost naive perfection" to "the highly sensationalistic elements of directors Tod Browning's and James Whale's classics—hideous creatures, half-clad heroines, unsealed tombs, mad doctors."[53] In their estimation, Grosz's work in the horror genre was equaled only by William Rose's poster art for the 1940s B movies produced by Val Lewton for RKO Pictures, such as Cat People (1942).[53] British film historian Sim Branaghan wrote that Grosz's "wild imaginings" had an outsize influence on poster design in the UK from the 1950s onward, especially for the burgeoning market in exploitation films, as film censorship in the United Kingdom diminished and films with mature themes targeting adult audiences became more mainstream.[54]

Tony Nourmand and Graham Marsh wrote that Grosz's posters were highly original and often "as legendary as the films themselves."[37] Although his artistic style usually conformed to the relatively conservative standards of commercial art, they cited his teaser posters for Frankenstein and The Invisible Man as major exceptions that remain "striking," "avant-garde," and "ultra-modern" even by contemporary standards.[37] In 2013, Nourmand included the Frankenstein teaser in a book listing his choices for the 100 "essential" movie posters.[55] The American Film Institute included at least six posters illustrated by Grosz in its 2003 list of "100 Years... 100 American Movie Poster Classics": The Mummy (no. 4), The Invisible Man (no. 29), the teaser for Frankenstein (no. 40), the teaser for The Invisible Man (no. 69), Murders in the Rue Morgue (no. 85), and Dracula's Daughter (no. 88).[56] Premiere magazine ranked The Mummy poster at no. 15 in its 2007 list of the 25 best movie posters.[57]

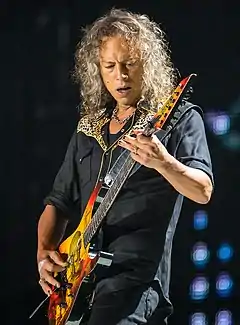

Kirk Hammett—the lead guitarist for Metallica and a prolific collector of horror memorabilia—named Grosz his favorite poster artist:

His lines are very seductive and there's a glamor and an elegance he manages to capture. In some of those movie posters, even though they're 'scary horror' movies, there's still a factor of beauty and elegance that draws me in even deeper. I think it's because of the fact it's not just horror. It's not just darkness and evil. There are also elements of beauty and hope in Grosz's illustrations. To me, he was a master.[38]

Hammett likened the Frankenstein teaser poster to an "Andy Warhol portrait gone evil" and, "in essence, an amazing example of pop art, 30 years before that term and movement even existed."[58] Since 1995, he has owned a custom ESP KH-2 electric guitar painted with a design from Grosz's Mummy three-sheet.[59]

Grosz's artwork has been exhibited in art museums. A one-sheet poster for The Mummy was featured in the 1999 exhibition "The American Century: Art and Culture 1900–2000" at the Whitney Museum of American Art.[60] A traveling exhibition of horror memorabilia from Hammett's collection, with several pieces by Grosz, debuted in 2017 at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts before continuing to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto and the Columbia Museum of Art in Columbia, South Carolina.[61] The high valuation of his work brought him posthumous recognition in his native Hungary as a noteworthy Hungarian artist who lived abroad.[62]

Valuation

The high-end art market generally excluded film memorabilia until the late 1980s.[65] Since that time, original copies of Grosz's poster designs have been highly valued at auction. As of 2012, six of the world's ten most expensive film posters had been produced for Universal horror films under his art direction.[66] He is also the best-represented artist on a much longer list maintained by the website LearnAboutMoviePosters (LAMP), which is periodically updated to include every known sale of a film poster for $20,000 or higher.[3]

Two posters illustrated by Grosz have set the record for most expensive film poster at auction. In an October 1993 auction, a Frankenstein poster sold at auction for $198,000 (equivalent to $401,000 in 2022), doubling the pre-sale estimation and nearly tripling the previous record price.[67] In March 1997, Sotheby's sold an original copy of the one-sheet for The Mummy for $453,000 (equivalent to $826,000 in 2022).[68] The sale exceeded not only Grosz's own previous record, but also the highest price then achieved for an Art Nouveau poster by French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec; as a result, The Mummy became not only the most-expensive poster in film advertising, but possibly in all of fine art.[69] While Grosz's name had been largely unknown before The Mummy sale, even among high-end collectors, other examples of his poster art dramatically increased in value shortly afterward.[70] Will Bennett of The Daily Telegraph said that "the name that collectors look for is Karoly Grosz", though he noted that the exceptionally high Mummy sale price, equivalent to "a decent painting by Gainsborough", "was regarded as a freak row between two collectors".[71]

