Kevin McClory | |

|---|---|

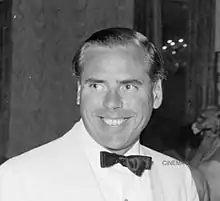

McClory in 1959 | |

| Born | 8 June 1924 |

| Died | 20 November 2006 (aged 82) |

| Occupation(s) | Screenwriter, film producer, film director |

| Website | www |

Kevin O'Donovan McClory (8 June 1924[1] – 20 November 2006) was an Irish screenwriter, film producer, and film director. McClory was best known for producing the James Bond film Thunderball and for his legal battles with the character's creator, Ian Fleming (later United Artists, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and Eon Productions).[2]

Early years

McClory was born in Dún Laoghaire, County Dublin, in 1924,[1] to noted actor Thomas John O'Donovan McClory (stage name Desmond O'Donovan) and Winifrede (née Doran), a writer, teacher and actress. He suffered from dyslexia. McClory's ancestry goes back to the famous Brontë family. Elinor McClory was the mother of Patrick Prunty who changed his name to Bronte when he emigrated from Ireland to England in 1802. Patrick was the father of Emily, Anne, Charlotte, and Branwell Brontë. McClory's parents were actors and theatre producers in Ireland.[3]

Second World War

As a teenaged radio officer in the British Merchant Navy, McClory endured attacks by German U-boats on two different occasions. The first attack occurred on 20 September 1942[4] while he was serving aboard The Mathilda. A U-Boat surfaced and attacked the ship with heavy machine gun fire. The crew of the ship fired back, and the U-Boat retreated. The second attack occurred on 21 February 1943 when McClory was serving on the Norwegian tanker Stigstad, which was attacked by multiple U-boats when it was a part of Convy ON 166. The ship sank, and McClory and the other survivors made it to a life raft. They survived in terrible conditions for two weeks and travelled more than 600 miles before being rescued off the coast of Ireland.[5] Two seaman died on the raft, and a third died soon after they were rescued. McClory suffered severe frostbite and lost the ability to speak for more than a year after the incident. When he recovered his voice, he was left with a pronounced stammer. He served out the rest of the war in Britain's Royal Navy.[6][7]

1950s

McClory started a career at Shepperton Studios in Middlesex as a film boom operator and location manager, where he worked on The Cockleshell Heroes for Warwick Films. He was an assistant to John Huston on films including The African Queen (1951) and Moulin Rouge (1952). He was an assistant director on Huston's version of Moby-Dick (1956), and associate producer and second-unit director on Mike Todd's Around the World in 80 Days (also 1956).

McClory was romantically involved with Elizabeth Taylor. Although he and Taylor reportedly had plans to marry, she eventually left him for her future husband Mike Todd. Todd and McClory fell out over Taylor, yet they managed to complete the final cut of the film side by side. The trio would eventually reconcile, and they remained friends until Todd's untimely death in 1958.[8][9]

In 1957, McClory led an expedition of 25 men in an attempt to drive around the world. He filmed a documentary of the adventure, One Road, as well as a series of ads for his sponsor Ford Motor Company. The team completed the journey in 104 days. He later wrote, produced and directed the 1957 film The Boy and the Bridge, with financial assistance from heiress Josephine Hartford Bryce (sister of Huntington Hartford) and her husband Ivor Bryce, a friend of Ian Fleming.[10]

1960s

In 1958 Fleming approached McClory to produce the first Bond film. McClory rejected all of Fleming's books but felt that the character James Bond could be adapted for the screen. McClory, Bryce, Fleming and Jack Whittingham developed the character through a number of treatments and screenplays. McClory, Fleming and Bryce settled on a screenplay, Longitude 78 West (later renamed Thunderball), and went into pre-production. Fleming novelised the draft screenplay as his ninth novel,Thunderball, in 1961 and initially did not credit McClory or Whittingham. McClory and Whittingham engaged libel lawyer Peter Carter-Ruck and sued Fleming shortly after the 1961 publication of the Thunderball novel, claiming he based it upon the screenplay the trio had earlier written.[11][12]

The trial opened in the High Court in London on 20 November 1963. After nine days, the case was settled out of court. Fleming paid McClory damages of £35,000 and McClory's court costs of £52,000, and future versions of the novel were credited as "based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham, and Ian Fleming" – in that order. Fleming conveyed to McClory the worldwide film rights to the novel Thunderball and McClory retained certain screen rights to the novel's story, plot, and characters. Harry Saltzman's and Albert R. Broccoli's production company Eon Productions later made a deal with McClory for Thunderball to be made into a film in 1965, with McClory producing.[2] Under the deal, Eon licensed McClory's rights for a period of ten years and in return they assigned to McClory any rights they had in the scripts and treatments. McClory made an uncredited cameo in the film.[13] By then, Bond was a box-office success, and series producers Broccoli and Saltzman feared a rival McClory film beyond their control; they agreed to McClory's producer's credit of a cinematic Thunderball, with them as executive producers.[14]

In 1968 McClory announced plans to make a film about Irish revolutionary leader Michael Collins, to star Richard Harris. The film was to have been shot at Ardmore Studios in 1969 but was never made.

1970s–1980s

In 1975, McClory and Richard Harris took out a full-page ad in The Nassau Tribune "demanding an end to internment without trial" in Northern Ireland. Conservative opposition leader Edward Heath who was visiting Nassau at the time called a press conference and advised "Harris and McClory to 'ask their friends to stop murdering people.'"

