A Kelvin bridge, also called a Kelvin double bridge and in some countries a Thomson bridge, is a measuring instrument used to measure unknown electrical resistors below 1 ohm. It is specifically designed to measure resistors that are constructed as four terminal resistors.

Background

Resistors above about 1 ohm in value can be measured using a variety of techniques, such as an ohmmeter or by using a Wheatstone bridge. In such resistors, the resistance of the connecting wires or terminals is negligible compared to the resistance value. For resistors of less than an ohm, the resistance of the connecting wires or terminals becomes significant, and conventional measurement techniques will include them in the result.

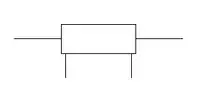

To overcome the problems of these undesirable resistances (known as 'parasitic resistance'), very low value resistors and particularly precision resistors and high current ammeter shunts are constructed as four terminal resistors. These resistances have a pair of current terminals and a pair of potential or voltage terminals. In use, a current is passed between the current terminals, but the volt drop across the resistor is measured at the potential terminals. The volt drop measured will be entirely due to the resistor itself as the parasitic resistance of the leads carrying the current to and from the resistor are not included in the potential circuit. To measure such resistances requires a bridge circuit designed to work with four terminal resistances. That bridge is the Kelvin bridge.[1]

Principle of operation

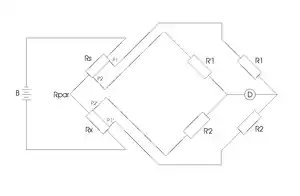

The operation of the Kelvin bridge is very similar to the Wheatstone bridge, but uses two additional resistors. Resistors R1 and R2 are connected to the outside potential terminals of the four terminal known or standard resistor Rs and the unknown resistor Rx (identified as P1 and P′1 in the diagram). The resistors Rs, Rx, R1 and R2 are essentially a Wheatstone bridge. In this arrangement, the parasitic resistance of the upper part of Rs and the lower part of Rx is outside of the potential measuring part of the bridge and therefore are not included in the measurement. However, the link between Rs and Rx (Rpar) is included in the potential measurement part of the circuit and therefore can affect the accuracy of the result. To overcome this, a second pair of resistors R′1 and R′2 form a second pair of arms of the bridge (hence 'double bridge') and are connected to the inner potential terminals of Rs and Rx (identified as P2 and P′2 in the diagram). The detector D is connected between the junction of R1 and R2 and the junction of R′1 and R′2.[2]

The balance equation of this bridge is given by the equation

In a practical bridge circuit, the ratio of R′1 to R′2 is arranged to be the same as the ratio of R1 to R2 (and in most designs, R1 = R′1 and R2 = R′2). As a result, the last term of the above equation becomes zero and the balance equation becomes

Rearranging to make Rx the subject

The parasitic resistance Rpar has been eliminated from the balance equation and its presence does not affect the measurement result. This equation is the same as for the functionally equivalent Wheatstone bridge.

In practical use the magnitude of the supply B, can be arranged to provide current through Rs and Rx at or close to the rated operating currents of the smaller rated resistor. This contributes to smaller errors in measurement. This current does not flow through the measuring bridge itself. This bridge can also be used to measure resistors of the more conventional two terminal design. The bridge potential connections are merely connected as close to the resistor terminals as possible. Any measurement will then exclude all circuit resistance not within the two potential connections.

Accuracy

The accuracy of measurements made using this bridge are dependent on a number of factors. The accuracy of the standard resistor (Rs) is of prime importance. Also of importance is how close the ratio of R1 to R2 is to the ratio of R′1 to R′2. As shown above, if the ratio is exactly the same, the error caused by the parasitic resistance (Rpar) is completely eliminated. In a practical bridge, the aim is to make this ratio as close as possible, but it is not possible to make it exactly the same. If the difference in ratio is small enough, then the last term of the balance equation above becomes small enough that it is negligible. Measurement accuracy is also increased by setting the current flowing through Rs and Rx to be as large as the rating of those resistors allows. This gives the greatest potential difference between the innermost potential connections (R2 and R′2) to those resistors and consequently sufficient voltage for the change in R′1 and R′2 to have its greatest effect.

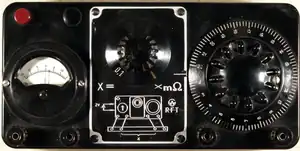

There are some commercial bridges reaching accuracies of better than 2% for resistance ranges from 1 microohm to 25 ohms. One such type is illustrated above. Modern digital meters exceed 0.25%.

Laboratory bridges are usually constructed with high accuracy variable resistors in the two potential arms of the bridge and achieve accuracies suitable for calibrating standard resistors. In such an application, the 'standard' resistor (Rs) will in reality be a sub-standard type (that is a resistor having an accuracy some 10 times better than the required accuracy of the standard resistor being calibrated). For such use, the error introduced by the mis-match of the ratio in the two potential arms would mean that the presence of the parasitic resistance Rpar could have a significant impact on the very high accuracy required. To minimise this problem, the current connections to the standard resistor (Rx); the sub-standard resistor (Rs) and the connection between them (Rpar) are designed to have as low a resistance as possible, and the connections both in the resistors and the bridge more resemble bus bars rather than wire.

Some ohmmeters include Kelvin bridges in order to obtain large measurement ranges. Instruments for measuring sub-ohm values are often referred to as low-resistance ohmmeters, milli-ohmmeters, micro-ohmmeters, etc.

References

- ↑ Northrup, Edwin F. (1912), "VI: The Measurement of Low Resistance", Methods of Measuring Electrical Resistance, McGraw-Hill, pp. 100–131, hdl:2027/mdp.39015067963275

- ↑ All About Circuits

Further reading

- Jones, Larry D.; Chin, A. Foster (1991), Electrical Instruments and Measurements, Prentice-Hall, ISBN 978-013248469-5

External links

Media related to Thomson bridge at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Thomson bridge at Wikimedia Commons- DC Metering Circuits chapter from Lessons In Electric Circuits Vol 1 DC and Lessons In Electric Circuits series.

- Discussion of 4 terminal measurement