The auction record held by The Mummy was broken in 2014 by a poster for the 1927 film London After Midnight.[63] An original Dracula lithograph set the record again in 2017 with a sales price of $525,800; while the illustrator was unidentified, Grosz was responsible for the art direction of the film's poster campaign as a whole.[72] In 2018, another copy of The Mummy poster was expected to reclaim the record with an estimated sales value as high as $1.5 million. It failed to sell, however, with no bid meeting the $950,000 minimum by the October 31 deadline.[73]

Notes

- ↑ Hungarian personal names follow Eastern name order: family name first, given name second. Both names are spelled with acute accents in the original Hungarian, but his name has been rendered without accent marks by almost all sources published during and after his career. At least one article, published in 2017, gave his name as "Károly Grósz".[1]

- ↑ Grosz was born in Hungary[2] Technically, this would have been the Hungarian region of the nation-state Austria-Hungary (1867–1918) at the time of his birth.

- ↑ Manguel found that Pierce had also claimed credit for other individual contributions to the appearance of Frankenstein's monster that were not his own; for example, Pierce similarly claimed that he had conceived the monster's flat-top boxy skull, even though the actual origin for the distinctive skull-shape was a description in the screenplay. Nevertheless, Manguel asserted Pierce was "in the end responsible" for the overall appearance and onscreen realization of the monster.[22]

- ↑ Grosz designed a souvenir book distributed at the film's premiere.[30]

- ↑ Hammett listed The Black Cat among Grosz's poster work but did not specify which of the film's multiple posters Grosz illustrated or designed.[38]

- 1 2 3 4 Grosz has been specifically credited for this poster's art direction, but not necessarily for its illustration.

Citations

- ↑ Siegel 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 325.

- 1 2 3 Poole & Poole 2016, p. 9 ("... it is even difficult to find information on the artist [who] has more movie posters [on LAMP's list of most-expensive posters] than any other—the big dollar leader—Karoly Grosz"). For the freely available version of LAMP's list, see Poole & Poole 2020a and Poole & Poole 2020b; note that this version of the list does not include artist attributions.

- ↑ Ancestry Library n.d.a (1925 New York state census); Ancestry Library n.d.b (1930 federal census).

- ↑ See, e.g., Spedon 1920, p. 40 and Dannenberg 1926, p. 110 ("Carl Grosz"); Gulick 1924, p. 29 ("Karl Grosz").

- ↑ Harman 1937, p. 15.

- 1 2 Grimm 1923, p. 342.

- ↑ Spedon 1920, p. 40.

- ↑ Dannenberg 1921, p. 177.

- ↑ Da Ponte 1923, p. 360 ("... Karoly Grosz, head of the Preferred Art Department"); Quigley 1923, p. 32 ("... Karoly Grosz as art manager" of "Al Lichtman Corporation").

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 325; Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 132.

- ↑ Branaghan & Chibnall 2006, p. 46; Heritage Auctions 2015.

- ↑ Grimm 1923, p. 342; Johnston 1923a, p. 1343; Johnston 1923b, p. 1462.

- 1 2 Da Ponte 1923, p. 360.

- 1 2 3 4 Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 93.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 93; Lieber 2011, p. 55; Jansen 2016, p. 45.

- ↑ Della Cava 2011; Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 133 (attributing the poster to Grosz).

- ↑ Branaghan & Chibnall 2006, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 Branaghan & Chibnall 2006, p. 47.

- 1 2 Skal 2001, pp. 132–133; Manguel 2003, p. 302.

- ↑ Skal 2001, pp. 132–133; Bailey 2011 (noting the neck-bolts are considered by Universal to be one of the copyright-protected elements of its iteration of Frankenstein's monster).

- ↑ Manguel 2003, p. 302.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, pp. 93, 215, 325.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 93; Lieber 2011, p. 55.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, pp. 93, 325.