In 1976, McClory announced he was to produce a second adaptation of Thunderball, to be titled either Warhead, Warhead 8,[2] or James Bond of the Secret Service.[15] The script ran into difficulties, after accusations from Danjaq and United Artists that the project had gone beyond copyright restrictions, which confined McClory to a film based only on the novel Thunderball; once again, the project was delayed.[15] The project returned to the original nuclear terrorism plot of the original Thunderball, in order to avoid another lawsuit from Danjaq, and after McClory saw Jimmy Carter mention the issue in a 1980 presidential debate with Ronald Reagan.[16] A final attempt by Fleming's trustees to block the film was made in the High Court in London in the spring of 1983, but this was thrown out by the court and the film, now titled Never Say Never Again, was permitted to proceed.[17] Lord Justices Waller, Fox and May affirmed McClory's right to make James Bond films and enjoined the plaintiffs from taking similar legal action against McClory in the future. McClory went on to license his rights to Jack Schwartzman.

In 1988, he attempted an animated TV cartoon in partnership with a Dutch company, James Bond vs. S.P.E.C.T.R.E., but this never came to fruition, and James Bond Jr. was created as EON's counterattack to the aborted McClory animated attempt.[18]

In 1989, McClory attempted to recycle the Warhead script again, retitling the project Atomic Warfare. He approached Pierce Brosnan who had missed out on the role of James Bond to Timothy Dalton due to his contract with NBC's Remington Steele.[19] The film was supposed to be mainly set in Australia.[20]

1990s–2000s

McClory subsequently continued attempts to make other adaptations of Thunderball, including Warhead 2000 A.D. which was to be made by Sony.[2] MGM/UA took legal action against Sony and McClory in the United States to prevent the film going into production. MGM/UA abandoned the claim after settling with Sony. His rights were untouched. In 2004, Sony acquired 20% of MGM; however, the production and authority over everything involving the film version of James Bond is controlled by Eon Productions (Albert R. Broccoli's production company) and its parent company Danjaq, LLC. In 1992, McClory had to license the rights to producer Albert S. Ruddy for a proposed James Bond television program, but EON Productions blocked it, ending any hopes of a Bond TV show.[21]

Prior to the settlement with MGM in 1999, Sony filed a lawsuit against MGM claiming McClory was the co-author of the cinematic 007 and was owed fees from Danjaq and MGM for all past films. This lawsuit was dismissed in 2000 on the ground that McClory had waited too long with his claims. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals later affirmed this decision in 2001.[2][22]

2010s

On 15 November 2013, MGM and Danjaq LLC announced they had acquired all rights and interests of McClory's estate. MGM, Danjaq, and the McClory estate issued a statement saying that they had brought to an "amicable conclusion the legal and business disputes that have arisen periodically for over 50 years."[23]

Personal life

McClory was married twice. He was survived by two sons and two daughters. His first wife was Frederica Ann "Bobo" Sigrist, daughter of Fred Sigrist. He later married Elizabeth O'Brien, daughter of the racehorse trainer Vincent O'Brien.[24] They lived at Baltyboys House in Blessington, County Wicklow.

Death

McClory died on 20 November 2006, aged 82, at St. Columcille's Hospital in the Dublin suburb of Loughlinstown, from a cerebral hemorrhage, four days after the British release of Casino Royale.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Kevin McClory death certificate". Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 J.C. Maçek III (5 October 2012). "The Non-Bonds: James Bond's Bitter, Decades-Long Battle... with James Bond". PopMatters.

- ↑ "news Page CFM". www.washingtoninternational.com. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011.

- ↑ "D/S Mathilda - Norwegian Merchant Fleet 1939-1945". Warsailors.com. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ↑ "Stigstad (Norwegian Motor tanker) - Ships hit by German U-boats during WWII". uboat.net. 21 February 1943. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ↑ "The Stigstad - UBoat.net". Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Keegan, Patricia E. "Kevin McClory: James Bond Screenwriter's Washington Connection". Washingtoninternational.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ↑ A Valuable Property: The Life Story Of Michael Todd by Michael Todd Jr and Susan McCarthy Todd.

- ↑ C. David Heymann. Liz: An Intimate Biography of Elizabeth Taylor

- ↑ Callan, Michael Feeney Sean Connery Random House, 31 Oct 2012

- ↑ Johnson, Ted (15 November 2013). "MGM, 'James Bond' Producer End Decades-Long War Over 007". Variety. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ↑ "McClory, Sony and Bond: A History Lesson". Universal Exports.net. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ↑ "Thunderball". Obsessional.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ↑ Cork, John. "Inside "Thunderball"". Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Archived from the original on 20 November 2005. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- 1 2 Chapman 2009, p. 184.

- ↑ "La Frenais, Ian (1936–) and Clement, Dick (1937–)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ↑ Chapman 2009, p. 185.

- ↑ "Films: The Nineties". www.liner-notes.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ "10 Negative Ways Kevin McClory Affected The 007 Franchise". MI6-HQ.com. 17 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑ "Gevonden in Delpher - Trouw". Trouw. 4 August 1989.

- ↑ "Whither James Bond?". www.for-your-eyes-only.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ "Universalexports.net" (PDF). Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ↑ "MI6-HQ.com". 15 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Kevin McClory at IMDb

Bibliography

- Chapman, James (2009). Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films. New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-515-9.