- ↑ Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 132; Jansen 2016, p. 45.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 324; Walne 2012.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 325; Smith 2009, p. 266.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 224; Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 9.

- 1 2 Railton n.d.

- 1 2 Rebello & Allen 1988, pp. 276–277.

- 1 2 Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 217.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 218.

- 1 2 Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 179.

- 1 2 Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 220; Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 105.

- 1 2 Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 Hammett & Barkan 2017.

- ↑ Nourmand & Marsh 2004, pp. 9, 134.

- 1 2 Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 178; Tudor 2014

- 1 2 Nourmand & Marsh 2003b, p. 70.

- 1 2 Jansen 2016, p. 45.

- 1 2 Nourmand & Marsh 2003a, p. 8.

- ↑ Gregory 1998.

- ↑ Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 133.

- 1 2 Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 134.

- ↑ Smith 2009, p. 266.

- ↑ Burgess 2017.

- ↑ Nourmand & Marsh 2003b, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 224.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Jones 2002, p. 52.

- 1 2 Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 215.

- ↑ Branaghan & Chibnall 2006, p. 100.

- ↑ Nourmand 2013, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Dirks n.d. (providing general information about AFI's "100 American Movie Poster Classics" list); MovieGoods.com 2007a (entries 1–50 from AFI's list, including poster images); MovieGoods.com 2007b (entries 51–100); see gallery above for sources verifying attribution of these six posters to Grosz.

- ↑ Premiere 2007.

- ↑ Hammett & Chirazi 2012, p. 32.

- ↑ Scapelliti 2016 (providing the make and model of the guitar, ESP KH-2); Burgess 2017 (identifying the original poster design the guitar is based on, and attributing it to Grosz); Hammett et al. 2019, 3:50–3:56 (identifying 1995 as the specific year Hammett acquired the guitar).

- ↑ Sotheby's 2018.

- ↑ Barry 2019.

- ↑ Hamvay 2004; Jankó 2004.

- 1 2 Couch 2018.

- ↑ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 217 (crediting Grosz with the art direction of the Dracula poster campaign).

- ↑ LeDuff 1997.

- ↑ Pulver 2012.

- ↑ King 1993; Nourmand & Marsh 2003a, p. 10.

- ↑ Associated Press 1997; Feiertag et al. 2001, pp. 14, 50–51, 70, 125.

- ↑ Nourmand & Marsh 2003a, p. 6; Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 10.

- ↑ Windsor 1998.

- ↑ Bennett 1998, p. 19.

- ↑ Couch 2018; Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 217 (crediting Grosz with the art direction of the Dracula poster campaign).

- ↑ Michaud 2018.

Sources

Bibliography

- Branaghan, Sim; Chibnall, Stephen (2006). British Film Posters: An Illustrated History. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1-84457-221-8.

- Dannenberg, Joseph, ed. (1921). Wid's Year Book 1921–1922. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folks, Inc. – via the Internet Archive.

- Feiertag, Todd R.; Katz-Schwartz, Judith; King, Michael B.; Kuppig, Christopher J. (2001). Movie Collectibles. Woodinville, Washington: Martingale & Company. ISBN 1-56477-376-0 – via the Internet Archive (registration required).

- ———; Chirazi, Steffan (2012). Too Much Horror Business: The Kirk Hammett Collection. New York: Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-9659-5.

- Jones, Stephen (2002). "Introduction: Horror in 2001". In Jones, Stephen (ed.). The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror. Vol. 13 (1st US ed.). New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. pp. 1–81. ISBN 0-7867-1063-2 – via the Internet Archive (registration required).

- Lieber, Robert (2011) [1st pub. 2006]. Alcatraz: The Ultimate Movie Book (2nd printing ed.). San Francisco: Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. ISBN 978-1-883869-92-2 – via the Internet Archive (registration required).

- Manguel, Alberto (2003). "Bride of Frankenstein". In Buscombe, Edward; White, Rob (eds.). British Film Institute Film Classics. Vol. 1. London: British Film Institute and Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. pp. 297–317. ISBN 1-57958-328-8 – via Google Books.

- Nourmand, Tony (2013). 100 Movie Posters: The Essential Collection. London: Reel Art Press. ISBN 978-0-9572610-8-2.

- ———; Marsh, Graham, eds. (2003). Film Posters of the 30s: The Essential Movies of the Decade. London: Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 1-85410-938-3.

- ———; ———, eds. (2003). Science Fiction Poster Art. London: Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 1-85410-946-4.

- ———; ———, eds. (2004). Horror Poster Art. London: Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 1-84513-010-3.

- Rebello, Stephen; Allen, Richard C. (1988). Reel Art: Great Posters from the Golden Age of the Silver Screen. New York: Abbeville Pres. ISBN 0-89659-869-1.

- Skal, David J. (2001) [1st ed. pub. 1993 by W. W. Norton & Company]. The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror (Revised ed.). New York: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-19996-8 – via the Internet Archive (registration required).

- Smith, Grey (July 23, 2009). Heritage Auctions Vintage Movie Poster Auction Catalog #7008, Dallas, TX. Heritage Auctions. ISBN 978-1-59967-377-6 – via Google Books.

Periodicals and web sources

- Anon. (n.d.). "Karoly Grosz in the New York, State Census, 1925" – via Ancestry Library (subscription required).

- Anon. (n.d.). "Keroly [sic] Grosz in the 1930 United States Federal Census" – via Ancestry Library (subscription required).

- Anon. (March 2, 1997). "'Mummy' Costs $453,000". The New York Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017.

- Anon. (2007). "AFI Top 100 Movie Posters [# 1–# 50]". MovieGoods.com. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007.

- Anon. (2007). "AFI Top 100 Movie Posters [# 51–# 100]". MovieGoods.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 15, 2007.

- Anon. (July 25, 2015). "My Man Godfrey (Universal, 1936). One Sheet (27" × 41") Style C. | Lot #87029". HA.com. Heritage Auctions. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020.

- Anon. (2018). "The Mummy Film Poster | Single Lot". Sotheby's. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020.

- Bailey, Jonathan (October 24, 2011). "How Universal Re-Copyrighted Frankenstein's Monster". Plagiarism Today. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020.

- Barry, Rebecca Rego (July 16, 2019). "Metallica Guitarist's Horror and Sci-Fi Posters on View". Fine Books & Collections. Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019.

- Bennett, Will (September 21, 1998). "Object of the week". The Daily Telegraph. No. 44559. p. 19.

- Burgess, Anika (August 4, 2017). "Peer Into the Horror That Is Kirk Hammett's Movie Poster Collection". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019.

- Couch, Aaron (October 11, 2018). "Could Rare 'Mummy' Poster Fetch $1 Million at Auction?". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018.

- Da Ponte, T. S., ed. (September 22, 1923). "Preferred Display Is Attractive". News from the Producers. The Moving Picture World. New York: Chalmers Publishing Company. 64 (4): 360 – via the Internet Archive.

- Dannenberg, Joseph, ed. (February 28, 1926). "Greetings and Congratulations to Carl Laemmle from the Home Office Staff". The Film Daily. Vol. XXXV, no. 48. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folks, Inc. pp. 110–111 – via the Internet Archive.

- Della Cava, Marco R. (April 1, 2011). "Leisure: Emotion Pictures". Robb Report. Los Angeles: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020.

- Dirks, Tim (n.d.). "100 Greatest American Film Poster Classics". Filmsite.org. AMC Networks. Archived from the original on January 8, 2020.

- Gregory, Conal (October 24, 1998). "Answer the collect call". The Times. ProQuest 318010961 – via ProQuest (subscription required).

- Grimm, Ben H. (September 22, 1923). "With the Advertising Brains: A Weekly Discussion of the New, Unusual, and Novel in Promotion Aids". The Moving Picture World. New York: Chalmers Publishing Company. 64 (4): 340–342 – via the Internet Archive.

- Gulick, Paul, ed. (August 23, 1924). "Can You Solve This One?". Universal Weekly. Vol. 20, no. 2. New York: Motion Picture Weekly Co. p. 29 – via the Internet Archive.

- Hammett, Kirk (July 31, 2017). "Exclusive: Metallica's Kirk Hammett Talks Movie Posters, His New Book, and More!". Dread Central (Interview). Interviewed by Barkan, Jonathan. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019.

- ——— (July 31, 2017). "Kirk Hammett calls his legendary 'Greeny' Les Paul a 'guitar of the people'" (Interview). Interviewed by Shukla, Neil; Luis, Paul; Hebert, Mark. Cosmo Music. Retrieved March 3, 2020 – via YouTube.

- Hamvay, Péter (April 13, 2004). "A filmplakát aranykora" [The golden age of the film poster]. Népszava (in Hungarian). Budapest – via Arcanum Digitheca (subscription required).

- Harman, John N. (August 14, 1937). "Legal Notice". The Tablet. Brooklyn. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Hoffman, Jordan (October 15, 2018). "The Mummy: the story of the world's most expensive movie poster". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018.

- Jankó, Judit (April 18, 2004). "Mennyit ér az utca hírmondója?" [How much is a street messenger worth?]. Napi Gazdaság (in Hungarian). Budapest. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020.

- Jansen, Wim (October–November 2016). "Het koppie erbij houden" [Keeping a Clear Head]. Schokkend Nieuws (in Dutch and English). No. 122. p. 45. Archived from the original on June 28, 2017 – via Movie-Ink.com.

- Johnston, William A., ed. (September 15, 1923). "Teaser One-Sheet for 'April Showers'". Production–Distribution Activities. Motion Picture News. New York. 28 (11): 1343 – via the Internet Archive.

- ———, ed. (September 22, 1923). "'April Showers' Boasts Unusual Posters". Production–Distribution Activities. Motion Picture News. New York. 28 (12): 1462 – via the Internet Archive.

- King, Susan (October 19, 1993). "Movies – A Record". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020.

- LeDuff, Charlie (June 29, 1997). "Bird Made Him a Sleuth". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018.

- Luca, Dustin (August 16, 2017). "Kirk Hammett's favorite posters". The Salem News. CNHI. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020.

- Michaud, Chris (October 31, 2018). "'Mummy' film poster, expected to fetch record, fails to sell at auction". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 1, 2018.

- Poole, Ed; Poole, Susan (August 2016). "LAMP Post: Film Accessory News" (PDF). LearnAboutMoviePosters.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 31, 2017.

- ———; ———, eds. (March 2020). "LAMP Presents the Top Selling List: the most expensive movie posters on record". LearnAboutMoviePosters.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ———; ———, eds. (March 2020). "LAMP Presents the Top Selling List - Part 2: the most expensive movie posters on record". LearnAboutMoviePosters.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Premiere staff (March 2007). "The 25 Best Movie Posters Ever | 15. The Mummy". Premiere. New York: Hachette Filipacchi Media U.S. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Pulver, Andrew (March 14, 2012). "The 10 most expensive film posters – in pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020.

- Quigley, Martin J., ed. (May 19, 1923). "Jerome Beatty Heads Lichtman Advertising". Exhibitors Herald. Chicago: Quigley Publishing. 16 (21): 32 – via the Internet Archive.

- Railton, Stephen, ed. (n.d.). "Souvenir Program – Universal Pictures Corporation, New York: 1927". Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture. Charlottesville: University of Virginia. Archived from the original on April 30, 2017.

- Scapelliti, Christopher (October 11, 2016). "Kirk Hammett: Five Things We Learned from His Ernie Ball 'String Theory' Clip". Guitar World. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020.

- Siegel, Ed (August 17, 2017). "5 Things to Do This Weekend: A Metallica God and His Monster Collection to a Reimagined Joni Mitchell". The ARTery. Boston: WBUR-FM. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017.

- Spedon, Sam (November 6, 1920). "Keeping in Personal Touch". The Moving Picture World. Vol. 47, no. 1. New York: Chalmers Publishing Company. p. 40 – via the Internet Archive.

- Tudor, Lucia-Alexandra (Winter 2014). "Edgar Allan Poe on the Silver Screen". Romanian Journal of Artistic Creativity. 2 (4).

- Walne, Toby (February 26, 2012). "Poster Maker". Campden FB. London: Campden Wealth. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013.

- Windsor, John (August 15, 1998). "Personal finance: Film posters hit the big time". The Independent. Archived from the original on January 31, 2014.

.jpg.webp)

.jpeg.webp)

.jpg.webp)